How Effective Are Loan Forgiveness and Service Scholarships for Recruiting Teachers?

Summary

Recruiting and retaining talented individuals into the teaching workforce, especially in schools in underserved urban and rural communities, is challenging when college graduates face more lucrative professional alternatives and often carry significant student debt. Two promising approaches to attracting and keeping teachers in the profession are to offer loan forgiveness or service scholarships to prospective teachers—similar to what the medical profession has used to attract practitioners into underserved communities. Existing research on teacher and physician loan forgiveness and service scholarship programs suggests that, when the financial benefit meaningfully offsets the cost of professional preparation, these programs can successfully recruit and retain high-quality professionals into fields and communities where they are most needed.

Introduction

Teacher shortages pose a recurring problem in American education. Teacher salaries lag behind those of other occupations that require a college degree, and young people often accrue significant debt to prepare for the profession. Recruitment and retention challenges are typically greatest in underserved urban and rural communities, as well as in subjects like math, science, and special education in which people can earn significantly higher starting salaries in private sector jobs. Even after adjusting for the shorter work year, beginning teachers nationally earn about 20% less than individuals with college degrees who enter other fields, a gap that widens to 30% by mid-career.Bruce D. Baker, David G. Sciarra, and Danielle Farrie, “Is School Funding Fair? A National Report Card,” (2015): 28. Compounding this challenge, more than two-thirds of those entering the education field borrow money to pay for their higher education, resulting in an average debt of $20,000 for those with a bachelor’s degree and $50,000 for those with a master’s degree.Sandra Staklis and Robin Henke, “Who Considers Teaching and Who Teaches?,” U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics (November 2013): 13; U.S. Department of Education, “Web Tables: Trends in Graduate Student Financing: Selected Years, 1995–96 to 2011–12,” (2015). College loans represent a significant debt burden for many prospective teachers and a potential disincentive to enter the profession.Baker, Sciarra, and Farrie, “Is School Funding Fair? A National Report Card.”

As in other professions, such as medicine, a promising approach to attracting and keeping teachers in the profession involves offering subsidies for preparation—loan forgiveness or service scholarships—tied to requirements for service in high-need fields or locations. If recipients do not complete their service commitment, they must repay a portion of the scholarship or loan, sometimes with interest and penalties.

The federal government and the states have long offered such incentives to medical professionals to fill needed positions and have periodically done so for teachers as well.Such incentives have also been available to public interest lawyers, often provided by law schools. NYU Law School’s Innovative Financial Aid Study, which randomly assigned applicants to various financial aid packages and debt structures with equivalent net values, found that law students who received scholarships (as opposed to loan forgiveness) had a 37% higher likelihood of their first job being in public interest law, and also appeared to be of a higher quality. See Erica Field, “Educational Debt Burden and Career Choice: Evidence from a Financial Aid Experiment at NYU Law School,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1, no. 1 (2009): 1. In both medicine and teaching, research suggests that these programs have been successful when the subsidies are large enough to substantially offset training costs. More affordable than across-the-board salary increases, loan forgiveness and scholarship programs offer a targeted, short-term approach to increasing teachers’ overall compensation package at the time that it matters most to individuals’ career decisions.See, e.g., Frank Adamson and Linda Darling-Hammond, “Speaking of Salaries: What It Will Take to Get Qualified, Effective Teachers in All Communities,” Center for American Progress, (2011): 7.

Loan Forgiveness & Service Scholarship Programs in Medicine

Multiple studies have found that loan forgiveness and service scholarship programs are effective at recruiting and retaining healthcare professionals into geographic and practice areas with shortages. An analysis of 43 studies exploring the effectiveness of financial incentive programs in recruiting and retaining healthcare workers in underserved areas found that financial incentives (including service scholarships, loan forgiveness, and loan repayment programs) contributed to large numbers of healthcare workers working in underserved areas.Till Bärnighausen and David E. Bloom, “Financial Incentives for Return of Service in Underserved Areas: A Systematic Review,” BMC Health Services Research 9 (2009). In addition, participants in these programs were more likely than non-participants to work in underserved areas in the long run.Ibid. One study of state loan repayment programs and service scholarships for physicians who committed to work in underserved communities for a designated period of time found that 93% of participants completed their commitment, and approximately two-thirds remained in these communities for more than eight years.Donald E. Pathman et al., “Outcomes of States’ Scholarship, Loan Repayment, and Related Programs for Physicians,” Medical Care 42, no. 6 (2004): 560–68. Another study of 229 medical students found that students who were more competitive at the time of their admission to medical school were more likely to say that they would be less likely to accept a service scholarship if it contained a penalty provision.John Bernard Miller and Robert A. Crittenden, “The Effects of Payback and Loan Repayment Programs on Medical Student Career Plans,” Journal of Rural Health 17, no. 3 (2001): 160–64. In addition, 48% said they would be more likely to return to an underserved community in their home state if they received loan forgiveness to do so.Ibid.

Loan Forgiveness & Service Scholarship Programs for Teachers

The federal government and more than 40 states offer loan forgiveness and/or service scholarship programs to individuals interested in teaching.Li Feng and Tim R. Sass, “The Impact of Incentives to Recruit and Retain Teachers in ‘Hard-to-Staff’ Subjects,” Working Paper 141, National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research (2015). These programs are typically smaller and less consistently available than those for the medical profession. Nonetheless, the research that exists indicates that well-designed programs can influence the recruitment and retention of talented teachers in high-need areas and locations.

The more debt college students incur, the less likely they are to choose to work in a lower-wage profession. A recent study of students at a highly selective undergraduate institution found that incurring debt increased the odds that students chose “substantially higher-salary jobs” and “reduce[d] the probability that students [chose] low-paid ‘public interest’ jobs.” The influence of debt on job choice was “most notable on the propensity to work in the education industry.”Jesse Rothstein and Cecilia Elena Rouse, “Constrained after College: Student Loans and Early-Career Occupational Choices,” Journal of Public Economics 95, no. 1–2 (2011): 149–63. In other words, the top-performing students were more likely to pursue a career in education when they did not have a large debt. Other research has found that minority students and students from low-income households perceive student loans as a greater burden than other students with similar student debt earning similar salaries.Sandy Baum and Marie O’Malley, “College on Credit: How Borrowers Perceive Their Education Debt,” Journal of Student Financial Aid 33, no. 3 (2003): 7–19. This research suggests that loan forgiveness and service scholarships may be especially effective for recruiting teacher candidates from low-income and minority backgrounds.

Research on loan forgiveness and service scholarship programs for teachers has found these programs are effective at attracting individuals into the teaching profession and particularly into high-need schools. For example, the National Science Foundation Robert Noyce Teacher Scholarship provides scholarships for prospective teachers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics who commit to teach in high-need schools for at least two years per each year of funding. A 2007 survey of 555 recipients found that 56% of recipients identified the scholarship as influential in their decision to complete a teacher certification program. Approximately 70% of recipients noted that the scholarship influenced their commitment to teach in a high-need school and remain in such a school for the full term of their commitment.Pey Yan Liou, Allison Kirchhoff, and Frances Lawrenz, “Perceived Effects of Scholarships on STEM Majors’ Commitment to Teaching in High Need Schools,” Journal of Science Teacher Education 21, no. 4 (2010): 451–70. The higher the percentage of tuition covered by the scholarship, the greater the influence the funding had on the recipients’ decisions to become teachers and to teach in high-need schools.Pey-Yan Liou and Frances Lawrenz, “Optimizing Teacher Preparation Loan Forgiveness Programs: Variables Related to Perceived Influence,” Science Education Policy 95, no. 1 (2011): 139.

A study of the Woodrow Wilson Fellowship program found that its recipients were more likely to teach students in high-need schools and more effective teachers. The program provides a one-year $30,000 service scholarship to high-achieving candidates who complete a master’s degree program in a STEM-focused teacher preparation program and commit to teach in a high-need school for three years. Based on data from the first year of the program in Michigan, the study found that recipients were two times more likely to teach low-income students and three times more likely to teach English language learners, as compared to non-fellows. The study also found that in Indiana, which had multiple years of data, recipients were more effective than both experienced and inexperienced non-recipients at raising minority students’ test scores in middle-school math, middle-school science, and algebra. Recipients were also almost twice as likely to persist in Indiana’s public high-needs schools as compared to non-recipients.The study’s findings are from an independent external assessment performed by the Center for the Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research at the American Institute of Research, as reported in Woodrow Wilson Foundation, “Answering the Call for Equitable Access to Effective Teachers: Lessons Learned From State-Based Teacher Preparation Efforts in Georgia, Indiana, Michigan, New Jersey, and Ohio,” The Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation (Princeton, NJ: 2015).

A study of California’s Governor’s Teaching Fellowship (GTF) program, which also looked at participants in California’s Assumption Program of Loans for Education (APLE) loan forgiveness program, found that both programs had attracted teachers to low-performing schools and kept them in these schools at rates higher than the state average retention rate, despite such schools usually having much higher attrition.The retention rate of the state-subsidized teachers was 75% in disadvantaged schools. (See Jennifer L. Steele, Richard J. Murnane, and John B. Willett, “Do Financial Incentives Help Low-Performing Schools Attract and Keep Academically Talented Teachers? Evidence from California,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 29, no. 3 (2010): 451–78.) Meanwhile, the overall teacher retention rate for teachers with five years of experience was found to be about 74% in a statewide study around the same point in time. (See Deborah Reed, Kim S. Rueben, and Elisa Barbour, Retention of New Teachers in California (San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California, 2006)). In exchange for teaching at least four years in a low-performing school, APLE provided loan forgiveness of $11,000 to $19,000, while the GTF provided $20,000 scholarships to a more selective group of prospective teachers.California Student Aid Commission, “2006-07 Annual Report to the Legislature” (California Student Aid Commission, 2007). The authors of the study suggest that the GTF recipients “had weaker predispositions” to teach in low-performing schools than the non-recipients in their study (i.e., individuals who only received APLE loan forgiveness), and that about two of every seven fellowship recipients would not have taught in such schools in the absence of the incentive.Jennifer L. Steele, Richard J. Murnane, and John B. Willett, “Do Financial Incentives Help Low-Performing Schools Attract and Keep Academically Talented Teachers? Evidence from California,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 29, no. 3 (2010): 451–78.

In 2003, the Illinois Student Assistance Commission conducted a study of the state’s two loan forgiveness programs that provided $5,000 for each year of postsecondary schooling in exchange for a one-year teaching commitment per each year of subsidy. It found that, of the 1,167 recipients who had passed the grace period of loan deferment, 86% were repaying or had repaid their loans through teaching and 14% were pursuing other careers. Of those who received and accepted teaching positions after graduation, 43% indicated the program was very influential in their decision to become a teacher.Illinois Student Assistance Commission, “Recruiting Teachers Using Student Financial Aid: Do Scholarship Repayment Programs Work?,” (Deerfield, IL: Illinois Student Assistance Commission, 2003).

Additional research suggests that loan forgiveness and scholarship programs also attract high-quality individuals to the teaching profession. A survey of 400 National and State Teachers of the Year found that 75% and 64% of the teachers said that “scholarship programs for education students” and “student loan forgiveness programs” were the most effective recruitment strategies for new teachers, respectively.Phyllis E. Goldberg and Karen M. Proctor, “Teacher Voices” (Scholastic/CCSSO Teacher Voices Survey, 2000): 6.

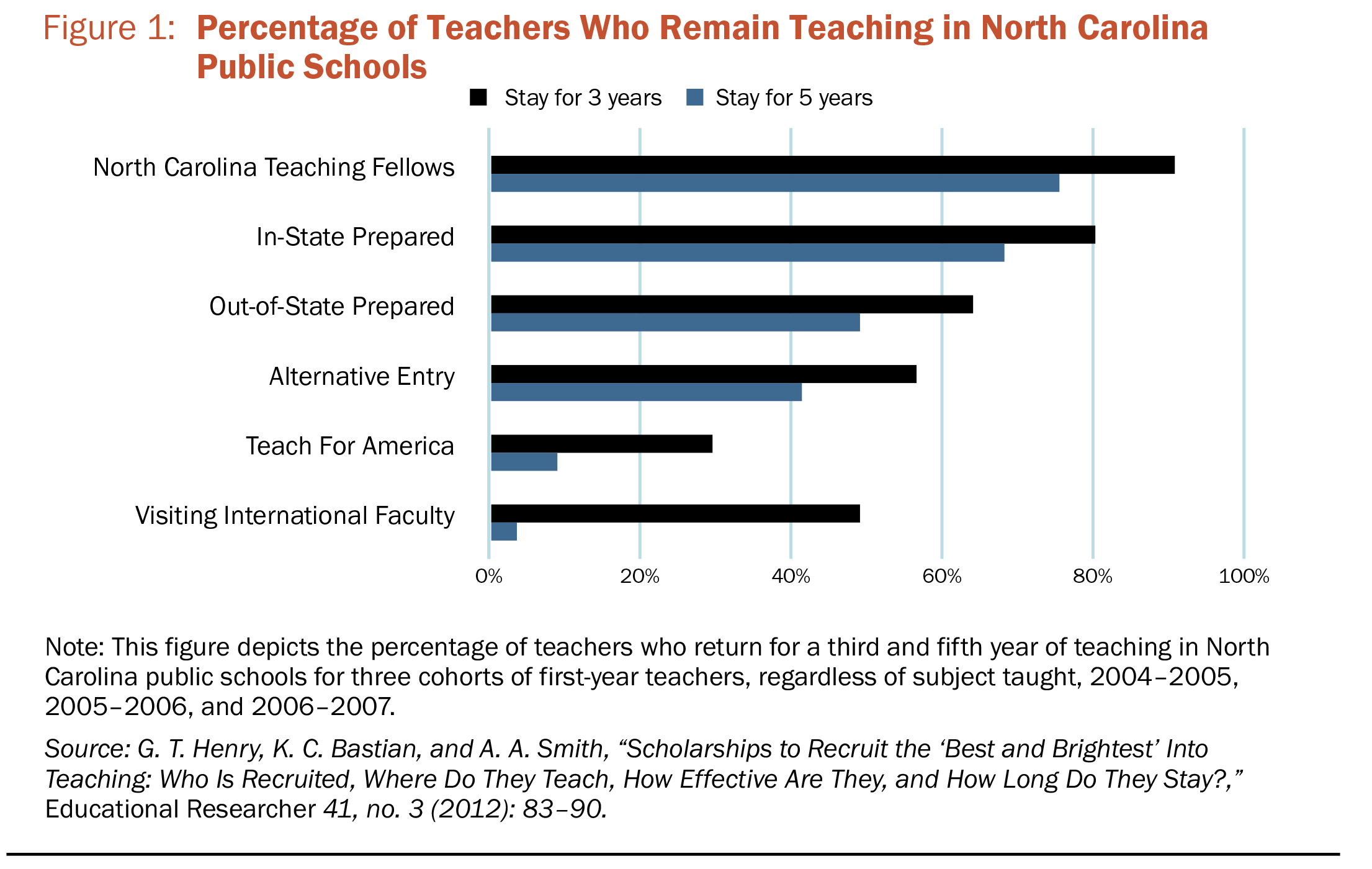

A longitudinal study of the North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program (see below)—a long-standing scholarship program that recruited high-ability high school graduates and provided them an enhanced teacher preparation program in exchange for a commitment to teach for at least four years in the state—found that these fellows not only had higher rates of retention, but they were also generally more effective educators than their peer teachers as measured by test score gains of their students.Gary T. Henry, Kevin C. Bastian, and Adrienne A. Smith, “Scholarships to Recruit the ‘Best and Brightest’ Into Teaching: Who Is Recruited, Where Do They Teach, How Effective Are They, and How Long Do They Stay?,” Educational Researcher 41, no. 3 (2012): 83–92. As shown in Figure 1, more than 90% of Teaching Fellows returned for a third year, and 75% returned for a fifth year, as compared to other in-state prepared teachers (80% and 68% respectively).Ibid at 90.

The North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program

The North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program “aimed to create a pipeline of exceptional teacher-leaders for public schools throughout the state.”1 To do this, the program provided scholarships of $6,500 annually for four years to high-ability high school students to attend one of 12 public and five private in-state universities to participate in an enhanced teacher preparation program.2 From 1986 to 2015, the program recruited nearly 11,000 candidates into teaching, representing approximately 10% of all North Carolina teachers credentialed each year.3 In return, fellows committed to teaching in North Carolina public schools for four years. If fellows did not complete their commitment, their scholarship converted to a loan with 10% interest.

Fellows applied as high school seniors through a highly selective process that included a review of grades and test scores, a detailed application, essays, nominations from their guidance counselors, and multiple interviews. Only one in five were selected. A disproportionate number were men and teachers of color, both typically underrepresented in the teaching force.4 Once admitted, fellows ranked their desired North Carolina university and were awarded a scholarship depending on acceptance from the university.

As undergraduate students, fellows’ identities as teachers were cultivated early on. In addition to receiving the same teacher preparation coursework and clinical training as other teacher preparation candidates, beginning freshman year fellows participated in such enrichment activities as tutoring and field experiences in public schools, summer retreats, and seminars on pedagogy and professional development.

In the 2013–14 school year, more than 4,600 fellows were teaching in public schools in all 100 counties in North Carolina. Many fellows have gone on to become principals and superintendents in the state.5 Mount Airy City Schools Superintendent Greg Little says the scholarship “allowed me to go to college and not have crippling student loans. I became a superintendent in large part because I did not have crippling school loans that precluded me from pursuing my master’s degree and doctorate.”6

1. Todd Cohen, “A Legacy of Inspired Educators” (North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program, 2015).

2. See Cohen, “A Legacy of Inspired Educators.” See also Barnett Berry, Keeping Talented Teachers: Lessons learned from the North Carolina teaching fellows, North Carolina Teaching Fellows Commission (1995).

3. U.S. Department of Education, “North Carolina, Section I.g Teachers Credentialed,” Title II Higher Education Act, accessed October 29, 2015.

4. Henry, Bastian, and Smith, “Scholarships to Recruit the ‘Best and Brightest’ Into Teaching: Who Is Recruited, Where Do They Teach, How Effective Are They, and How Long Do They Stay?”

5. Cohen, “A Legacy of Inspired Educators.”

6. Cohen, “A Legacy of Inspired Educators.”

A recent study of the Florida Critical Teacher Shortage Program (FCTSP) suggests that loan forgiveness payments to teachers in hard-to-staff subject areas contribute to their decisions to stay in the profession, as long as they are receiving the financial stipend.Feng and Sass, “The Impact of Incentives to Recruit and Retain Teachers in ‘Hard-to-Staff’ Subjects.” The FCTSP provided loan forgiveness of $2,500 per year to undergraduates and $5,000 per year to graduates, up to $10,000. The study found that loan forgiveness “significantly reduces the probability of exit” for teachers of middle- and high-school math and science, foreign language, and English as a Second Language.Ibid.

While numerous studies have found that loan forgiveness or service scholarship programs covering a significant portion of tuition and/or living costs are effective in recruiting teachers into the profession and especially into high-need schools and fields, some studies have found that programs that provide small amounts are not effective. A study of the Arkansas State Teacher Education Program suggests that the small amount of money—on average $3,000 per year—provided to teachers who taught in high-need districts was too low to attract teachers given the much higher salaries in nearby districts.Robert Maranto and James V. Shuls, “How Do We Get Them on the Farm? Efforts to Improve Rural Teacher Recruitment and Retention in Arkansas,” Rural Educator 34, no. 1 (2012): n1. In another study, 82% of surveyed recipients of Oklahoma Future Scholarships, which range from $1,000 to $1,500, reported that they would have gone into teaching science (the focus of the scholarship) even without the scholarship.Kay S. Bull, Steve Marks, and B. Keith Salyer, “Future Teacher Scholarship Programs for Science Education: Rationale for Teaching in Perceived High-Need Areas,” Journal of Science Education and Technology 3, no. 1 (1994): 71–76. Again, the small amount of the scholarship suggests that minor financial stipends do little to attract individuals into teaching in hard-to-staff schools and subjects who would not otherwise be interested.

A U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) study of federal grant and loan forgiveness programs for teachers suggests that how a program is structured also influences its success. In reviewing the TEACH grant program, which provides up to $16,000 in grants to prospective teachers who agree to teach in a low-income school and high-need subject area for four years, the GAO found that one-third of TEACH grant recipients did not fulfill the grant requirements. Instead, their grants were converted to unsubsidized federal loans, with high levels of interest accrued over several years. The GAO criticized the program’s design and management, including the requirement that participants submit burdensome annual paperwork as well as an ineffective appeals process for recipients whose grants had been erroneously converted to loans.United States Government Accountability Office, “Better Management of Federal Grant and Loan Forgiveness Programs for Teachers Needed to Improve Participant Outcomes,” (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Accountability Office, 2015).

Conclusion

Existing research on teacher loan forgiveness and service scholarship programs suggests that, when the financial benefit meaningfully offsets the cost of a teacher’s professional preparation, these programs can be successful in both recruiting and retaining teachers. Research suggests that the following five design principles could guide the development of loan forgiveness and service scholarship programs:

- Covers all or a large percentage of tuition.

- Targets high-need fields and/or schools.

- Recruits and selects candidates who are academically strong, committed to teaching, and well-prepared.Linda Darling-Hammond and Gary Sykes, “Wanted: A National Teacher Supply Policy for Education: The Right Way to Meet the ‘Highly Qualified Teacher’ Challenge,” Education Policy Analysis Archives 11, no. 33 (2003): 1–55; Christopher Day, Bob Elliot, and Alison Kington, “Reform, Standards and Teacher Identity: Challenges of Sustaining Commitment,” Teaching and Teacher Education 21, no. 5 (2005): 563–77.

- Commits recipients to teach with reasonable financial consequences if recipients do not fulfill the commitment (but not so punitive that they avoid the scholarship entirely).Many programs provide for leaves of absences or non-consecutive commitments if recipients experience serious illness, military service, pregnancy, other unexpected causes, or reassignments to teaching positions that are beyond their control. Research also suggests that financial consequences for not fulfilling the commitments associated with service scholarships should not be so punitive that recipients avoid the scholarship entirely. Donald E. Pathman, “What Outcomes Should We Expect from Programs that Pay Physicians’ Training Expenses in Exchange for Service,” NC Med J 67, no.1 (2006): 77–82.

- Bureaucratically manageable for participating teachers, districts, and higher education institutions.

Importantly, research finds that these programs are effective at attracting strong teachers into the profession generally and into high-need schools and fields in particular. Research also finds that these programs are successful in promoting teacher retention. Teacher loan forgiveness and service scholarship programs provide states and districts with options for addressing the high rate of attrition at disadvantaged schools that occurs when schools must recruit candidates without the preparation or incentives that would strengthen their commitment.See, e.g., David M. Miller, Mary T. Brownell, and Stephen W. Smith, “Factors that predict teachers staying in, leaving, or transferring from the special education classroom,” Exceptional Children 65, no. 2 (1999): 201-218; Erling E. Boe, Lynne H. Cooke, and Robert J. Sunderland, “Attrition of Beginning Teachers: Does Teacher Preparation Matter?,” Research Report No. 2006-TSDQ2 (Philadelphia, PA: Center for Research and Evaluation in Social Policy, Graduate School of Education, University of Philadelphia, 2006).

Loan Forgiveness: One Teacher’s Story

After spending a summer in college teaching low-income students in San Jose, CA, Irene Castillon knew she wanted to work to improve educational opportunities in under-resourced communities. As the first in her family to graduate high school, Castillon understood from personal experience the role education plays in creating pathways to opportunity. Without a service scholarship and a forgivable loan, the cost of a teacher preparation program would have been prohibitive, and Castillon—now a sixth-year teacher—might have instead chosen another role in the education ecosystem.

“Teachers lead by example, and we need more passionate teachers that want to enter the profession to set this example for future generations,” says Castillon, who teaches history at Luis Valdez Leadership Academy. Her passion and accomplishments have inspired countless students who identify with her life experiences. The daughter of immigrant parents from Mexico, Castillon grew up in a low-income community outside of Los Angeles and received Perkins and Stafford federal loans to finance her undergraduate studies at Brown University.

As college graduation approached, Castillon knew she wanted to be involved in education, but she was unsure the path to become a teacher was the right one for her. Her parents were struggling financially, and, like many young people, Castillon felt competing tugs—to continue her education at the graduate level or to enter the workforce so she could help to support her family.

Fortunately, Castillon learned about multiple funding sources for her graduate teacher preparation studies. She received loans and service scholarships that covered 100 percent of her graduate studies and helped “fight against her urge” to return home after graduating from Brown, including the Assumption Program of Loans for Education forgivable loan, the Woodrow Wilson-Rockefeller Brothers Fund Fellowship for Aspiring Teachers of Color, and an Avery Forgivable Loan for Stanford students.

“Without the financial assistance, I don’t think that I would have enrolled in a teacher preparation program and pursued a Master’s degree,” says Castillon.

After graduating from Stanford’s teacher preparation program six years ago, Castillon taught history and government at Downtown College Prep in San Jose. In 2014 she moved to the Luis Valdez Leadership Academy in East San Jose, where she is the Founding Academic Dean and Mexican-American history teacher. Both schools serve a student population that is more than 90% low-income and Latino—students that the loan forgiveness programs incentivized Irene to teach. Castillon is also pursuing an administrative credential at San Jose State University.

Castillon’s passion for teaching has encouraged her first-generation students to believe that higher education, even teaching in their own community one day, is within their reach. One of her students—a DREAMer on a full-ride scholarship at Loyola Marymount University—wrote her this note: “I thank you for … believing in me when I didn’t believe in myself and making me fall in love with history and teaching. Can I be like you when I grow up? I want to be someone’s Ms. Castillon one day!”

External Reviewers

This brief benefited from the insights and expertise of three external reviewers: Li Feng, Associate Professor of Economics at Texas State University-San Marcos; Rachel Lotan, Emeritus Professor at Stanford Graduate School of Education; and Barnett Berry, founder and CEO of the Center for Teaching Quality. We thank them for the care and attention they gave the brief. Any remaining shortcomings are our own.

How Effective Are Loan Forgiveness and Service Scholarships for Recruiting Teachers? by Anne Podolsky and Tara Kini is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Research in this area of work is funded in part by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Ford Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Sandler Foundation.