Restorative Justice at Fremont High School: Transforming Relationships and School Culture

This post is part of LPI's Educating the Whole Child blog series, which explores research, policy, and practices to support students' healthy growth and development.

Last November, Oakland students, family, staff, and community members gathered for Restorative Justice Day. As the gathering opened at Oakland’s Fremont High School, the after-school coordinator welcomed new arrivals, inviting them to have snacks and calling out the names of participating organizations: “We’ve got Restore Oakland in the house! We’ve got Californians for Justice in the house!”

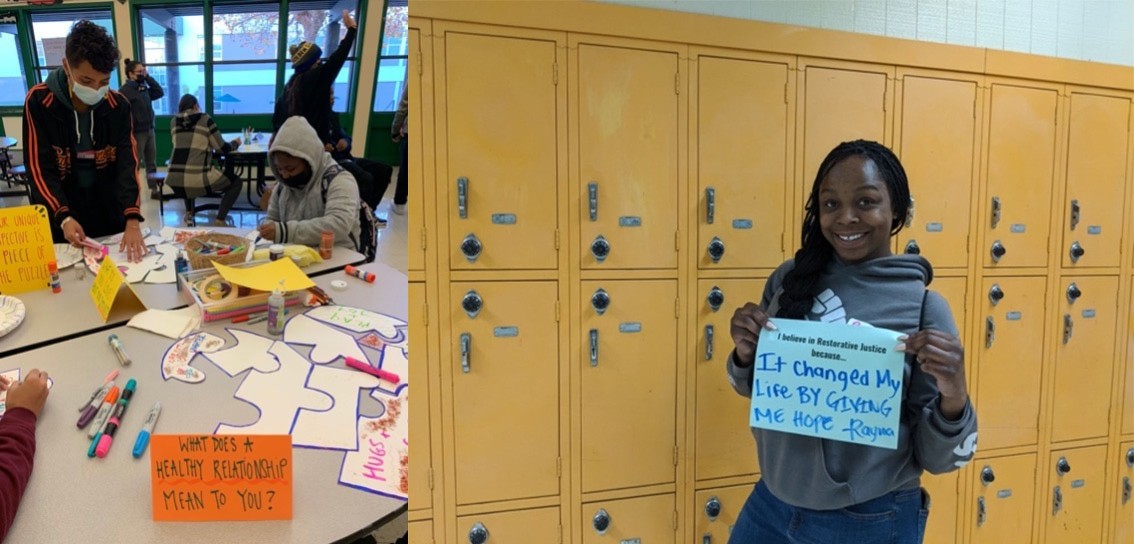

At the event, hosted by Fremont’s Restorative Justice program, Fremont students, staff, and members of local organizations participated in collaborative art projects. At one table, staff from Oakland Unified Restorative Justice arranged a project in which students created posters responding to the prompt, “I believe in restorative justice because….” Posters depicted sentiments such as, “I believe in RJ because everyone speaks and everyone listens from the heart,” and “I believe in RJ because relationships are where we learn, change, and grow.” At a nearby table, students draw and write on puzzle pieces in response to the question, “What does a healthy relationship mean to you?”

An event like this, which focused on such topics as violence prevention, healthy relationships, gender norms, and the criminal legal system, might seem outside the scope of restorative justice, often thought of as a practice focused solely on response to a conflict or crisis. However, as Fremont Restorative Justice Coordinator Tatiana Chaterji explained, “The biggest misunderstanding about RJ is that it is about the response [to an incident]. It absolutely can be. But at its core, RJ is about relationships, and being in positive relation to each other before there's a problem that needs to be addressed. It’s about building that foundation of trust.”

The Need for Restorative Approaches in Education

Increasingly, schools are adopting restorative practices and moving away from exclusionary discipline policies, such as suspensions and expulsions, which disproportionately impact students of color and students with disabilities. Racial disparities are most strongly linked with differential treatment of students, not differences in student behavior. Importantly, exclusionary discipline policies have negative consequences for student outcomes, including low achievement, lower rates of high school graduation, and involvement in the criminal justice system.

Restorative practices, in contrast, have proven to be beneficial for students, improving behavior, disciplinary outcomes, and school climate. These approaches shift the focus from punishment to developing communication strategies and building relationships and community, as well as explicitly teaching approaches to resolving conflict.

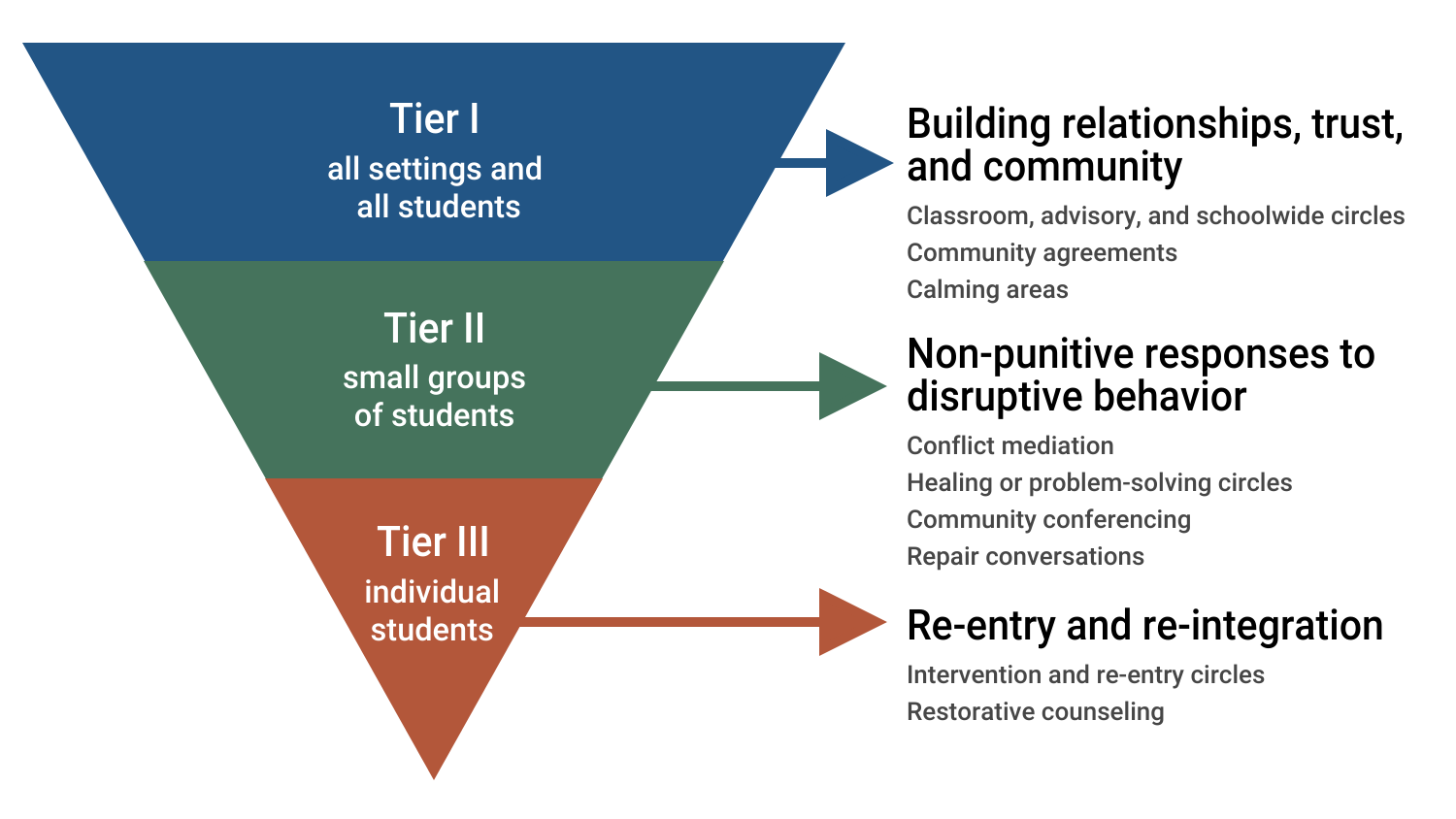

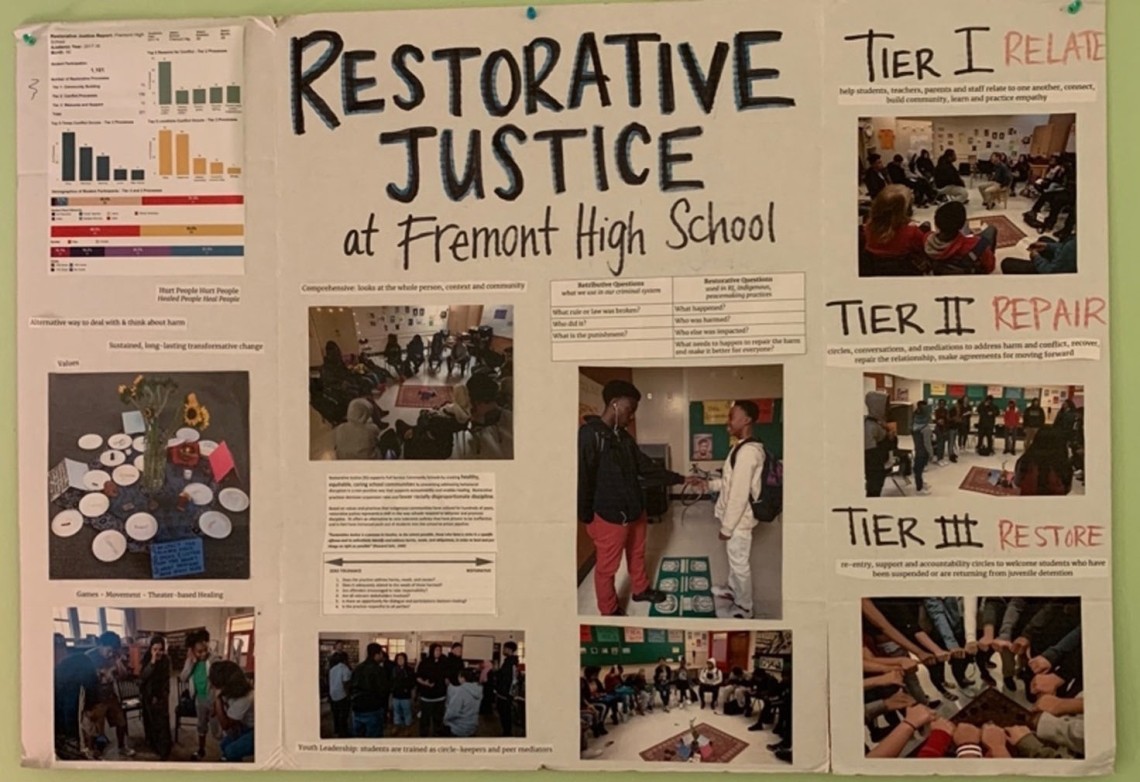

Many schools, Fremont among them, use a tiered system across the school, generally delineated by three tiers. Tier 1 includes proactive practices such as community circles that involve all students in strategies that build relationships and a positive school community. Tier 2 uses non-punitive responses to disruptive student behavior, such as a fight, involving smaller groups that include the harmed student, the person causing the harm, and a group of peers or adults who together resolve the conflict and enable students to make amends and correct the harm. Tier 3 strategies reintegrate youth who have had a sustained absence from school due to suspension, incarceration, illness, or another reason. Among Tier 3 practices are intervention circles, reentry circles, and restorative counseling. (See figure below for tiers and examples of strategies used.)

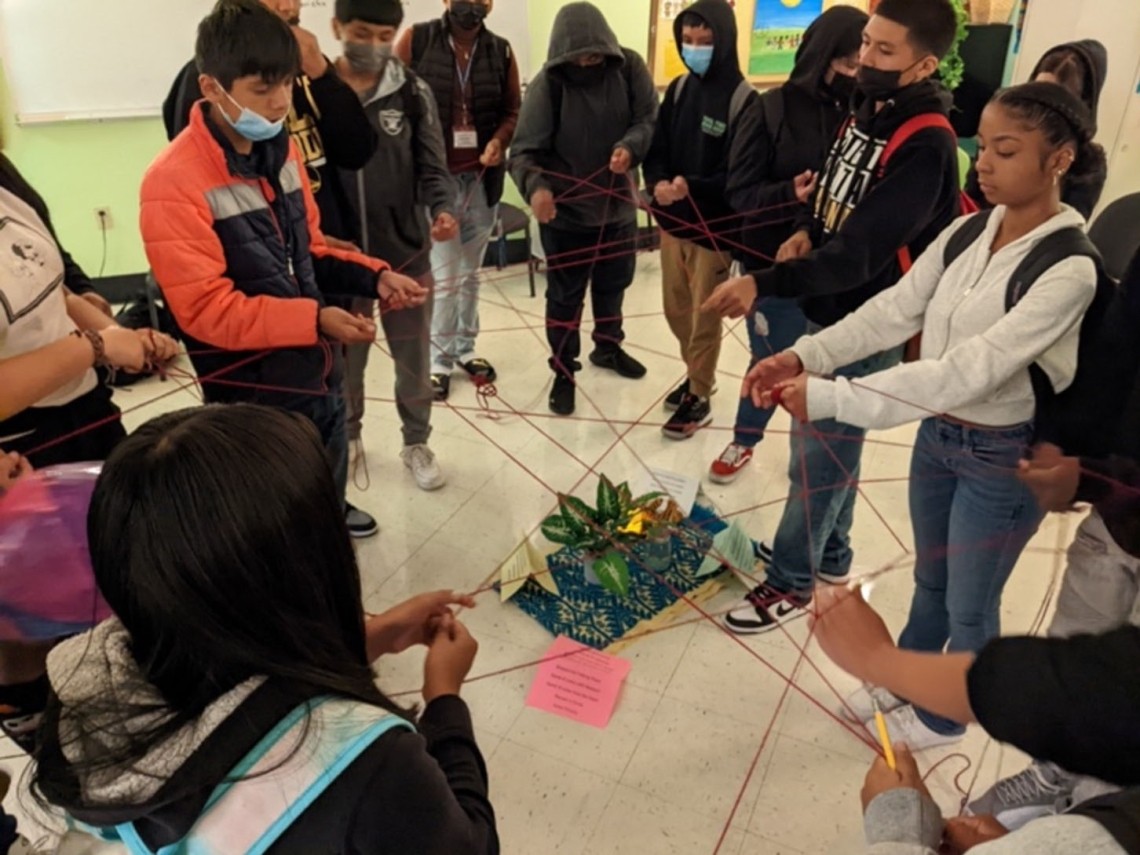

A cornerstone of restorative practice in all tiers is the use of circles—structured processes that are led by a trained facilitator, typically an educator, case manager, or student leader. Circles can be used for many purposes, including sharing experiences, surfacing feelings about various topics, building connections between academic content and students’ personal experiences, and supporting conflict resolution between students. The primary job of circle participants is to listen to others; only one person speaks at a time. “There are different types of circles for everything. You can make it something fun; you can make it something serious. And that’s the beauty of circles,” explains Kimberly Higareda, an RJ student leader at Fremont.

Siurave Quintanilla, another RJ student leader at Fremont, expressed how effective community circles can be for building understanding and connection among peers:

In one of our Spanish-speaking circles, a student was talking about their crossing [immigration journey to the United States] and what they miss about home. That felt very powerful because everybody was in tears. Everybody got to know this person, who’s super quiet, a little bit better. RJ can bring that out of people, even the quietest people. And they feel like they’re being heard and acknowledged.

Implementing Restorative Approaches

Restorative approaches require a substantial shift away from traditional school climate and discipline practices, often requiring that school staff unlearn practices and perspectives on accountability that have been predominant, not only in our schools but in society at large. As a result, the work of implementing restorative practices is complex, takes time, and requires committed leadership. For example, Chaterji describes the impact of Fremont High School Principal Nidya Baez, who has been a champion of restorative approaches:

There has been a push with this administrative team to have everybody to take [restorative justice] on. It should not just be [the RJ staff], it should be everybody making relationships happen, making community happen, and creating the conditions for learning by building safety and trust.

The following are key practices for successfully implementing restorative approaches in schools that are seen in action at Fremont.

1. Utilize a whole school approach.

Whole school restorative approaches serve, first, to create a culture of trust, inclusion, accountability, collaboration, and safety and, second, to repair harm and reintegrate individuals into the community when disruptive behavior occurs. Integrating all three tiers in school practice enables all students and staff to understand and actively participate—strengthening the effectiveness of restorative practices and fostering positive school climates.

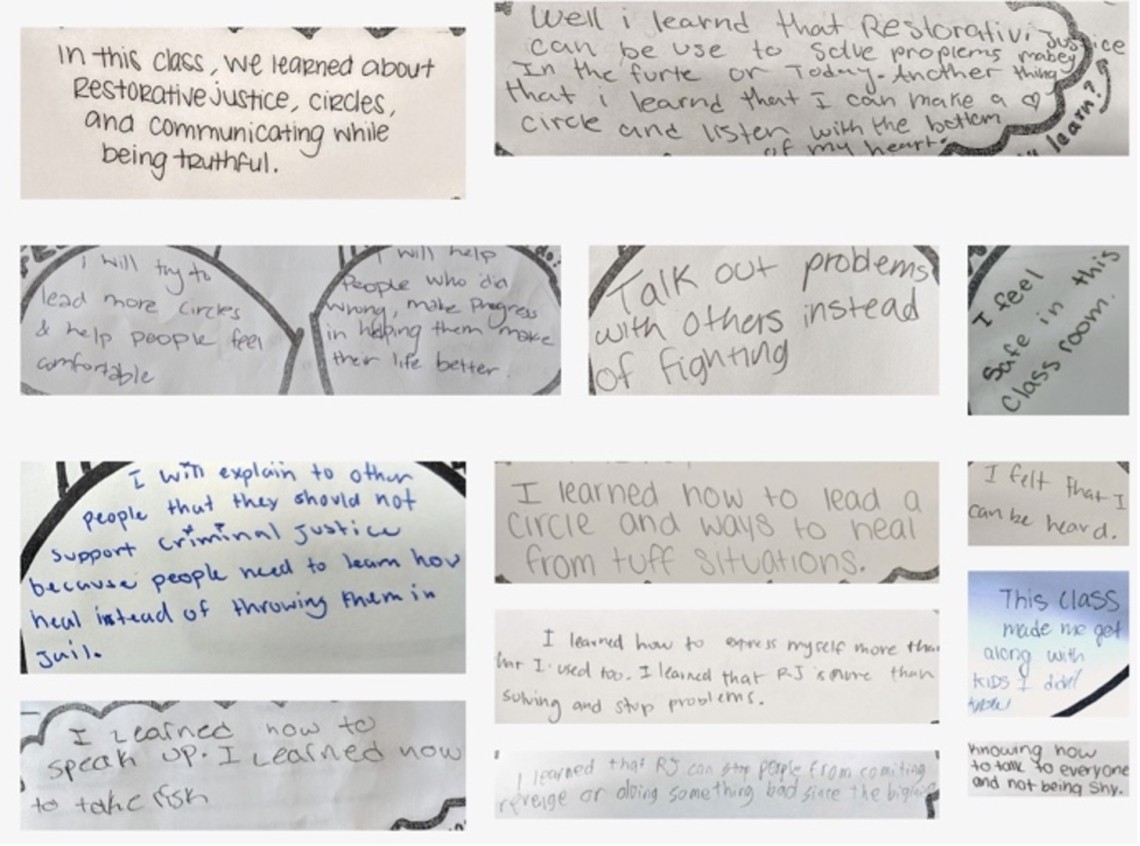

As part of its whole school approach, Fremont includes a 12-week class for most 9th-grade students to introduce them to the philosophy and key practices of restorative justice. The class also provides them with the opportunity to plan and lead community building circles.

Circles are an essential tool in every tier and, at Fremont, are used in advisory classes, in preparation for classes on sexual education, following traumatic incidents or losses, in after-school programs, and, by many teachers, in academic classes. Newcomer students, students who have been in the United States for less than 3 years and speak a language other than English at home, are introduced to restorative approaches through “language circles”—community building circles facilitated in their native language by student leaders. These circles, offered in Vietnamese, Mam (an indigenous Guatemalan language), Arabic, and Spanish, provide a meaningful opportunity for newcomer students to form relationships and feel more comfortable at school. “It has been hard for me to communicate with people who speak more English or Spanish,” says RJ student leader Jessica Pablo Chales, “but I have done circles in Mam, which is something that I cannot do in my classes. It’s a place where I can just speak my language and relate with other people who speak the same language as me."

2. Build staff and school leader capacity and investment in restorative approaches.

A whole school approach requires a focus on building the capacity of school staff. Chaterji supports educators through coaching and training opportunities so that staff can utilize restorative practices effectively. For example, during the first professional development session of the year, she trains the entire Fremont staff on circle facilitation. Her efforts are part of Oakland Unified’s work to provide restorative justice learning opportunities for school staff across the district.

Currently, several Fremont educators are participating in an inter-school professional learning community that supports staff engaged in restorative approaches offered by the district.

3. Incorporate restorative practices as one of many strategies for improving school culture.

Restorative practices are most successful when they are incorporated as one of many strategies, such as small class size, advisory systems, and mentorship programs, to promote positive school climates and relationships. At Fremont, these practices include a “week of welcome,” in which the first week of school focuses exclusively on building community in every class. Fremont has also incorporated advisories; affinity groups such as the Latin American Student Union and the Queer Students Association; several violence-prevention programs; a series of cultural events, including Yemeni Day and Polynesian Day; and a Black girls leadership and mentorship initiative.

4. Center student voices and leadership in restorative practices.

Inclusive school climates center student perspectives, experiences, and expertise in implementing and enacting restorative approaches. Fremont uses several strategies to develop student leadership in this context. For example, Fremont has partnered with Californians for Justice, which develops youth leadership by engaging young leaders in local organizing campaigns. Fremont also embeds student leadership within the school’s restorative practices through student-led circles.

Since introducing restorative approaches, Fremont has reduced its suspension rate by nearly 50 percent (from 15.2% in 2015–16 to 8.1% in 2021–22). The school’s enrollment rate has also increased, even as districtwide enrollment has fallen. Staff and students link these positive changes to restorative practices and community building strategies that the school has introduced in recent years. Stephanie Jauregui, a Fremont High School alumna and Oakland youth organizer at Californians for Justice, shared, “What I hear a lot from students is that they want to be taken seriously, and restorative justice gives them the feeling that their voice matters. For a lot of students, that’s what they need. That’s how they build trust with us, that’s how they build a relationship with us.… I see such a difference from when I was a student.”

Photo credit: Tatiana Chaterji, Fremont High School