Accelerating Learning As We Build Back Better

This post was originally published on April 5, 2021 by Forbes, and is part of LPI's Learning in the Time of COVID-19 blog series, which explores strategies and investments to address the current crisis and build long-term systems capacity.

After a year of struggling with distance learning and hybrid models, parents, teachers, and policymakers across the country are concerned about “learning loss” and how to recover from the educational effects of the pandemic. While many of us resist the deficit orientation of learning loss language, these concerns are certainly legitimate: As the crisis began, millions of children, particularly those in low-income communities, lacked access to the computers and connectivity that would make in-person remote learning possible, creating even greater equity gaps than those that already existed.

Furthermore, many low-income communities and communities of color have been especially hard hit by COVID-19, with higher rates of infection, hospitalization and death, as well as greater rates of unemployment and housing and food insecurity. These traumatic events, coupled with the ongoing instances of police shootings of unarmed civilians, have led to a growing and ever more visible divide between the haves and the have-nots, with many students encountering barriers to keeping up in school and others disengaging from school altogether.

Why We Should Aim for Reinvention

It is critically important, though, that we address these concerns based not on outdated notions about remediation, but on what we now know about how people learn effectively. Among those lessons are the following:

- Positive relationships and attachments are the essential ingredient that catalyzes healthy development and learning … and enables resilience from trauma.

- Children actively construct knowledge by connecting what they know to what they are learning within their cultural contexts. Creating those connections is key to learning.

- Learning is social, emotional, and academic. Children learn best when they feel safe, affirmed, and deeply engaged within a supportive community of learners.

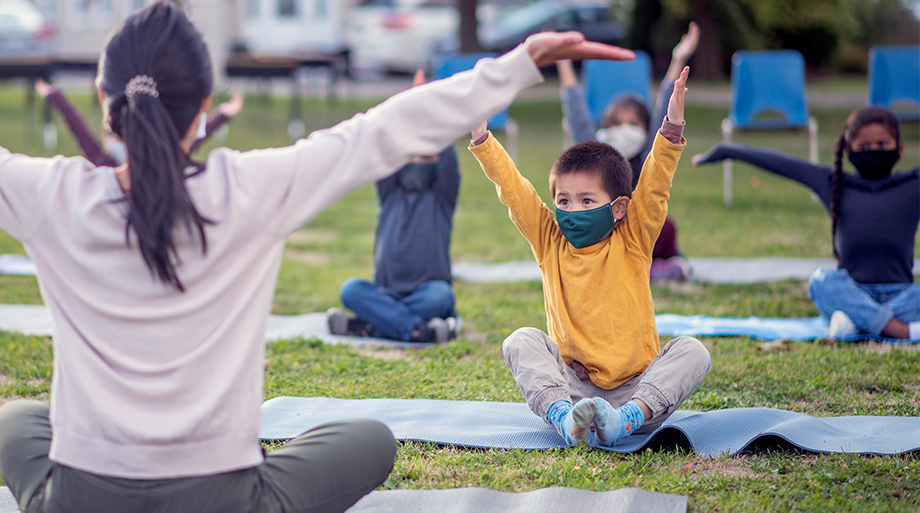

- Learning is enhanced by physical activity, joy, and opportunities for self-expression.

- Students’ perceptions of their own ability influence learning. All children are motivated to learn the next set of skills for which they are ready; few are motivated by labels that rank them against others or communicate stigma.

These principles — drawn from brain science and research about learning — mean that we must reinvent school in ways that center relationships (unlike the factory model designs we have inherited), allow educators to deeply understand what children know and have experienced so they can build on it and draw connections to new learning; lead with social and emotional supports and skills, fully integrated with academic learning; and enable children to see their strengths and what they do know — to feel competent and confident that they can learn. We also need to support educators in recognizing the effects of trauma, accessing resources for children, and supporting their attachment and healing, rather than unwittingly exacerbating the effects of trauma by using curriculum and rules that alienate, rather than reattach students to school.

As researchers at the Learning Policy Institute have noted in Restarting and Reinventing School, it’s important not to return to “normal” but to create a new normal that is grounded in what we know from the science of learning and development.

What a “New Normal” Should Look Like

If we really want to support learning, the return to school should not include these staple features of an outdated approach to learning that research has found actually undermine achievement:

- Testing students to label and track them into “high,” “average,” and “low” groups that are segregated by perceived ability — and often by race, class, and language background as well;

- Offering regimented drill and kill remedial instruction in these segregated groups, focused on filling gaps in basic skills in the artificial ways they are assessed on multiple choice tests, which then often causes them to be taught in equally artificial ways;

- “Personalizing” learning by putting students in front of programmed computers for machine-based instruction for long hours at a time — or piles of worksheets that offer the same decontextualized approach to learning;

- Punishing students who disengage or express frustration and despair by excluding them from the classroom or removing “privileges” like recess and library time;

- Placing the neediest students in remedial classes with the least trained and experienced teachers who are least likely to know how to create productive learning environments.

Instead, a supportive school return — both this summer and next fall — will seek to ensure that students:

- Experience warm relationships and social-emotional supports achieved by redesigning schools so that they are relationship-centered, with built-in time for creating community, trust, and belonging among students and with families;

- Engage in outdoor play and exercise, expressive arts, and collaborative activities that support brain development and learning;

- Encounter authentic, culturally responsive learning tasks and inquiry projects connected to their experiences that allow them to understand and positively impact their environment;

- Assess what students need both socially and emotionally as well as academically, address trauma with healing and support, and identify the next steps they are ready to take in their learning rather than labelling them;

- Accelerate learning through additional time and high-quality tutoring rather than tracking. Intensive tutoring, found to be highly effective, both establishes strong relationships and customizes teaching directly to student readiness and needs.

This work should start right away and continue into the summer and next year. Summer school should not be a boot camp designed for students who are “behind.” Instead, studies find the most effective models provide rich opportunities for play and enrichment paired with academic content offered through small classes and individualized instruction, like those Cajon Valley School District in California has structured in its “Camp Cajon” summer enrichment program.

Educators can partner with community-based organizations as Tulsa Public Schools plans to do this summer with partners ranging from the YMCA to Tulsa’s Bike Club, Global Gardens, Reading Partners, Debate League, and more, creating highly engaging opportunities that mix recreation with learning. They can also motivate and educate students with opportunities like the Children’s Defense Fund (CDF) Freedom Schools. Modeled after the 1963 Mississippi Freedom Schools that developed leaders in the black community, CDF Freedom Schools now partner with community organizations, churches, and schools to provide literacy-rich after school and summer programs for k–12 students in all kinds of communities. These programs, found to be effective in promoting reading gains, motivate and inspire students as they read books that are culturally meaningful and discuss ideas aimed at social action and civic engagement for the betterment of their communities.

The opportunity to contribute is highly motivating for students, and recovery from trauma can be enabled by engaging in projects that allow students to grow and improve things: from school or community gardens and murals that feed and beautify, to a range of school, classroom, or community improvement projects that show students their strengths and produce a sense of agency as they advance growth and well-being for themselves and others.

As in-person school resumes, schools can help teachers understand students’ needs with tools like the CORE districts’ RALLY survey that provides regular information about students’ experiences and wellness, as they integrate social and emotional learning, mindfulness, and wraparound supports health, mental health and social services. The more than $122 billion just allocated to k–12 schools in the American Rescue Plan Act provides states and districts with the opportunity to support all of these kinds of services and their coherent delivery through community schools models as a critical part of learning recovery, alongside academic investments.

To re-attach students to school and to accelerate learning throughout the coming year, the most effective classrooms will provide well-designed collaborative learning opportunities in non-tracked classrooms using curricula that involve students in engaging mathematical inquiries, culturally-affirming expeditions in English language arts, mind-opening experiments in science, and opportunities to reflect and express in the arts and humanities. And to ensure that students are able to recover successfully, these can be coupled in expanded learning time with small group supports and high-intensity tutoring that supports rapid skill development during and beyond the school day, and with successful strategies like the Acceleration Academies offered during winter and spring break weeks in Lawrence, Massachusetts. In these academies, excellent teachers work with students in small groups on hands-on learning that brings them back to school with strong skills and confidence.

If we focus only on “learning loss,” we will walk down a familiar road, one paved with repetitive remediation, disengaged students, and reluctant families who are disillusioned with impersonal, inauthentic learning. Beginning this summer and continuing into the next academic year, we should restructure schooling to build trust within supportive classrooms that do not ignore the trauma of the pandemic. We can create time to build capacity among trauma-informed educators, and we can make decisions based on multiple measures of student learning and well-being. If students feel attached and affirmed, and if they receive enriching experiences with targeted supports, they will learn in ways that far exceed the “old normal” and set the norm for a new age in education that builds on how children really learn, rather than working against it.