Keeping Schools Safe? The Research on Behavioral Threat Assessments

Summary

The ongoing occurrence of school shootings and a documented rise in reported threats have led most states to adopt policies requiring the use of behavioral threat assessments (BTAs). Despite there being several specified BTA models that focus on proactively responding to threats with appropriate interventions and student supports, many districts and schools adopt BTA practices that do not follow these specific models. Implementation challenges have raised concerns over potential unintended consequences of BTAs, including the use of punitive approaches with disparate impacts on students of color and students with disabilities. This brief summarizes the current evidence on the implementation and impacts of BTAs in schools. Overall, the research—heavily based on one BTA model—suggests that focusing on problem- solving approaches to threat response and intervention can support students and reduce exclusionary discipline practices, including disparities. The brief offers evidence-based considerations for education leaders looking to implement effective and supportive threat assessment strategies.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

Introduction

The ongoing occurrence of school shootings and a documented rise in reported threats have led educators and policymakers to seek ways to prevent and respond to acts and threats of school-based violence. These tragic events are often followed by calls to physically harden schools by installing metal detectors and security guards. However, the evidence does not suggest that these strategies are generally effective in preventing violence. A substantial body of research suggests that schools need to attend to the psychological safety of students as the foundation for ensuring their physical safety. This is especially true given that more than 85% of school shootings have been perpetrated by current or former students who experienced negative home and school lives, and around 80% of school shooting perpetrators had experienced bullying within the school.

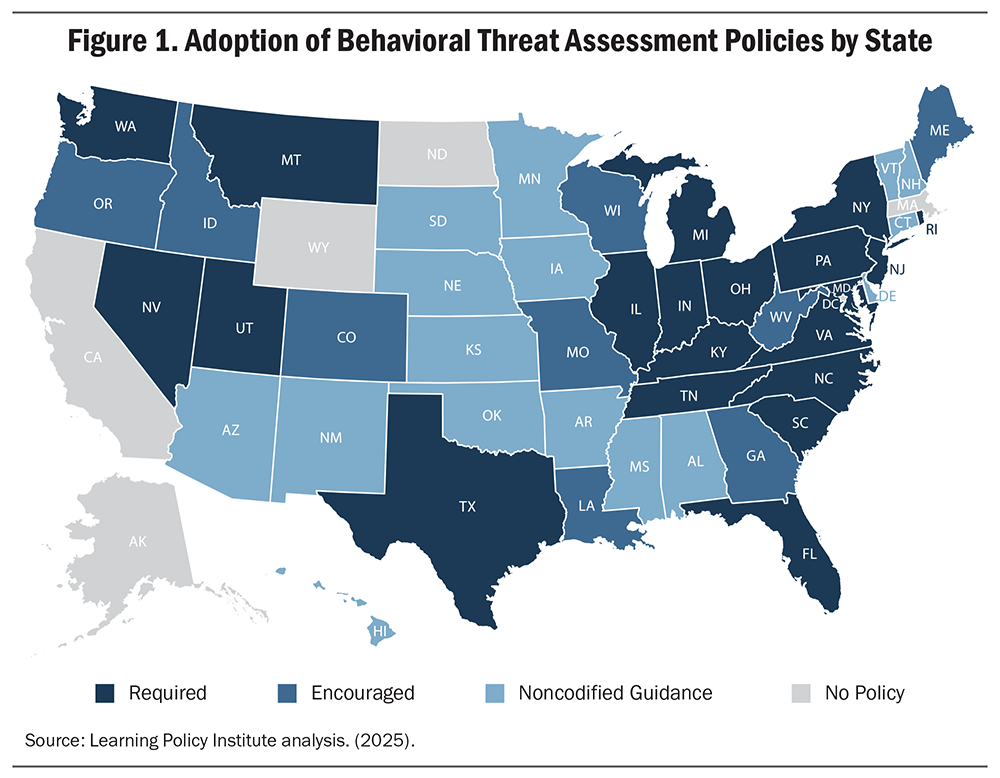

One approach that attempts to address both physical and psychological safety is the use of a behavioral threat assessment (BTA) system. These systems aim to identify, assess, and manage the threat of violence targeted at schools with the ultimate goal of intervening to prevent such violence. As of April 2024, 85% of schools across the United States reported having a threat assessment team, and, as of this publication, 45 states have established some form of a BTA policy.Burr, R., Kemp, J., & Wang, K. (2024). Crime, violence, discipline, and safety in U.S. public schools: Findings from the School Survey on Crime and Safety: 2021–22 [NCES 2024-043]. U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2024043 (accessed 02/25/2025); National Center for Education Statistics. (2024). School pulse panel. U.S. Department of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/spp/results.asp (accessed 02/25/2025).

BTA Systems in Schools

BTA systems aim to identify, assess, and manage the threat of targeted violence, with the ultimate goal of intervening to prevent such violence through the use of appropriate student supports. BTA systems in schools were introduced by federal initiatives developed after the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School in Littleton, CO. Since then, the primary BTA models that states have adopted or referenced in their legislation or policies are federal models from the Federal Bureau of Investigation and from the National Threat Assessment Center (NTAC), the Comprehensive School Threat Assessment Guidelines (CSTAG) model, and the Salem-Keizer model. All models encourage a process to define what constitutes a serious threat, establish a multidisciplinary team, and guide how identified threats are handled. They also identify the need for training of threat assessment teams on procedures and highlight the need for all other adults, students, and parents to understand the threat reporting and assessment process.

The federal NTAC model recommends that schools first focus on building a safe and connected school climate to break down the “code of silence” that keeps students from seeking help for themselves or their peers. Evidence supports this: A 2008 NTAC study found that student bystanders who came forward with knowledge of a threat were influenced by positive relationships with one or more adults in the school. Similarly, the CSTAG model, which is the most studied framework, relies on extensive training; uses a flexible, nonpunitive approach that discourages the use of zero-tolerance policies and profiling; and demonstrates how to design and use mental health supports to resolve threatening behavior and intervene proactively to prevent violence. Similar to CSTAG, the Salem-Keizer guidelines provide steps for BTA teams to take, beginning with answering a series of questions to determine whether the threat is unfounded or necessitates further assessment and action. These guidelines also indicate that the BTA should be initiated by a school administrator and either a school counselor or a school resource officer trained in the school’s process and protocol, then extended, if needed, to a broader, communitywide team.

Despite the guidance from these BTA models, there are many districts and schools that have adopted BTA practices but do not follow any of these specific models. Although BTAs are intended to diagnose and provide supports, they are used within school systems that are often accustomed to treating students who are viewed as problematic with exclusionary discipline tactics such as suspension, expulsion, or law enforcement action. Where BTAs have been introduced in settings with inadequate staff and training, these kinds of outcomes have been reported. As a result, concerns have been raised about the outcomes of poorly designed or enacted BTAs, which may target and potentially traumatize the most vulnerable students, including through the exclusion and criminalization of historically marginalized students. On the other hand, higher quality implementation of carefully designed and supported BTAs has been found to increase student supports and decrease levels of and disparities in disciplinary actions. With these concerns and questions, we examine the research evidence on BTAs being used in schools.

Concerns About Behavioral Threat Assessments

Risks About Potential Biases When Implementing BTA Systems

Outside the context of threat assessments, research continues to show that Black students are suspended at higher rates than their peers, and those disparities are further exacerbated for Black students with disabilities. Research has also found that racial disparities in suspensions are strongly associated with differential treatment of students, not differences in student behavior.

These trends can influence the implementation of BTAs. A 2018 analysis of the literature on BTAs revealed that very little attention is paid to understanding how implicit bias may impact the BTA referral process. This finding has contributed to concerns that BTAs, when implemented without careful attention to bias, can lead to the same disparities in exclusionary discipline for and criminalization of historically marginalized students.

Risks Associated With Poorly Implemented BTAs

Although BTAs are required or encouraged in most states and are reportedly used in nearly all districts, concerns have been raised about the outcomes of poorly designed or enacted BTAs. In particular, there are concerns about their likelihood of targeting and potentially traumatizing the most vulnerable students if they are used in punitive rather than supportive ways.

Examples of investigative explorations into how threat assessments are being implemented in schools include the following findings:

- A Texas Observer investigation found that only half of Texas school districts had BTA teams that included members with the required areas of expertise. They also found that only 31% of districts had trained team members and 14% were not conducting BTAs according to Texas law.

- A ProPublica investigation in Tennessee similarly found that threat assessments were being inconsistently carried out. In the absence of appropriate assessments and because of additional laws, BTAs were sometimes leading to harsh consequences for students.

- An investigation into the use of threat assessments in Albuquerque Public Schools by Searchlight New Mexico found that special education students and Black students were disproportionately referred for BTAs for 3 consecutive school years ending in 2018–19.

These investigations have raised concerns about the potentially negative impacts BTAs can have on students if implemented poorly and without appropriate training.

Concerns About the Focus on Law Enforcement Officials

BTAs are intended to provide school staff with a systematic approach to determine whether a threat is serious or not and to intervene only when a threat is determined to be serious and the student has access to the means to perpetrate an act of violence. In most cases, BTAs are meant to respond to threats of violence by intervening with appropriate supports—including peer support programs, counseling, and mental health care—before the issues escalate.

However, concerns have been raised about the inclusion of a law enforcement official or SRO as part of the BTA team from the start, which is required in all the major BTA models being used across the United States. Research finds that:

- the presence of SROs on campuses has limited effects on school safety and can lead to more severe disciplinary actions, particularly for Black students and students with disabilities, as well as lower student outcomes; and

- the more security measures a school employed, including the presence of law enforcement officers during the school day, the higher the rates of suspensions and disparities in suspension rates between Black and White students.

Profiling students instead of focusing on threats has the potential to harm students, particularly Black students and students with disabilities, as the available accounts show. It is with these concerns in mind, and the understanding that they must be central to any discussion on BTAs, that we examine the research evidence on BTAs as they are currently being used in schools.

Existing Evidence on BTA Models

A growing body of literature describes school-based threat assessment practices and procedures. The large majority of studies to date have focused on one specific model—CSTAG—and were conducted by researchers at the University of Virginia (where the model originated). A small number of studies have focused on other specific BTA models

Many implementation studies on BTA systems, mainly using the CSTAG model, focus on schools that received training supports from expert trainers, which may not always be available to schools at scale. Under those conditions, findings suggest that BTA training can lead to changes in beliefs and knowledge, such as increased ability to accurately assess a threat, decreased support for zero-tolerance policies, and a better awareness of the goals of threat assessment. However, research also reports challenges around providing the necessary training needed in many schools.

Overall, the research on BTAs suggests that a focus on using problem-solving practices that aim to provide appropriate interventions in response to threats can begin to move the needle on better supporting students and reducing automatic exclusionary discipline practices. In summary, the research on outcomes to date finds the following:

- Standard 1-day trainings that have been implemented across multiple states by the CSTAG team result in significant changes in participants’ beliefs and abilities to identify substantial versus minor threats, based on pre- and post-training surveys.Allen, K., Cornell, D., Lorek, E., & Sheras, P. (2008). Response of school personnel to student threat assessment training. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 19(3), 319–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243450802332184; Stohlman, S., Konold, T., & Cornell, D. (2020). Evaluation of threat assessment training for school personnel. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 7(1–2), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/tam0000142

- Variability in implementation exists, with a need for more training, more staff allocated toward these models, and better data collection efforts.Maeng, J. L., Cornell, D. G., & Warren, E. (2021). Threat assessment training and implementation needs survey state report. School of Education and Human Development, University of Virginia. https://education.virginia.edu/sites/default/files/2023-06/yvp_fl-threat-assessment-training-implementation-needs-survey-state-report_03-30-2021.pdf

- Descriptive studies of BTA models are largely based on the CSTAG model, which is inclusive of training and a focus on mental health supports. Findings from these studies suggest that well- supported implementation of CSTAG may still be susceptible to existing biases, particularly in the rates of referrals for a threat assessment for students of color—especially Black students—and students with disabilities.Cornell, D., Maeng, J. L., Burnette, A. G., Jia, Y., Huang, F., Konald, T., Datta, P., Malone, M., & Meyer, P. (2018). Student threat assessment as a standard school safety practice: Results from a statewide implementation study. School Psychology Quarterly, 33(2), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000220 Despite this, the supplementary actions indicate a reduction in biased exclusionary practices and increases in school climate. These include:

- fewer suspensions, expulsions, and law enforcement actions in schools using CSTAG than in those using a general threat assessment approach; and

- students reporting less bullying, greater willingness to seek help, fairer discipline, lower levels of student aggressive behaviors, and more positive perceptions of school climate in schools using CSTAG than students in schools using either a general BTA approach or not using BTAs at all.

- fewer suspensions, expulsions, and law enforcement actions in schools using CSTAG than in those using a general threat assessment approach; and

- Two studies find more causal relationships whereby implementing the CSTAG model leads to reductions in exclusionary disciplinary actions and bullying infractions and to increases in counseling support.Cornell, D., Allen, K., & Fan, X. (2012). A randomized controlled study of the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines in Grades K–12. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087378; Cornell, D., Gregory, A., & Fan, X. (2011). Reductions in long-term suspensions following adoption of the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines. NASSP Bulletin, 95(3), 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192636511415255 They also maintain no disparities in who is referred for a threat assessment or who receives a disciplinary action. Students who made threats of violence in schools using the CSTAG model were significantly more likely to receive counseling services and a parent conference than students in control schools, while students in the control group were significantly more likely to receive a long-term suspension or be transferred to a different school.

- Among CSTAG schools, those with higher compliance scores showed the greatest reductions in long-term suspensions and increases in counseling provided.Cornell, D., Allen, K., & Fan, X. (2012). A randomized controlled study of the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines in Grades K–12. School Psychology Review, 41(1), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2012.12087378

As the nonacademic literature suggests, many schools and districts across the nation are implementing various other models that are not supported by the same level of training or emphasis on intervening with appropriate supports as CSTAG. Thus, more research is needed to truly understand how BTAs are being implemented nationally and what their results look like. Indeed, in one recent research paper studying a BTA model, the authors noted, “Threat assessment teams must make every effort to make decisions that are fair and unbiased and to recognize the potential for implicit biases in their work.” It is crucial that threat assessment systems are designed and implemented in ways that counteract these biases.

Considerations and Concerns When Using School- Based BTA Systems

As in many educational programs, research finds a gap between the conceptualization of threat assessment systems and their implementation. As a consequence, educators and civil rights advocates have expressed concerns about whether threat assessment systems may profile and punish vulnerable groups of students rather than identify and help those needing support. These concerns must be considered as BTA systems become increasingly prevalent across the country. For BTA systems, which are now required in most states and districts, to be positive and protective of students and schools, the research suggests that several elements are key.

Consideration 1: Rooting BTAs Within a Positive School Climate

Successful violence prevention programs rely on creating safe and supportive schools that offer strong foundations of support for student mental health and well-being. Yet, while BTA models are built on this relationship, few state policies clearly make the connection between supporting a positive school climate and successfully deterring threats and acts of violence. Research demonstrates how positive relationships serve as a foundation for learning, mental health, and emotional wellness—particularly when students feel welcome and connected to their school communities—and help prevent physical violence and bullying. Although supportive, relationship-centered schools are the foundation for school safety, policymakers often treat physical safety measures and psychological safety measures as two separate entities. More must be done to ensure that any school violence prevention strategy—including BTAs—supports strong relationship-centered schools and integrated supports.

Consideration 2: Creating and Training BTA Teams Appropriately

Policies and procedures for BTA implementation vary widely across states and districts, leaving room for significant implementation issues to arise. Each of the major school BTA models clearly identifies the need for appropriate threat assessment training as a key component of high-quality implementation, yet a number of studies have found challenges with the state of BTA training in many schools, as well as concerns about the adequacy of staffing of these teams. Little is known about the composition of teams across schools and whether, for example, they include key staff members like counselors, mental health professionals, or special education teachers when the BTA involves a student with a disability.

Consideration 3: Designing BTA Systems to Problem Solve, Not Criminalize

For any school safety strategy to be effective, it needs to be implemented with fidelity and embedded within both a strong system of support for students and comprehensive efforts to prevent violence. The purpose of BTAs as a problem-solving, violence prevention tool—not as a means to exclude and criminalize students—also should be communicated clearly to the entire school community. While BTAs are intended to diagnose and provide supports, they may reinforce exclusionary practices when used within school systems that already rely on those practices. The inclusion of law enforcement at the earliest stages of a threat assessment raises concerns about potential negative impacts on students involved in the BTA process. More research is needed on the role of school resource officers or law enforcement in BTAs, and clear guidelines should be put in place for when and how it is appropriate to include them in the BTA process and with what prior training.

Consideration 4: Equipping Schools With Needed Counseling and Mental Health Supports

The existing evidence suggests that many schools may lack the appropriate mental health supports that are key to the BTA approach, especially access to mental health counselors and services. Nationally, schools have about half as many counselors and school psychologists as recommended by professional associations, with schools that serve more students of color and students from low-income families being the least likely to have adequate personnel supports in most states. Without proper implementation processes, appropriate team members, and links to supports, schools may be operating a hollow system that fails to understand why young people make threats and thus respond inappropriately when they do.

Consideration 5: Collecting and Reporting Useful BTA Data to Support Continuous Improvement

Early research indicates that BTA data, even when mandated by law, are not always collected in a consistent, sufficiently detailed manner. In total, only 7 of the 20 states mandating school BTAs require data on BTAs to be collected and reported, and even fewer require a full breadth of data (e.g., number of students referred for BTAs disaggregated by student demographic, number of threats deemed to be serious, actions and outcomes of BTAs). Moreover, no state mandates that those data be made publicly available. It is critical that data be reported accurately to understand how these systems actually work in schools, whether they are leading to greater or less safety in schools, if there are biases in implementation, and whether they are associated with more or fewer discipline disparities.

Conclusion

In an environment where resources, time, and capacity are in limited supply, states and school districts benefit when they invest in evidence-based strategies and research-backed supports that promote physically and psychologically safe school environments. Though evidence indicates that well-designed and well-implemented BTAs can be part of a successful violence prevention strategy, there is far more to learn about what will enable these conditions in schools.

We encourage policymakers to ensure schools are well equipped to provide high-quality training and intervention supports to students receiving BTAs, especially access to mental health professionals and services. Schools should also be supported in creating positive school climates, which are the backbone of BTAs and school safety strategies in general. And, in order to have an accurate picture of how BTAs are being implemented and how they are affecting students, it is critical for data reporting and collection to be required and supported by states.

Keeping Schools Safe: The Impacts of Behavioral Threat Assessments on Student and School Safety (brief) by Jennifer L. DePaoli and Stacy B. Loewe is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Core operating support for LPI is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.