California’s Special Education Teacher Shortage

This study is part of a series of research briefs examining special education in California produced by Policy Analysis of California Education.

California is in the midst of a severe and deepening shortage of special education teachers—and it is not alone. The field of special education at large has long been plagued by persistent shortages of fully certified teachers, in large part due to a severe drop in teacher education enrollments and high attrition for special educators. As a result, students with disabilities who often have the greatest needs are frequently taught by the least qualified teachers.

To better understand the nature of the shortage in California, and what can be done about it, the Learning Policy Institute released California’s Special Education Teacher Shortage. The study is part of a series of research briefs examining special education in California produced by Policy Analysis of California Education.

LPI researchers analyzed publicly available data on teacher credentials from the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, data from the 2017 Teacher Education Program Capacity Survey, and information provided by a focus group of nine current special education teacher leaders. The report provides an update on the status of the shortage, examines possible sources, identifies key challenges for special education teachers, and offers potential policy solutions.

Research Findings

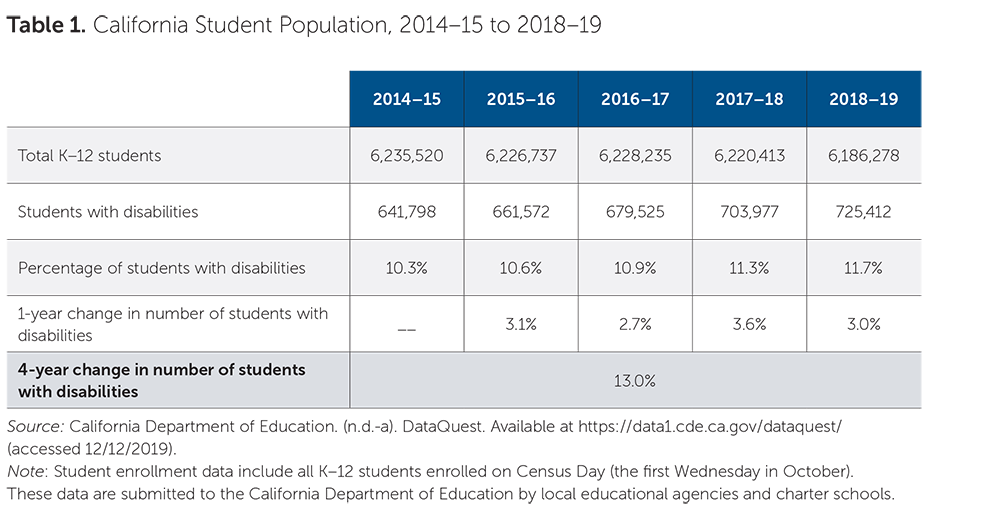

The report found that, in California, more than one out of five teachers in special education schools left their positions between 2015–16 and 2016–17 and about two of three teachers entering special education in the state hold a substandard permit or credential. Achievement rates for students with disabilities are alarmingly low: Statewide assessment scores for 2018–19 show that in math, only 13 percent of students with disabilities met or exceeded state standards, compared to 43 percent of students without disabilities; and in English language arts, only 16 percent of students with disabilities met or exceeded state standards, compared to 55 percent of students with no reported disability.

Attrition of special education teachers is associated with inadequate preparation and professional development, challenging working conditions that include large caseloads, overwhelming workload and compliance obligations, inadequate support, and compensation that is too low to mitigate high costs of living and student debt loads. Focus group participants confirm these conditions in California and their contribution to special educator attrition.

California districts report dealing with shortages by hiring long-term substitutes or underprepared teachers, allowing class sizes and caseloads to grow, or restricting the courses that are offered.

Since 2016, the state has been addressing teacher shortages by investing in several programs aimed at recruiting and retaining teachers. Among the most recent investments were one-time funds that established teacher residencies to recruit and train teachers in special education; a grant program to support “local solutions” for special education teacher recruitment and retention; and the Golden State Teacher Grant Program, which will provide one-time scholarships to students enrolled in teacher preparation programs (TPPs) and who commit to working in a high-need field at a priority school for four years after receiving their credentials. Because these investments were only recently made, they will take time to yield qualified teachers.

Loan forgiveness and service scholarship programs have proven to be highly effective in recruiting individuals into teaching and directing them to the neediest fields and have the potential to attract more teachers of color into special education. Other programs this study highlights include the now-defunct Assumption Program of Loans for Education loan forgiveness program and Governor’s Teaching Fellowship, which provided teacher candidates between $11,000 and $20,000 in exchange for a commitment to teach for at least four years in high-need schools and subjects. Beneficiaries of those programs were more likely to teach in low-performing schools and had higher retention rates than the state.

Policy Recommendations

Given the severity of the shortage and the multifaceted set of challenges that special educators face, resolving the shortage will require comprehensive, proactive policy solutions. Research suggests the following evidence-based approaches:

- Strengthen the pipeline into special education teaching with recruitment incentives for high-retention pathways. High-retention pathways into teaching—such as teacher residencies and grow-your-own programs that move paraprofessionals into teaching—have proven successful for recruiting and retaining diverse educators.

- Improve the quality of and access to preparation. As noted in this report, better prepared teachers are both more effective and more likely to stay in teaching. As California updates licensing expectations for special education teachers and works to increase the number of newly credentialed teachers, it will be important to build and expand the capacity of teacher education programs, as well as support new program designs that provide more intensive preparation and student teaching and ensure strong mentoring so that new teachers have the greatest possible chance for success.

- Expand and strengthen professional development. Studies show that intensive professional learning experiences are highly valued by special education teachers and associated with increased teacher efficacy and lower probability of attrition. The state can support the retention of current special education teachers by providing meaningful professional learning opportunities that help them meet the needs of students with disabilities, such as job-embedded coaching, mentoring, and ongoing support.

- Improve working conditions for special education teachers. Poor working conditions, including large caseloads and overwhelming responsibilities outside of instruction, may contribute to the attrition of special education teachers. California’s caseload caps are currently very high and are frequently waived, so that resource specialists, for example, can be responsible for 32 students or more, far above the levels of many other states. The state and districts can consider how to revise caseload expectations and provide additional administrative supports in order to help lighten workloads for special educators and ensure that they have the time needed to comply with federal and state requirements and to work effectively with students with disabilities.

The state and districts can also improve working conditions by supporting special education training for general education teachers and school and district leaders in order to improve their understanding of the needs of students with disabilities and their capacity to support these students and their special educator colleagues. This is particularly critical for ensuring that inclusion of students with disabilities in general education classrooms is done well and leads to improved student outcomes. - Increased compensation. National data suggest that adequate compensation can help districts retain special education teachers. In 2019, California increased state funding for special education and signaled an expectation for additional increases in 2020, which are reflected in the governor’s January 2020 budget. These investments can help relieve the fiscal pressure felt by districts, putting them in a better position to increase support for their special education teachers through higher salaries that recognize the costs of living, as well as their training and workload. Such investments can also support strategies like college loan repayment tied to retention and housing subsidies.

Conclusion

There are thousands of students with disabilities today in classrooms with teachers not equipped to provide them with the education they need—and are entitled to, under federal law—to live independently as adults, engage in learning opportunities beyond high school, and secure employment. Because the shortage emerges from a complex set of challenges, it will require comprehensive, proactive policy solutions that support not only teachers, but the kinds of programs that prepare them and the kinds of workplaces in which they can succeed in meeting the needs of some of the state’s most vulnerable students.

More action and sustained investments are needed to ensure a robust, well-prepared workforce of special education teachers now and into the future. Rather than filling more classrooms with underprepared teachers, California could invest in rapidly building the supply of qualified teachers to ensure that today’s students with disabilities do not have to wait for the kinds of educational supports and instruction they need to be successful.

California’s Special Education Teacher Shortage (report) by Naomi Ondrasek, Desiree Carver-Thomas, Caitlin Scott, and Linda Darling-Hammond is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not of our funders.