Preparing Transitional Kindergarten to 3rd Grade Educators Through Teacher Residencies

Summary

In California, 2021 legislation expanded transitional kindergarten (TK) to be universal for all 4-year-olds by 2025–26. This expansion will require an additional 11,900 to 15,600 credentialed teachers. Given projected workforce needs and historic investments in teacher preparation, early childhood–focused residencies can help districts strategically build TK teacher workforces. This brief describes two early childhood residency programs—Fresno’s Teacher Residency Program and UCLA’s IMPACT program—to help inform the development of strong early learning–focused residencies.

Research shows that high-quality early childhood education programs can have positive and lasting effects on children’s academic achievement and behavioral outcomes.Meloy, B., Gardner, M., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). Untangling the evidence on preschool effectiveness: Insights for policymakers. Learning Policy Institute. Based on this body of research, states across the country have been working to expand access to early childhood education programs.Wechsler, M., Kirp, D., Tinubu Ali, T., Gardner, M., Maier, A., Melnick, H., & Shields, P. (2016). The road to high-quality early learning: Lessons from the states. Learning Policy Institute.

California is one state that has shifted policy to provide universal access to early childhood education for all 4-year-olds. Transitional kindergarten (TK), launched in 2010 for older 4-year-olds, is the first of a 2-year public school kindergarten program intended to provide developmentally appropriate learning experiences for 4-year-olds.California Education Code § 48000 (d) (2021). California expanded TK in 2021, making it universal for all 4-year-olds by 2025–26 and establishing minimum child-to-adult ratios of 10 to 1, assuming funding is available.California Education Code § 48000 (g) (2021).

The expansion of TK—which, in California, essentially adds another public school grade—creates a significant new demand for credentialed teachers with early childhood expertise.TK requires a Multiple Subject (i.e., elementary) teacher certification. In addition, because of the expertise required for working with younger children, 2014 legislation required that, by August 1, 2020, teachers assigned to TK classrooms before July 1, 2015, complete at least 24 units of early childhood or child development coursework, hold a child development permit, or have equivalent professional experience as determined by the employing district. In 2021 this deadline was extended to August 1, 2023, to give districts more time to meet this requirement; California Education Code § 48000 (g) (2021). In 2019–20, nearly 89,000 children enrolled in TK, representing 71% of eligible 4-year-olds based on the original birthdate cutoff of December 2.LPI analysis of the Transitional Kindergarten Data, 2019–20, California Department of Education. That number of eligible children will increase as the age of eligibility gradually expands by several months each year until universal eligibility for all 4-year-olds in 2025–26. A Learning Policy Institute (LPI) analysis estimates that by 2025–26, more than 447,700 children will be eligible for TK, with between 291,000 and 358,000 children enrolled, depending on the rate of uptake. In turn, TK will require an additional 11,900 to 15,600 credentialed teachers with early childhood expertise.Melnick, H., García, E., & Leung-Gagné, M. (2022). Building a well-qualified transitional kindergarten workforce in California: Needs and opportunities. Learning Policy Institute. The state can draw on existing pools of current Multiple Subject credential holders, current early childhood educators, and new candidates, but most potential TK teachers will require at least some additional preparation.

High-Quality Teacher Residencies

Teacher preparation residency programs can help address this urgent need for new teachers. A growing body of research shows that teacher residencies are a strong model for recruiting, preparing, and retaining teachers.Guha, R., Hyler, M. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The teacher residency: An innovative model for preparing teachers. Learning Policy Institute. Teacher residencies are modeled on medical residencies’ intensive, hands-on supervised preparation. Through university–district partnerships, teacher residencies provide a pathway to a teaching credential in which candidates serve as paid apprentices working with skilled expert teachers while completing highly integrated coursework. Residencies can offer a pathway into teaching for recent college graduates, career changers, and educators who have been working in schools but are not yet certified to be teachers of record in a TK–12 setting.

Research has identified multiple characteristics of high-quality teacher residencies. Typically, strong residencies are designed to address specific instructional and hiring needs of school districts, provide yearlong clinical experiences in which residents are working 4 to 5 days a week under the guidance of an experienced mentor teacher, and provide financial supports for residents. These and other key characteristics of the residency model (see “Common Features of a High-Quality Teacher Residency”) make early childhood–focused (i.e., TK or p–3) residencies part of a multipronged solution to quickly prepare a large number of highly qualified, diverse teachers. With California expanding access to residency funding through grants, many school districts have already expressed interest in using funds to expand the supply of TK teachers.With 19 of 39 teacher residency capacity-building grants recently approved by the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing focused on TK and kindergarten residencies, early data suggest there is strong interest from districts and teacher preparation program partners in developing such programs. California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2022). 2021 Teacher Residency Capacity Grants round 1 funding, February 2022. (accessed 03/24/22).

This brief describes two early childhood–focused residency programs in California: the Fresno Teacher Residency Program and the UCLA IMPACT program. It describes each program’s coursework, clinical experiences, resident and mentor supports, and program outcomes, including perspectives from former residents, program leaders, and mentor teachers. Data sources include program documents and artifacts, interviews with program leaders and graduates, and publicly available recordings of events and documentary videos.

Common Features of a High-Quality Teacher Residency

High-quality teacher residency programs share common characteristics identified in research. Residencies typically:

- consist of strong partnerships between school districts, universities, and sometimes other organizations such as teacher associations or nonprofit support providers;

- tightly integrate coursework about teaching and learning with classroom practice;

- require a full year of residency teaching working alongside an accomplished mentor teacher;

- recruit diverse candidates for specific district instructional and hiring needs, often in shortage areas;

- provide financial support for both preparation and living expenses, often in exchange for the resident’s commitment to teach in the district for a minimum number of years;

- place cohorts of residents in “teaching schools” that model evidence-based practices with diverse learners; and

- offer ongoing mentoring and support for residency graduates hired by the partner district after they enter the teaching workforce.DeMoss, K. (2018). Following the money: Exploring residency funding through the lens of economics. Bank Street College of Education, Prepared To Teach. (accessed 04/18/22); Espinoza, D., Saunders, R., Kini, T., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2018). Taking the long view: State efforts to solve teacher shortages by strengthening the profession. Learning Policy Institute; Guha, R., Hyler, M. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The teacher residency: An innovative model for preparing teachers. Learning Policy Institute.

Fresno TK–3 Teacher Residency Program

From 2017 to 2019, in response to district workforce needs, the Fresno Teacher Residency Program offered two special cohorts focused on preparing teachers specifically for TK through 3rd grade. The 18-month program was part of Fresno Unified School District’s strategic workforce pipeline and included a focus on child development and STEM in the early grades, leading to a Multiple Subject (elementary) teaching credential and master’s degree in curriculum and instruction.

When it launched the TK–3 teacher residency, Fresno Unified had already been running residency programs in partnership with California State University, Fresno, for 5 years. These residency programs—originally launched with a federal Teacher Quality Partnership (TQP) grant—had proven to be a key part of the workforce pipeline for Fresno Unified, a large district located in California’s Central Valley serving over 73,000 students, 86% of whom are from low-income families and 19% of whom are English learners.California Department of Education. (n.d.). District profile: Fresno Unified. (accessed 03/24/22). The district expanded its existing residency program to prepare TK–3 teachers to meet its acute hiring needs for well-prepared TK and early-grade teachers with the support of a grant through the California State University New Generation of Educators Initiative.

Jeanna Perry, Manager of Teacher Development in Fresno Unified, shared that the early-grade focus of these cohorts was “determined by the district’s hiring needs. We really looked at what positions we needed to fill and what the areas of growth were within Fresno Unified.” As the district was beginning to expand the number of TK classrooms in response to state policy, district residency leaders worked closely with human resources administrators to strategically determine the number of candidates they would need to fill projected vacancies in TK through 3rd grade and recruited applicants based on these projections.

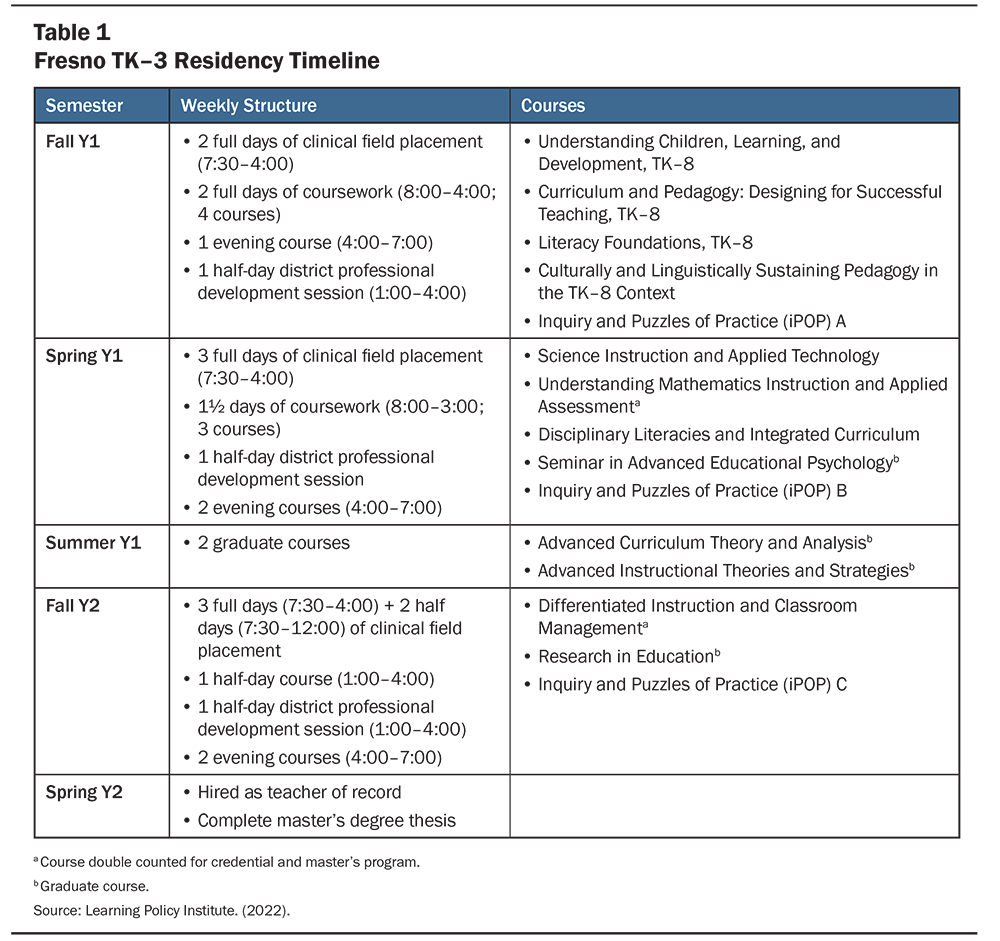

The district focused its new cohorts specifically on early learning because it recognized that working with young children in the early grades requires content expertise that is not typically included in elementary teacher preparation programs. According to Perry, the cohorts focused on three main areas of content: early literacy, developmentally appropriate practices, and social and emotional learning. The program also focused on family engagement strategies, a key component of early learning that supports continuity of learning both in and out of the formal classroom and that has been associated with positive developmental and academic outcomes.Meloy, B., & Schachner, A. (2019). Early childhood essentials: A framework for aligning child skills and educator competencies. Learning Policy Institute; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, & U.S. Department of Education. (2016). Policy statement on family engagement from the early years to the early grades. (accessed 05/13/22). See Table 1 for specific courses and how they were integrated with the clinical requirements of the residency.

Program Approach

The program taught residents developmentally appropriate instructional strategies for young children that reflect the research on the science of learning and development, which documents the importance of active learning opportunities that integrate different content areas in authentic ways that resemble how we experience work and life in the real world.Darling-Hammond, L., Cantor, P., Hernàndez, L. E., Schachner, A., Plasencia, S., Theokas, C., & Tijerina, E. (2021). Design principles for schools: Putting the science of learning and development into action. (accessed 04/13/22); Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140.

Project-based learning, a form of active learning that develops students’ knowledge and skills through investigations of complex problems or questions,Learning Policy Institute, & Turnaround for Children. (2021). Design principles for schools: Putting the science of learning and development into action. was an important program component in two ways. First, in teacher preparation courses, instructors used active learning techniques. For example, the residents identified puzzles of practice, such as how to help children overcome learned helplessness, how to better collaborate with families, and how to support a child with selective mutism, and engaged in ongoing inquiry by collecting and analyzing data to inform their practices. Second, residents learned to use these techniques in their classrooms. As Lisa Bennett, a literacy course instructor and the Multiple Subject Credential Program Coordinator at the time, described:

Residents applied the project approach in their own teaching as they learned about their students’ interests and experiences and tailored content and teaching strategies to be developmentally appropriate. They engaged their students in projects that investigated topics such as the four seasons, community jobs, and cultural traditions around the world to create opportunities for children to engage in active learning and be leaders of their own learning.

Residents also learned to integrate content and skills across disciplines such as mathematics, science, literacy, and visual and performing arts. The interdisciplinary approach is a key component of early learning because children develop in an integrated progression in which development in one area or skill (e.g., memory) can be fundamentally linked to development in other areas (e.g., literacy).Meloy, B., & Schachner, A. (2019). Early childhood essentials: A framework for aligning child skills and educator competencies. Learning Policy Institute. Bennett explained:

The focus was on interdisciplinary integration and knowledge construction and not teaching skills in isolation. I wanted the residents to know theoretically why we did things the way we did in early childhood. It was really important for them to know about how children learn as well as what was developmentally appropriate. (emphasis added)

Integration across content areas was a signature component of the TK–3 program because, in multiple-subject programs, there is typically “no focus on the integration of content across disciplines,” said Bennett. Previously, the literacy foundations course focused on teaching decontextualized skills using mostly fiction, but with the shift to a TK–3 emphasis, residents learned to teach literacy skills within content areas, including how to use informational text as starting points for explorations into science, social studies, or fine arts.

Another early childhood–driven program focus was an emphasis on foundational skills. For example, Bennett encouraged residents to provide multiple opportunities for children to practice and strengthen foundational literacy skills through integrated content. She explained:

We wanted the students to be able to integrate [content] across the disciplines but also to use the units as a springboard for developing foundational literacy skills. Residents infused their lessons with the four components of literacy: . . . reading, writing, listening, and speaking, as well as phonics, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension.

The residents based their instructional lessons on state standards and Fresno Unified’s adopted curriculum, which were used as central texts in their university courses. Residents in TK used the California Preschool Learning Foundations and Curriculum Frameworks as well as the state’s content standards for kindergarten. Guided by these standards, residents also learned to attend to early childhood–specific domains, such as fine motor development, in their lesson planning. All residents collaborated with their mentor teachers to enhance the district curriculum with primary source documents, experiments, and projects to make the curriculum come to life for their students.

District–University Partnership

The early childhood content focus was possible because of the strong partnership between district residency leaders and Fresno State’s teacher preparation program. For every course, Fresno Unified district leaders—typically teachers on special assignment—were paired with university faculty as co-instructors to provide a district lens on how theory and research were enacted throughout the district. Perry explained:

What’s different about Fresno is that all the credential coursework is co-taught. That means there is a faculty member with expertise, and we also have a district co-teacher who’s an expert for us [and who can share] how we practice this within the Fresno Unified context, which is very important when you’re onboarding teachers during preservice instead of waiting for their first year of teaching.

Through quarterly curriculum meetings, district and teacher preparation program leaders designed and implemented the specialized TK–3 residency programming. In these meetings, district leaders collaborated with faculty who had early childhood expertise to redesign courses and assignments to include a developmental focus, emphasizing pedagogy and approaches for children in grades TK through 3, with connections to later development. Perry shared that the curriculum meetings:

were critical to how we designed the program, because we basically took each syllabus and we deconstructed it. We said, “What is it that our candidates need; what are the gaps?” both at the university and the district level. And then [we asked], “How do we support that through instruction?”

The intentionality of weaving in the developmental perspective throughout each course was crucial so that the early childhood focus became a strong common thread across the program.

Benefits for Residents

A major draw for residents, in addition to the early-grade focus, was the $11,000 stipend, made possible through federal TQP grant funds. The stipend was not just a benefit but a necessity for many residents. As program graduate Ezequiel Rodriguez explained:

As a first-generation and low-income student, the [stipend] really stood out to me. [The residency] seemed like it was going to be a full-time commitment, and I knew I wasn’t going to be able to hold [another] job, and if I were to hold a job, it would be very difficult.

Because the stipend was not enough to fully cover their cost of living, some residents also served as a substitute teacher 1 day a week, which allowed them to supplement their income, meet critical substitute teacher shortage needs, and gain valuable clinical experience in other grades.

Another program benefit that attracted residents was that at the end of the 18-month program, residents earned a master’s degree in addition to their teaching credential. With both a credential and master’s degree, residents qualified for higher starting salaries based on the district salary schedule than new teachers hired with a credential only. A major selling point was that rather than simply adding the graduate courses on top of existing credential program courses, district leaders and teacher preparation faculty collaborated to seamlessly integrate the two programs of study within the university degree requirements, with some courses counting toward both the master’s and the credential.

Another benefit was that the residents were clustered together in their school placements, with all courses being held at a school site within a 10-minute drive from residents’ clinical placement sites. Clustering residents together at school sites created place-based peer support networks for the residents. Locating courses within the district cut down on resident commuting and eliminated parking costs. Holding the courses in a school also enabled course instructors to (1) provide feedback on how residents were implementing what they had learned in their coursework into their classroom practice and lesson planning and (2) connect with mentor teachers. As Perry described:

We moved the coursework from the university to the site, and this way, when the faculty were at the school site, they were able to push into our master teacher classrooms. When our residents created these beautiful units, they didn’t just create them for the [university] class. The instructor would push in, observe the instruction, [and] provide feedback.

Benefits for Mentors

Mentor teachers also benefited from participating in the residency. Residents provided consistent and reliable classroom support, enabling more differentiated instruction. Mentor teachers across grades TK through 6 benefited from resident co-teachers. Although the cohorts had an early-grade focus, residents spent some of their clinical hours in upper-grade classrooms within the same school. Mentors also received a small stipend of $700.

In addition, with residency courses occurring at the school site, mentor teachers got the extra benefit of having access to university faculty and their content expertise. Faculty spent time in classrooms not only observing and providing feedback to residents but also modeling lessons and supporting classroom instruction for the mentors. Perry shared, “[We had] buy-in from our teachers at the school site, [who were] saying, ‘Come model for me,’ which was great because now not only were our residents benefiting, but also our master teachers.” Faculty also provided professional development workshops for mentors, particularly in science and math pedagogy.

Mentor teachers and site administrators attributed schoolwide improvements to having two co-teachers in every classroom in combination with faculty support in a high-quality teacher preparation program. Principal Annarita Howell, who hosted an entire cohort of 25 residents at her school site, shared, “Our schoolwide data reflected the positive impact the additional highly trained adults had in student learning, closing the gaps where students struggled.”

Program Outcomes

In just 2 years, between 2017 and 2019, Fresno Unified was able to place 30 new teachers in early-grade classrooms, 10 of which were in TK or kindergarten, with an 83% retention rate as of spring 2022. With such strategic planning, Fresno Unified has been able to fill most of its elementary vacancies in recent years, with its residency program playing a key role in the district’s comprehensive educator pipeline.

Not only has Fresno Unified been able to help adequately staff classrooms through its residency program, but the district has also diversified its teacher workforce. Across the two TK–3 cohorts, 67% of residents identified as candidates of color, compared to 45%Ed-Data. (n.d.). Fresno Unified. (accessed 03/15/22). of teachers in the district in 2018–19, which brought the district closer to reflecting the 90.8% of its students who identified as students of color.California Department of Education. (n.d.). 2018–19 enrollment by ethnicity. DataQuest. (accessed 05/13/22). In addition, both cohorts included recent college graduates as well as older, nontraditional career changers. In order to recruit a diverse candidate pool, the district expanded recruitment efforts beyond the typical career fairs and university-based recruitment events to advertisements in movie theaters, coffee shops, and churches.

The approach of adding a Fresno Unified–specific lens to course content prepared residents to make smooth transitions into their teaching positions. Rodriguez shared that his residency preparation led to stronger self-efficacy and leadership opportunities, even in his first year, which research documents to be notoriously challenging.Ingersoll, R. M., & Smith, T. M. (2003). The wrong solution to the teacher shortage. Educational Leadership, 60(8), 30–33. When describing the difference between his preparation and that of his peers, Rodriguez stated:

One of the biggest differences I experienced in my first year teaching was how smooth a landing I had coming into the classroom. I felt very comfortable and confident in my practice, and it was very nice to see the growth in the students that first year. . . . Also, because I had a smooth landing into my first year, I was asked to take on the role of being the lead teacher, and I mentored a brand-new team of five teachers my first year in.

The focus on early childhood attracted candidates who were passionate about working with young children, like Rodriguez. And that specialized preparation played a critical role in residents’ development. Rodriguez, who teaches 1st grade in Fresno, explained:

I loved coming out of the program because it was an [early childhood education] focus and something that’s going to stick with me forever. I feel that as a practitioner you have to be actively conscious of the age group you are teaching and the importance of developmentally appropriate activities for the students. I learned that children learn through play, so when they’re playing kitchen or when they’re playing teacher, it was an experience that they lived and they’re playing to make sense of it. So I carry that into my practice every day.

The Fresno Teacher Residency Program TK–3 cohort was a cutting-edge program that successfully sought to address the district’s anticipated need for TK and other early-grade teachers with specialized expertise in developmentally appropriate pedagogy. Having met their hiring needs for TK in 2019, Fresno Unified shifted its residency program to focus on special education and STEM in subsequent years. Now, with the expansion of TK, it is planning to relaunch the early childhood focus.

UCLA IMPACT ECE/Multiple Subject Program

The IMPACTIMPACT stands for Inspiring Minds Through a Professional Alliance of Community Teachers. The Power of Urban Teacher Residencies: The Impact of IMPACT. (2014). UCLA Center X. (accessed 04/06/22). urban teacher residency was a social justice–focused program offered through a partnership between Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Center X between 2010 and 2014. IMPACT provided a pathway for candidates interested in early childhood education (ECE) to earn their Child Development Master Teacher Permit, Multiple Subject (elementary) teacher certification, and Master of Education degree, all in 18 months.

The early childhood pathway was launched in 2010 in response to the statewide establishment of TK. Development of the early childhood pathway recognized the unique expertise that teachers need when working with young children. Dr. Helen M. Davis, who directed the IMPACT program, explained, “We would hate for schools to say because we’re preparing kindergarten teachers, we’re well positioned to prepare TK teachers. It’s an easy route, but it’s insufficient [for teachers of younger children].” According to Annamarie Francois, Executive Director of Center X, it is insufficient because “the focus on child and adolescent development is almost absent in some [elementary teacher preparation] programs,” which focus primarily on pedagogy and methods while excluding core early childhood topics like relationship building and family and community engagement. For Hyunja Chung, IMPACT graduate and 3rd-grade teacher, the early childhood focus was a key factor in her interest in the program:

I didn’t see any other grad school programs offering an [early childhood] focus in addition to the master’s and the credential. I enjoy working with younger students, so I thought having a better understanding of childhood development would really make me into a stronger teacher.

Program Approach

The program began with an intense weeklong institute that introduced residents to child development and inclusion content that the program used to frame the residency experience. This institute, combined with the developmental content woven throughout their coursework, helped residents apply a developmental approach to their teaching as they progressed through the program.

Davis explained that “all things [early childhood] begin with understanding child development and how developmental milestones in each domain guide curriculum and planning.” The program started with the courses Child Development and The Child, Family, and Community. These are the first of eight early childhood core courses, often referred to as the CAP 8 in California,The CAP 8 is a set of eight lower-division courses that comprise a 24-unit program of study that can be aligned across community colleges to help ensure consistency in foundational knowledge, skills, and dispositions of early childhood educators. The CAP 8 was developed through the California Community Colleges Curriculum Alignment Project, which also developed the CAP Transitional Kindergarten (CAP TK) to address the specific needs of TK teachers. Child Development Training Consortium. (2022). Curriculum Alignment Project (CAP). (accessed 04/18/22). that residents must complete to fulfill state requirements for the child development permit. Through these courses, residents gained expertise in implementing developmentally appropriate practices as well as in using the California Preschool Learning Foundations and Curriculum Frameworks. In addition, residents learned to use the Desired Results Developmental Profile, an observational assessment prekindergarten teachers use to track individual children’s development. Because residents were working toward two different certifications and a master’s degree, the program required a large number of courses. Looking back, Davis reflected, “A huge value add would be if we could integrate [early childhood education] courses and multiple subject courses to include development in k–8 methods and cut down on the number of separate courses that candidates would have to take.”

Similar to the Fresno program, the early childhood focus was infused in methods courses, particularly literacy methods that prepared residents to use state literacy and English language development standards to teach foundational skills. The course focused on key elements of literacy instruction, including comprehension, fluency, vocabulary, and phonics.Reidell, K., & Anderson-Levitt, K. (2014). Learning to teach language arts in a field in flux. UCLA Center X. (accessed 02/24/22).

The early childhood residents practiced the instructional strategies they learned through extensive clinical experiences over the entire 18-month program, including in early childhood settings serving children birth to 5 years old and in early elementary settings. In their first two quarters, residents had placements in early childhood settings, starting at one of the UCLA campus early care and education centers. These early childhood placements were substantial, requiring residents to be in their assigned classrooms for 6 hours a day, 4 days a week.

In their third and fourth quarters, residents completed clinical placements in two elementary classrooms, working approximately 30 hours per week.During the years in which the IMPACT residency operated, the state required all Multiple Subject candidates to complete student teaching experiences in both a lower elementary (TK–3) and upper elementary (4–8) classroom. This requirement has since changed so that candidates no longer need placements in both grade spans. In all of these placements, residents worked alongside expert mentor teachers who were selected based on effective teaching that incorporated the values and practices of the program, including a teaching approach that acknowledges the role of children’s social and cultural contexts as well as a commitment to social justice. Program faculty advisors intentionally matched mentors and residents based on personality to help ensure a positive clinical experience.Hunter Quartz, K., & the IMPACT Research Group. (2014). Learning in residence: Mixed-methods research on an urban teacher residency program. UCLA Center X. (accessed 03/24/22). In the final stakeholder survey report, one former resident shared that “the field placements were the most meaningful experiences. There is so much I learned from simply being in classrooms, interacting with the children, and working with different mentors.”Dockterman, D. (2014). 2010–15 IMPACT surveys: Cohorts I–IV, final findings. National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, & Student Testing. (accessed 03/24/22); Kawasaki, J., Hunter Quartz, K., & Francois, A. (2014). Multiple measures of mentoring quality: Early lessons from an urban teacher residency program. UCLA Center X. (accessed 03/24/22).

In addition to the focus on developmentally appropriate practice, IMPACT also explicitly focused on developing social justice educators. For Chung, the “focus on social justice and teaching in traditionally underserved communities” were important factors in choosing IMPACT. Residents shared that the program helped them learn to incorporate differentiated instruction, multiple strategies, hands-on approaches, different modalities (e.g., auditory, kinesthetic), and cooperative learning to meet the needs of all students in their classrooms.Center X. (2014). IMPACT Preparing Teachers for Urban Schools: Social Justice (Episode 2) [Documentary series]. UCLA. (accessed 03/09/22). The content and pedagogical strategies that residents learned within this equity framework prepared residents to work in the diverse, traditionally underserved settings where 87% of graduates were hired.This figure is based on data from all residents, not just the ECE cohort, and does not include data from the last (fourth) cohort. Center X. (2014). IMPACT Preparing Teachers for Urban Schools: The Impact of IMPACT (Episode 5) [Documentary series]. UCLA. (accessed 03/09/22). Chung explained that as she transitioned into her own classroom, “I felt very prepared because a lot of the information and trainings provided by the school district professional developments were trainings that were already covered in the residency program.”

Along with child development and equity, a cornerstone of UCLA’s master’s program is inquiry. The focus on inquiry helps to develop the habits of reflecting and questioning as integral to residents’ teaching practice and provides a framework for residents to continually improve their practice throughout their careers. Residents synthesized what they learned about the science of learning and development, teaching methods, and equity-based instructional strategies to investigate questions about their own practice. Residents’ inquiries addressed the puzzles of practice they were experiencing in their clinical placements, including topics such as creating environments in which families feel welcome and comfortable, differentiating instruction, and implementing various classroom management strategies.Dockterman, D. (2014). 2010–15 IMPACT surveys: Cohorts I–IV, final findings. National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, & Student Testing. (accessed 03/24/22).

Benefits for Residents

Several aspects of IMPACT were important in recruiting residents. For Chung, the combination of a yearlong residency in real classrooms with an accelerated timeline for earning multiple credentials and a graduate degree was a no-brainer. “The program had a shorter time frame … and I wanted that additional time in the classroom through a residency program,” she explained. Extensive clinical experience was a crucial factor in how prepared residents felt as they transitioned to their own classrooms.

Other major draws for residents included smaller cohorts and financial supports. Chung described the value of a small, intimate cohort that allowed residents to develop strong relationships with each other. Cohorts for the early childhood program ranged from 9 to 16 residents per year,Dockterman, D. (2014). 2010–15 IMPACT surveys: Cohorts I–IV, final findings. National Center for Research on Evaluation, Standards, & Student Testing. (accessed 03/24/22). and the relationships residents forged were foundational to the resident experience, as they were able to problem-solve, plan, and process learning together.Hunter Quartz, K., & IMPACT Research Group. (2014). Learning in residence: Mixed-methods research on an urban teacher residency program. UCLA Center X. (accessed 03/24/22). Residents also received a $10,000 fellowship, made possible through TQP grant funds, which was very helpful for Chung, who relocated from the Bay Area to enroll in the program.

In addition, residents continued to receive support after program completion. Davis stayed connected to the residents and continued to visit their classrooms throughout their first year beyond the residency, providing additional support and mentoring. Francois shared, “We had not yet created the formal induction program that UCLA currently runs in partnership with the district,” but residency leaders knew that novice teachers still need additional support in their first few years. After the first year, residents continued to have access to field support from UCLA through their third year of teaching.Hunter Quartz, K., & IMPACT Research Group. (2014). Learning in residence: Mixed-methods research on an urban teacher residency program. UCLA Center X. (accessed 03/24/22).

Benefits for Mentors

In addition to intense supports for residents, IMPACT also provided supports for the residents’ mentor teachers, including a stipend of $3,000 and opportunities to grow professionally. Ongoing mentor development was a critical component of the residency program to support mentors in UCLA’s five dimensions of mentoring quality: (1) effective teaching, (2) high-quality feedback, (3) professional learning, (4) professionalism, and (5) strong interpersonal and communication skills.Kawasaki, J., Hunter Quartz, K., & Francois, A. (2014). Multiple measures of mentoring quality: Early lessons from an urban teacher residency program. UCLA Center X. (accessed 03/24/22). A monthly “Methods With Mentors” meeting brought together all the mentors and residents for shared learning around pedagogy and to reflect on their own practice. Mentors also received professional development in cognitive coaching, including how to facilitate resident reflective practice and provide feedback. Araceli Castro, an IMPACT mentor and National Board-certified grade 3 teacher, shared that through Methods With Mentors she has learned:

... how to speak to my [resident], what kind of feedback she’s looking for, and how to be explicit about what I’m doing. A lot of what we do in teaching sometimes feels natural, but there’s theory behind it, and it’s really made me cognizant of what I’m doing and why I’m doing it—classroom management techniques, lesson planning—[so] I’m more aware and able to articulate that to my [resident].Center X. (2014). IMPACT Preparing Teachers for Urban Schools: Mentor Teachers (Episode 4) [Documentary series]. UCLA. (accessed 03/09/22).

These meetings allowed mentors to engage in professional development, develop a shared language, share strategies, and support each other within a professional community. In addition, Carrie Johnson Usui, Director of Professional Development and Partnerships at Center X, explained that Methods With Mentors was a way to not only support mentors but also honor their expertise:

... reinforcing the fact that we value the mentors’ expertise and what they can bring to our [residents], and that it’s not just the faculty advisors who are the ones teaching methods. We really believe the mentors are a critical piece in that, and by bringing them to this Methods With Mentors professional development, that’s highlighting their expertise.Center X. (2014). IMPACT Preparing Teachers for Urban Schools: Mentor Teachers (Episode 4) [Documentary series]. UCLA. (accessed 03/09/22).

Mentors also benefited from co-teaching with residents who “brought in new current ideas that could help the staff grow in ways that routine professional development could not,” shared Davis. According to Davis, hosting residents provided “opportunities for staff to reflect and renew their work and added greatly to the early education programs.”

Program Outcomes

Over four cohorts, the IMPACT program prepared 50 new, fully licensed teachers, 72% of whom identified as teachers of color,Hunter Quartz, K., & IMPACT Research Group. (2014). Learning in residence: Mixed-methods research on an urban teacher residency program. UCLA Center X. (accessed 03/24/22). with expertise in early childhood. Most graduates gained employment in TK to 3rd grade, for which pay is typically higher than in infant/toddler or preschool classrooms, with 87% retained in the district for at least 3 years.This figure is based on data from all residents, not just the ECE cohort, and does not include data from the last (fourth) cohort. Center X. (2014). IMPACT Preparing Teachers for Urban Schools: The Impact of IMPACT (Episode 5) [Documentary series]. UCLA. (accessed 03/09/22). IMPACT teachers have strong performance assessment and teaching evaluation records.Hunter Quartz, K., & Kawasaki, J. (2014). Infographic: The impact of IMPACT. UCLA Center X. (accessed 04/13/22).

The IMPACT program was a forward-thinking innovation that responded to the anticipated need for new teachers to staff TK classrooms. According to Bryan Johnson, Director of Certificated Workforce Management in LAUSD, residency leaders are considering another early grades–focused cohort in their residency expansion plans to meet the need for teachers as TK becomes universal.

Supporting TK Expansion With Teacher Residencies

A growing body of research shows that high-quality residencies are effective pathways that allow more access to teacher preparation for teachers from diverse backgrounds, particularly because they provide financial support to residents.Guha, R., Hyler, M. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The teacher residency: An innovative model for preparing teachers. Learning Policy Institute. Although residencies are typically accelerated 1-year intensive pathways, the programs featured in this brief were both 18 months to allow for master’s-level coursework, with residents eligible to be teachers of record before the end of the program. When used strategically, residency programs can meet district hiring needs with highly qualified teachers who are more likely to stay, develop expertise within the district, help diversify the workforce, and improve the practice of mentor teachers.

Particularly for TK, which will require a 12:1 child-to-adult ratio starting in 2022–23, the residency is a promising model because the resident can be employed, with a salary and benefits, as the second adult in the classroom using assistant teacher or paraprofessional budget lines to cover salary and tuition. This strategy would serve to meet staffing needs with the expansion of TK, fulfill ratio requirements, and provide a paid pathway for new TK teachers to receive robust preparation in meeting the needs of early learners while earning their Multiple Subject (elementary) teaching credential. The residency pathway may be of particular interest to current early childhood educators with a bachelor’s degree working in state preschool programs.

The programs featured in this brief leveraged federal funding through Teacher Quality Partnership grants to launch their TK–3 residencies, which—at $59 million in the fiscal year 2022 budget—continue to be a modest ongoing source of federal support. In the past few years, California has made even more substantial investments than the federal government in building the teacher pipeline, investing more than $2.5 billion in the following grant opportunities that can be leveraged to build a highly qualified TK workforce through residencies.Carver-Thomas, D., Burns, D., Leung, M., & Ondrasek, N. (2022). Teacher shortages during the pandemic: How California districts are responding. Learning Policy Institute.

The Teacher Residency Grant Program funds can be used to plan for, establish, or expand residency programs with a focus on TK or kindergarten.

The Early Education Teacher Development Grant Program provides funds for preparing teachers specifically with early childhood expertise.

The Classified School Employee Teacher Credentialing Program and Educator Effectiveness Block Grant can both support classified school employees, such as paraeducators, in obtaining their elementary teaching certification.

The Golden State Teacher Grant Program provides up to $20,000 directly to candidates enrolled in a teacher preparation program to cover program costs.

With the legislative expansion of TK to serve all 4-year-olds by 2025–26, new child-to-adult ratio requirements, and the approaching 2023 deadline to ensure TK teachers have early childhood expertise, the state will need programs like Fresno Unified’s TK–3 Teacher Residency Program and IMPACT’s early childhood education cohorts over the next few years. Fortunately, the state’s recent investments in teacher residencies and other teacher pipeline programs can help to build and sustain high-quality TK residency programs.

Preparing Transitional Kindergarten to 3rd Grade Educators Through Teacher Residencies by Cathy Yun is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The Learning Policy Institute’s work on teacher preparation is supported by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, W. Clement & Jessie V. Stone Foundation, and the Yellow Chair Foundation. Core operating support for LPI is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the author and not of our funders.