Preparing West Virginia’s Teachers

In recent years, research on the science of learning and development has advanced rapidly, and calls for schools to provide all students with deeper learning experiences that prepare them for life and work in the 21st century have increased. Meeting these rising expectations will require educational systems to address the cognitive, sociocultural, and social-emotional aspects of learning and development in ways that meet the needs of every student. Teachers will play a vital role in any such realignment, since their qualifications, actions, and experience, as well as the strength of their preparation, affect students’ well-being and their learning. Further, research demonstrates that better-prepared teachers are not only more effective but are also more likely to stay in the profession longer. Therefore, policies that affect teachers and the teacher workforce, such as those that govern educator licensure and preparation program approval, will be key levers in ensuring that schools provide all students with equitable access to deeper learning experiences.

This report, one of a series of state policy studies produced by the Learning Policy Institute and the Council of Chief State School Officers, examines teacher licensure and preparation program approval systems in West Virginia. This study was designed to assess how these systems are advancing the preparation of a well-qualified and equitably distributed teacher workforce to support all students’ deeper learning and social, emotional, and academic development. This report describes the state policy context and the current system of teacher licensure and preparation program approval, and draws on contemporary research and state policy examples to provide recommendations aimed at systemic improvement and intended to help policymakers move closer to West Virginia’s teacher workforce goals.

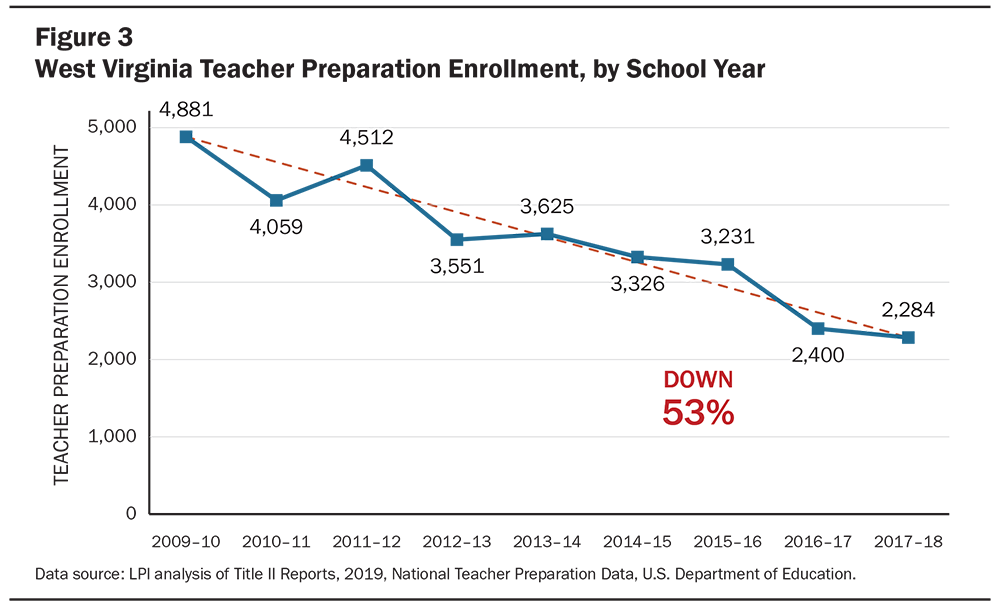

For example, one challenge of meeting the demand for fully prepared and certified teachers is the continued decline in teacher preparation enrollment across the state. Between the 2009–10 and 2017–18 academic years, West Virginia saw a 53% decline in the number of individuals entering teacher preparation programs (see Figure 3). This decline outpaces the national decline in teacher preparation enrollment, which is about 38%. However, during that period, West Virginia only saw a 12% decline in the number of program completers (compared with the national average of 28%). This suggests that the state has had more success than others nationally in moving candidates to program completion. Nonetheless, teacher supply is down overall. During the 2010–11 academic year, 1,133 individuals completed preparation programs in the state, while by 2017–18, that number was down to 994. Taken together, these numbers paint a mixed picture for teacher preparation across the state that could portend the continued decline in the state’s supply of new teachers.

Recommendations

The current policy landscape in West Virginia includes some strong policies designed to attract and prepare teachers (e.g., National Board Certified Teachers support, yearlong residencies, performance assessments, service scholarships, and loan forgiveness), though this report found that they are not necessarily resulting in widely available opportunities for high-quality preparation. Notable gaps in the policy landscape undermine preparation and teacher retention (e.g., by eliminating statewide induction standards, providing little oversight of new teacher induction funds, eliminating mentor certifications, and allowing the number of teachers who enter the profession without full preparation or on temporary certifications to increase). The following recommendations emphasize opportunities for the state to build a sustainable workforce; formalize its commitment to the social, emotional, and academic development of students; and ensure that the standards for teaching help shape the instruction and practices of teachers across the state.

Recommendation 1: Revise the West Virginia Professional Teaching Standards (WVPTS) to reflect current knowledge about student learning and development

For educators to develop the knowledge and skills needed to support the social, emotional, and academic development of students, West Virginia should initiate a revision of the WVPTS that govern systems spanning the educator career continuum. Broadly speaking, there is a need for the standards to reinforce that all learning depends on emotional safety and attachments and that teachers should possess the skills and knowledge to:

- model strategies and practices for learning as well as strengthening social and emotional skills;

- create positive conditions for learning through strong, supportive attachments and relationships;

- use educative and restorative behavioral supports to create positive, engaging, co-constructed classroom learning communities; and

- integrate social and emotional learning to foster self-regulation, executive function, perseverance, resilience, and a growth mindset.

Further, although county leadership and staff at the department consistently mentioned the need for trauma-informed practices, these practices are not mentioned in the current standards. The standards should stress the need for educators to use trauma-informed and healing-informed approaches to learning that build awareness of students’ needs and support the development of their regulatory abilities.

Finally, the teaching practices highlighted above should be cultivated and expected of all teachers, both new and practicing, and the progressions in the WVPTS should support and clarify this. Specifically, practices meant to support all students and aligned to broader statewide priorities around social and emotional learning should be incorporated beyond the Distinguished category of practice under the standards.

Recommendation 2: Ensure that teacher performance assessments reflect West Virginia’s standards for teaching in action and inform program improvement

Over the past 6 years, West Virginia has taken strong initial steps toward implementation of a performance assessment requiring candidates to demonstrate teaching competencies aligned to state standards before their program recommends them for a license. The state’s policy of providing flexibility for preparation programs in the choice of performance assessment helped give rise to the West Virginia Teacher Performance Assessment (WVTPA), which is currently used by 15 of 19 institutions in the state. The assessment, aligned to the WVPTS, is rigorous and contains the important assessment elements found in current national assessments, such as requiring candidates to plan and teach a unit, submit videos of their teaching, and track student progress and outcomes through an assessment plan. However, because the WVTPA has been in use only since 2016, it is still early to assess its effectiveness across the system. Additionally, because state policy allows programs to choose their performance assessment, there remains significant variability in how this requirement is met. In an effort to address the variability while still maintaining the flexibility in policy afforded to programs, West Virginia could begin by:

- improving the scoring and calibration of the WVTPA;

- ensuring that programs have access to their performance assessment data and are using it to inform program improvement; and

- utilizing statewide and program-level performance assessment data to inform policy, specifically around the ongoing implementation of the yearlong residency.

Recommendation 3: Strengthen clinical training by supporting productive teacher residencies

Policy changes in 2021 provided greater structure within which institutions can build their yearlong residency pathways and tailor them to meet candidates’ needs and those of their k–12 partners. For example, cooperating teachers are compensated for working with a teacher resident, and residents can receive limited compensation by substitute teaching at their residency school.

Yet, looking ahead, scaling these yearlong residency pathways requires building an effective cadre of cooperating teachers. Further, with limited funding through the residency grant program, a deep need remains for the state and programs to establish sustainable residency funding. Finally, preparation programs still need support through partnerships with k–12 schools. To ensure the quality and sustainability of the yearlong residency pathway, the state could:

- support the recruitment and training of quality cooperating teachers;

- pilot sustainable funding strategies for the yearlong residencies that support stipends for cooperating teachers and residents; and

- convene statewide and regional collaboratives that support strong partnerships between k–12 schools and teacher preparation programs, help residency programs learn and improve with each cohort of residents, and study the progress toward successful scaling of the residency program.

Recommendation 4: Support improvements in accreditation and data use

In West Virginia, current program approval policy and related data systems yield limited data that the state and individual programs can use in their continuous improvement efforts. Further, it is unclear, based on conversations with preparation program staff and leadership, how data collection and analysis efforts linked to national accreditation can support meeting the social and emotional needs of teachers and students across the state. With policy changes proposed in 2021, the state has an opportunity to drive conversations about how programs can use data in their improvement efforts. To support performance-based accreditation and continuous improvement across programs, the state could:

- support improved collection and use of data, including employer and preparation program completer surveys, performance assessment results, and data on the number of candidates and completers by pathway within an institution (e.g., alternative certification, teacher-in-residence, yearlong residency); and

- build on proposed policy changes allowing for multiple national accreditors by working closely with both the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation and the Association for Advancing Quality in Educator Preparation to ensure more direct support to programs for their continuous improvement efforts that are aligned to the state’s current priorities and student needs.

Recommendation 5: Strengthen and expand efforts to address persistent teacher shortages

Publicly available data on the supply and demand of the teacher workforce in West Virginia is limited and often opaque to the point of limiting potential policy responses. The data in this report on the nature of teacher shortages across the state were pulled from local news stories or data sources that have grown increasingly outdated. The state’s primary education data dashboard, ZoomWV, which has a stated goal of “helping stakeholders support all students’ achievement,” offers data on the distribution of teachers based on their years of experience, but it has an empty field under a teacher education heading. Given documented challenges in meeting the state’s persistent demand for fully prepared teachers across the state, West Virginia could:

- increase access to data tracking the supply and demand of the teacher workforce, including accurate data on teacher vacancies, turnover, and the number of individuals—by subject area—entering teaching through First-Class/Full-Time Permits, Teacher-in-Residence pathways, and Alternative Certification; and

- track and measure the impact of the recently expanded Underwood-Smith Teaching Scholars Program to determine its efficacy in meeting workforce needs.

Recommendation 6: Strengthen induction to support teacher effectiveness and retention

Induction and mentoring for new teachers increase their likelihood of staying in the classroom and protect investments in teacher preparation often lost to early-career attrition. While there is a statewide requirement for new teacher induction, and a source of funding for that support, there is little statewide infrastructure that ensures access to quality mentoring and support for all new teachers. To address the inadequate access to and inconsistent quality of induction and mentoring supports, and to tackle the high rate of attrition of beginning teachers across the state, especially in hard-to-staff schools, West Virginia could:

- establish systems for tracking and measuring the impact of beginning teacher support funds distributed to counties; and

- set minimum requirements for beginning teacher induction that support teacher retention, are aligned with research, and provide for local control and implementation.

Further, when it considers the induction supports available to novice teachers, the state could include those novice teachers who are serving as teachers of record but are still completing their training through one of the state’s critical need and shortage pathways (First-Class/Full-Time Permit, Teacher-in-Residence Permit, and Alternative Certification). Because these novice teachers are not required to complete a structured clinical experience, they may never observe a good teacher or get intensive support from an expert teacher during their own training. This will also include individuals who are entering the profession on the alternative pathway created during the 2021 legislative session through SB 14, who will likely enter the classroom with few opportunities to practice or build the skills needed to support the learning of all students. To ensure that these individuals receive the training and support they need to remain in the classroom and provide the learning experiences West Virginia students need, the state could:

- explicitly define and monitor induction and mentoring supports across the alternative certification pathways.

Finally, efforts to expand the number and distribution of National Board Certified Teachers (NBCTs) in West Virginia hold promise for supporting a range of needs across the state’s systems for professional learning. NBCTs can serve as cooperating teachers for yearlong residents and mentor new teachers through county induction programs. To better leverage NBCTs as resources within the state’s professional learning system, West Virginia could:

- more equitably distribute teaching expertise by improving the implementation of the state’s stipend available to NBCTs working and serving as mentors in hard-to- staff schools, and

- increase the number of NBCTs serving as mentors and cooperating teachers.

Conclusion

These six recommendations build on West Virginia’s recent moves to strengthen the quality of preparation available to new teachers across the state. They are primarily meant to shore up efforts to implement the yearlong residency and ensure that investments in the recruitment and retention of teachers across the state drive student learning. Applying these recommendations to shape educator preparation and practice can help move the state closer to having a well-qualified and equitably distributed teacher workforce able to support the whole child and students’ social, emotional, and academic development. Further, while the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have reshaped the landscape in which these recommendations may be implemented, there are promising opportunities through current and future federal investments that could support the state in strengthening licensure and program approval and help schools weather today’s challenges and evolve to meet those of the future.

Preparing West Virginia’s Teachers: Opportunities in teacher licensure and program approval by Ryan Saunders is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, and Sandler Foundation. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.