Districts Need Systems, Not Silver Bullets, to Advance Equitable Opportunities and Outcomes

In an era of landmark education reforms and investments, a number of California school districts are achieving extraordinary results with students across racial and socioeconomic groups. The Learning Policy Institute (LPI) study Closing the Opportunity Gap: How Positive Outlier Districts in California Are Pursuing Equitable Access to Deeper Learning reveals secrets to success in seven of these exemplary districts.

Spoiler alert—LPI found no silver bullets, no single-shot training programs, and no maverick heroes. Instead, these districts used complex, systematic approaches that were closely tailored to their communities’ needs.

These approaches promoted opportunities for all young people to develop critical thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, and communication competencies—often referred to as “deeper learning” skills. In recognition of historic inequities that have limited access to needed supports and challenging and engaging curriculum, these districts made opportunities available to all students, not just the privileged few. Lessons from these individual districts can provide policymakers, education leaders, and community partners with insights into how to close persistent opportunity and achievement gaps between students of color and their White counterparts and between the growing number of students living in poverty and their more affluent peers.

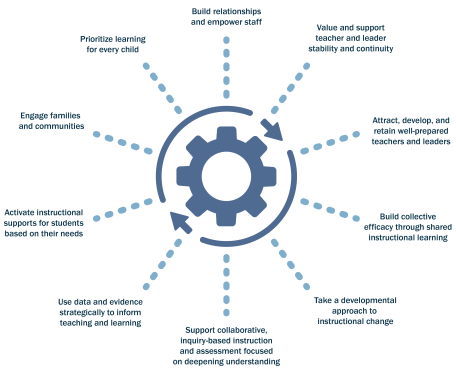

Among the high-leverage strategies found in common across the districts were the following:

Prioritize learning for every child. In positive outlier districts, leaders set a clear vision for teaching and learning, which they communicated throughout the district. Equity was a central part of this vision and served as a touchstone for student-centered decision-making. Although the district vision was universal—applying to all schools, staff, and students—leaders struck a balance between setting a clear vision from the district office and delegating considerable responsibility to school sites for how to enact that vision.

Build relationships and empower staff. District leaders supported instruction and intentionally built trusting relationships with teachers. They did this, for example, by prioritizing time for teachers to work together on instruction and by visiting classrooms and discussing instruction with teachers. Teamwork and collaboration were elevated as shared values and were central to the way districts approached continuous improvement. In Hawthorne School District, for example, district leaders worked with the Talking Teaching Networking, a non-profit organization, to help teachers unpack the standards and understand the necessary instructional shifts. Closely involving teachers harnessed their existing knowledge and helped build capacity and buy-in for the standards.

Value and support teacher and leader stability and continuity. Districts had relatively low rates of turnover in leadership, teachers, or staff. This stability contributed to the clarity of messages received from the district office and the long-term coherence of programs. It also allowed districts to build on their successes, fine-tune their efforts over time, and build strong capacity.

Attract, develop, and retain well-prepared teachers and leaders. Although many are high-poverty districts (which historically have the hardest time hiring and retaining fully prepared and experienced teachers), the positive outliers generally avoided the worst of California’s severe teacher shortages and hired relatively few underprepared teachers. These districts proactively created strong pipelines for educator hiring, often through partnerships with universities and “Grow-Your-Own” programs. For example, San Diego and Long Beach have long-standing relationships with local teacher education programs, and the districts received many student teachers and new teacher hires from these partners. They also worked hard to develop and retain teachers by providing mentoring for novices and ongoing opportunities for collaboration and professional growth.

Build collective efficacy through shared instructional learning. Positive outlier districts used collaborative professional learning as a key to school and district success. They built on existing structures, such as professional learning communities, to support teacher and administrator learning and problem-solving. Positive outliers also invested in teacher coaching, often accompanied by professional learning cycles. These inquiries typically centered on analyzing student learning, using data to inform instruction, and building teacher capacity to drive improvement. Sanger Unified School District, in particular, doubled down on the district’s long-standing investments in collaboration by providing ongoing training in effective professional learning communities. To augment their own capacity, districts also established strategic partnerships with external professional development organizations. These were sustained over time to introduce, develop, and refine specific skills.

Take a developmental approach to instructional change. Positive outlier districts took a phased approach to the implementation of the new standards, which increased teacher ownership and allowed for refinements in practices over time. They focused first on providing time for teachers to unpack the standards and understand what students should know and be able to do and then on engaging in professional learning to support instructional shifts. By building teacher capacity for instruction and engaging teachers in selecting and creating curriculum plans, materials, and assessments, districts helped teachers develop deeper understanding and ownership of the standards’ implementation. For example, in San Diego Unified School District, professional development began with principals and teacher leaders and was then shared with teachers through professional learning communities in their schools.

Support collaborative, inquiry-based instruction and assessment focused on deepening understanding. Positive outlier districts supported teachers as they made standards-aligned instructional shifts that provided students with greater opportunities to engage in inquiry and collaborative discussion in order to make meaning of their learning. As a teacher in Long Beach described, “I know when I first started teaching, the expectation was that kids are sitting quietly…. Now it’s the complete opposite. We want to hear productive talking.” Several districts also increased the use of newly designed formative assessments to gauge student progress and inform instruction. This approach favored mastery of standards over coverage of curriculum.

Use data and evidence strategically to inform teaching and learning. Positive outlier districts used data and evidence to improve practice, not to punish teachers or students. Educators used multiple sources of data and evidence—about student needs, behaviors, and outcomes across social, emotional, and academic domains, as well as about school and teacher practices. This analysis informed teaching and learning, identified students in need of supports, and was used to evaluate programs and interventions. Several districts made investments in data systems and professional learning on data analysis to boost teacher and school leader capacity to use data. An administrator from Clovis Unified School District said of the district’s long-standing commitment to data use, “We still collect data on almost everything, and we believe it’s what should drive our instruction.”

Activate instructional supports for students based on their needs. All positive outlier districts identified students for additional supports and targeted interventions, such as Reading Recovery and English language development instruction, to support their success. Additional supports for student learning, including for students with disabilities and English learners, were increasingly framed in terms of Multi-Tiered Systems of Support and encompassed both academic and social and emotional learning. Gridley Unified School District, for example, used several strategies to promote early literacy, such as Reading Recovery, and tiered interventions in elementary and middle school to address challenges.

Engage families and communities. Positive outlier districts engaged students’ families and leveraged community resources to support student success. Extending their services beyond the classroom walls and into the community was recognized as important for supporting student learning. Districts extended their services both by supporting caretakers and by seeking family and community input about district issues. For example, Chula Vista Elementary School District established liaisons to work with military families, and “promotores” that connect Spanish-speaking families to its Family Resource Centers.

The experiences and successes of these exceptional districts, representing diverse contexts— geographically dispersed; large and small; urban, suburban, and rural—offer valuable takeaways for policymakers, educators, and communities looking to empower educators and advance equitable opportunities and outcomes for each and every student.

Learn More

In-depth case studies provide an up-close look at each of the seven positive outlier districts studied.

- Chula Vista Elementary School District: Positive Outliers Case Study

- Clovis Unified School District: Positive Outliers Case Study

- Gridley Unified School District: Positive Outliers Case Study

- Hawthorne School District: Positive Outliers Case Study

- Long Beach Unified School District: Positive Outliers Case Study

- San Diego Unified School District: Positive Outliers Case Study

- Sanger Unified School District: Positive Outliers Case Study