Op-Ed: How to Fix the Country’s Failing Schools. And How Not To.

This commentary was first published on January 9, 2016 in The New York Times.

A quarter-century ago, Newark and nearby Union City epitomized the failure of American urban school systems. Students, mostly poor minority and immigrant children, were performing abysmally. Graduation rates were low. Plagued by corruption and cronyism, both districts had a revolving door of superintendents. New Jersey officials threatened to take over Union City’s schools in 1989 but gave them a one-year reprieve instead. Six years later, state education officials, decrying the gross mismanagement of the Newark schools, seized control there.

In 2009, the political odd couple of Chris Christie, the Republican governor-elect, and Cory Booker, Newark’s charismatic mayor, joined forces, convinced that the Newark system could be reinvented in just five years, in part by closing underperforming schools, encouraging charter schools and weakening teacher tenure. In 2010 they persuaded Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s chief executive, to invest $100 million in their grand experiment. “We can flip a whole city!” the mayor enthused, “and create a national model.”

No one expected a national model out of Union City. Without the resources given to Newark, the school district there, led by a middle-level bureaucrat named Fred Carrigg, was confronted with two huge challenges: How could English learners, three-quarters of the students, become fluent in English? And how could youngsters, many of whom came from homes where books were rarities, be turned into adept readers?

Today Union City, which opted for homegrown gradualism, is regarded as a poster child for good urban education. Newark, despite huge infusions of money and outside talent, has struggled by comparison. In 2014, Union City’s graduation rate was 81 percent, exceeding the national average; Newark’s was 69 percent.

What explains this difference? The experience of Union City, as well as other districts, like Montgomery County, Md., and Long Beach, Calif., that have beaten the demographic odds, show that there’s no miracle cure for what ails public education. What business gurus label “continuous improvement,” and the rest of us call slow-and-steady, wins the race.

Slow-and-steady was anathema to Mr. Booker and Mr. Christie, who had big dreams for Newark. But as Dale Russakoff writes in her absorbing account “The Prize,” the politicians’ optimism proved misplaced. What went wrong had as much to do with their top-down approach as with the proposals themselves.

The mayor pledged to involve the public before making any decisions, but efforts at community engagement, orchestrated by out-of-town advisers, proved shambolic. The only recommendations that got traction — closing 11 public schools, opening charters and themed high schools — were advanced by consultants, who gobbled up more than $20 million in fees.

In 2011, Mr. Christie appointed 39-year-old Cami Anderson — a Teach for America alumna — superintendent. She introduced some solid ideas, like replacing the weakest performers with “renew schools” and persuading charters to enroll more poor kids. But she ran into trouble with parents when she did away with neighborhood schools and laid off hundreds of workers to pay for her initiatives.

Her hurry-up style made matters worse. “She didn’t listen,” contends Ms.Russakoff. “She said her plan — ‘16-dimensional chess’ — was too complex for parents.” After repeated heckling by teachers and parents, Ms. Anderson stopped attending board meetings.

One of Mr. Booker’s goals was to make Newark the nation’s “charter school capital,” and he largely succeeded. While these schools have recorded higher test scores and graduation rates than the traditional schools, money explains much of that gap. Freed from the district’s bureaucracy, the charters have nearly a third more dollars to spend on each student, $12,650 versus $9,604, which buys additional teachers, tutors and social workers.

The push to expand charters angers activists like Junius Williams, director of the Abbott Leadership Institute at Rutgers University. “Charters have drained resources necessary to teach most Newark students,” he told me.

In 1989, with one year to shape up Union City, Mr. Carrigg, with a cadre of teachers and administrators, devised a multi-pronged strategy: Focus on how kids learn best, how teachers teach most effectively and how parents can be engaged. Non-English speakers had previously been expected to acquire the language through the sink-or-swim method. So the district junked its old approach. Instead, English learners are initially taught in their own language, mainly Spanish, and then are gradually shifted to English. The system started hiring more teachers who spoke Spanish or had E.S.L. (English as a Second Language) training.

The bilingual approach went beyond the classroom. Even though many parents speak only Spanish, meetings had been conducted and written information prepared only in English. In the new era, bilingualism quickly became the norm. Parents, made to feel welcome in the schools, were conscripted to help with their children’s homework and reinforce the schools’ high expectations for them.

To get students excited about reading, the schools became word-soaked environments, with tons of reading and daily writing assignments linked even to subjects like art and science that traditionally don’t require as much writing.

The Union City reformers opted to focus initially on the youngest children, whose potential for improvement was greatest. When New Jersey began to fund preschool for poor urban districts in the late 1990s, the district seized on the opportunity to devise a state-of-the-art program that enrolled almost every 3- and 4-year-old in the community.

Teachers rethought skill-and-drill instruction, instead emphasizing hands-on learning and group projects. Help came, in the form of coaches — veteran teachers — working side by side with newbies and time set aside for teachers to collaborate. Students were frequently assessed, not to punish teachers but to pinpoint areas where help was needed.

Stable leadership proved essential. In the years preceding the state’s near-takeover, superintendents were hired and fired based on their politics; during the past quarter-century there have been just three superintendents, all of them products of the district. Nationwide, the average tenure of a city schools chief is only three years.

“The real story of Union City is that it didn’t fall back,” Mr. Carrigg told me. “It stabilized and has continued to improve.” Recent changes include the introduction of Mandarin Chinese from preschool on, a STEM-focused elementary school and a nursery for young parents in high school.

Newark’s big mistake was not so much that the school officials embraced one solution or another but that they placed their faith in the idea of disruptive change and charismatic leaders. Union City adopted the opposite approach, embracing the idea of gradual change and working within existing structures.

Newark is beginning to do the same. Since the appointment in 2015 of Christopher Cerf, formerly New Jersey’s education commissioner, as Newark’s superintendent, more attention is being paid to the positive side of the school district ledger. While charters remain controversial in Newark, Mr. Cerf emphasizes helping the public schools achieve similar results. “Charters are succeeding,” he told me, “because they have substantially more discretion. We need to level the playing field.”

Mr. Cerf and Raz Baraka, who succeeded Cory Booker as mayor, recently announced that up to $12.5 million of the Zuckerberg gift will be invested in a network of “community schools” — sunrise-to-sunset schools that offer health care and social services, located in the city’s most troubled neighborhoods.

“Mark Zuckerberg’s $100 million gift isn’t a lot of money in a district that spends $1 billion a year, but it sparked the conversation,” Dominique Lee, the executive director of Brick, which runs two Newark schools, told me. “People are angry now at what’s been going on, but it’s ‘good angry,’ not ‘bad angry,’ like before. They’re asking: ‘What do we need to do to save traditional public schools?’”

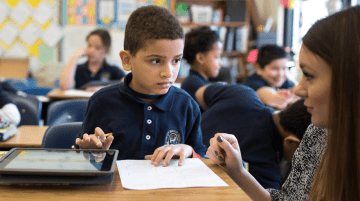

Photo: Karsten Moran/The New York Times/Redux