Building a National Early Childhood Education System That Works

To chart a path forward as the nation grapples with the impact of a global pandemic and systemic racism, federal policymakers can advance research-based policies that have been shown to foster equity and opportunity. The Federal Role in Advancing Education Equity and Excellence describes key policies that can help accelerate efforts to ensure that all young people have equal access to a high-quality, world-class education.

Evidence overwhelmingly demonstrates that experiences from birth through age 5 are critical to children’s development. Yet despite the long-term benefits of early childhood education (ECE), many children lack access to integrated, inclusive early learning experiences before kindergarten. Where children do have access to early learning, public investment in program quality is variable and insufficient. Early educators—the key to a successful program—are required to hold widely varying qualifications and are extremely underpaid. Finally, policymakers have often taken an incoherent approach to the governance and administration of ECE programs. These challenges have been glaringly exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has caused many providers to close their doors and threatens the permanent loss of millions of early learning opportunities.

The federal government, along with state and local government, businesses, and communities, shares in the responsibility to provide all children with access to high-quality ECE. The Biden-Harris Platform includes a national plan for addressing the current needs of the field and building an equitable ECE system. Their plan rightly starts with shoring up our current providers to ensure that they remain financially stable through the pandemic. In this whitepaper, we consider the longer-term vision and make the following recommendations, building on this platform and the work of national experts.

Ensure Access to Integrated, Inclusive Programs

- Increase federal support for access to high-quality child care.

- Incentivize and support states in moving toward universal preschool programming in a way that supports socioeconomic, racial, and linguistic diversity.

- Create more seamless alignment between Head Start and state preschool to promote socioeconomically integrated classrooms, without compromising quality.

- Encourage inclusive special education programs that promote continuity of care.

Ensure All Programs Are of High Quality

- Require and provide funding to meet higher levels of quality in subsidized child care programs.

- Require that federally supported preschool programs meet minimum quality standards.

Develop and Support a Well-Qualified Workforce

- Improve early educator compensation.

- Provide financial and academic support to new and current early educators as they move up the career ladder.

- Support institutions of higher education in developing strong ECE preparation programs.

- Ensure access to coaching and other job-embedded supports for all ECE providers.

Build a Coherent, Easily Navigated System of ECE Governance

- Identify and invest in a coordinating strategy to improve the alignment of federal ECE programs and related policies.

- Support comprehensive referral services for families.

- Support comprehensive, publicly available federal and state ECE data collection systems.

Background

Despite widespread public support for ECE programs, the United States has for many years lacked a clear vision for how we as a nation will support children birth through age 5 and to what extent this is a public or private responsibility. The federal government and states have established a range of ECE programs to support the development of young children, but many of these programs are uncoordinated, insufficient in scope, inaccessible, and of variable quality. In turn, funding for ECE represents a remarkably small portion of public spending: less than 0.2% of gross domestic product compared to an average of 0.7% in other economically developed countries.Estimate assumes $19.8 billion in federal spending, $11.5 billion in state spending, and gross domestic product of $18.6 trillion. Note that the federal landscape is changing with federal funding related to COVID-19. Allen, L., & Backes, E. P. (Eds.). (2018). Transforming the Financing of Early Care and Education. National Academies Press; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Social Policy Division. (2019). Public spending on childcare and early education. As a result, many children do not get any formal early learning opportunities before age 5, creating a structural disadvantage from the start that even the best k–12 public schools will struggle to address.Reardon, S. F., & Portilla, X. A. (2016). Recent trends in income, racial, and ethnic school readiness gaps at kindergarten entry. AERA Open, 2(3), 1–18.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further laid bare the fragile state of our ECE programs. Recent closures due to the pandemic have led to financial distress for many programs and families and could mean the loss of up to 4.5 million child care slots nationwide.Jessen-Howard, S., & Workman, S. (2020). Coronavirus pandemic could lead to permanent loss of nearly 4.5 million child care slots. Center for American Progress. State-subsidized ECE programs are likely to take dramatic hits as well if state revenues decline as expected. The federal government, along with state and local governments, businesses, and communities, shares in the responsibility to provide all children with access to high-quality ECE that supports children’s healthy development. In carrying out its responsibility, the federal government should work to address the immediate financial needs of families and providers by providing financial assistance to existing providers to make sure they get through this challenging time. Relief packages passed to date have provided only part of what has been estimated as necessary to stabilize ECE.Estimates suggest that a complete relief package would cost as much as $50 billion; $13.5 billion in new federal spending was allocated in 2020. Ullrich, R., & Sojourner, A. (2020). Child care is key to our economic recovery: What it will take to stabilize the system during the coronavirus crisis. National Women’s Law Center & The Center for Law and Social Policy. P.L. 116-136, Stat. 281 (2020), P.L. 116-260 (2020). Ensuring we maintain a supply of early learning providers and support those who have already been supporting our children is a key first step toward a larger vision.

As we build back our national capacity, however, we must also plan for the future. When building an early learning infrastructure, we must address the four systemic challenges described below that pre-date COVID-19. We consider the full range of publicly supported ECE programs in which children spend their time with a non-familiar caregiver prior to kindergarten entry, including child care (subsidized care for children birth to age 3) and preschool (early learning for children ages 3 to 5).

First, many families lack access to integrated, inclusive ECE programs. The federal government plays an important role in making high-quality programs affordable by subsidizing or paying full tuition for ECE programs for children from low-income families. For example, it funds Head Start and Early Head Start, child care through the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG), early intervention and preschool special education through the Individuals With Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), and Preschool Development Grants for state early childhood system building. (See Appendix 1: Description of Federally Supported ECE Programs.) Yet just 54% of 3- and 4-year-olds in the United States participate in any preschool; just 35% of eligible children participate in Head Start; and only a small fraction of eligible infants and toddlers receive subsidized, licensed child care.Preschool, as defined here and throughout this paper, includes private and public educational programs for children 3–5 years old, including Head Start. Child Trends. (2019). Preschool and prekindergarten (accessed 11/03/20); Child Trends. (2018). Head Start (accessed 11/03/20). Some states are making important strides in offering access to preschool, including five states that serve more than 70% of all 4-year-olds.These include Washington, DC; Vermont; Oklahoma; Florida; and Wisconsin. Friedman-Krauss, A. H., Barnett, W. S., Garver, K. A., Hodges, K. S., Weisenfeld, G. G., & Gardiner, B. A. (2020). The state of preschool 2019. National Institute for Early Education Research. Yet subsidized care is not always directed to the children who need it most, such as children who are homeless or in foster care, due to lack of cohesive policymaking. For those who do have access, many public programs do not meet families’ needs for hours or quality. There are also many children whose families earn just over the income eligibility threshold yet cannot afford the cost of high-quality ECE, which in many states costs more than college tuition.

The ECE system is also highly socioeconomically segregated. Means testing for programs causes children to be sorted, and thus segregated, into classrooms by their family’s income, which, in practice, often translates to racial, ethnic, and linguistic segregation as well.Greenberg, E., & Monarrez, T. (2019). Segregated from the start. Urban Institute; Piazza, P., & Frankenberg, E. (2019). Segregation at an early age: 2019 update. Center for Education and Civil Rights, Penn State College of Education. For example, Head Start and state preschool programs often operate in parallel and serve children in poverty separately from their higher-income peers in state or private preschool programs. Although some schools and community-based organizations blend state preschool and Head Start funding, doing so is difficult due to differences in federal and state standards and reporting requirements. Preschoolers with special needs in state-run programs are also siloed into special education classes even when inclusive general education classes might be the best option because preschool programs are often disconnected from school districts and lack staff with specialized training. This is despite research that shows that inclusive practices and socioeconomic, racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity can have important effects on children’s learning, increasing achievement, especially in the early years.Reid, J. L., Kagan, S. L., Hilton, M., & Potter, H. (2015). A better start: Why classroom diversity matters in early education. Century Foundation and the Poverty & Race Research Action Council; Children’s Equity Project and the Bipartisan Policy Center. (2020). Expanding inclusive learning for children with disabilities: What we know, what we don’t know, and what we should do about it.

Second, quality is variable and insufficient across programs. There is growing consensus that preschool quality matters greatly for children’s outcomes. High-quality programs have several components, including rich interactions between children and adults that are supported by small class sizes and ratios; a developmentally appropriate system of standards, curriculum, and assessment; and a well-qualified workforce, among others.Wechsler, M., Melnick, H., Maier, A., & Bishop, J. (2016). The building blocks of high-quality early childhood education programs. Learning Policy Institute. Yet the nation’s ECE programs vary greatly in their quality standards, and families with lower incomes tend to have access to lower-quality programs.Chaudry, A., Morrissey, T., Weiland, C., & Yoshikawa, H. (2017). Cradle to Kindergarten: A New Plan to Combat Inequality. Russell Sage Foundation. Two federal programs—CCDBG and Head Start—have significant differences in their minimum quality standards and thus contribute to uneven quality at the state level. For example, a 3-year-old receiving a child care subsidy may be in a preschool class with a far less qualified teacher and more children per adult than a child in a Head Start program. Further, most early educators do not have access to coaching and high-quality professional development, despite the fact that both have been shown to improve instructional quality.Landry, S. H., Anthony, J. L., Swank, P. R., & Monseque-Bailey, P. (2009). Effectiveness of comprehensive professional development for teachers of at-risk preschoolers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(2), 448–465; Early, D. M., Maxwell, K., Ponder, B. B., & Pan, Y. (2017). Improving teacher-child interactions: A randomized control trial of Making the Most of Classroom Interactions and My Teaching Partner professional development models. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38, 57–70; Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. Quality rating and improvement systems (QRIS), which have been promoted by federal legislation, have been the main policy lever for raising the quality of care in recent years, yet QRIS funding is low, participation is burdensome, and involvement is voluntary in all but a few states.

Third, educator qualifications requirements are inconsistent and low, and the workforce is chronically underpaid. Having a qualified teacher with specialized knowledge and skills is associated with stronger outcomes for children.Allen, L., & Kelly, B. B. (Eds.). (2015). Transforming the Workforce for Children Birth Through Age 8: A Unifying Foundation. Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. However, ECE programs across the nation struggle to recruit and retain qualified educators due to low wages and challenging working conditions. Child care and preschool educators, who are disproportionately women of color, earn one third to one half of the wages of k–12 educators, and over half rely on public assistance to make ends meet.Whitebook, M., McLean, C., Austin, L. J. E., & Edwards, B. (2018). Early childhood workforce index: 2018. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Federal and state ECE program regulations increasingly require educators to have higher levels of education, but compensation has lagged behind, in part because many early educators lack the ability to collectively bargain.Whitebook, M., & McLean, C. (2017). Educator expectations, qualifications, and earnings. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California; Barnett, W. S., & Kasmin, R. (2016). Funding landscape for preschool with a highly qualified workforce. National Institute for Early Education Research; Battistoni, J. A. (2014). Getting organized: Unionizing home-based child care providers. National Women’s Law Center. This puts a high level of stress on educators, which is passed on to the children they teach and exacerbates turnover, affecting instructional quality.Zinsser, K. M., Christensen, C. G., & Torres, L. (2016). She’s supporting them; who’s supporting her? Preschool center-level social-emotional supports and teacher well-being. Journal of School Psychology, 59, 55–66; Whitebook, M., & Sakai, L. (2001). Turnover begets turnover: An examination of job and occupational instability among child care center staff. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. In addition, early childhood educators who work to increase their qualifications struggle to pay for college and have difficulty completing relevant coursework due to structural barriers.Gardner, M., Melnick, H., Meloy, B., & Barajas, J. (2019). Promising models for preparing a diverse, high-quality early childhood workforce in California. Learning Policy Institute.

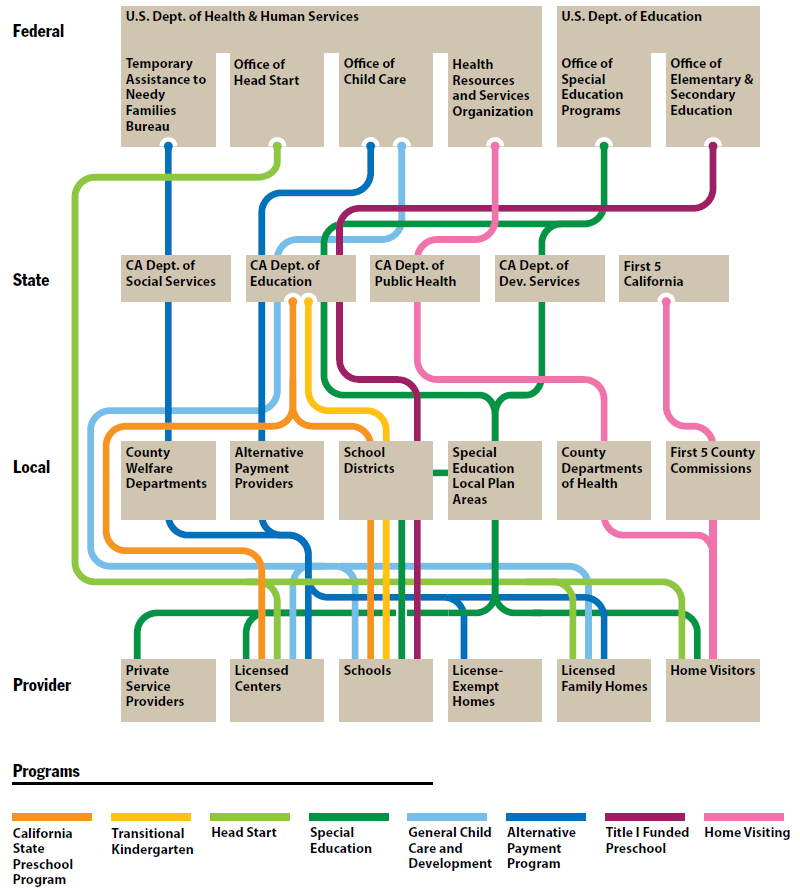

Fourth, governments have taken an incoherent approach to federal and state administration of ECE programs. The current ECE “system” in most states is composed of a patchwork of programs. Multiple federal agencies oversee their administration, including the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Administration for Children and Families and the Department of Education (ED) Office of Special Education and Office of Elementary and Secondary Education. (See Figure 1.) The complexity at the federal level is passed down to state administrators who do not have the capacity or authority to untangle the web of funding and requirements. The system is further complicated by state programs that have their own income eligibility, quality standards, and monitoring. Head Start grantees, for example, have little incentive to participate in state initiatives—a federal-to-local structure that is designed to support and protect underrepresented communities but also adds a challenging level of complexity to the early childhood landscape.Pasachoff, E. (2006). Block grants, early childhood education, and the reauthorization of Head Start: From positional conflict to interest-based agreement. Penn State Law Review, 111(2), 349–411. What is more, special education preschool services are often administered in isolation from other early childhood programs. The incoherence of this fragmented system inhibits efforts to address ECE needs, access, and quality at the federal, state, and local levels.

It is within this context that the Biden-Harris Platform includes a national plan for creating a 21st century caregiving and education workforce. This plan covers many of the essential research-based components of a high-quality ECE system and is in step with comprehensive legislative plans advanced by members of Congress, including the Child Care for Working Families Act (CCWFA). Key components of these plans include high-quality, affordable child care available at no cost for those with low incomes and on a sliding fee scale for others; universally accessible preschool; a fairly compensated, well-prepared workforce; and high-quality standards for early learning. To enhance these programmatic components and support a more efficient, equitable, and stable ECE system that provides a strong start for all children, we recommend the following strategies. Our recommendations build on these plans and many years of work from national experts and ECE stakeholders, including the National Academies of Science reports on financing and the workforce. Our intent is to synthesize and build on these ideas in a way that provides a holistic picture of what it would take to get to an equitable, high-quality early learning system and identify actions the federal government can take, complementing the federal policy suggestions we make for k–12 education. We make recommendations in the following four areas:

- Ensure access to integrated, inclusive programs.

- Ensure all programs are high quality.

- Develop and support a well-qualified workforce.

- Build a coherent, easily navigated system of ECE governance.

Figure 1: Many Federal and State Agencies Oversee ECE Programs

Source: Melnick, H., Ali, T. T., Gardner, M., Maier, A., & Wechsler, M. (2017). Understanding California’s early care and education system. Learning Policy Institute.

Recommendations

I. Ensure Access to Integrated, Inclusive Programs

To support all children’s development, the federal government should incentivize and support state efforts to make preschool universal for 3- and 4-year-olds and provide families of infants and toddlers with access to high-quality, affordable child care. Federal funds should additionally incentivize and support programs that promote socioeconomic, racial/ethnic, and linguistic integration as well as inclusive classrooms that meet the unique needs of children experiencing poverty and children with special needs. Federal policymakers could take the following steps to support access to high-quality, integrated, and inclusive programs:

1. Increase federal support for access to high-quality child care.

The federal government could expand access to affordable child care by increasing funding for child care grants to states. Funding should be sufficient to allow subsidies for all families under 150% of their state’s median income such that no family pays more than 7% of their income. Federal policymakers should also require that when states distribute these funds to programs, payments reflect the true cost of running a high-quality program.Workman, S., & Jessen-Howard, S. (2018). Understanding the true cost of child care for infants and toddlers. Center for American Progress; Allen, L., & Backes, E. (Eds.). (2018). Transforming the Financing of Early Care and Education. National Academies Press.

New child care funding should support stronger ECE infrastructure than our current system, which relies on families paying tuition, only some of which is subsidized, and leaves many publicly supported programs financially unstable. Financial instability is exacerbated by low reimbursement rates as well as attendance-based financing practices that make planning difficult. The federal government could support programs’ financial stability by offering multiyear contracts or grants to programs that serve a minimum number of subsidized children. It could also shift to funding by the number of children enrolled rather than the number of days a child attends. Federal funds could additionally support shared service alliances that help small programs with their finances.Stoney, L. (2020). Reinvent vs. rebuild: Let’s fix the child care system. Opportunities Exchange. By removing the burden of fiscal management and uncertainty, program administrators will be freed up to focus on program quality and instructional leadership.

2. Incentivize and support states in moving toward universal preschool programming in a way that supports socioeconomic, racial, and linguistic diversity.

The federal government could provide sufficient formula funding for states to expand their preschool programs so that, along with a state match, it reaches all children from families who earn at or below a share of the state’s median income (e.g., 150%). A state-match requirement should be reasonable and designed so as not to penalize states that have already made significant investments in preschool.Chaudry, Morrisey, Weiland, & Yoshikawa, for example, suggest an initial federal match of no more than 50% and a long-term federal match of no less than 25%. The Child Care for Working Families Act, by contrast, proposes a continuous 10% state match (i.e., the federal government provides as much as 90% of new funding). Chaudry, A., Morrissey, T., Weiland, C., & Yoshikawa, H. (2017). Cradle to Kindergarten: A New Plan to Combat Inequality. Russell Sage Foundation. These funds should be commensurate with the cost of providing high-quality preschool.Allen, L., & Backes, E. (Eds.). (2018). Transforming the Financing of Early Care and Education. National Academies Press; Chaudry, A., Morrissey, T., Weiland, C., & Yoshikawa, H. (2017). Cradle to Kindergarten: A New Plan to Combat Inequality. Russell Sage Foundation. Formula funds would build on and accelerate the expansion of federal funding for state preschool that began under the Obama Administration through Race to the Top–Early Learning Challenge and the Preschool Development Grants, which states can choose to use in both school- and community-based settings.These competitive grants helped coordinate across programs and agencies to expand access to thousands of children—but due to limited federal funding, increases in preschool access were not sustained. Growth in the percentage of preschoolers served nationwide was 3% from 2008 to 2016, and efforts were primarily focused on children from low-income families. Bornfreund, L., & Lowenberg, D. (2016). The Obama early childhood legacy. New America.

A new federal program could further support socioeconomic diversity by encouraging states to serve all children in a universal program. States could work toward universality in several ways. One way would be to make federal funds contingent upon states gradually moving to universally accessible preschool. The shift to universality could occur over a 10-year period. States that already make large investments in their state preschool programs for children from low-income families could be allowed to shift existing funds toward allowing all 3- and 4-year-olds to access the state’s preschool program, regardless of family income. States could also allow providers to accept private tuition from higher-income families on a sliding fee scale. Alabama offers one example of a mixed funding model: The state requires that districts match state funds, and matching funds may include parent fees paid on a sliding scale, although families may not be denied access based on inability to pay.Alabama Department of Education. (2019). 2019–2020 sliding fee scale for the First Class Pre-K Program. San Francisco has a pilot program that allows moderate-income families who are ineligible for state preschool subsidies to participate in early learning programs on an extended sliding fee scale.San Francisco Office of Early Care and Education. (2018). San Francisco Early Learning Scholarship and Preschool for All Program operating guidelines: Fiscal year 2018–2019.

3. Create more seamless alignment between Head Start and state preschool to promote socioeconomically integrated classrooms, without compromising quality.

As state early learning systems expand, it will be important that state preschool and Head Start funding be leveraged strategically to allow all 3- and 4-year-olds to learn in integrated settings, regardless of family income. To encourage broader access to socioeconomically integrated programs that meet or exceed Head Start quality standards, the federal government could explore ways to increase flexibility of Head Start funding and reporting requirements for contractors or states that show they can serve more preschool-age children while maintaining or exceeding Head Start quality standards. For example, the District of Columbia Public School (DCPS) system worked with its regional Head Start office to allow the district to offer a blended Head Start and district preschool program to all children in Title I schools. This flexibility was granted, with the requirement that DCPS continue to serve at least as many Head Start–eligible children as it did in prior years. The schoolwide model allowed Washington, DC, to more than double the number of children receiving Head Start services, extending Head Start’s reach and creating a more unified system of public preschool for nearly 10 years.DCPS declined to renew its Head Start contract in 2020 for reasons unrelated to the features described in this paper. Garcia, A., & Williams, C. P. (2015). Stories from the nation’s capital: Building instructional supports for dual language learners from prek–3rd grade in Washington, DC. New America; Truong, D. (2020, April 15). D.C. Public Schools lose millions in federal money for Head Start. WAMU 88.5. The federal government could also incentivize states to shift Head Start funding to younger children in Early Head Start in instances for which the state has high levels of preschool attendance and quality. This would alleviate competition between Head Start and state preschool programs and improve access to infant and toddler care. To avoid harming current Head Start grantees serving 3- and 4-year-olds, these providers might instead receive federal preschool funding as described above.

4. Encourage inclusive special education programs that promote continuity of care.

A first step for the federal government to supporting more inclusive early intervention and preschool special education services is to provide adequate federal funding to states to fulfill the IDEA mandate. When Congress passed the first iteration of IDEA in 1975 mandating that all children with disabilities be provided a free and appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment, it also promised that the federal government would provide 40% of the average per-pupil expenditure to help offset the cost of educating eligible students. The federal government has never fulfilled that funding promise and currently funds less than half this amount for preschool-age children.National Council on Disability. (2018). Broken promises: The underfunding of IDEA. As a result, overburdened states and local education agencies place narrow restrictions on eligibility criteria and service hours to meet their IDEA obligations with limited resources.

Additionally, early intervention for infants and toddlers with special needs is administered separately from preschool special education, often by different lead agencies with differing eligibility requirements. Both are disconnected from general education preschool programs. As a result, children and families are more likely to experience disruptions in services when children transition from early intervention and must be referred and reassessed for eligibility for preschool special education. One way the federal government could improve services is by amending the IDEA to align birth-to-age-5 systems. Some states, often referred to as “birth mandate states,” have aligned birth-to-age-5 systems in which all children eligible for IDEA Part C early intervention are automatically eligible at age 3 for the state’s Part B special education and related services—making for more coherent governance and seamless transitions.There are five birth mandate states: Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, and Nebraska. See: Michigan Association of Administrators of Special Education. (2014). Comparing early childhood systems: IDEA early intervention systems in the birth mandate states. Another way the federal government could support a unified special education system is to provide greater assistance and monitoring to ensure that children are offered programs in the least restrictive environment, particularly to ensure that states work toward increasing the proportion of preschool-age children served in mainstream preschool programs. Any new preschool funding could also include a set-aside to support students with special needs in general education classrooms.

II. Ensure All Programs Are of High Quality

Subsidized preschool and child care should meet high-quality state standards, including low adult-child ratios, a high-quality curriculum, well-trained staff, safe facilities, and family supports, that allow them to support nurturing relationships and thoughtful instruction. Evidence is clear that high-quality early learning programs can have profound impacts,Meloy, B., Gardner, M., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). Untangling the evidence on preschool effectiveness: Insights for policymakers. Learning Policy Institute. but many state child care and preschool programs do not require the quality standards that have been shown to be effective. Funding for ECE programs should, in turn, be commensurate with what it costs to provide high-quality ECE in all settings, including schools, centers, and home-based care. Currently, most providers lack access to the support they need to improve their quality, including coaching and paid planning time. Federal policymakers could take the following steps to support quality improvement:

5. Require and provide funding to meet higher levels of quality in subsidized child care programs.

National studies show that programs do not have the resources and staffing they need to provide quality learning environments, especially in programs serving children from low-income backgrounds and in family child care and unlicensed settings.Chaudry, A., Morrissey, T., Weiland, C., & Yoshikawa, H. (2017). Cradle to Kindergarten: A New Plan to Combat Inequality. Russell Sage Foundation. One way to raise quality would be for the federal government to set higher health and safety regulations under CCDBG and fund programs accordingly. Current regulations are minimal—for example, states set their own standards for group size, staff-to-child ratios, and staff qualifications—and a curriculum is not required. The federal government should raise CCDBG quality standards to include a minimum standard for group size and adult-child ratios and minimum teacher qualifications and should require that programs use a developmentally appropriate curriculum. Child care funding should be significantly increased to ensure that programs receive adequate funding to meet these standards and for quality improvement activities, such as coaching and paid planning time. As states raise their quality standards, they should integrate state licensing and QRIS standards to reduce the burden on providers and increase efficiency so that providers would not need to be monitored and evaluated both by QRIS assessors and the state licensing agency.

6. Require that federally supported preschool programs meet minimum quality standards.

New federal funding for preschool programs could require that investments be made in programs that meet the quality standards laid out in the Preschool Development Grant program. Required program characteristics include teachers having at least a B.A. in ECE, salary parity with local schools, staff-to-child ratios of no more than 10 to 1, use of a developmentally appropriate curriculum, and a duration of at least a full school day. Given that these standards are substantially higher than most state preschool programs,Friedman-Krauss, A. H., Barnett, W. S., Garver, K. A., Hodges, K. S., Weisenfeld, G. G., & Gardiner, B. A. (2020). The state of preschool 2019. National Institute for Early Education Research. the new federal program might allow states to use initial federal funding to increase the quality of their current preschool programs.

III. Develop and Support a Well-Qualified Workforce

Well-prepared educators are the most important part of an early learning program. Given that the current workforce is already dramatically under-compensated for the job demands, increased pay and benefits are critical components to supporting educator quality. At the same time, federal policy should support the professionalization of the workforce by helping states to increase the number of credentialed teachers with a specialization in ECE. Federal policy should therefore support states’ efforts to improve the qualifications and compensation of the ECE workforce. Federal policymakers should take the following steps to develop and support a well-qualified ECE workforce:

7. Improve early educator compensation.

Adequate compensation for the early learning workforce is a critical component to ensuring the success of ECE programs. While the federal government has a limited role in directly addressing locally set salaries, one key lever is providing adequate funding for CCDBG that will allow states to reimburse programs for the true cost of care, including better compensation. In addition, there are several ways that federal policymakers can support equitable compensation. One way is through QRIS. States receiving federal funds could be required to include salary and benefit standards in their QRIS, with the lowest compensation level being a living wage and the highest level being parity with public school teachers. The federal government can also fund Head Start at a level that allows educators to be paid at parity with kindergarten teachers in local public schools. Head Start teachers currently earn an average of $33,000 a year, compared to an average of $57,000 annually for elementary school teachers.Data are for the 2014–15 school year. Barnett, W. S., & Friedman-Krauss, A. H. (2016). State(s) of Head Start. National Institute for Early Education Research. Finally, as part of a strategy to ensure p–12 educators are adequately compensated, the federal government could develop an income tax credit for educators serving in the highest-poverty schools, in which all ECE educators receive the highest credit available. (See the Federal Role in Advancing Education Equity and Excellence.)

8. Provide financial and academic support to new and current early educators as they move up the career ladder.

One way the federal government can support early educators attaining higher credentials and degrees is by creating a dedicated federal scholarship program to provide academic and financial support to ECE educators, which would supplement current need-based financial aid. This program could provide service scholarships that underwrite the cost of higher education for early educators who commit to working in subsidized programs for 2–4 years. Federal funds could also support the development of registered apprenticeship programs, a promising model for current and aspiring educators, leveraging funding from the Department of Labor.Guarino, A. (2019). Strengthening the early learning field with registered apprenticeships. First Five Years Fund; Petig, A. C., Chavez, R., & Austin, L. J. E. (2019). Strengthening the knowledge, skills, and professional identity of early educators: The impact of the California SEIU Early Educator Apprenticeship Program. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Since many students in ECE programs are nontraditional students returning to the classroom after many years, and many are English learners, the program could provide participants with academic assistance and advising to help navigate the higher education system.

9. Support institutions of higher education in developing strong ECE preparation programs.

Another way the federal government could develop a better-trained ECE workforce is to establish a new grant program to support ECE and child development programs at institutions of higher education. Grant funds could be used to improve degree programs at 2- and 4-year colleges as well as credentialing programs that are focused on preparing ECE educators for the classroom. The grant program could support practice-based learning by developing guided pathways and capacity building, such as hiring and training well-qualified, diverse faculty. Funds could also be used to support flexible scheduling and the provision of courses in alternative locations to make coursework accessible to more students. Finally, some portion of funds might be set aside for developing graduate programs in early learning to support the development of educators and instructional leaders with expertise in ECE.

10. Ensure access to coaching and other job-embedded supports for all ECE providers.

Coaching—direct observation paired with individualized feedback from a mentor—has been linked to improved child-teacher interactions, less teacher burnout, and increased teacher retention.Aikens, N. & Akers. (2011). Background review of existing literature on coaching. Mathematica Policy Research; Boller, K., Del Grosso, P., Blair, R., Jolly, Y., Fortson, K., Paulsell, D., Lundquist, E., Hallgren, K., & Kovac, M. (2010). Seeds to Success Modified Field Test: Findings from the impact and implementation studies. Mathematica Policy Research; O’Keefe, B. (2017). Primetime for coaching: Improving instructional coaching in early education. Bellwether Education Partners. Coaching is currently an allowable use of funds in CCDBG and is a particularly high-leverage strategy for quality improvement. Compared to other quality improvement activities, however, it is costly. The federal government could consider creating a set-aside within CCDBG dedicated to supporting high-quality coaching in all classrooms. Funding could go to programs that meet research-based program design standards, including for coaching frequency and coach qualifications.

IV. Build a Coherent, Easily Navigated System of ECE Governance

The existence of multiple programs run by several agencies has created a siloed approach to policymaking and funding. This prevents policymakers from having a comprehensive understanding of who is being served and how, where gaps exist and for whom, and even how much the federal government and states are investing in ECE overall. An administrative structure that supports stability and allows policymakers to see the whole system could enable more informed decisions. Federal policymakers should take the following steps to support early learning systems that are cohesive and easy for providers and parents to navigate:

11. Identify and invest in a coordinating strategy to improve the alignment of federal ECE programs and related policies.

The strategy should address strengthening alignment within and between federal, state, and local agencies that fund and administer ECE programs; streamlining and integrating programs that are currently fragmented; establishing an information clearinghouse; and overseeing ECE data, information systems, and reporting. The coordinating strategy might include a Children’s Cabinet or a renewed interagency policy board, similar to the Interagency Policy Board created in 2010 to advise the secretaries of ED and HHS on how to align and coordinate services for children birth to age 8. The board included senior staff from both ED and HHS, the White House Domestic Policy Council, and the Office of Management and Budget. It issued joint policy statements and coordinated activities that crossed programs, such as the Preschool Development Grants and Early Head Start–Child Care Partnerships.U.S. Department of Education and Department of Health and Human Services. (2017). Early Learning Interagency Policy Board (IPB) report to the Secretaries of Education and Health and Human Services. The coordinating strategy could also reinstate and strengthen the Office of Early Learning in ED that was created by the Obama Administration, which had a deputy assistant secretary that worked closely with a counterpart at HHS. This office could play a role in administering preschool funding and support p–3 alignment. Any coordinating entity would need to be well staffed and funded and granted sufficient authority to do its job well.

12. Support comprehensive referral services for families.

Resource and referral services, which help families identify and pay for child care, are currently funded by CCDBG but could be improved. For example, the federal government could provide one-time funding to state agencies to collaborate with local partners and develop a single, statewide application for families to show eligibility for state and federal ECE programs, including child care subsidies, Head Start, state preschool, and other programs serving children and families. It could also provide funding to states to develop unified waitlists across agencies that help administrators prioritize enrollment and provide parents information about real-time availability of child care.

13. Support comprehensive, publicly available federal and state ECE data.

Programs that rely on several funding streams should not have to report data multiple times, and states should have access to comprehensive data on their programs in one place. The federal government could streamline collection and reporting of data for federal ECE programs, including special education services, Head Start, and CCDBG, by providing funding to support these efforts. Federal policymakers could increase funding and technical assistance for the development of data collection procedures that provide unified reporting on states’ ECE availability and quality, including the racial/ethnic and socioeconomic concentration of children within and across programs as well as the compensation and qualifications of the workforce, disaggregated by race and ethnicity. States’ multiple early childhood data systems should be integrated with each other and with k–12 data to be able to answer important policy questions, such as how access varies by child characteristics.

Conclusion

High-quality ECE can put children on the path to success in school and in life. But many U.S. children do not have access to ECE, and not all programs are integrated and high quality. The patchwork of underfunded programs and services available to young children and their families is incoherent and insufficient. Federal policymakers have a number of tools and resources at their disposal to support state and local efforts to meet the needs of children and families so that each piece of the system is of high quality and part of a coherent system. Model practices exist in many states, and it is time for the federal government to build on these successes. Increasing access and improving quality and diversity will require both significant budgetary and operational attention, but ultimately can create a system that, as a whole, will better serve our children.

See Appendix 1: Description of Federally Funded ECE Programs.

Building a National Early Childhood Education System That Works is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.