Summary

Widespread efforts to curb exclusionary and discriminatory discipline in schools have led to a growing focus on restorative approaches, a set of practices aimed at building strong in-school relationships and attachments, rather than pushing students out of school. This brief reviews research illustrating the benefits of these practices for improving student behavior, decreasing the use of exclusionary discipline, and improving school climate.

Introduction

Repeated police violence against unarmed Black civilians, made more visible by the attention focused on George Floyd’s murder in 2020, has led to nationwide calls to overhaul policing both in society and in schools, where mistreatment of Black students and other students of color has been consistently documented.Gregory, A., Skiba, R., & Noguera, P. (2010). The achievement gap and the discipline gap: Two sides of the same coin? Educational Researcher, 39(1), 59–68; Skiba, R., & Knesting, K. (2001). Zero tolerance, zero evidence: An analysis of school disciplinary practice. New Directions for Youth Development, 92, 17–43. As a result, many districts have recently taken action to remove police from their schools, including several large urban districts, such as Seattle and Minneapolis.Riser-Kositsky, M., & Sawchuck, S. (2021, June 4). Which districts have cut school policing programs? Education Week (accessed 09/08/21). In addition, there has been a growing recognition of the harms of exclusionary discipline policies, which address a wide range of student behaviors with suspensions and expulsions rather than more educative approaches that keep students in school.

As a result, many schools have sought to replace harsh disciplinary policies with restorative approaches, which “proactively build healthy relationships and a sense of community to prevent and address conflict and wrongdoing.”Schott Foundation for Public Education, Advancement Project, American Federation of Teachers, & National Education Association. (2014). Restorative practices: Fostering healthy relationships and promoting positive discipline in schools. Unlike zero-tolerance approaches, which seek to hold students accountable through punitive discipline—often in the form of classroom or school removals—restorative approaches achieve accountability through the development of caring, supportive relationships and through strategies that allow students to reflect on their behavior and make amends when needed to preserve the health of the community. The science of learning and development indicates that students will be most inclined to demonstrate positive behavior when their school climates and relationships inspire feelings of trust, safety, and belonging. Instead of compelling students to meet expectations by rewarding desired behaviors and punishing misbehavior, restorative approaches promote student investment and responsibility for shared routines and norms.Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Learning Policy Institute.

Initially framed in terms of restorative justice, this approach began as a strategy of responding to unwanted behavior with strategies for mediation, helping students reflect on the results of their behavior, and finding ways to make amends to rejoin the community, rather than being pushed out of school. The framework for restorative practices has expanded to include the means not only for solving conflicts and addressing inappropriate school behavior, but also for achieving shifts in school culture by strengthening in-school relationships and infusing practices such as social and emotional learning and community-building activities into the school day.

Restorative approaches to building school community and encouraging positive behavior require a significant shift away from how schools and districts have traditionally attended to discipline and school culture. For many, this requires unlearning practices and perspectives on accountability that have been predominant, not only in our schools but in society at large. In this brief, we present the evidence for restorative approaches and describe what they look like in schools. We also address the question of what it takes to shift the culture of schools and build the capacity of school practitioners to successfully implement restorative practices.

What Do Restorative Practices Look Like?

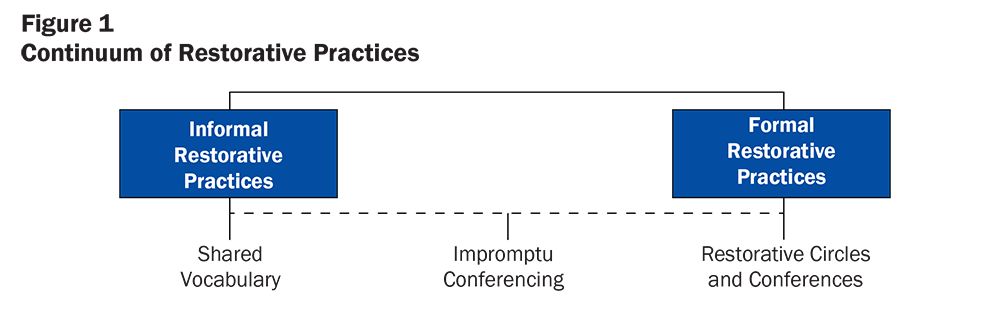

As shown in Figure 1, restorative practices range from the informal to the formal. They are designed to build community and repair relationships while supporting reflection, communication, and problem-solving skills for staff and students.

In a restorative school environment, staff and students typically have a shared vocabulary that enables community members to express feelings in a healthy, productive way. One of these practices is the use of affective statements, which focus on the perceptions and feelings of the speaker rather than the actions or attributes of the listener. For example, instead of saying, “You are being disrespectful,” a teacher might say, “I felt disrespected when you walked out of the classroom.”Wachtel, T. (2016). Defining restorative. International Institute for Restorative Practices. This shift in language reflects a key principle of restorative approaches, which is to criticize the deed, not the doer.

Another common practice is the impromptu student conference. An impromptu conference is used to redirect a student’s behavior in a way that minimizes disruption to instructional time. A teacher might use an impromptu conference if she notices a student distracted by side conversations. In such an instance, a teacher could invite the student to speak privately and then ask the student restorative questions, such as, “Is there anything going on with you today that I should know about?” or “How can I support you right now?” Often, a short, impromptu conference can refocus the student without necessitating a removal from the classroom or undermining the teacher–student relationship.

A cornerstone of restorative approaches is the use of restorative circles. These are structured processes that are guided by a trained facilitator, typically a teacher or other school staff member. A circle can be used for a wide range of purposes, such as building community, helping students connect their experiences to academic content, or welcoming a student back to school after an extended absence. As the name implies, restorative circles take place in a circle; there is a strong emphasis on the importance of listening, facilitated by using a talking piece. Participants know that they may speak when they are holding the talking piece but that otherwise, their job is to listen. An example of a restorative circle is shown below—in this case, reestablishing community for a student who has been away from the school for many months.

A Reentry Circle at Ralph Bunche High School

In the late afternoon, 15 people are gathered in a classroom for a restorative welcome and reentry circle at Ralph Bunche High School in Oakland, CA. A continuation school, Bunche is designed as an alternative for students who have been underserved in conventional high school settings. Many of the school’s 190 students come to Bunche with a history of disciplinary incidents and suspensions and some with prior involvement in the juvenile justice system.Oakland Unified School District. (2015). Ralph J. Bunche High School: Welcome to the school of resiliency. Bunche has utilized restorative approaches since 2012, and the work is guided by a full-time, on-site, restorative justice coordinator.

This reentry circle is for Cedric, a 16-year-old who has recently spent 10 months in a juvenile justice center because he brought a loaded weapon to school. The purpose of the circle is to help Cedric reenter school in a positive way, with support from his school community. The circle includes Cedric’s parents, the director of Cedric’s group home, the principal, school staff, a student peer, and several district administrators. The circle is facilitated by the school’s Restorative Justice Coordinator, Eric Butler.

Butler holds up a stone, the talking piece, and explains that participants will have the floor to speak when they are holding the talking piece. After some context setting and introductory relationship-building questions, Butler asks the circle participants how they plan to support Cedric in his transition back to school. He begins by saying, “I’m a person you can come to any time of day. I got your back.” When it’s the principal’s turn, she says, “I’m . . . going to ensure you get your high school diploma.” Cedric’s group home director says, “I’m gonna be the person who loves you—loves you to death.” It’s an overwhelming show of support, causing Cedric to smile broadly, cover his face with his hands, and say, “Y’all made me blush.”

Most successful circles have a turning point at which a shared sense of trust has formed and participants are willing to be more vulnerable. At this point in the circle, the group has coalesced around a shared sense of purpose; they are here to show Cedric that he has an opportunity for a fresh start and a network of support. Furthermore, Cedric has internalized that the group cares for him and wants him to succeed. Reflecting on this part of the circle, Cedric shared, “It touched me. It made me feel like I can do it. At first I didn’t really trust them, but then they . . . told the truth about how they felt . . . so I was like . . . I can give them a chance.”

In the concluding phase of the circle, the participants develop a support plan for Cedric. Butler will function as an on-campus go-to person for Cedric, and the group identifies school resources to support Cedric’s transition, such as tutoring and an internship program. They assign staff and family members to monitor the plan, and the group decides to reconvene a month later to monitor progress. Butler suggests that they end the circle by “showing Cedric and his mother some love.” It’s heartening to see how Cedric has transformed over the course of the circle, at first apprehensive and now all smiles, embracing the circle participants who have committed to supporting his transition back to school.

Source: Adapted from Oakland Unified School District. (n.d.). Restorative justice in Oakland schools [video recording]. https://www.ousd.org/Page/12328 (accessed 02/16/21).

Restorative conferences are similar to restorative circles but are used specifically to facilitate conflict resolution. Conferences are typically mediated by a skilled facilitator who has been trained on the restorative line of questioning. The facilitator will guide the participants through questions, such as the following: What happened? What were you thinking when this happened? Who was affected by what happened? What needs to happen to make this situation right?Wachtel, T. (2016). Defining restorative. International Institute for Restorative Practices. Restorative conferences include those involved in the conflict as well as those who were affected or harmed by the conflict, and the purpose of the conference is to move the participants from a place of disconnection to a place of connection, in which feelings have been acknowledged and a means for repairing harm has been agreed upon.

Restorative practices represent a tidal shift away from the zero-tolerance discipline and safety policy that dominated the education landscape for several decades. This approach emphasized compliance approaches to discipline, sought through a range of escalating punishments for behavior that include a heavy emphasis on exclusion from school through suspension and expulsion.

The Harmful Impact of Exclusionary Discipline

A substantial body of research shows that suspensions and expulsions are strongly linked to a wide range of negative outcomes for students, including missed instructional time, low achievement on standardized exams, involvement in the juvenile and criminal justice systems, and high school dropout.Gregory, A., & Ripski, M. (2008). Adolescent trust in teachers: Implications for behavior in the high school classroom. School Psychology Review, 37, 337–353; Skiba, R., & Knesting, K. (2001). Zero tolerance, zero evidence: An analysis of school disciplinary practice. New Directions for Youth Development, 92, 17–43. Students who have been suspended are three times more likely to drop out of high school by 10th grade than students who have never been suspended.Schott Foundation for Public Education. (2012). The urgency of now: The Schott 50 state report on public education and black males (accessed 10/21/21).

The negative outcomes associated with punitive school environments are especially harmful for students of color and students with disabilities. Research dating back to 1975 has consistently documented the disproportionate use of punitive discipline practices for these student groups.American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. (2008). Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools? An evidentiary review and recommendations. American Psychologist, 63(9), 852–862; Fabelo, T., Thompson, M.,

Plotkin, M., Carmichael, D., Marchbanks, M., III, & Booth, E. (2011). Breaking schools’ rules: A statewide study of how school discipline relates to students’ success and juvenile justice involvement. Justice Center: The Council of State Governments and the Public Policy Research Institute; Gregory, A., Skiba, R., & Noguera, P. (2010). The achievement gap and the discipline gap: Two sides of the same coin? Educational Researcher, 39(1), 59–68; Krezmien, M., Leone, P., & Achilles, G. (2006). Suspension, race, and disability: Analysis of statewide practices and reporting. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 14(4), 217–226. A 2014 report issued by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights indicates that Black students, in particular, are suspended and expelled at three times the rate of White students and that students with disabilities are twice as likely to receive a suspension than students without disabilities.Loveless, T. (2017). How well are American students learning? Brown Center on Education Policy at Brookings; U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. (2016). 2013–2014 Civil rights data collection: A first look. The same report indicates that Black students are more than two times more likely to be referred to law enforcement or arrested than White students.U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. (2016). 2013–2014 Civil rights data collection: A first look. Research has also confirmed that this overrepresentation is not because Black students display higher rates of misbehavior than other students but because they are punished more harshly for similar offenses.Fabelo, T., Thompson, M., Plotkin, M., Carmichael, D., Marchbanks, M., III, & Booth, E. (2011). Breaking schools’ rules: A statewide study of how school discipline relates to students’ success and juvenile justice involvement. Justice Center: The Council of State Governments and the Public Policy Research Institute; Gregory, A., Skiba, R., & Noguera, P. (2010). The achievement gap and the discipline gap: Two sides of the same coin? Educational Researcher, 39(1), 59–68; Skiba, R., & Knesting, K. (2001). Zero tolerance, zero evidence: An analysis of school disciplinary practice. New Directions for Youth Development, 92, 17–43; Skiba, R., Michael, R., Nardo, A., & Peterson, R. (2002). The color of discipline: Sources of racial and gender disproportionality in school punishment. The Urban Review, 34(4), 317–342. More recent research documents that additional student groups, including Latinx students and Native American students, are harmed by these policies as well.Losen, D., & Martinez, P. (2020). Lost opportunities: How disparate school discipline continues to drive differences in the opportunity to learn. Learning Policy Institute and the Center for Civil Rights Remedies at the UCLA Civil Rights Project; Skiba, R., Horner, R., Chung, C., Rausch, M.K., May, S., & Tobin, T. (2011). Race is not neutral: A national investigation of African American and Latino disproportionality in school discipline. School Psychology Review, 40(1), 85–107; Skiba, R., & Knesting, K. (2001). Zero tolerance, zero evidence: An analysis of school disciplinary practice. New Directions for Youth Development, 92, 17–43.

Zero-tolerance approaches were accompanied by a surge of hard security in schools, including the widespread use of security equipment—such as surveillance cameras and metal detectors—and the increased presence of school resource officers to monitor student behavior.Kupchik, A. (2010). Homeroom Security: School Discipline in an Age of Fear. New York University Press; Nolan, K. (2011). Police in the Hallways: Discipline in an Urban High School. University of Minnesota Press. As a result, incidents previously resolved internally by educators, such as class disruptions or physical altercations, are more often referred to school police and then to municipal police. This has contributed to the disproportionate criminalization of Black and Brown youth, a phenomenon that has expanded what is now called the school-to-prison pipeline.American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. (2008). Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools? An evidentiary review and recommendations. American Psychologist, 63(9), 852–862.

Though an assumed benefit of removing misbehaving students from school is a more orderly environment, schools with greater levels of student exclusion have poorer ratings of school climate. Research indicates that, rather than deterring future misbehavior, exclusionary discipline policies increase the likelihood of future misbehavior.American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force. (2008). Are zero tolerance policies effective in the schools? An evidentiary review and recommendations. American Psychologist, 63(9), 852–862. The well-documented, harmful consequences of zero-tolerance policies have contributed to a rapid expansion in the interest in and implementation of restorative approaches across schools in the United States.

Impact of Restorative Approaches on Student and School Outcomes

A growing body of research indicates that restorative practices are beneficial. In interpreting this research, it is important to understand that restorative practices are defined in myriad ways across studies. In many cases, studies are focused on narrower approaches to what are often called “restorative justice” programs, which affect relatively few students in a school because they address only interventions for offending behavior rather than holistic approaches to improving school climate and relationships. Other studies address the broader range of practices we described earlier that take a schoolwide approach. The evidence for narrow approaches is not as strong as the evidence for universal approaches. For this reason, we have taken great care to clarify what we mean by restorative approaches and to examine studies that seek to utilize a whole school approach.

As research findings accrue, they point toward positive impacts of restorative approaches on student behavior, disciplinary outcomes and disparities, and school climate. Numerous descriptive studies have found that restorative practices are not only associated with improvement in student behavior (e.g., decreases in fighting and bullying),Lewis, S. (2009). Improving school climate: Findings from schools implementing restorative practices. International Institute for Restorative Practices; McCold, P. (2002). Evaluation of a restorative milieu: CSF Buxmont school/day treatment programs 1999–2001. International Institute for Restorative Practices E-Forum; McMorris, B. J., Beckman, K. J., Shea, G., Baumgartner, J., & Eggert, R. C. (2013). Applying restorative practices to Minneapolis Public Schools students recommended for possible expulsion: A pilot program evaluation of the Family and Youth Restorative Conference Program. School of Nursing and the Healthy Youth Development–Prevention Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota. but also with a decrease in office referrals, classroom removals, suspensions, and expulsions.Armour, M. (2013). Ed White Middle School restorative discipline evaluation: Implementation and impact 2012/2013. Institute for Restorative Justice and Restorative Dialogue; Baker, M. (2009). DPS Restorative Justice Project: Year three. Denver Public Schools; Davis, F. (2014). Discipline with dignity: Oakland classrooms try healing instead of punishment. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 23(1), 38–41; Fronius, T., Darling-Hammond, S., Persson, H., Guckenburg, S., Hurley, N., & Petrosino, A. (2019). Restorative justice in U.S. schools: An updated review. WestEd Justice & Prevention Research Center; González, T. (2015). “Socializing Schools: Addressing Racial Disparities in Discipline Through Restorative Justice” in Losen, D. (Ed.). Closing the School Discipline Gap: Equitable Remedies for Excessive Exclusion (pp. 151–165). Teachers College Press; Hashim, A., Strunk, K., & Dhaliwal, T. (2018). Justice for all? Suspension bans and restorative justice programs in the Los Angeles Unified School District. Peabody Journal of Education, 93(2), 174–189; Jain, S., Bassey, H., Brown, M., & Kalra, P. (2014). Restorative justice in Oakland schools: Implementation and impacts (prepared for the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights). Oakland Unified School District; Sumner, D., Silverman, C., & Frampton, M. (2010). School-based restorative justice as an alternative to zero-tolerance policies: Lessons from West Oakland. University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. These findings are corroborated by a randomized control trial (RCT) of a whole school restorative initiative, which examines outcomes from the 2015–16 and 2016–17 school years across 44 elementary, middle, and high schools in Pittsburgh, PA. The report finds that program implementation led to a reduction in disciplinary disparities between Black and White students and resulted in a 16% reduction in days lost to suspension, a finding that was statistically significant across several student groups, including Black students, students from low-income families, and students with disabilities.Augustine, C. H., Engberg, J., Grimm, G. E., Lee, E., Wang, E. L., Christianson, K., & Joseph, A. A. (2018). Can restorative practices improve school climate and curb suspensions? An evaluation of the impact of restorative practices in a mid-sized urban school district. RAND Corporation.

Studies also suggest a link between restorative approaches and improved school climate outcomes, including increased levels of student connectedness, improved relationships between students and teachers, and improved perceptions of school climate.Acosta, J., Chinman, M., Ebener, P., Malone, P. S., Phillips, A., & Wilks, A. (2019). Evaluation of a whole-school change intervention: Findings from a two-year cluster-randomized trial of the Restorative Practices Intervention. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 876–890; Brown, M. (2017). Being heard: How a listening culture supports the implementation of schoolwide restorative practices. Restorative Justice: An International Journal, 5(1), 53–69; Fronius, T., Darling-Hammond, S., Persson, H., Guckenburg, S., Hurley, N., & Petrosino, A. (2019). Restorative justice in U.S. schools: An updated review. WestEd Justice & Prevention Research Center; González, T. (2012). Keeping kids in school: Restorative justice, punitive discipline, and the school to prison pipeline. Journal of Law & Education, 41(2), 281–335; Gregory, A., Clawson, K., Davis, A., & Gerewitz, J. (2016). The promise of restorative practices to transform teacher-student relationships and achieve equity in school discipline. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 26(4), 325–353; McMorris, B. J., Beckman, K. J., Shea, G., Baumgartner, J., & Eggert, R. C. (2013). Applying restorative practices to Minneapolis Public Schools students recommended for possible expulsion: A pilot program evaluation of the Family and Youth Restorative Conference Program. School of Nursing and the Healthy Youth Development–Prevention Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota; Mirsky, L., & Wachtel, T. (2007). The Worst School I’ve Ever Been To: Empirical evaluations of a restorative school and treatment milieu. Reclaiming Children and Youth: The Journal of Strength-Based Interventions, 16(2), 13–16. For example, an evaluation of a restorative program piloted in Minneapolis Public Schools found that students were more likely to report that they liked school and had an adult at their schools that they could talk to if they needed help after participating in a restorative conference.McMorris, B. J., Beckman, K. J., Shea, G., Baumgartner, J., & Eggert, R. C. (2013). Applying restorative practices to Minneapolis Public Schools students recommended for possible expulsion: A pilot program evaluation of the Family and Youth Restorative Conference Program. School of Nursing and the Healthy Youth Development–Prevention Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota. A separate study found that teachers who were perceived by their students as frequent implementors of restorative practices (as compared with teachers perceived as infrequent implementors) had better relationships with their students, based on survey items that asked students the extent to which their teachers liked them, enjoyed having them in class, and listened to them.Gregory, A., Clawson, K., Davis, A., & Gerewitz, J. (2016). The promise of restorative practices to transform teacher-student relationships and achieve equity in school discipline. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 26(4), 325–353. Findings from an RCT of restorative approaches in Pittsburgh Public Schools also documented statistically significant increases in teacher-reported school safety in schools that had implemented restorative practices.Augustine, C. H., Engberg, J., Grimm, G. E., Lee, E., Wang, E. L., Christianson, K., & Joseph, A. A. (2018). Can restorative practices improve school climate and curb suspensions? An evaluation of the impact of restorative practices in a mid-sized urban school district. RAND Corporation.

Research has also pointed out—both directly and indirectly—the challenges in implementing restorative practices. For example, a recent RCT evaluating the impact of restorative programs across the state of Maine found little difference in the distribution of restorative practices between the treatment and the control groups of schools. As a result, the study detected no significant differences in impact between treatment and control groups, on average. However, stronger implementation of the restorative practices made a difference. Researchers found that students’ self-reported experience with restorative practices significantly predicted improved peer attachment, school climate, and social skills.Acosta, J., Chinman, M., Ebener, P., Malone, P. S., Phillips, A., & Wilks, A. (2019). Evaluation of a whole-school change intervention: Findings from a two-year cluster-randomized trial of the Restorative Practices Intervention. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 876–890.

A more recent study of a large-scale data set in California that allowed for statistical controls for student and school characteristics found that students with higher levels of exposure to restorative practices experienced less punitive discipline, as well as smaller racial disparities in discipline and improvements in academic achievement. These findings pertained to all groups of students.Darling-Hammond, S., Trout, L., Fronius, T., Cerna, R. (2021). Can restorative practices bridge racial disparities in schools? WestEd.

What Does It Take to Implement Restorative Approaches?

Because restorative approaches require a substantial shift away from traditional discipline and school climate practices, the work of integrating restorative approaches into school settings is complex and takes time. Studies of the implementation and effectiveness of restorative practices have elevated key lessons about what is needed to successfully implement restorative approaches, which we highlight here.

Incorporate restorative practices as one of many strategies for improving school culture

Restorative practices are most successful when they are incorporated into educational settings that use a range of strategies to promote positive school climates and relationships. For example, Bronxdale High School, located in the northeast section of the Bronx in New York City, has implemented a constellation of structures and restorative practices to transform itself into a caring school community that outperforms its peers in credit accrual, graduation rates, and postsecondary enrollment.

A recent study of Bronxdale shows that the school has allocated considerable resources toward a robust restorative approach, including two full-time positions for restorative deans with extensive experience using restorative practices. The deans provide professional development for staff on topics such as collaborative problem-solving and facilitating restorative circles. As a result, circles are used widely and for various purposes. For example, the school has facilitated 9th-grade orientation using restorative circles, and circles are used to build community in subject-area classes and advisories.

The success of Bronxdale’s restorative approach is rooted in the school’s commitment to building healthy in-school relationships and a positive school culture. The school prioritizes small class sizes, providing an opportunity for students and teachers to develop close relationships. Additionally, every student is assigned to an advisory that meets multiple times a week, ensuring that each student has a close connection with at least one adult. Bronxdale has also implemented a peer mentorship program in which pairs of 12th-grade students lead advisories for incoming freshmen. The program not only serves to introduce new students to the school culture but also serves as a means for 12th-graders to become school leaders who model expectations of student behavior. These practices and programs create regular opportunities for school members to build community and strong interpersonal relationships, creating a foundation for the success of restorative practices.

Utilize a whole school approach

In a whole school approach, restorative practices are used primarily as a tool to build community and relationships rather than as a reactive approach to disciplinary incidents. Implementing a whole school approach involves engaging all staff, not just teachers and administrators, in training and implementation. A hallmark of whole school restorative approaches is a tiered system in which lower tiers include proactive practices that build a positive school community for all students and upper tiers specify nonpunitive responses to disciplinary incidents. The Oakland Unified School District, for example, has implemented a three-tiered model for restorative approaches. Tier 1 practices are intended for all students and include social and emotional skill development and informal restorative practices for community and relationship building. Tiers 2 and 3 include practices such as nonpunitive responses to harm and/or conflict as well as support for students’ successful reentry following suspensions, extended absence, or incarceration (see the discussion in “A Reentry Circle at Ralph Bunche High School” above).Oakland Unified School District. (n.d.). Restorative justice (accessed 02/16/21).

Focus on building staff buy-in and capacity

Because restorative methods represent a departure from the way that schools have traditionally approached discipline and school culture, building practitioners’ capacity to operate within a restorative framework is essential. Support of leadership is critical for two reasons: First, school leaders must understand and be able to model restorative practices and provide feedback to their staff. Second, when school leaders are invested in restorative approaches, they are able to serve as necessary champions for school-level change. Although support from school leadership is crucial, buy-in must be present at all levels to sustain restorative approaches, as administrator turnover is inevitable.

Consider, for example, the substantial investments in resources that were required to implement the Pursuing Equitable and Restorative Communities (PERC) program in Pittsburgh Public Schools (PPS):Augustine, C. H., Engberg, J., Grimm, G. E., Lee, E., Wang, E. L., Christianson, K., & Joseph, A. A. (2018). Can restorative practices improve school climate and curb suspensions? An evaluation of the impact of restorative practices in a mid-sized urban school district. RAND Corporation.

- 4 full days of professional development to introduce all school staff to the core principles of restorative approaches and train staff on how to facilitate restorative practices, provided by the International Institute for Restorative Practices (IIRP)

- the creation of school-based restorative teams that met regularly with an IIRP coach

- on-site IIRP coaching visits in which coaches modeled restorative practices, observed classrooms, and provided feedback to school staff

- monthly professional learning groups in which staff discussed their experiences with restorative practices

The investment made by PPS illustrates the intensive resources needed to build knowledge and skills among staff so they can successfully implement restorative approaches.

Because of the sustained and intensive supports required for implementation, investment in restorative approaches is a long-term endeavor, not a quick fix. For example, a study of the implementation of restorative approaches in Baltimore Public Schools suggests 3–5 years as a reasonable timeline.Fronius, T., Darling-Hammond, S., Persson, H., Guckenburg, S., Hurley, N., & Petrosino, A. (2019). Restorative justice in U.S. schools: An updated review. WestEd Justice & Prevention Research Center; Open Society Institute-Baltimore. (2020). Restorative practices in Baltimore city schools: Research updates and implementation guide. It is important that district and school staff understand from the outset that it takes time to develop the buy-in and capacity needed to successfully implement restorative approaches and that results on student outcomes should not be expected prematurely.

Develop meaningful accountability and data collection systems

Districts and schools should think strategically about the types of accountability systems that will allow them to implement and evaluate restorative approaches to discipline. This includes the development of data collection systems that accurately document behavior incidents as well as school responses (e.g., restorative circle, detention). Additionally, school discipline data should be publicly available in formats that easily allow for disaggregation by race, gender, and other student subgroups. This will support schools in determining whether restorative practices are leading to desired changes and guide schools in making course corrections as needed.Augustine, C. H., Engberg, J., Grimm, G. E., Lee, E., Wang, E. L., Christianson, K., & Joseph, A. A. (2018). Can restorative practices improve school climate and curb suspensions? An evaluation of the impact of restorative practices in a mid-sized urban school district. RAND Corporation.

Additionally, districts and schools need access to multiple measures of school safety and school climate, beyond records of behavior incidents and disciplinary responses. Given that restorative approaches emphasize improving in-school relationships and overall school climate, survey measures that capture student, teacher, and parent perceptions of school safety and climate are essential for measuring the impact of restorative approaches. Several validated surveys, available to schools and districts at no cost, measure school climate and students’ social and emotional well-being. States can support districts in using these measures in their accountability systems. For example, California’s latest budget allocates $6 million to train districts on using school climate surveys.Edgerton, A. (2021, July 27). Leveraging recovery funds to prioritize wellness and accelerate learning [Blog post] (accessed 07/30/21).

Establish district-level infrastructure

District-level policy that supports restorative approaches goes a long way. Not only does it send a strong message in support of restorative approaches, but it also increases the likelihood that districts will provide needed support for implementation. Districts have enacted supportive policies in varied ways. Several districts, including large urban districts, such as Pittsburgh, Denver, New York City, and Oakland, have revised their codes of conduct to include restorative interventions as responses to instances of misbehavior. In some cases, revisions to the discipline code have been accompanied by additional state or district policies. For example, California has eliminated the use of suspensions as a disciplinary response to “disruption and willful defiance” for k–8 students; “disruption and willful defiance” is an ambiguous category that includes offenses such as refusing to take off a hat or not turning in homework.Frey, S. (2015, May 14). Oakland ends suspensions for willful defiance, funds restorative justice. EdSource.

In Baltimore, the district CEO and the Board of School Commissioners pledged to make Baltimore City Schools (City Schools) a restorative practice district. In 2017, City Schools released its Blueprint for Success, which adopts restorative practices across the district and outlines plans for intensive training for 15 schools. As part of the district’s transformation to a restorative district, many central office staff, including school social workers, the entire Baltimore City School Police force, and Family and Community Engagement Liaisons, have participated in training focused on restorative practices.Open Society Institute-Baltimore. (2018). Baltimore City Public Schools restorative practices report. These types of district-level commitments accelerate the use of restorative approaches in schools and provide support to in-school practitioners.

Center student and community voices

Across the country, youth and community-based organizations have led movements to eliminate punitive, zero-tolerance discipline—often accompanied by the presence of police—from schools and replace it with approaches focused on strengthening school communities and relationships. The Dignity in Schools Campaign, for example, is a national coalition focused on eliminating the school-to-prison pipeline. It has over 100 chapters and member organizations across the country. In 2020, the Dignity in Schools California chapter supported numerous local campaigns to eliminate police presence in schools, with victories in Oakland, Sacramento, and San Francisco, among several other districts. These campaigns were advanced by coalitions of student leaders and community-based organizations, such as the Black Organizing Project in Oakland, Californians for Justice, and Fresno Barrios Unidos.

In Fresno Unified School District, located in California’s Central Valley, youth have led the movement to strengthen school relationships and communities through restorative practices in partnership with Californians for Justice (CFJ), a statewide organization that engages youth in racial justice campaigns. Fresno students have succeeded in lowering the student-to-counselor ratio in their district, expanding race and social justice courses to all Fresno high schools, and moving the district to adopt and fund a restorative framework for district high schools. These efforts are part of CFJ’s Relationship Centered Schools campaign. The campaign was sparked by results of the California Healthy Kids Survey, which indicated that 1 in 3 high school students could not identify a single caring adult at school. Understanding the importance of relationships for enhancing student success and well-being, CFJ has partnered with Fresno (as well as three other school districts) to redesign schools with structures and practices that more systematically integrate social and emotional learning and develop systems to deepen relationships among students and staff.

Given the critical role that student leaders and youth and community organizations have played in advancing restorative approaches across California and the country, it is imperative that districts continue to center their perspectives, experiences, and expertise. Districts have approached this in varied ways. Padres & Jóvenes Unidos, which has organized for racial justice in Denver Public Schools (DPS) for over 2 decades, has worked closely with DPS to rewrite its disciplinary code and to codevelop restorative, culturally responsive disciplinary approaches.Advancement Project. (2020). Decades long fight by national, local organizations lead to unanimous school board vote in Denver (accessed 06/10/21); González, T. (2015). “Socializing Schools: Addressing Racial Disparities in Discipline Through Restorative Justice” in Losen, D. (Ed.). Closing the School Discipline Gap: Equitable Remedies for Excessive Exclusion (pp. 151–165). Teachers College Press. Similarly, community-based organizations, such as Restorative Justice for Oakland Youth (RJOY) and Catholic Charities of the East Bay (CCEB), have played a critical role in the Oakland Unified School District since the district adopted restorative approaches. RJOY and CCEB worked with Oakland Unified to develop a district vision for restorative practices, create a district implementation guide, and build the capacity of district staff to implement restorative practices successfully. Oakland has also implemented a Peer Restorative Justice Program, which trains several hundred student leaders each year so that they can facilitate restorative circles at their schools.

Conclusion

Draquari McGhee, a student leader with CFJ Fresno, explains:

School should be a place where no student has to worry about feeling excluded—where we can talk to a caring adult in our time of need. The need . . . for better relationships is universal. It’s something we all need to succeed in life.Californians for Justice. (n.d.). Fresno (accessed 06/28/21).

Draquari's statement reflects the motivating ideas behind activism across the country that has sought to eliminate police and zero-tolerance discipline from schools and to rededicate associated resources to restorative practices. These movements are propelled by overwhelming evidence that harsh disciplinary policies in schools, coupled with the presence of police, contributes to the criminalization of Black and Brown youth. Unlike zero-tolerance approaches, restorative practices are grounded in the science of learning and development in that they prioritize supportive relationships with adults, which are essential for students’ healthy development and academic success.Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Learning Policy Institute; Learning Policy Institute, & Turnaround for Children. (2021). Design principles for schools: Putting the science of learning and development into action. As evidence of the benefits of restorative approaches continues to accumulate, districts and schools have the opportunity to prioritize what students, families, and community advocates have long sought: safe, inclusive schools that promote well-being and connectedness.

Building a Positive School Climate Through Restorative Practices (research brief) by Sarah Klevan is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Funding for this project has been provided by the California Endowment and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, and Sandler Foundation. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.

Updated November 1, 2021. Revisions are noted here.