For High-Quality Early Childhood Education, Invest in a Skilled and Supported Workforce

The research is clear: Early childhood education (ECE) matters.

The potential benefits of ECE for children, families, and society are significant, but they can only be realized if programs are high quality. While the jury is still out on the precise formula for realizing these benefits, an effective, stable, and diverse workforce provides the critical foundation for the other building blocks of quality. The nurturing relationships with caring adults that these programs can provide are invaluable in early childhood. And in ECE classrooms, teachers must also be able to provide the intentional, individualized instruction that capitalizes on children’s natural curiosity and embeds learning into everyday routines and play.

That’s no easy task, but skilled and experienced ECE teachers like Yvonne Smith at Central Park East 1 in New York City are adept at creating environments in which young children can grow and learn, academically and socially. Observing Smith in her classroom, it’s clear that she engages children as critical thinkers through guided play and exploration to build their knowledge and understanding of the world around them—from the eating habits of the class guinea pig to the decomposition of a pumpkin.

The Issue of Access

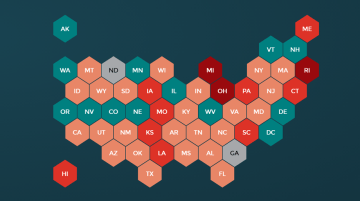

A discussion of the quality of early childhood education would be incomplete without acknowledging the issue of access. Across the country, publicly funded programs do not have the capacity to serve the children and families who qualify for them, even under often outdated and stringent income guidelines. In 2012, only one in six children eligible for federally funded child care assistance through the Child Care Development Block Grant received it. Similarly, in 2016, only 31% of eligible preschoolers had access to Head Start and just 6% of eligible infants and toddlers had access to Early Head Start.

The same holds true at the state level. For example, a recent report documented that only 33% of children under age 5 who qualified for one of California’s publicly funded ECE programs were served in 2015–2016, and many of these children were enrolled in part-day programs that don’t meet the needs of working parents. While the state is making strides toward meeting the needs of 4-year-olds—with roughly 69% of 4-year-olds from low-income families enrolled in some kind of ECE program—nearly 650,000 children birth to age 5 do not have access to the publicly funded ECE programs for which they are eligible.

Given the research demonstrating the importance of ECE in establishing school readiness, especially for children from low-income backgrounds, investments in the workforce, including those made at the federal level, need to be matched with the increased funding necessary to ensure equitable access to high-quality programs for all children. This combination of evidence-based practices and designated funding to increase access is reflected in an early education bill recently introduced by Senator Patty Murray of Washington State, ranking member of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, and Representative Bobby Scott from Virginia, ranking member of the House of Representatives Committee on Education and the Workforce.

For policymakers, the challenge of recruiting, retaining, and supporting teachers like Yvonne represents a substantial barrier to ensuring access to high-quality ECE across the country. While the current state of the workforce makes the challenge particularly daunting, recent research provides some guidance by outlining key elements of a high-quality system to achieve this goal, including improvements to teacher preparation and supports for ongoing professional development.

Many ECE programs—including the high-quality public preschool programs in Boston, Michigan, New Jersey, and Tulsa—require lead teachers to have a bachelor’s degree with a specialization in early childhood. Although these programs have made significant strides toward increasing teacher compensation in concert with qualifications, nationwide salaries for ECE teachers are far from competitive: The median salary for preschool teachers is approximately half that of kindergarten and elementary school teachers, with child care workers earning even less. In fact, between 2009 and 2013, 34% of pre-k teachers and 46% of child care workers relied on public assistance to meet the needs of their own families.

The current level of qualifications in the ECE workforce, paired with low wages, make a unilateral transition to this higher standard impractical for most states and districts. Instead, policymakers looking to build a more qualified workforce should offer a variety of clearly articulated pathways to earning a B.A. that include multiyear timelines, financial support, and commitments to compensating ECE teachers accordingly, as New Jersey, North Carolina, and Oklahoma have done. Together, these efforts would create both the opportunity and the incentive for existing early childhood educators to earn their degrees.

North Carolina has implemented just such a comprehensive strategy to increase the qualifications and competencies of all early childhood educators. The Teacher Education and Compensation Helps (T.E.A.C.H.) Early Childhood Scholarship Program, which started there, provides scholarships to help ECE providers pursue 2- or 4-year degrees in early childhood education. After completing a T.E.A.C.H.-sponsored program, each participant receives a predetermined raise or bonus paid for by his or her employer. North Carolina has also implemented the Child Care WAGE$ Project, which provides education-based salary supplements to ECE providers. In addition, the state requires all preschool teachers to hold a B.A. in order to be fully licensed, and it provides two pathways for doing so. Teachers can either earn a provisional license by completing their B.A. through a state-approved teacher-preparation program, or they can earn a lateral-entry license by completing their B.A. and then taking the teacher-preparation courses while working in a preschool classroom. Stakeholders in North Carolina report that these supports have been critical to successfully developing the ECE workforce. Before the program was implemented, no teachers were licensed and few held degrees.

Policymakers and practitioners should also work with institutions of higher education to ensure that preparation programs provide aspiring and existing teachers with the skills and content knowledge they need to thrive in the 21st-century ECE classroom. This includes core knowledge of child development, strategies for individualizing instruction, an understanding of how to serve diverse children and families, and familiarity with the child- and program-level tools and assessments integral to continuous quality improvement.

As states improve the quality of their ECE programs, it is also important that they preserve the field’s current racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity. On the whole, the early childhood workforce tends to more closely mirror the demographics of the country’s children than the k-12 workforce—and this diversity has benefits for these young learners. However, providers of color and recent immigrants are disproportionately represented in the lowest-paying segments of the field. Continuing to cultivate this workforce diversity will ensure that there will be opportunities for the lowest paid workers to advance.

To increase the effectiveness of the ECE workforce, policymakers must also create policies and provide funding to support a strong system of evidence-based professional learning. Research identifies several key characteristics of effective professional development (PD). First, it is content focused—meaning it is explicitly linked to the topics and lessons being taught by teachers in their own classrooms. Second, it incorporates active learning by giving teachers hands-on opportunities to practice new strategies and adjust them based on reflection and feedback. And third, effective PD provides opportunities for teachers to collaborate with peers or coaches, reflect and receive feedback on practice, and observe models of high-quality teaching. An example of policy that is aligned with these evidence-based practices can be found in the professional development requirements of the Head Start Program Performance Standards.

Coaching is an important aspect of teachers’ professional development. Through one-on-one sharing of expertise about content and evidence-based practices, coaches can focus on each teacher’s individual needs. Washington state’s Early Achievers coaching program is one example of how coaching can inspire and support early educators. While the evaluation of the program is still underway, stakeholders in Washington are already seeing its impacts. According to Ryan Pricco of Child Care Aware, “… using a coaching approach—in which programs have a coach on-site with them, working hand-in-hand with them to make daily improvements to their interactions with kids or simple improvements to their environment—very quickly and very efficiently improved the quality of care.”

The research documenting the benefits of coaching as part of a larger PD system led the National Institute for Early Education Research to revise the quality benchmark for PD in its State of Preschool 2016 yearbook to include coaching for lead and assistant teachers. Unfortunately, only four states met this quality benchmark for their pre-k programs—demonstrating the need for additional investments in ECE to support this method of delivering effective professional development.

Looking Ahead

There is work to be done to prepare and support the educators charged with the critical task of caring for young children and preparing them for school—and federal, state, and local policymakers all have an important role to play in this process. Raising pay for this important work, promoting high standards of qualifications and competencies, and supporting access to evidence-based professional learning are critical to ensuring every child gets the early learning experience they deserve from a caring, knowledgeable, and well-prepared teacher.

Image courtesy of Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action.