How Can State Policymakers Foster Integrated Early Learning Environments?

This post was originally published on July 2, 2024 by the Education Commission of the States.

Integrated learning environments can lead to academic and social benefits for children, yet most early childhood education (ECE) programs are remarkably segregated as a function of both neighborhood segregation and policy decisions. New research shows how state policymakers can design policies in ways that foster integration rather than segregation.

Why Are Diverse Learning Environments Important?

Extensive research has shown the benefits of integrated K–12 settings, and emerging evidence indicates that the benefits of diversity may also be significant in ECE. Children learning in racially, linguistically, and economically integrated settings can show stronger language and learning gains. The earlier integrated education is introduced, the larger the gains. Exposing children to peers from diverse backgrounds also supports cross-cultural friendships and reduces biases early in their development. For children of color, segregation is often associated with concentrated poverty and resource inequities. Early childhood providers that are under-resourced struggle to provide quality learning environments, such as attracting and retaining staff. This is particularly important since stable, positive relationships are critical for a child’s development.

How Segregated Are ECE Settings?

A study of publicly funded preschools found that nearly half of Black and Latino/a children are taught in racially isolated schools where 90% of students are students of color. In fact, ECE programs are, on average, more racially segregated than elementary schools and high schools. Research shows that early childhood programs are segregated socioeconomically as well as by race and ethnicity.

Why Are ECE Settings So Segregated?

Although state and federal programs fund much-needed access to ECE, most are not designed to foster diversity. Only a few states offer universal access to preschool, and those that do are primarily focused on 4-year-olds. Public subsidies in ECE are often provided exclusively to families with low incomes, and regulations often drive programs to keep children from low-income families separate from their tuition-paying peers.

What Can State Policymakers Do?

- Establish universal ECE programs so that family income does not determine where a child can enroll. In 2022–23, the District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, New York, Oklahoma, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wisconsin had universal programs in which the majority of 4-year-olds participate. Several other states had universal eligibility that had yet to be fully implemented. Universal programs set the foundation for socioeconomic diversity by serving all children in one program, regardless of family income.

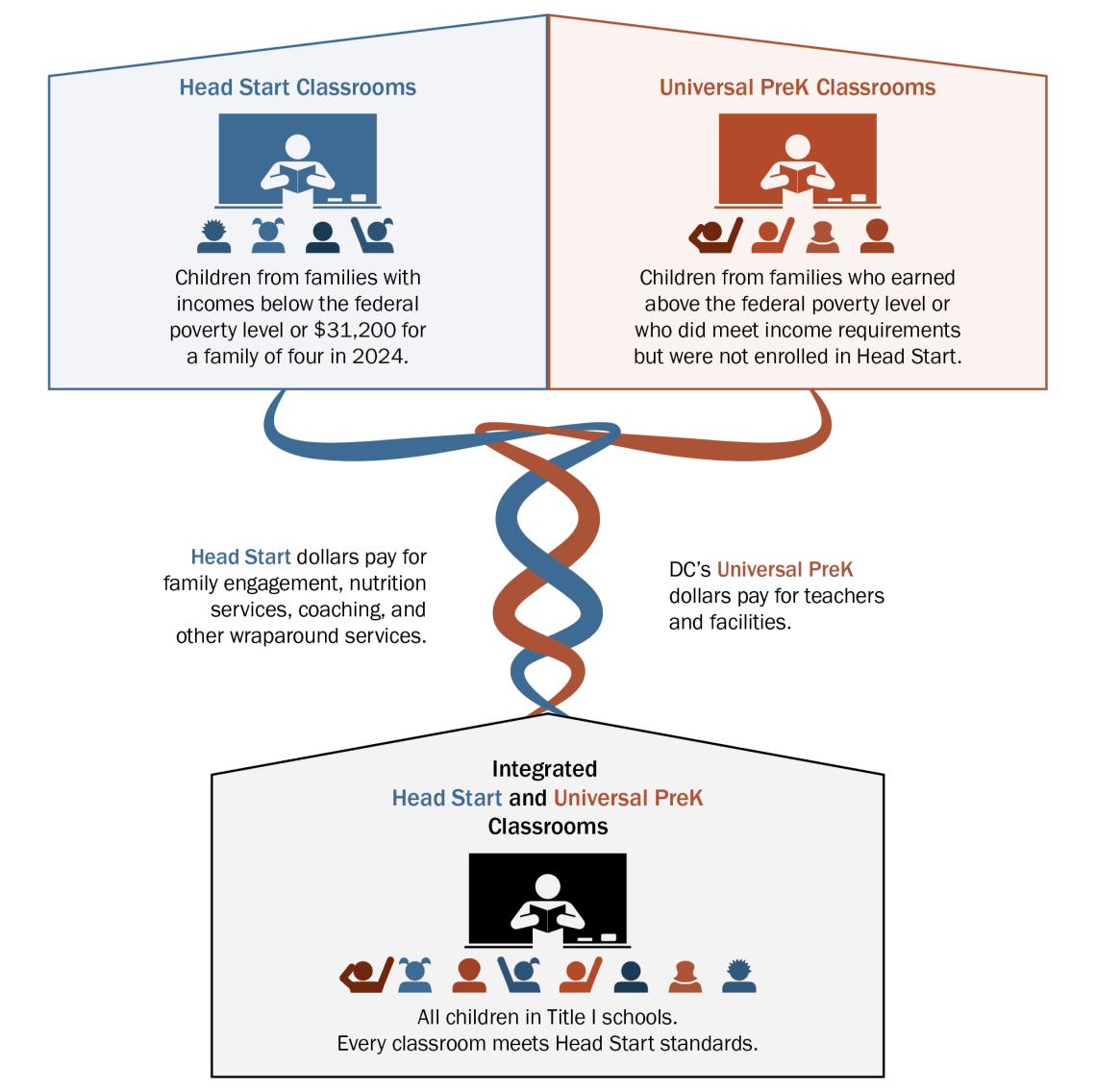

Figure 1: Washington, DC’s Head Start Schoolwide Model

- Take a leading role in braiding programs that have different eligibility requirements. Braiding at the state level removes this burden from individual providers. In Washington, DC, district-level administrators supported braiding by aligning universal PreK standards and Head Start standards. The city provided district schools with sufficient funding to meet Head Start standards, allowing children who are eligible for Head Start and those who aren’t to learn together (see Figure 1).

West Virginia makes preschool available to all 4-year-olds and requires collaboration across private providers, schools, and Head Start. In West Virginia, 82% of PreK classrooms are operated by districts in collaboration with community partners, including Head Start and child care providers. - Build a coherent system of governance and administration to support these integration strategies. For example, Alabama and Washington consolidated oversight of early learning programs within one agency, allowing them to align programs. Other states, like Michigan, house their early learning programs within the same department to improve coordination of early childhood services such as Head Start and state PreK.

Exposure to integrated environments can help ameliorate achievement gaps that take root before children enter kindergarten and build a more equitable, inclusive society. To learn more about how state policymakers can expand access to integrated settings, check out this webinar and report.