Does Teaching Experience Increase Teacher Effectiveness? A Review of the Research

Summary

To determine whether teachers, on average, improve in their effectiveness as they gain experience in the teaching profession, this brief summarizes the key findings from a critical review of the relevant research. A renewed look at this research is warranted due to advances in research methods and data systems that match student data with individual teachers, which have allowed researchers to more accurately answer this question.

Based on our review of 30 studies published within the last 15 years that meet rigorous methodological criteria in analyzing the effect of teaching experience on student outcomes in the United States, we find that:

- Teaching experience is positively associated with student achievement gains throughout a teacher’s career.

- As teachers gain experience, their students are more likely to do better on other measures of success beyond test scores, such as school attendance.

- Teachers make greater gains in their effectiveness when they teach in a supportive and collegial working environment, or accumulate experience in the same grade level, subject, or district.

- More experienced teachers confer benefits to their colleagues, their students, and to the school as a whole.

These conclusions suggest that policymakers should support policies and investments that (a) advance the ongoing development and professional growth of an experienced teaching workforce, and (b) increase the retention of experienced and effective teachers.

Introduction

A central value of public education in the 21st century holds that all children can learn. Yet this perspective has not necessarily carried over to social attitudes about teachers. While the research and policy communities agree that teachers improve quickly early in their careers,See, e.g., Matthew A. Kraft and John P. Papay, “Can Professional Environments in Schools Promote Teacher Development? Explaining Heterogeneity in Returns to Teaching Experience,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 36, no. 4 (2014): 476–500; Helen F. Ladd and Lucy C. Sorensen, “Returns to Teacher Experience: Student Achievement and Motivation in Middle School,” Education Finance and Policy (forthcoming); Douglas N. Harris and Tim R. Sass, “Teacher Training, Teacher Quality and Student Achievement,” Journal of Public Economics 95, no. 7–8 (2011): 798–812; Douglas O. Staiger and Jonah E. Rockoff, “Searching for Effective Teachers with Imperfect Information,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 24, no. 3 (2010): 97–118; Donald Boyd, Hamilton Lankford, Susanna Loeb, Jonah Rockoff, and James Wyckoff, “The Narrowing Gap in New York City Teacher Qualifications and Its Implications for Student Achievement in High-Poverty Schools,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 27, no. 3 (2008): 793–818. there is debate about whether teachers continue to learn after they gain significant experience in the classroom. That is, do teachers, on average, continue to improve in their effectiveness as they gain experience in the teaching profession?

The answer to this question has significant policy implications. For example, is it an equity problem that low-income students and students of color are more likely to be taught by the least experienced teachers and to attend schools with high rates of teacher turnover? Should we invest in professional development and learning opportunities for more experienced teachers, or focus these resources on novice teachers only? Should experience be rewarded through salary schedules that tie pay to experience in an effort to retain veteran teachers? Should policy be focused on building teaching as a long-term profession, or on recruiting and training a short-term teaching workforce?

This brief documents a review of research finding that, indeed, teachers do continue to improve in their effectiveness as they gain experience in the teaching profession. We find that teaching experience is, on average, positively associated with student achievement gains throughout a teacher’s career. Of course, variation in teacher effectiveness exists at every stage of the teaching career: not every inexperienced teacher is, on average, less effective, and not every experienced teacher is more effective.

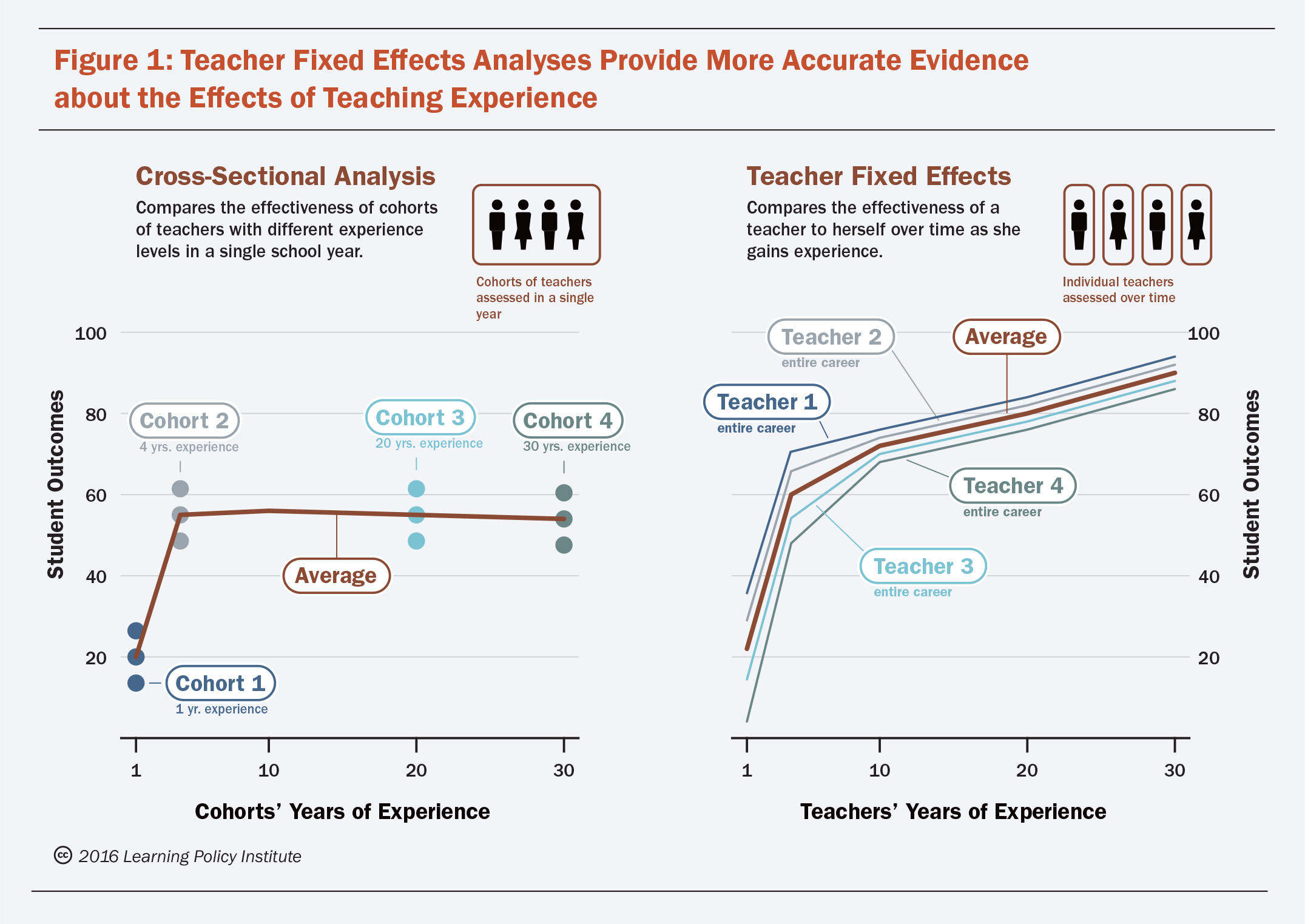

Some previous studies concluded that teachers plateau in their effectiveness early in their careers. Our findings are different for two major reasons. First, advances in data systems that can track teachers over time and match individual teachers to their students’ outcomes have allowed researchers to use a better research method, called “teacher fixed effects.” This method allows researchers to compare a teacher to herself over time as she gains more experience. In contrast, older studies often used less precise methods, such as cross-sectional analyses that use a “snapshot” approach to compare distinct cohorts of teachers with different experience levels during a single school year (see Figure 1).

Second, some studies limit the ranges of experience that they analyze. For example, some studies examine the benefits of teaching experience for only the first few years of a teacher’s career (e.g., years 0-5). Other studies group teachers into ranges of experience (e.g., years 0–4, 5–12, 13–20, 21–27). This can be problematic because it assumes that teacher productivity does not change within each of the ranges of experience.

The policy importance of this finding is heightened given the current context in which the teaching workforce has become less experienced.Richard M. Ingersoll, Lisa Merrill, and Daniel Stuckey, “Seven Trends: The Transformation of the Teaching Force” (Consortium for Policy Research in Education, 2014). The most recent national data suggest that compared to prior decades, a greater proportion of the teaching workforce has less than five years of experience.Ibid. In addition, this finding raises significant equity concerns because inexperienced teachers tend to be highly concentrated in underserved schools, where students need quality teachers most.Research finds that the least experienced teachers are disproportionately concentrated in low-income, high-minority schools, as well as schools serving large numbers of English learners. See, e.g., Julian R. Betts, Kim S. Reuben, and Anne Danenberg, Equal Resources, Equal Outcomes? The Distribution of School Resources and Student Achievement in California (San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California, 2000); Dan Goldhaber, Lesley Lavery, and Roddy Theobald, “Uneven Playing Field? Assessing the Teacher Quality Gap between Advantaged and Disadvantaged Students,” Educational Researcher 44, no. 5 (2015): 293–307; Boyd, et al., “The Narrowing Gap in New York City Teacher Qualifications and Its Implications for Student Achievement in High-Poverty Schools;” Tim R. Sass, et al., “Value Added of Teachers in High-Poverty Schools and Lower-Poverty Schools,” Journal of Urban Economics 72, no. 2–3 (2012): 104–22. For example, Black, Latino, American Indian, and Native-Alaskan students are three to four times more likely to attend schools with higher concentrations of first-year teachers than White students. English language learners also attend such schools at higher rates than native English speakers.U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, Civil Rights Data Collection Data Snapshot: Teacher Equity, (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, March 2014). In addition, students in the highest poverty schools are 50% more likely to have a teacher with less than four years of experience when compared to students in the lowest poverty schools.National Center for Education Statistics, SASS, Schools and Staffing Survey (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2012).

Our research does not indicate that the passage of time will make all teachers better or incompetent teachers effective. The benefits of teaching experience will be best realized when teachers are carefully selected and well prepared at their point of entry into the teaching workforce, as well as intensively mentored and rigorously evaluated prior to receiving tenure.Thomas J. Kane, Jonah E. Rockoff, and Douglas O. Staiger, “What Does Certification Tell Us about Teacher Effectiveness? Evidence from New York City,” Economics of Education Review 27, no. 6 (2008): 615–31. This will ensure that those who enter the professional tier of teaching have met a competency standard from which they can continue to expand their expertise throughout their careers.

Findings

We examined 30 studies that analyzed the effect of teaching experience on student outcomes in K–12 public schools in the United States, as measured by student standardized test scores and non-test metrics when available. We reviewed studies that examined teaching experience published in peer-reviewed journals and by organizations with established peer-review processes since 2003, when the use of teacher fixed effects methods became more prevalent. The studies represent diverse populations from different parts of the country, including California, Florida, Kentucky, New Jersey, New York, and North Carolina and include studies of both math and reading at the elementary-, middle-, and high-school levels. Our review led us to four findings.

1. Teaching experience is positively associated with student achievement gains throughout a teacher’s career. The gains from experience are highest in teachers’ initial years, but continue for teachers in the second and often third decades of their careers.

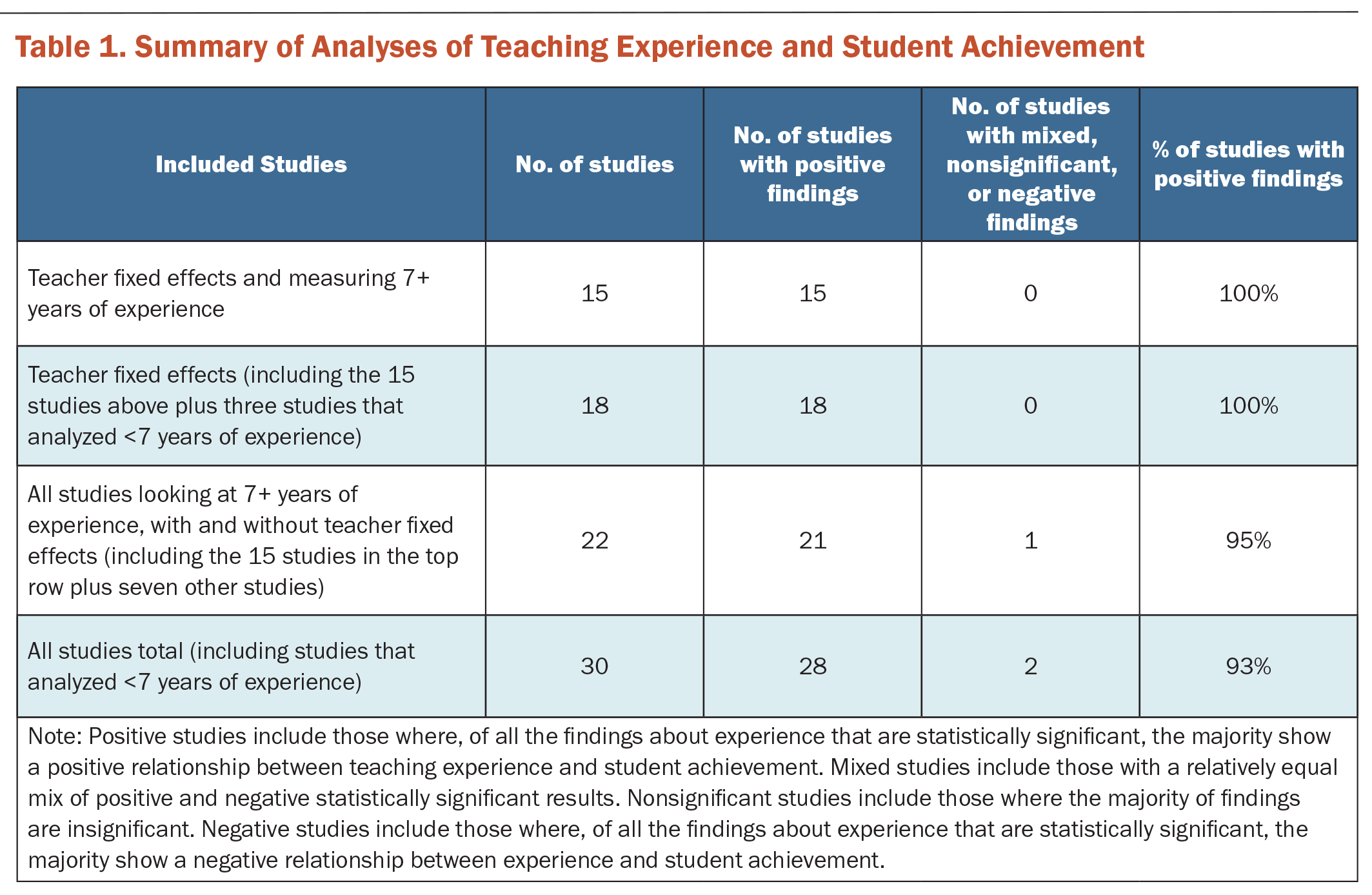

Studies generally have found that although teachers improve at greater rates during the first few years of their careers, teachers continue to improve, albeit at lesser rates, throughout their careers. In Table 1, we summarize the findings of the 30 studies we reviewed. Of these studies, 28 found that teaching experience is positively and significantly associated with teacher effectiveness.See Appendix of the full paper for a complete list of the studies. Nearly two-thirds of the studies analyze longitudinal datasets with teacher fixed effects, which is our preferred research method because it allows for the examination of whether a given teacher becomes more effective over time (see Figure 1). Among this body of research, all 18 studies found a positive and statistically significant relationship between teaching experience and student performance on standardized tests.

2. As teachers gain experience, their students are also more likely to do better on other measures of success beyond test scores, such as school attendance.

Researchers have recently begun to study whether more experienced teachers produce academic benefits for students that go beyond test scores. One study of 1.2 million middle school students in North Carolina analyzed student data on test scores as well as other noncognitive outcomes: absences, disciplinary offenses, amount of time students spent reading for pleasure, and amount of time students spent completing homework.Ladd and Sorensen, “Returns to Teacher Experience: Student Achievement and Motivation in Middle School.” The study controlled for a variety of characteristics, including race, eligibility for free and reduced-price lunch, and prior year achievement. Experienced teachers positively influenced several noncognitive outcomes. For example, being taught by English Language Arts (ELA) teachers with greater experience was associated with students spending more time reading for pleasure, and math teachers’ experience was associated with fewer disciplinary offenses.

One of the most striking findings was that as teachers gain experience, their students are less likely to miss school. This finding is important because of the strong evidence linking high rates of absenteeism with negative long-term educational outcomes.See, e.g., Robert Balfanz, Liza Herzog, and Douglas J. Mac Iver, “Preventing Student Disengagement and Keeping Students on the Graduation Path in Urban Middle-Grades Schools: Early Identification and Effective Interventions,” Educational Psychologist 42, no. 4 (2007): 223–35; Robert Balfanz and Vaughan Byrnes, “The Importance of Being There: A Report on Absenteeism in the Nation’s Public Schools” (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Center for Social Organization of Schools, 2012). Specifically, the North Carolina study found that one year of experience allowed an ELA teacher to reduce the proportion of students with high absenteeism by 2 percentage points, and that a teacher “who obtains over 21 years of experience on average reduces the incidence of high student absenteeism by 14.5 percentage points.”Ladd and Sorensen, “Returns to Teacher Experience: Student Achievement and Motivation in Middle School.” The study found similar effects for math teachers.

Importantly, more experienced teachers provided the greatest benefit to higher risk, chronically absent students. For example, ELA and math teachers with more than 21 years of experience reduced the number of students with over three absences by 6 and 4 percent, respectively, but reduced the number of students with over 17 absences by three times as much.Ibid.

3. Teachers make greater gains in their effectiveness when they teach in a supportive and collegial working environment, or accumulate experience in the same grade level, subject, or district.

Recently, research has begun to show that teachers’ rate of improvement over time also depends on the supportiveness of their professional working environment. In addition, a few studies have found that teachers with prior experience in the same grade level, subject area, or district show greater returns to experience than those with less relevant prior experience.Ben Ost, “How Do Teachers Improve? The Relative Importance of Specific and General Human Capital,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6, no. 2 (2014): 127–51; David Blazar, “Grade Assignments and the Teacher Pipeline: A Low-Cost Lever to Improve Student Achievement?,” Educational Researcher 44, no. 4 (2015): 213–27.

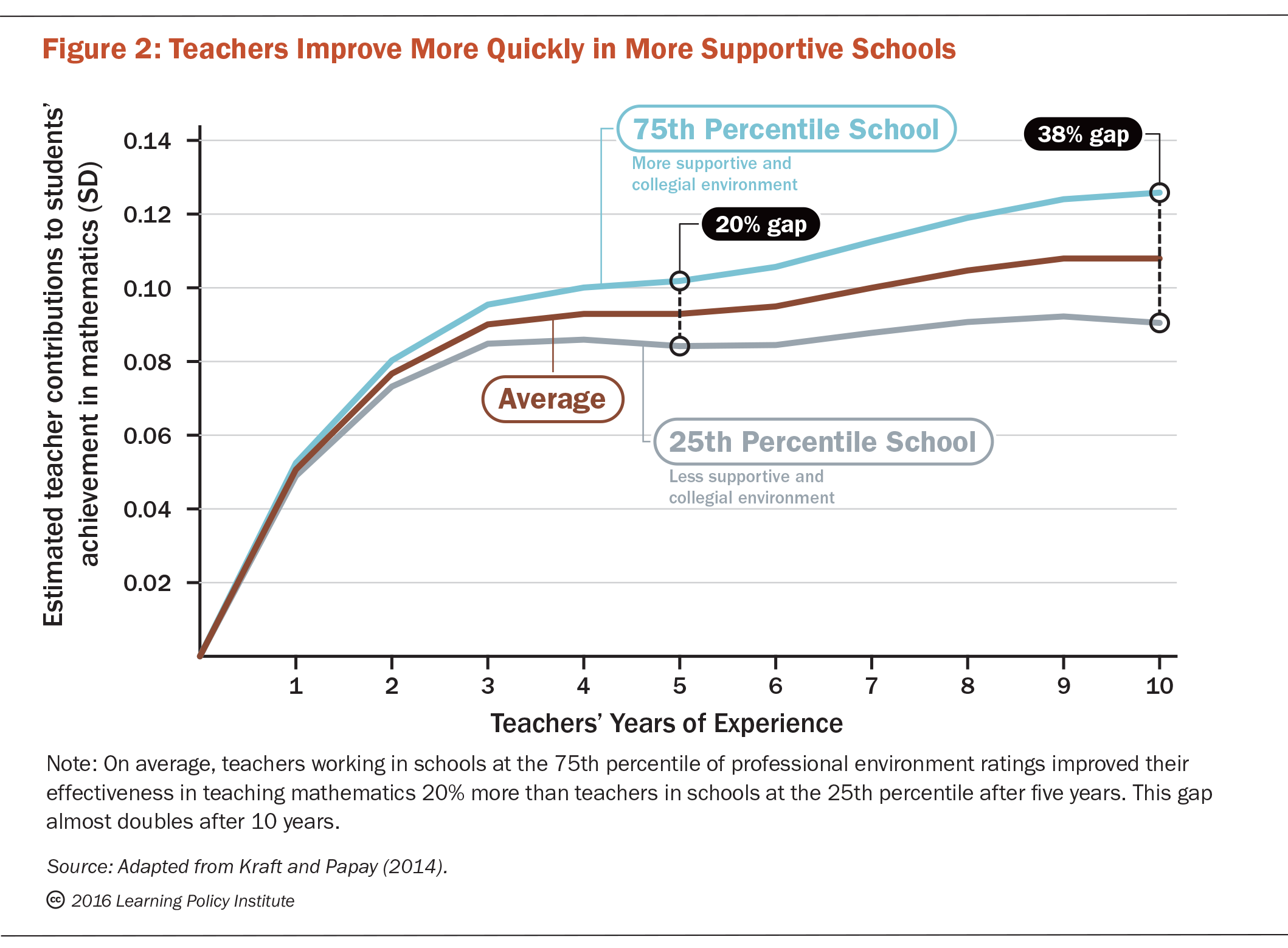

A recent large-scale study of math students over 10 years in North Carolina’s Charlotte-Mecklenberg School District examined how teachers’ improvement over time was related to their school environment.Kraft and Papay, “Can Professional Environments in Schools Promote Teacher Development? Explaining Heterogeneity in Returns to Teaching Experience,” 476–500. The study showed that teachers who work in schools with strong professional environments improve at faster rates than their peers working in schools with weaker professional environments. The study found that 10th-year teachers working in more supportive schools—characterized by a trusting, respectful, safe, and orderly environment, with collaboration among teachers, school leaders who support teachers, time and resources for teachers to improve their instructional abilities, and teacher evaluation that provides meaningful feedback—become substantially more effective than teachers working in schools that have few of the above characteristics (see Figure 2).

4. More experienced teachers confer benefits to their colleagues and to the school as a whole, as well as to their own students.

Research indicates that teachers whose colleagues are more experienced are more effective than those whose colleagues are less experienced.Kirabo C. Jackson and Elias Bruegmann, “Teaching Students and Teaching Each Other: The Importance of Peer Learning for Teachers,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1, no. 4 (2009): 85–108; Douglas N. Harris and Tim R. Sass, “Teacher Training, Teacher Quality and Student Achievement,” Journal of Public Economics 95, no. 7 (2011): 798–812. This suggests that more experienced teachers provide important additional benefits to their school community beyond increased learning for the students they teach. A study using data from third- through fifth-grade students and their teachers in North Carolina over an 11-year period found that teachers whose peer teachers had more experience tended to have improved student outcomes.Jackson and Bruegmann, “Teaching Students and Teaching Each Other: The Importance of Peer Learning for Teachers,” 85–108. The study also found that novice teachers benefit most from having more experienced colleagues. In addition, the study found that the quality of a teacher’s peers the year before, and even two years before, affected his or her current students’ achievement.

Policy Recommendations

These research findings show the benefits of more experienced teachers, on average, for both students and schools and suggest a number of implications for policymakers and educators at the federal, state, district, and school levels. Most importantly, policymakers should focus on program and investment strategies that build an experienced teaching workforce of high-quality individuals who are continually learning. Accomplishing this goal will require the implementation of policies and practices to increase teacher retention and reduce turnover in schools. We offer the following three recommendations:

1. Increase stability in teacher job assignments.

Teachers who have repeated experience teaching the same grade level or subject area improve more rapidly than those whose experience is in varied grade levels or subjects.See Ost, “How Do Teachers Improve? The Relative Importance of Specific and General Human Capital;” Blazar, “Grade Assignments and the Teacher Pipeline: A Low-Cost Lever to Improve Student Achievement?” Of course, many factors influence job assignment decisions, including teachers’ desires for professional growth and new challenges, as well as principals’ needs for flexibility in management.Ost, “How Do Teachers Improve? The Relative Importance of Specific and General Human Capital,” 127–151. School leaders, however, should be educated about the increased benefits of specific teaching experience and consider this in their decisions about teaching assignments.

2. Create conditions for strong collegial relationships among school staff and a positive and professional working environment.

Increasing opportunities for collaboration and for a more productive working environment is smart policy because of the promise this holds for increased teacher retention and because the benefits of experience are greater for teachers in strong professional working environments.Kraft and Papay, “Can Professional Environments in Schools Promote Teacher Development? Explaining Heterogeneity in Returns to Teaching Experience,” 476–500. Collegiality is hard to legislate, but there are nonetheless concrete steps that policymakers can take. District and school leaders can facilitate scheduling changes to allow for regular blocks of time for teachers who teach the same subject or who share groups of students to collaborate and plan curriculum together.Linda Darling-Hammond, The Flat World and Education: How America’s Commitment to Equity Will Determine Our Future (New York: Teachers College Press, 2010): 261. Federal and state policymakers can promote quality school leadership through the development of principal career pathways in which talented teachers are proactively recruited and intensively trained and coached by an expert principal.Darling-Hammond, The Flat World, 144; Linda Darling-Hammond, Debra Meyerson, Michelle LaPointe, and Margaret Terry Orr, Preparing Principals for a Changing World: Lessons from Effective School Leadership Programs, (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass: 2010).

3. Strengthen policies to encourage the equitable distribution of more experienced teachers, and discourage the concentration of novice teachers in high-need schools.

The new Every Student Succeeds Act requires states to develop plans describing how low-income students and students of color “are not served at disproportionate rates by ineffective, out-of-field, or inexperienced teachers” and to evaluate and publicly report on their progress in this area.Public Law 114-95, Every Student Succeeds Act, section 1111(g)(1)(B). Districts are required to “identify and address” teacher equity gaps.ESSA, section 1112(b)(2). As the U.S. Department of Education works to implement these provisions, much will depend on how the term “inexperienced teacher” is defined. The Department of Education should strengthen its enforcement of these provisions and define the term “inexperienced” teacher to include teachers who, at a minimum, are in their first or second year of teaching. Such a definition would be consistent with the definition used by the Department in its Civil Rights Data Collection, which provides important data on the concentration of first-year and second-year teachers in every school in the nation.See U.S. Department of Education, Civil Rights Data Collection, 2011-2012 Civil Rights Data Collection Definitions (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education, 2011–12), (defining “first year of teaching” and “second year of teaching”).

Other strategies for developing an experienced teaching workforce that is continually learning have been well documented elsewhere, such as providing clinically based preparation and high-quality mentoring for beginners, as well as career advancement opportunities for expert, experienced teachers.See John P. Papay, et al., “Does an Urban Teacher Residency Increase Student Achievement? Early Evidence from Boston,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 34, no. 4 (2012): 413–34; G. T. Henry, K. C. Bastian, and A. A. Smith, “Scholarships to Recruit the ‘Best and Brightest’ into Teaching: Who Is Recruited, Where Do They Teach, How Effective Are They, and How Long Do They Stay?,” Educational Researcher 41, no. 3 (2012): 83–92; Richard M. Ingersoll and Michael Strong, “The Impact of Induction and Mentoring Programs for Beginning Teachers: A Critical Review of the Research,” Review of Educational Research 81, no. 2 (2011): 201–33; LPI Paper, “Recruiting and Retaining Excellent Educators: Research, Policies and Strategies to Strengthen the Teaching Workforce,” Learning Policy Institute (forthcoming); LPI Paper “Teacher Residencies,” Learning Policy Institute (forthcoming). As documented here, our review of the latest research underscores that these investments can pay big dividends for our nation’s students.

External Reviewers

The full report upon which this research brief is based benefited from the insights and expertise of two external reviewers: Gene Glass, Regents’ Professor Emeritus from Arizona State University and Senior Researcher at the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado Boulder; and Helen Ladd, Susan B. King Professor of Public Policy Studies and Professor of Economics at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy. We thank them for the care and attention they gave the report. Any remaining shortcomings are our own.

Research Brief: Does Teaching Experience Increase Teacher Effectiveness? A Review of the Research by Tara Kini and Anne Podolsky is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Research in this area of work is funded in part by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Ford Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Sandler Foundation.