California Teacher Shortages: A Persistent Problem

Summary

A highly competent teacher workforce is a necessary foundation for improving children’s educational outcomes, especially for those who rely most on schools for their success. Yet a survey of over 200 California school districts reveals that three out of four districts report having a shortage of qualified teachers and that this shortage has gotten worse in the past two years. Districts report having to hire untrained teachers and substitutes, assign teachers out of field, cancel courses, and increase class sizes. They also report efforts to respond to shortages with a variety of policies to strengthen teacher preparation partnerships and pathways into the district, increase compensation, improve hiring and management, and enhance working conditions. To better address shortages, particularly in high-need fields and schools, the state and districts will need to develop a variety of evidence-based strategies targeted to communities' different needs.

Introduction

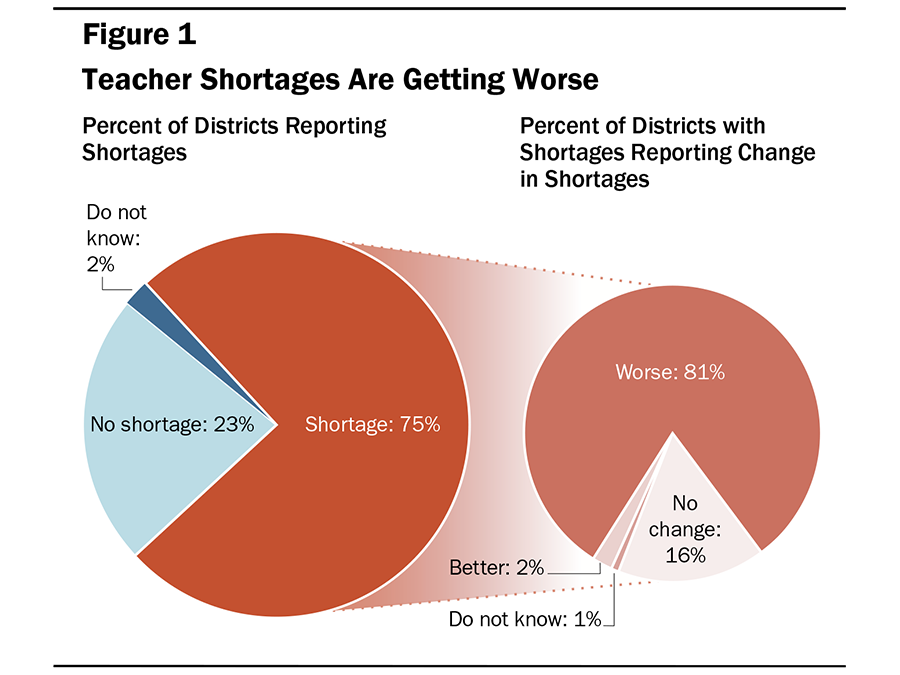

In the fall of 2016, a survey of 211 school districts in the California School Boards Association’s Delegate AssemblyThe California School Boards Association's (CSBA) Delegate Assembly represents 244 unique California school districts out of California’s roughly 1,025 total school districts. The Delegate Assembly provides a regionally representative governance structure for CSBA. Our sample includes 211 unique districts that fully completed the survey—representing a response rate of over 84%. Partial respondents (i.e., districts that answered less than 20% of the survey) and duplicate respondents (districts that had multiple people complete the survey) were removed, using random selection when appropriate. The demographic characteristics of the school districts included in this sample generally reflect the demographics of the approximately 1,025 districts throughout California. However, this sample may differ from the population of all California districts because, for example, it includes a larger percentage of districts from cities and suburbs.—a sample that generally reflects the demographics of California’s districts—revealed that they are experiencing alarming rates of teacher shortages.The CSBA and the Learning Policy Institute partnered in summer 2016 to create and administer a survey of district-level leaders to learn about the extent to which they were experiencing shortages of qualified teachers, principals, and school leaders, and to learn about the various policies and practices districts use to attract and retain educators. The survey was sent to school board members who participate in CSBA’s Delegate Assembly. Board members typically sent the survey to the person in the district who they thought would know the most about the district’s personnel practices. Individuals in the following positions completed the survey: 37% Assistant Superintendents; 33% Human Resource Directors; 9% Superintendents; 21% Other (e.g., Board Member, Human Resource Analyst, Personnel Manager). Approximately 75% of districts report having a shortage of qualified teachers for the 2016–17 school year. Over 80% of these districts say that shortages have gotten worse since the 2013–14 school year (see Figure 1).

Shortages Impact California Students, Especially High-Need Students

While teacher shortages are concentrated in districts serving California’s most vulnerable student populations, large majorities of all kinds of districts are experiencing shortages:

- 83% of districts serving the largest concentrations of low-income students“High-poverty” or “the largest concentrations of low-income students” refers to districts in the top quintile of free and reduced-price lunch eligible student enrollment. “Low-poverty” refers to districts in the bottom quintile. “The largest concentrations of students of color” refers to districts in the top quintile of non-white student enrollment. “The largest concentrations of English learners” refers to districts in the top quintile of English learner enrollment. report having shortages, compared to 55% of districts with the fewest.

- 83% of districts with the largest concentrations of English learners report having shortages, compared to 64% of districts with the fewest.

- 83% of districts with the largest concentrations of students of color report having shortages, compared to 57% of districts with the fewest.

Teacher shortages are reported more frequently in cities (87% of districts in cities report shortages) and rural areas (82%) than in towns (72%) and suburbs (69%).

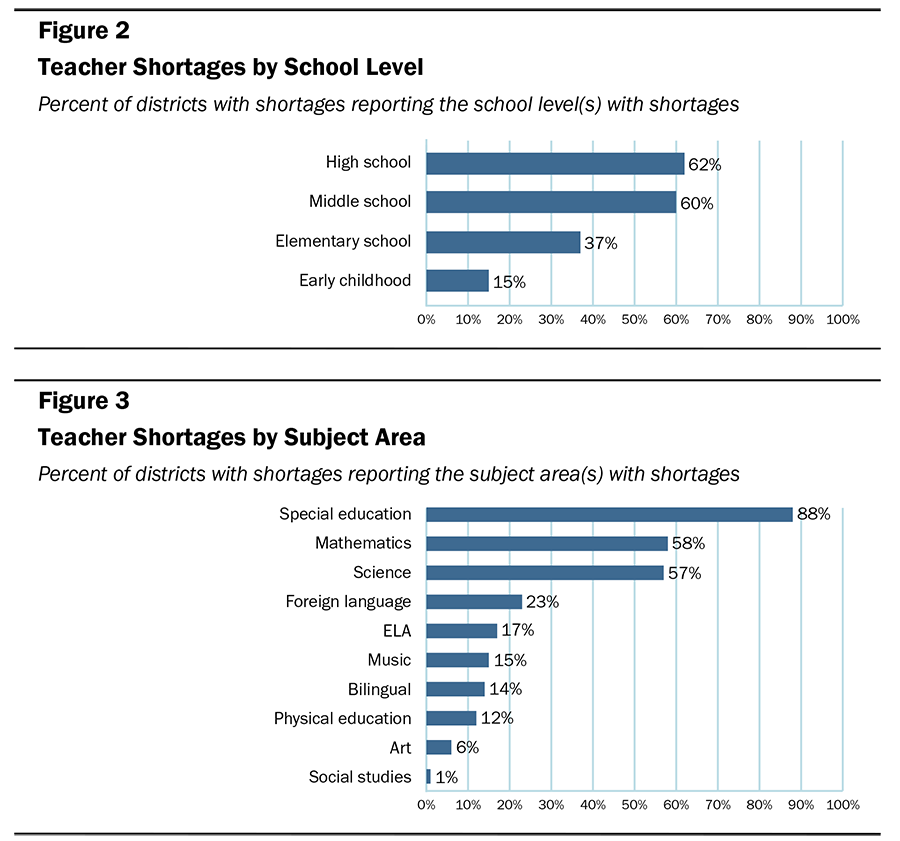

Of districts that report shortages, most districts report not having enough middle and high school teachers—especially in math and science, and nine out of 10 report shortages in special education (see Figures 2 and 3). More than one out of three reported shortages of elementary teachers.

Fourteen percent of districts with shortages report not having enough bilingual education teachers. This shortage will likely increase because of the recent passage of Proposition 58, which once again allows bilingual education within California public schools.

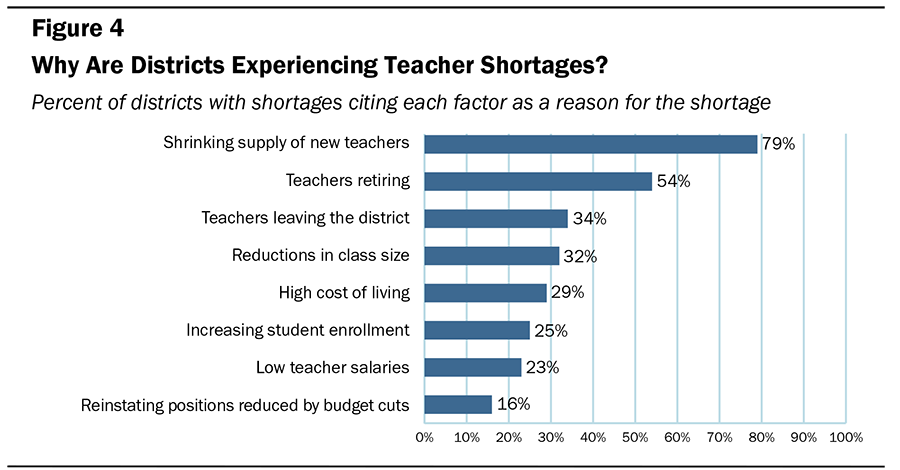

Districts are experiencing shortages for a variety of reasons. Seventy-nine percent of the districts that reported shortages said that they are experiencing shortages because of the shrinking supply of newly credentialed teachers. In fact, one respondent commented:

After nine years in my position, I see the decline each year in fully credentialed teachers completing their university programs.

Other frequently cited explanations for shortages include teachers retiring, teachers leaving the district, reductions in class size, and the high cost of living (see Figure 4). Not surprisingly, city and suburban districts attribute teacher shortages to a high cost of living more frequently than districts located in rural and town settings. Additionally, high-poverty districts report teacher turnover as a reason why their district is facing shortages twice as often as low-poverty districts.

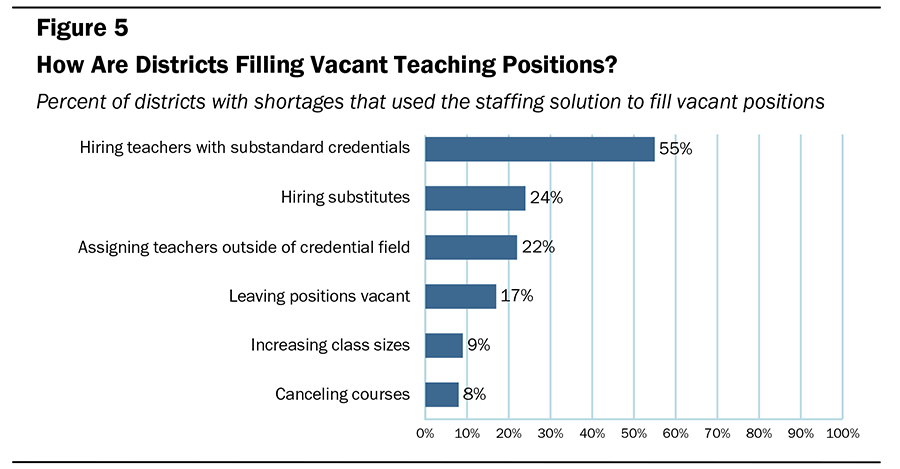

Of the districts that reported having trouble filling their vacancies, nearly two-thirds were unable to staff all positions with individuals who had full credentials in the appropriate subject or grade level. As a result, districts are finding teachers to fill classrooms through a variety of less than ideal practices, ranging from hiring teachers with substandard credentials to hiring substitutes, assigning teachers to teach out of their credential field, or leaving positions vacant (see Figure 5).

High-poverty districts report filling their vacancies with teachers who have substandard credentials more than twice as often as low-poverty districts (71% vs. 30%). They also report filling vacancies more often with substitute teachers (29% vs. 13%). In addition, over three-quarters of districts noted that they hired teachers late into the summer or after the school year began, with close to 60% of districts saying they hired late because they could not find enough qualified teachers. High-poverty (68%) and rural districts (80%) more frequently report hiring teachers late compared to low-poverty (41%) and more urban districts (64%). Some research suggests that, on average, teachers hired after the start of the school year are generally less effective and more likely to leave the teaching workforce than other newly hired teachers.Liu, E., & Johnson, S.M. (2006). New teachers’ experiences of hiring: Late, rushed, and information-poor. Educational Administration Quarterly, 42(3), 324–360; Papay, J.P., & Kraft, M.A. (2015). Delayed teacher hiring and student achievement: Missed opportunities in the labor market or temporary disruptions?; Jones, N.D., Maier, A., & Grogan, E. (2011). The extent of late-hiring and its relationship with teacher turnover: Evidence from Michigan. Unpublished manuscript.

Administrator Shortages

While teacher shortages are most severe, some districts (about 7%) are also beginning to experience shortages of principals and district-level administrators. These shortages are mostly identified in districts with the highest concentrations of low-income students, English learner students, and students of color. In addition, rural districts report principal shortages more frequently than city districts (27% rural vs. 4% city). Of the districts reporting administrator shortages, over half say that the shortage of principals and district-level administrators is getting worse. One respondent commented:

We are finding the pool of folks wanting to be high school administrators to not be as robust as past years. We hear the hours and challenges are not attractive to everyone.

California District Policy Responses

Districts report adopting a variety of strategies to recruit and retain qualified teachers. These strategies include policies and practices that affect teachers’ preparation and pathway into the profession, compensation, hiring and management, and working conditions. Many districts are working on recruitment and retention simultaneously. For example, one district respondent noted:

We are planning to work on … developing high school career pathways. … [And] in partnership with our teachers’ union, we are beginning purposeful initiatives to retain new teachers that are hired, including a school site support system, avoiding overwhelming first-year teaching assignments, limiting out-of-class time for professional development, and providing a take-home notebook computer for professional use.

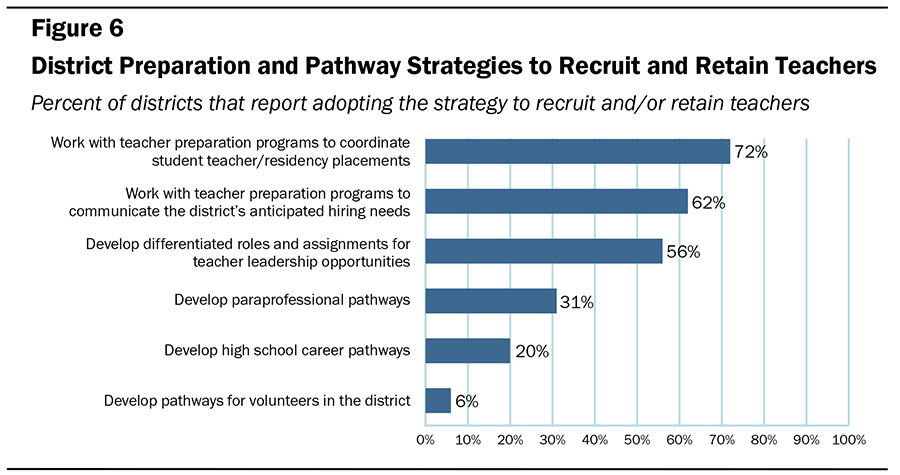

Teacher Preparation and Pathway Strategies (93% of districts): Almost all districts—both urban and rural alike—report adopting one or more teacher preparation strategies for recruiting and retaining teachers (see Figure 6). Most work with higher education to coordinate student teaching or residency programs and communicate hiring needs. Urban and rural teacher residencies have been successful in recruiting talented candidates into high-need fields to work as paid apprentices to skilled expert teachers as part of their preparation.Guha, R., Hyler, M.E., and Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The teacher residency: An innovative model for preparing teachers. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. A smaller percentage of districts—mostly urban—report creating pathways into the teaching profession for high school students, paraprofessionals, and district volunteers. These programs, sometimes referred to as Grow Your Own teacher preparation models, recruit talented individuals from the community into a career in education and help them along the pathway into the profession.Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

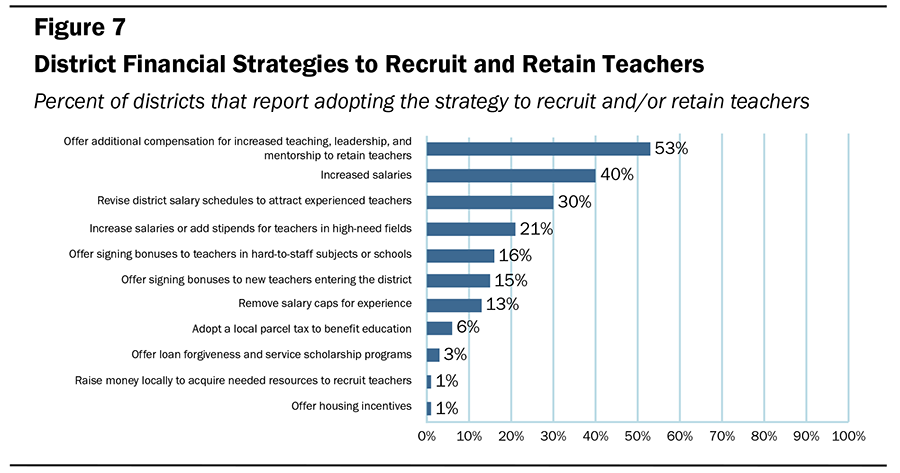

Financial Strategies (74% of districts): Many districts report adopting financial strategies to recruit and retain teachers (see Figure 7). Several studies show that teachers’ compensation can affect the supply of teachers, including the distribution of teachers across districts, and the quality and quantity of individuals preparing to be teachers.Adamson, F., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2012). Funding disparities and the inequitable distribution of teachers: Evaluating sources and solutions. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 20(7) 1–46. Districts most frequently report providing additional compensation for teachers who assume leadership roles. Multiple studies indicate that teachers who have opportunities to share their expertise through leadership roles are less likely to leave the profession and more effective at raising student achievement.Booker, K., & Glazerman, S. (2009). Effects of the Missouri Career Ladder Program on Teacher Mobility. Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.; Leithwood, K., & Mascall, B. (2008). Collective leadership effects on student achievement. Educational Administration Quarterly, 44(4), 529–561.

In addition to raising salaries, some districts are adding stipends for teachers in high-need fields, offering signing bonuses to new teachers, or removing salary caps for experience. A few districts offer loan forgiveness or service scholarship programs, which can be promising strategies to recruit and retain high-quality teachers into the fields and communities where they are most needed, especially when the financial benefit meaningfully offsets the cost of preparation.Podolsky, A., & Kini, T. (2016). How effective are loan forgiveness and service scholarships for recruiting teachers? Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. In general, financial strategies were more frequently used in shortage districts located in rural and town settings (77%) than in districts located in cities (63%) or suburbs (45%).

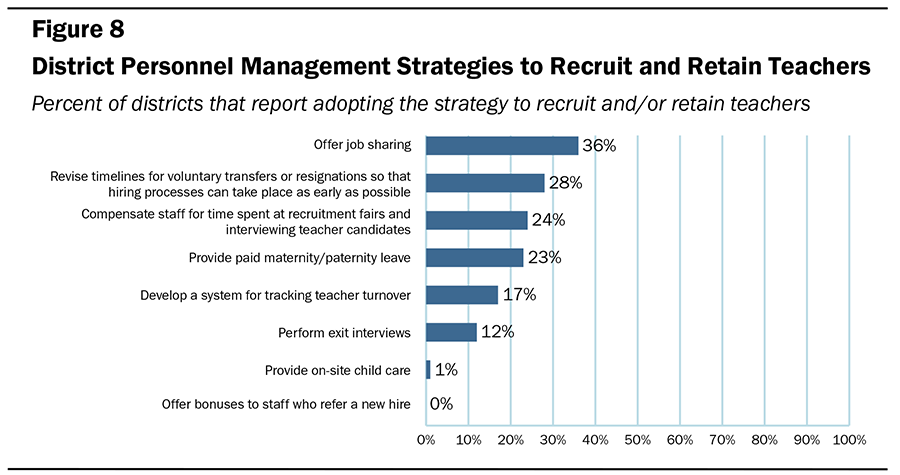

Personnel Management Strategies (55% of districts): Over half of districts report adopting personnel management strategies to facilitate recruiting and retaining teachers. Schools and districts that adopt effective hiring practices are, unsurprisingly, generally more successful at attracting and hiring effective teachers, leading to greater rates of schoolwide achievement.Loeb, S., Kalogrides, D., & Béteille, T. (2012). Effective schools: Teacher hiring, assignment, development, and retention. Education Finance and Policy, 7(3), 269–304. Some of these strategies aim to make teaching more compatible with raising a family, such as offering job sharing and paid maternity/paternity leave (see Figure 8). Others support recruitment by moving up hiring timelines or supporting staff to participate in recruitment fairs. Very few districts have adopted personnel strategies to specifically recruit teachers into shortage areas.

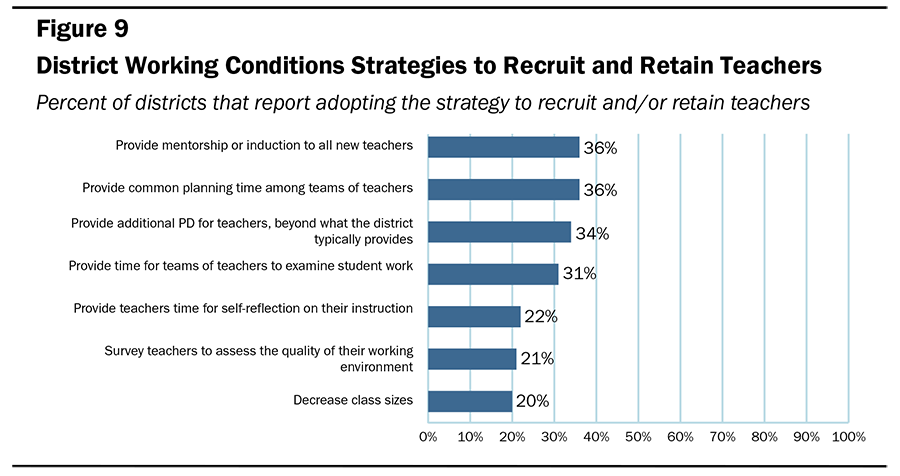

Working Conditions Strategies (40% of districts): Many districts—especially in cities and towns—report adopting working conditions strategies to recruit and retain teachers—a wise approach given the influence of working conditions on teacher retentionPodolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. (see Figure 9). More than one-third provide mentoring for new teachers, additional professional development for all teachers, and common planning time for teacher teams as retention strategies.

Many of the working conditions strategies involve teachers spending more time together collaborating. More collaborative work environments, where professional learning and collective responsibility are emphasized, can have a positive effect on teacher retention.Pogodzinski, B., Youngs, P., & Frank, K.A. (2013). Collegial climate and novice teachers’ intent to remain teaching. American Journal of Education, 120(1), 27–54; Goodpaster, K.P., Adedokun, O.A., & Weaver, G.C. (2012). Teachers’ perceptions of rural STEM teaching: Implications for rural teacher retention. Rural Educator, 33(3), 9–22; Heineke, A.J., Mazza, B.S., & Tichnor-Wagner, A. (2014). After the two-year commitment: A quantitative and qualitative inquiry of Teach For America teacher retention and attrition. Urban Education; Waddell, J.H. (2010). Fostering relationships to increase teacher retention in urban schools. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 4(1), 70–85. Collaboration generally requires adequate time for planning and adequate teaching and learning resources.Futernick, K. (2007). A possible dream: Retaining California teachers so all students learn (Vol. 2, No. 10). Sacramento, CA: California State University. Districts that provide time for teachers to collaborate most frequently do so by organizing time in longer blocks so that teachers have longer time periods to plan and collaborate together (28%) and by providing additional compensation for teachers for the time they spend collaborating (24%). One district noted how its supportive working conditions influence the district’s recruitment:

Fortunately, our district enjoys a wonderful reputation throughout the state; and, as a result, we are able to attract teachers, principals, and district-level administrators. We have in-house staff development and leadership training at all levels to continue to develop our own.

Conclusion

Three-quarters of the California districts surveyed by CSBA and LPI are struggling to find qualified teachers. And their struggle is getting worse. As one district administrator noted, “I believe the worst is still to come. … [I]n the end, the students lose.” Districts say these shortages are driven by a declining supply of teachers, combined with high turnover, ongoing retirements, and a growing number of positions to be filled. In response, many districts, especially districts with higher concentrations of low-income and English learner students, are hiring teachers with substandard credentials at best or leaving positions vacant at worst. Not only does some research indicate that teachers with substandard credentials are generally worse for student outcomes,Darling-Hammond, L., Holtzman, D.J., Gatlin, S.J., & Heilig, J.V. (2005). Does teacher preparation matter? Evidence about teacher certification, Teach For America, and teacher effectiveness. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 13(42); Clotfelter, C.T., Ladd, H.F., & Vigdor, J.L. (2007). Teacher credentials and student achievement: Longitudinal analysis with student fixed effects. Economics of Education Review, 26(6), 673–682. but they also leave at two to three times the rate of fully prepared teachers.Ingersoll, R.M., Merrill, L., & May, H. (2014). What are the effects of teacher education and preparation on beginning teacher retention? Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education.

Districts have responded to their shortages with a variety of policies to strengthen teachers’ preparation and pathway into the district, increase their compensation, improve their hiring and management, and enhance their working conditions. However, these policies have generally not been targeted to shortage fields. To address shortages, particularly persistent shortages in high-need fields and schools, and improve California students’ educational opportunities, the state and districts will need to consider expanding the range of evidence-based teacher recruitment and retention strategies that can meet each district’s unique context.

This brief is published jointly by the Learning Policy Institute and the California School Boards Association.

California Teacher Shortages: A Persistent Problem by Anne Podolsky and Leib Sutcher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by grants from the Stuart Foundation and the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation.