The Federal Role in Tackling Teacher Shortages

This is the third blog in a series exploring the state of teacher shortages during the COVID-19 pandemic and evidence-based solutions for addressing immediate needs and building a strong and diverse teaching workforce. This post is part of the blog series, Solving Teacher Shortages.

As we take stock of the widespread teacher shortages that are grabbing daily headlines from South Carolina to California, important context is missing from the discussion: Well before COVID-19 upended schools, the teacher workforce in the United States was insufficient to meet the need. While there are many causes for these systemic shortages, one significant factor is the consistent underinvestment in the teacher pipeline. Unlike high-achieving countries, which have invested in the people, policies, and infrastructure needed to ensure students have access to quality teachers, in the United States, federal investments have been anemic, and federal policy has been fragmented. The COVID-19 staffing crisis presents an opportunity to break with old habits. Federal funding and social safety net bills that are pending in Congress contain what could be the start of deeper investment in the teacher pipeline.

Update: Fiscal Year 2022 Spending Bill

On March 15, President Biden signed into law the bipartisan Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 (also referred to as “the spending bill”), which funds the federal government for this fiscal year (FY). It includes a $2.9 billion (or nearly 6%) increase to Department of Education programs over FY 2021 levels.

While this marks the largest jump in funding in 15 years, it is far less than the 41% increase the Biden-Harris administration proposed for these programs in April 2021 and the House passed in July 2021. In addition to its spending proposal for FY 2022, the administration proposed $9 billion over 10 years for a well-prepared and diverse educator workforce as part of the Build Back Better plan.

Final funding for the four educator preparation programs in FY 2022 is as follows:

- Teacher Quality Partnership Program: $59.1 million

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Part D’s Personnel Preparation Program: $95 million

- Augustus F. Hawkins Centers of Excellence: funded for the first time at $8 million

- The School Leadership Recruitment and Support Program: not funded

In short, of the $432.1 million in funding that was proposed for these programs for FY 2022, $162.1 million was allocated—about $20 million more than was allocated in FY 2021.

The Importance of High-Retention Pathways

The foundation of a stable and diverse teacher workforce is the availability and affordability of high-retention pathways into teaching. Comprehensive preparation programs, like teacher residencies, pair intensive student teaching under the supervision of an expert mentor teacher with coursework in children’s learning and development, as well as curriculum and teaching methods, including how to differentiate instruction. Significantly, residencies offer financial support that underwrites all or most of the cost of preparing to teach in exchange for a service commitment of 3 to 5 years in an underserved school. New teachers also can expect to receive induction and mentoring support. This type of comprehensive preparation and early career support is also reflected in many Grow Your Own (GYO) programs.

Comprehensive and affordable preparation, together with induction support, is effective at keeping teachers in the profession. Nationally, teachers who enter the profession through programs that bypass intensive student teaching and coursework are 2 to 3 times more likely to leave the profession than those who enter through comprehensive preparation programs. An example from the San Francisco Unified School District demonstrates how this dynamic plays out at the local level. A study of teacher residencies in California found that after 5 years, 80% of graduates of the San Francisco Teacher Residency Program were still teaching in the district, compared with 38% of other beginning teachers.

Recognizing the important role residencies play in stemming teacher shortages and building a strong and diverse workforce, states such as West Virginia, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, California, and Mississippi are making investments in this strategy. These investments are a step in the right direction but don’t replace the important role the federal government can play in supporting widespread access to high-quality and affordable teacher preparation.

Research demonstrates that students take into account future earnings and the debt they will accumulate when making career choices. Comparatively low teacher wages and high college costs and student loan debt serve as disincentives for going into teaching. Governors from Georgia to New Mexico have recently taken steps to increase teacher salaries. In Alabama, for example, Governor Kay Ivey has proposed a 4% pay increase for teachers, while Idaho Governor Brad Little has proposed a 10% pay increase, as well as bonuses and increased contributions to health insurance premiums for teachers.

The Importance of Minimizing Debt

Existing grant and loan programs, which provide financial support to aspiring teachers, were enacted more than a decade ago with bipartisan support. They are in desperate need of updating to respond to today’s realities.

As a tool to recruit new teachers, the Teacher Education Assistance for College and Higher Education (TEACH) Grant provides approximately $4,000 a year in grant aid for educator preparation in exchange for a commitment to teach a high-need subject in an underserved school for 4 years. Since the program was created in 2007, student loan debt has grown by more than $1 trillion, while the grant award has decreased. Raising the award amount to $8,000 per year would better align the program with the current cost of comprehensive preparation and lower affordability barriers. Adjustments to the harsh penalty for failure to fulfill the service requirement (in which case the grant converts to a loan with interest), as well as continued efforts to improve administration, would make the program even more appealing.

The Teacher Loan Forgiveness (TLF) and Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) programs require teachers (and other public servants in the case of PSLF) to slog through years of monthly payments on low salaries before having part or all of their federal student loan debt canceled. These programs could be reconstituted to have the federal government make teachers’ monthly loan payments until they meet the service requirement to retire their debts completely. Doing so would save teachers hundreds of dollars each month and thousands of dollars over time, while delivering a much-needed boost to both recruitment and retention.

Finally, the current freeze on student loan payments—set to expire on May 1—has, in effect, boosted the salaries of teachers with federal student loan debt for nearly 2 years. For those pursuing loan forgiveness (and continuing to meet service requirements), time under the freeze is time credited toward loan forgiveness. Extending this freeze to the end of the next school year would serve as an effective retention tool to deal with emergency-level shortages. Should federal policymakers act on permanent loan reforms, the temporary measure can serve as an on-ramp to future enhanced supports to relieve debt burdens for teachers and others.

While progress on teacher compensation is a positive development, college affordability and student loan debt still loom. These barriers are especially high for students of color. For example, a study from the Brookings Institution found that Black students graduate college with $7,400 more debt than white graduates and that this gap quadruples over 12 years. Moreover, an analysis of federal financial aid data found that compared to other racial and ethnic groups, white students were the least likely to lack resources for college. Given these barriers, it’s not surprising that teachers of color enter teaching through alternative routes to certification at twice the rate of white teachers, avoiding added debt and enabling them to earn a salary while they teach and earn their credentials. Entry through these routes, which typically skip student teaching, leads to significantly higher attrition rates for these teachers, even after controlling for other aspects of their salary and working conditions.

While many aspiring teachers have no practical choice but to forego comprehensive—and costly—preparation, the high turnover rates among alternative pathways have profound negative consequences. Prior to COVID-19, 90% of open teaching positions were the result of teachers leaving the profession. Only 1/3 of leavers were retiring. Most left due to discouragement or dissatisfaction.

Chronic Failure to Invest in Preparation

The four federal programs discussed below support comprehensive educator preparation. Each was created or updated on a bipartisan basis, demonstrating broad-based understanding of the important federal role in building a strong and diverse teaching profession. Unfortunately, funding has been tepid at best across all these initiatives, despite the long-standing and growing need.

- Teacher Quality Partnership (TQP) Program: This is the federal government’s primary vehicle for investing in comprehensive educator preparation. The program funds teacher residencies, school leader preparation, and undergraduate- and graduate- preparation programs that include partnerships with underserved school districts and preparation programs at institutions of higher education. TQP-funded residencies also must provide participants stipends, an important tool to recruit and support diverse candidates. In the last full budget cycle, TQP received just over $52 million, well below the $300 million in annual spending Congress authorized when the program was created. This gap between authorized and actual spending has resulted in a $2.5 billion shortfall for TQP over the past decade.

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, Part D’s Personnel Preparation Program (IDEA-D-PP): This program supports the preparation of specialized instructional support personnel, special educators, early educators, and the higher education faculty and researchers who support their preparation. Through the use of scholarships, IDEA-D also reduces affordability barriers for prospective special educators. But while nearly every state and the District of Columbia face teacher shortages in this field, the program—funded at $90.2 million for the 2021 fiscal year—receives less funding today than it did in 2010.

- Augustus F. Hawkins Centers of Excellence: This program provides funding to support educator preparation at Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), and Minority Serving Institutions of higher education (MSIs). Although the Hawkins program was created well before the high school class of 2022 was in kindergarten, it has never been funded. Failure to do so limits the ability of these institutions, which have been a long-standing source of diverse and well-prepared teachers, to play an even stronger role in helping to meet current needs.

- School Leadership Recruitment and Support Program (SLRSP): This program provides grants to underserved school districts to support programs to recruit, train, and mentor school principals and assistant principals. Development and support of school site leaders is a critical component of addressing teacher turnover, since research shows that principal leadership and support are among the most important factors in teachers’ decisions about whether to stay in a school or in the profession. Congress renamed and updated the program in 2015, but SLRSP has yet to be funded.

More From the Blog Series

Potential Foundations for Change

There are two bills on Congress’s near-term docket that can start to reorient the federal government toward supporting comprehensive preparation: the 2022 fiscal year (FY) spending bill and the Build Back Better Act.

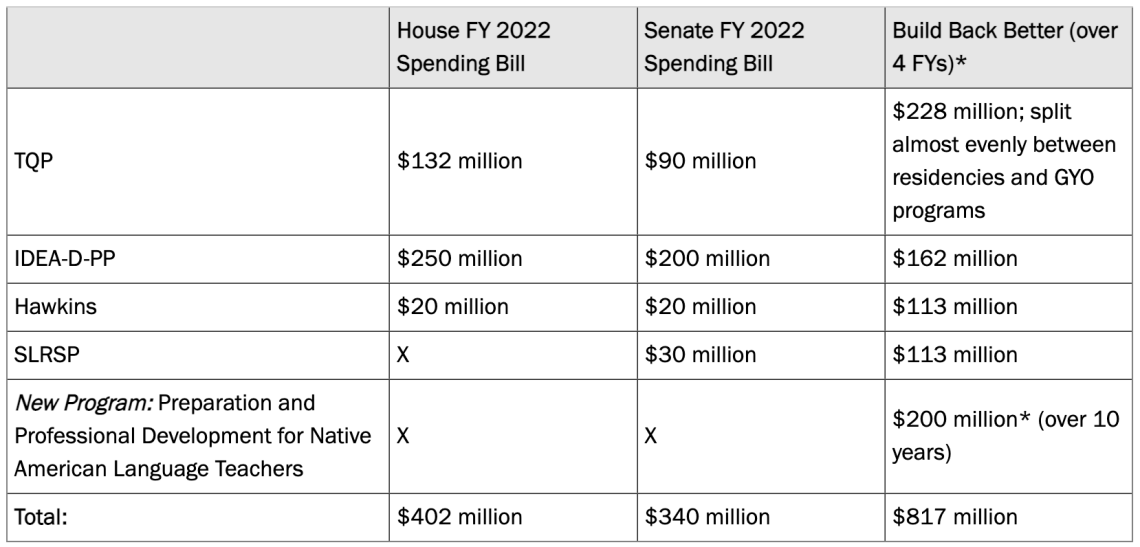

Spending bill: While the current 2022 FY began on October 1, 2021, Congress has yet to pass a spending bill and instead is relying on short-term stop-gap funding that temporarily continues FY 2021 spending levels. The House of Representatives passed its FY 2022 education-related funding bill in July, which increases funding for Department of Education programs by 41% over FY 2021 levels. The Senate education appropriations subcommittee released its bill in October, which included a 35% increase for Department of Education programs. While these are historic increases, at this writing these bills do not have bipartisan support. (See Figure 1, below.) If a bipartisan FY 2022 bill can be crafted and passed, the education levels in these partisan bills will change as part of the compromise. If bipartisan consensus is not reached, current discretionary funding levels—or lack of funding, as is the case with both Hawkins and the School Leadership program—will be locked in for another year.

Build Back Better: In April, the Biden-Harris Administration’s original Build Back Better (BBB) plan outlined a $9 billion investment over 10 years in a well-prepared and diverse educator workforce. In November, BBB passed the U.S. House of Representatives. Despite consistent and vocal support of the civil rights and education communities and many in Congress for this equity-focused investment, this bill now only includes $817 million over 4 years in direct investment in the educator workforce, spread across 5 programs. (See Figure 1, below.) Nonetheless, if BBB is enacted, funding would be mandatory and would not require annual Congressional approval, as is the case with the annual funding bills. While BBB is stalled, there are hopes that it will be revived in some fashion.

Figure 1: Proposed Spending on Federal Educator Preparation Programs

What About the Rescue Acts?

From March 2020 through March 2021, Congress passed three major COVID-19 relief bills that contained billions of dollars of aid to public k-12 schools and institutions of higher education, mainly through the Elementary and Secondary Schools Emergency Relief (ESSER) Fund, and the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund (HEERF), respectively. However, while rescue funds are and can be used at recipients’ discretion to address teacher shortages, including growing the teacher pipeline, the trio of laws did not provide direct support to expand educator preparation programs.

The ESSER funds allocated at least 90% of monies under flexible COVID-19-related terms to school districts, which do not have the same capacity as states to establish or grow educator-preparation programs. Meanwhile, the higher education funding was primarily designed to support institutional needs related to addressing the impacts of the pandemic and to provide emergency financial aid grants to students.

What’s Next?

Even in the rosiest (and unlikely) scenario, in which the highest proposed funding levels of the spending bills and the House-passed BBB bill are adopted, the federal government would still be only spending $636 million to support comprehensive educator preparation in FY 2022. That would represent barely five one-hundredths of a percent (about 0.05%) of all federal spending in last year’s government funding bill (about $1.4 trillion)—barely a drop in the ocean of government spending.

Meanwhile, in every state, classes are canceled, teachers and administrators do double-duty covering classrooms for their absent colleagues, and too many students flounder without the guidance of fully prepared and supported teachers. The federal government has tools—developed with bipartisan support—that can be used to address the immediate crisis and build for the long-term. These include programs to invest in educator preparation and development, as well tools to tackle college costs and student loan debt. The current crisis underscores the need and these bipartisan tools provide the vehicles for action. We have not a moment to lose.