William Smith High School: Prioritizing Community, Professional Development, and Authentic Learning

This post was originally published on March 28, 2024, by Assessment for Learning. It is part of the Transforming Schools series, which shares effective practices and foundational research for educators, students, families, and policymakers who are reimagining schools as places where students are safe and can thrive academically, socially, and emotionally.

He who devotes himself to learning (seeks) from day to day to increase (his knowledge); he who devotes himself to [wisdom] (seeks) from day to day to diminish (his doing).Lao tzu, Tao Te Ching

“This is not for everyone,” Kristin Wiedmaier Collins, principal of William Smith High School, told a room of educators during a recent site visit, “We realize that we can’t do everything, or be everything for everyone.” In a world where school leaders are sometimes asked to support nearly 30 separate priorities in a single site plan, refining that list to the essentials is a challenge—one that educators at William Smith take on with enthusiasm.

Walking through the school and seeing student’s Wes Anderson-inspired photos lining the walls, geodes on display outside of classrooms, and the meditation labyrinth out past the chicken coop, a visitor could be forgiven for thinking that this school is trying to do everything for everyone, though they’d be mistaken. Nearly 15 years ago, William Smith’s former principal received a mandate from the district—change things around, or else—that spurred them to clarify their vision and goals. They examined several models and identified project-based learning using the EL Education (formerly Expeditionary Learning) model as the way they wanted to do school.

Their first priority? Build community. In the first couple of years of the redesign, the school introduced structures to cultivate connections between staff and students. Students were invited to call staff by their first names, which is still the norm, as a way to invert power dynamics that can undermine authentic trust-building. Staff and students also launched Crew in those first few years, an essential element of the EL Education model that functions as a home base for students, similar to an advisory. Students spend all four years with the same Crew, building a tight-knit community with one another and their Crew leader who is a member of staff. In Crew, students set personal and academic goals, engage in self-reflection, participate in community service and team-building, and chart their academic journey alongside their peers. Each Crew has a name, with puns like “Into the Crewniverse” or inside jokes like “Dawn Dishsoap and Sarah Sponge” displayed on vibrant banners and artwork that line the walls.

August Adventures are another opportunity to build these relationships. Before school starts, educators and students venture into the mountains together to camp, hike, and experience outdoor activities. “Someone who thought they were tough before coming [to William Smith] now has to go hiking with everyone,” noted Kevin, a young man in his 11th grade year. “That totally changes [our dynamic] because you have to be vulnerable with each other.”

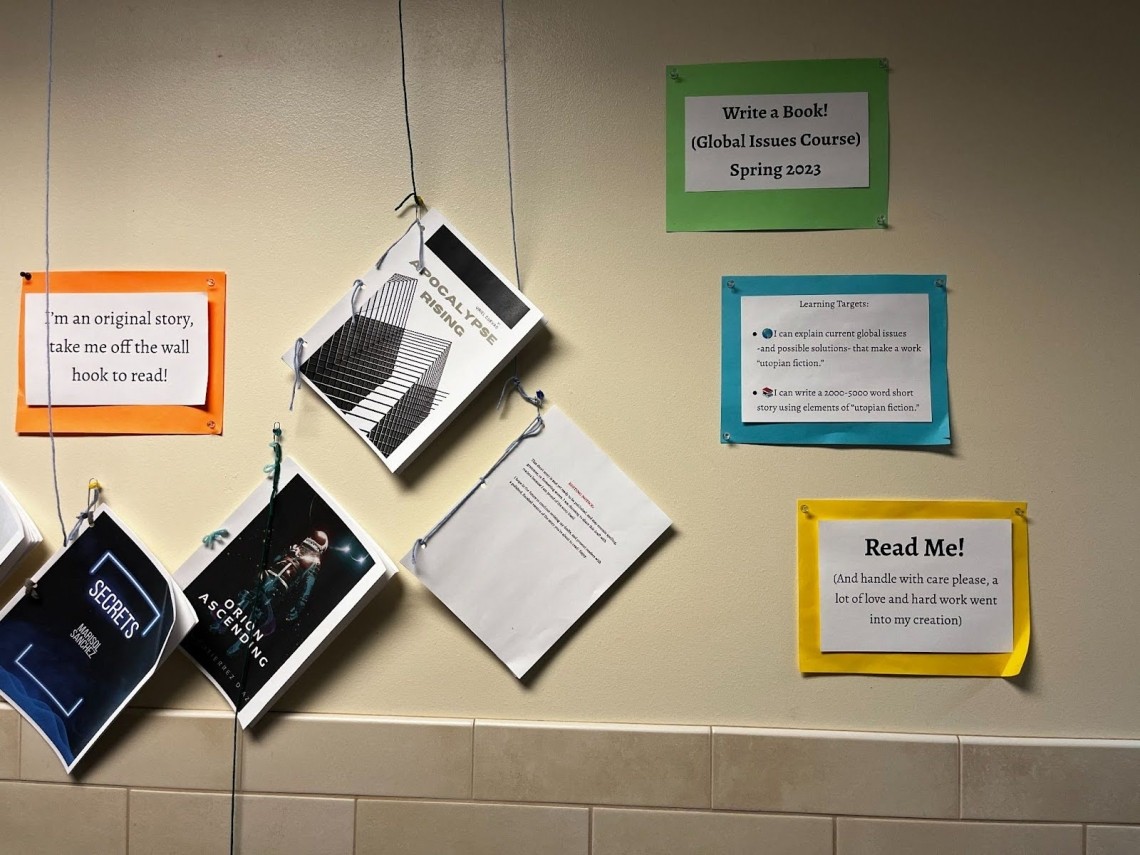

This dynamic extends to the school year, as well. “Our classes are weird, compared to other schools,” Kevin reflected with a chuckle. Educators work extensively to design classes where students can pursue their interests while gaining key skills in different content areas, like American Ninja Warrior (Math), Wes Anderson Cinematography (Art, English Language Arts), Write a Book (English Language Arts, Global Issues), or Battle Kites (Science, Math). Projects are authentic to students’ interests and reflect their personalities. Outside of one classroom, Utopian short stories of 2000-5000 words line the walls, asking passers-by to “take me off the wall hook to read!” Each one starts with the same first sentence then diverges onto a different path, as wide-ranging as the interests of the students who wrote them.

Kevin wants to pursue psychology, and he got a taste for this discipline in his class “How to Stress Like a Genius” where students explored the mind and how it works. Though he knows that his introductory courses in higher education might take a more lecture-based format, he still feels that, “after going to high school here, college feels less scary.” Research indicates that high-quality project-based learning can be a lever for equity, that students learn best when they can build on and connect to prior experiences, and positive developmental relationships provide a key catalyst for learning. In short, this type of learning is aligned to what research says about how to best support meaningful, lasting learning.

Best practices for student learning are not far from those that work for adults. Research indicates that integrating professional learning into the culture of the school can support its sustainability. Over the past 15 years since the school’s redesign, Principal Kristin Wiedmaier Collins has watched this integration happen. “When we first moved to project-based learning, we began with a, sort of, speed dating exercise,” she recalled, “where teachers had to choose a project idea that they might want to teach and share it with each of their colleagues to help them find a collaborator or thought partner.” Now, this type of unit planning is much more organic. “You see them meeting up in the hallways between classes to talk about an idea that they have for something new.”

Administrative support has been related to teacher retention before and beyond COVID-19 shut down schools. Providing teachers with engaging, energizing teaching opportunities can also help mitigate burnout and reduce teacher attrition. Several factors can contribute to burnout, including “test-based accountability policies, lack of influence over school policies and practices, lack of autonomy in the classroom, inadequate opportunities to collaborate with colleagues, and inadequate opportunities for leadership or professional advancement.” By providing focused, embedded professional learning that supports teachers in deepening their practice and content knowledge, William Smith both models for teachers the type of learning that it wants its students to experience and increases the likelihood that educators remain at the school to grow their expertise.

This system is not simple to orchestrate. While the school’s status as a pilot school allows it more autonomy with professional learning structures and flexibility in its schedule and hiring process, some school staff also chose to leave the school during their transition to project-based learning. “It just wasn’t for them, and that’s OK,” reflected Kristin Wiedmaier Collins, “It was no longer a fit, because we had changed our program.” The mismatch between the district’s Carnegie unit-based model and the school’s project-based one also requires an immense amount of backend engineering on behalf of Kristin and her Assistant Principal. “Because I taught here for so many years,” she observed, “I know what these courses look like, and I can sort out which credits to assign them in our system,” though she acknowledges that it is still time consuming to match up the current district credit system to a wide variety of project-based content.

This year, professional learning is focused on providing clear, shared expectations for student work using the school’s standards-based grading approach. This focus has Kevin’s seal of approval, who has raised his concerns about the subjectivity of grades both to individual teachers and to Kristin. “Because I have a relationship with the teachers,” Kevin shared, “I felt like I could push back when I experienced frustration with how some of my teachers graded my work.” This is the sort of student that William Smith hopes to develop: someone who can leverage his relationships, critical thinking, and analytical abilities to interrogate the world around him and work toward solutions. By distilling their core goals, educators have helped him to unearth and tend to these skills, which he is applying both now and–they expect–in the future.