Building a Well-Qualified Transitional Kindergarten Workforce in California: Needs and Opportunities

Summary

In 2021, California committed to making transitional kindergarten (TK)—a school-based preschool program initially designed for older 4-year-olds—available for all 4-year-olds by 2025–26. As TK becomes universal, California will need to greatly expand the early learning workforce. This brief provides estimates of how many TK teachers California will need; describes the potential supply pools that could meet this demand; outlines pathways into the profession; and offers recommendations to help stabilize, support, and expand the entire early childhood workforce.

The report on which this brief is based, which includes county-level estimates for TK teacher demand, can be found here.

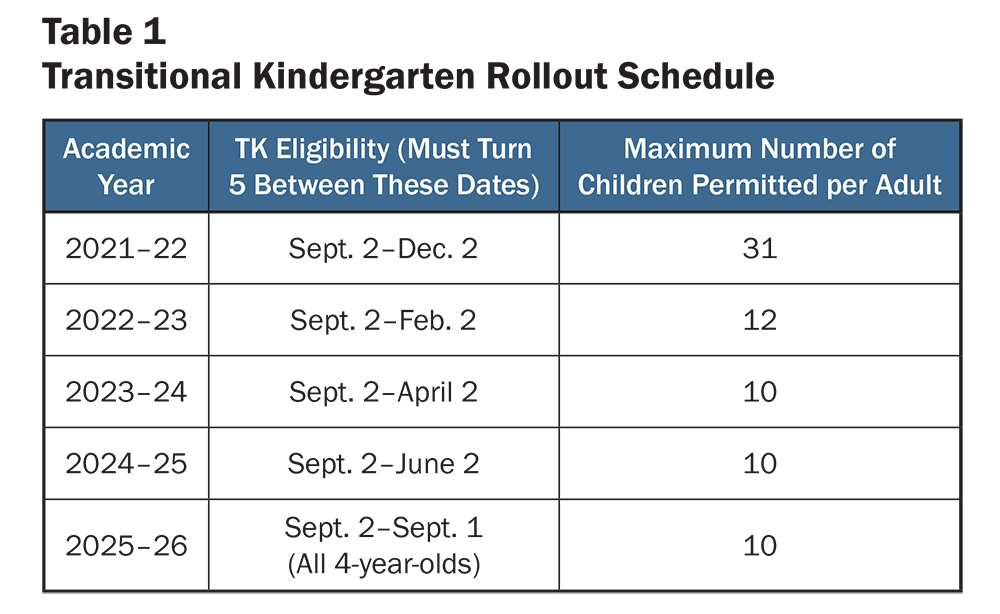

In 2021, California made historic changes to its early learning system by committing to universal preschool for all 4-year-olds by 2025–26. The biggest expansion is through transitional kindergarten (TK), a district-based preschool program. When it was created in 2010, TK was only funded for 4-year-olds who just missed the kindergarten eligibility cutoff of September 1; under the new law, age eligibility will gradually expand over a 5-year period. (See Table 1.) California also made new investments in the California State Preschool Program (CSPP), a program for income-eligible 3- and 4-year-olds in school and community settings.

Source: California Education Code § 48000 (2021).

To ensure the quality of new preschool investments, California must recruit and prepare a sufficient number of qualified teachers in TK and other early childhood programs—a challenge given the rapid expansion of these programs, which has been accompanied by reduced ratios of adults to children. This challenge has been even greater during the COVID-19 pandemic, with school districts and early childhood programs facing significant staffing shortages. Preschool expansion presents an opportunity to make significant improvements to preparation, professional development, compensation, and working conditions for educators working with 3- and 4-year-olds, who, like other early educators, have historically had uneven access to quality preparation and professional learning and worked for very low pay. It also presents an opportunity to diversify the TK workforce by bringing in current early educators, who are much more linguistically, racially, and ethnically diverse than their TK–12 counterparts.McLean, C., Austin, L. J. E., Whitebook, M., & Olson, K. L. (2021). Early childhood workforce index 2020. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley.

To help California policymakers understand the scope of the state’s early childhood education (ECE) workforce needs, the report on which this brief is based provides estimates for how many TK teachers California will need through 2025–26. It then discusses potential pools of candidates to meet demand; suggests ways to support a diverse, well-prepared workforce in TK and other early childhood programs; and offers recommendations for state policymakers.

Projecting the Need for TK Teachers

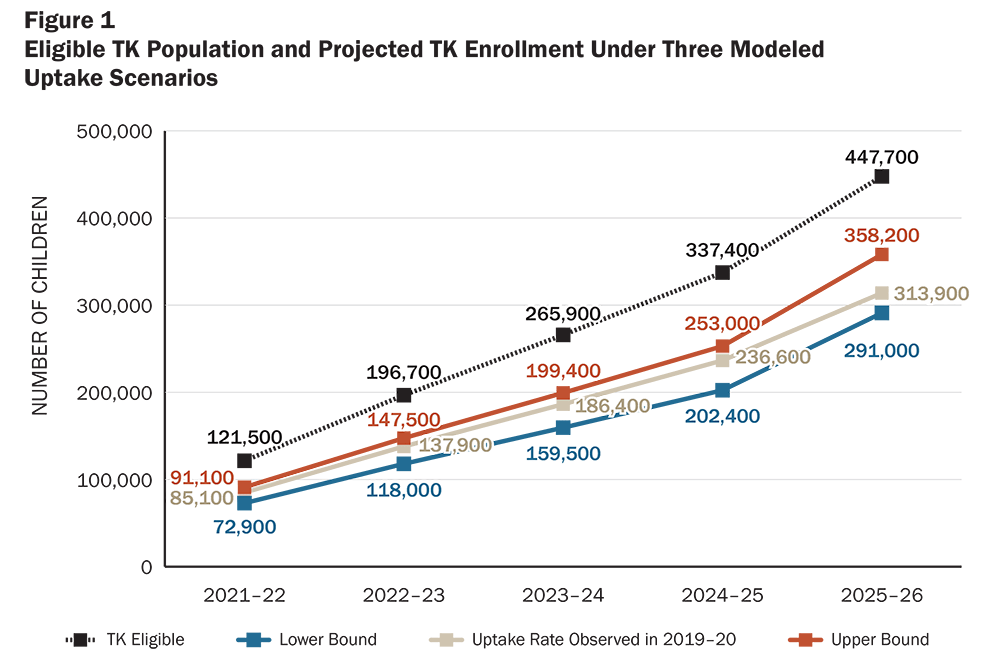

To estimate the total number of lead and assistant TK teachers that California will need by 2025–26, we use historic TK enrollment data from the California Department of Education and population projections from the California Department of Finance, among other sources. Given the uncertainty in the number of eligible children who will enroll in TK, we created three primary estimates covering a range of uptake assumptions. The first is a conservative lower bound of 65% uptake in 2025–26, rising from 60% in earlier years, based on uptake in the early years of TK implementation and adjusting for potential reduced uptake due to COVID-19. The second is a midrange option, the observed uptake rate for TK in 2019–20 applied through 2025–26 (about 71% statewide). The third is an upper-bound uptake of 80% in 2025–26, increasing from 75% in earlier years, based on evidence from universal preschool programs in other states.

Our estimates assume that each class will be staffed by one lead and one assistant teacher. We further assume an initial class size of up to 24 children to meet the state’s 12:1 child–adult ratio and, starting in 2023–24, a class size of up to 20 children to meet the state’s 10:1 ratio requirement. We assume that classes are filled at 90% capacity, on average, resulting in an average of 21.8 children per class through 2022–23 and 18.2 children per class after 2023–24. Because the state does not currently have data on the number of TK teachers employed by districts, we also estimate the number of teachers employed in our baseline year of 2019–20 based on the number of children enrolled in TK that year. (See the full report for the detailed methodology.)

Based on these data and assumptions, we find that:

- In 2025–26, more than 300,000 children are likely to enroll in TK. We estimate that between 291,000 and 358,000 children are likely to enroll in TK in 2025–26. If children enroll at pre-pandemic enrollment rates (71% statewide), TK enrollment will grow fourfold between 2019–20 and 2025–26. (See Figure 1.)

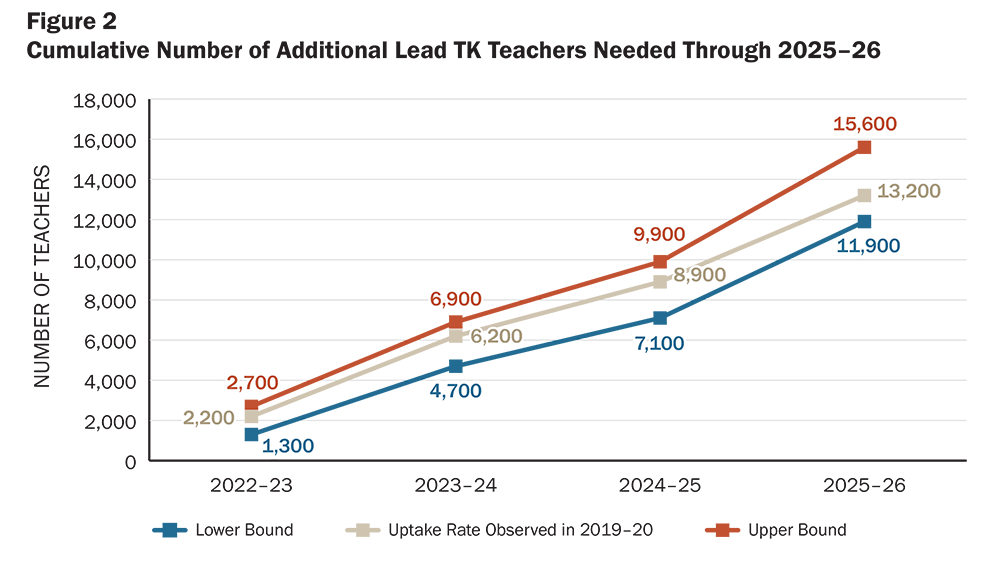

- To meet this demand, districts will need to hire between 11,900 and 15,600 additional lead teachers by 2025–26, above and beyond the approximately 4,100 TK teachers we estimate were needed in 2019–20. (See Figure 2.)

- California will need between 16,000 and 19,700 assistant TK teachers in 2025–26. Most classes will be required to have an assistant teacher to meet child–adult ratios of 12:1 in 2022–23 and 10:1 in 2023–24. We expect the total demand for assistant TK teachers to be about equal to the total demand for lead TK teachers.

- Growth in TK teacher demand will not be linear over time; particularly sharp increases are projected for 2023–24 and 2025–26. We anticipate that the largest increase in teacher demand will come in 2023–24—when child–adult ratios will drop from 12:1 to 10:1—and in 2025–26, when the full cohort will become eligible for TK (adding 3 months of eligibility, compared to adding 2 months of eligibility in prior years).

- County differences in TK uptake rates and population size translate into varying hiring expectations. TK uptake has historically varied greatly across counties. Counties that have had low TK uptake will need relatively more teachers to meet demand at full implementation. The five largest counties alone (Los Angeles, San Diego, Orange, Riverside, and San Bernardino) account for over half of the total estimated increased demand by full implementation.

Sources: California Department of Education. Transitional kindergarten data from 2015–16 to 2019–20. https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/ad/fstkdata.asp; California Department of Finance. County population projections (2010–2060): P-2B county population by age. https://dof.ca.gov/Forecasting/Demographics/projections/; California Education Code § 48000 (2021).

Sources: California Department of Education. Transitional kindergarten data from 2015–16 to 2019–20. https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/ad/fstkdata.asp; California Department of Finance. County population projections (2010–2060): P-2B county population by age. https://dof.ca.gov/Forecasting/Demographics/projections/; California Education Code § 48000 (2021).

Building a Qualified, Diverse TK Workforce

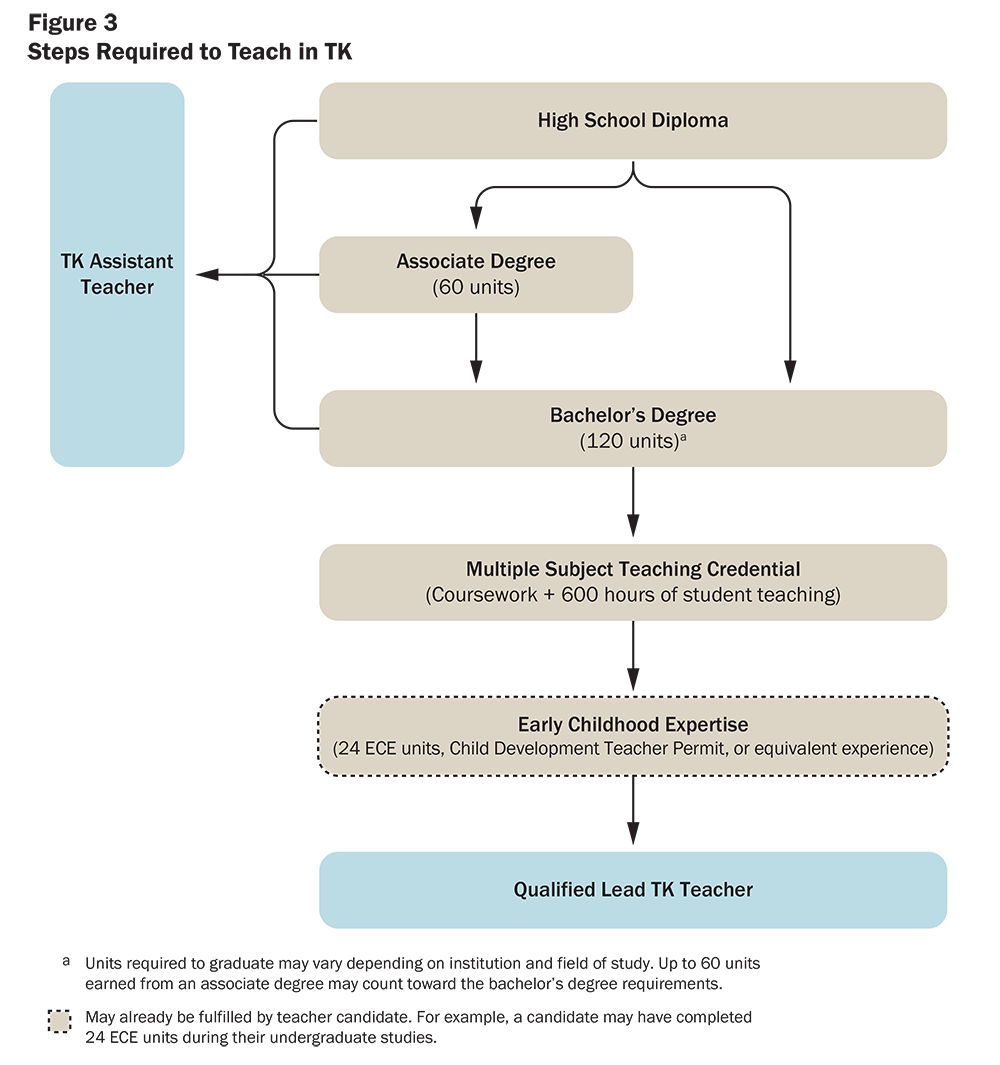

The teacher demand projections described above show that California has an urgent need for new lead and assistant TK teachers and that districts will need to fill positions quickly. TK teacher qualifications require more formal education than other early childhood programs. To date, lead TK teachers must have a Multiple Subject Teaching Credential, which requires a bachelor’s degree, a year of coursework related to teaching kindergarten through grade 8, 600 hours of clinical teaching experience, and a passing score on a teacher performance assessment, among other requirements. Districts receiving state funding for TK also must ensure lead TK teachers complete 24 college units in ECE, hold a Child Development Teacher Permit, or have equivalent experience, as determined by the employer.California Education Code § 48000(g) (2021). Candidates may soon be able to meet TK requirements instead through a new preschool to 3rd grade (P–3) credential. (See “Developing a New P–3 Credential for California.”) Lead teachers working in state-funded preschools must have or be working toward a Child Development Teacher Permit, which requires 24 units of ECE, 16 general education units, and 175 days of experience working in an ECE program. A college degree is not required, but as will be discussed below, a large share of these teachers hold a bachelor’s degree.

To work as an assistant TK teacher, an individual need only hold a high school degree and either pass an assessment demonstrating basic skills and pedagogical knowledge, complete 48 college units, or have an associate degree. (See Figure 3.) In contrast, assistant teachers in ECE programs must hold a high school diploma and complete at least 6 units of ECE coursework.

Below we describe how different candidate pools could be prepared to meet the TK workforce qualifications.

Developing a New P–3 Credential for California

In June 2022, the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) decided to move forward with the development of an ECE Specialist credential that allows the holder to teach preschool through grade 3. This credential is similar in structure to the Multiple Subject credential in that it requires coursework from an accredited teacher preparation program and 600 hours of clinical experience. However, it has an explicit focus on preparing teachers to work with children from preschool through grade 3. The credential additionally includes a unique set of teacher performance expectations, developed by the CTC and an expert working group, as well as its own set of program expectations. ECE Specialist credentialing coursework may be “stacked” on top of ECE coursework a candidate has already completed (such as coursework to earn a Child Development Teacher Permit). The CTC anticipates that ECE Specialist credential programs will be able to be accredited by early 2023. These changes could improve the relevance of teacher preparation for TK teachers and may be more accessible to experienced early educators than the Multiple Subject credential.

Source: California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2022). Information/action: Proposed authorization statement and credential requirements for the PK-3 Early Childhood Education Specialist credential. https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/commission/agendas/2021-09/2021-09-2a.pdf?sfvrsn=14b325b1_2

Candidates With a Teaching Credential Who Lack ECE Experience

One group of teachers poised to teach TK is composed of teachers currently authorized to teach in elementary schools, including Multiple Subject Teaching Credential holders in California. Out-of-state credential holders are also an important candidate pool, making up 16% of new Multiple Subject credentialed teachers entering the state each year. These teachers may teach TK, and the district may receive apportionment funds for their classrooms if they have an additional 24 units of ECE, a Child Development Teacher Permit, or equivalent experience by August 2023.

Candidates who do not have the required ECE experience could prepare to enter the TK workforce by taking coursework while working in their current positions or holding an internship in a TK classroom. Local education agencies (LEAs) can organize and fund cohorts of teachers to take ECE-focused coursework at partner universities. Programs should consider including clinical supervision and coaching as a key expectation for some of these course units. The courses could be intentionally designed to build toward a master’s degree in ECE for those teachers who choose to pursue it.

Candidates With a Bachelor’s Degree and Early Childhood Experience

Individuals who have a bachelor’s degree and early childhood experience and training but lack a teaching credential are also well positioned to become TK teachers. According to a recent survey by the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, about 41,000 (49%) of current center-based early educators have a bachelor’s degree or higher, including 29,000 teachers who hold a Child Development permit at the teacher level or higher.Williams, A., Montoya, E., Kim, J., & Austin, J. E. (2021). New data shows early educators equipped to teach TK. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. The early educator workforce is more racially and ethnically diverse than the TK–12 workforce, with 66% of center-based teachers identifying as people of color, compared to 39% of TK–12 teachers.Powell, A., Kim, Y., & Montoya, E. (2021). Demographics of the California ECE workforce. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley; California Department of Education. (2020). Fingertip facts on education in California. TK positions are likely to be attractive to early educators since TK wages are nearly double the wages offered by ECE programs.Powell, A., Montoya, E., Austin, L. J. E., & Kim, Y. (2022). Double or nothing? Potential TK wages for California’s early educators. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Another candidate pool is recent graduates of ECE and child development bachelor’s degree programs, with nearly 5,000 degrees conferred each year.LPI analysis of the 2018–19 and 2019–20 Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.) (accessed 01/03/22). Both candidate pools are poised to take facilitated paths into lead TK teacher positions since they have experience working with young children and already meet several requirements needed to earn a credential.

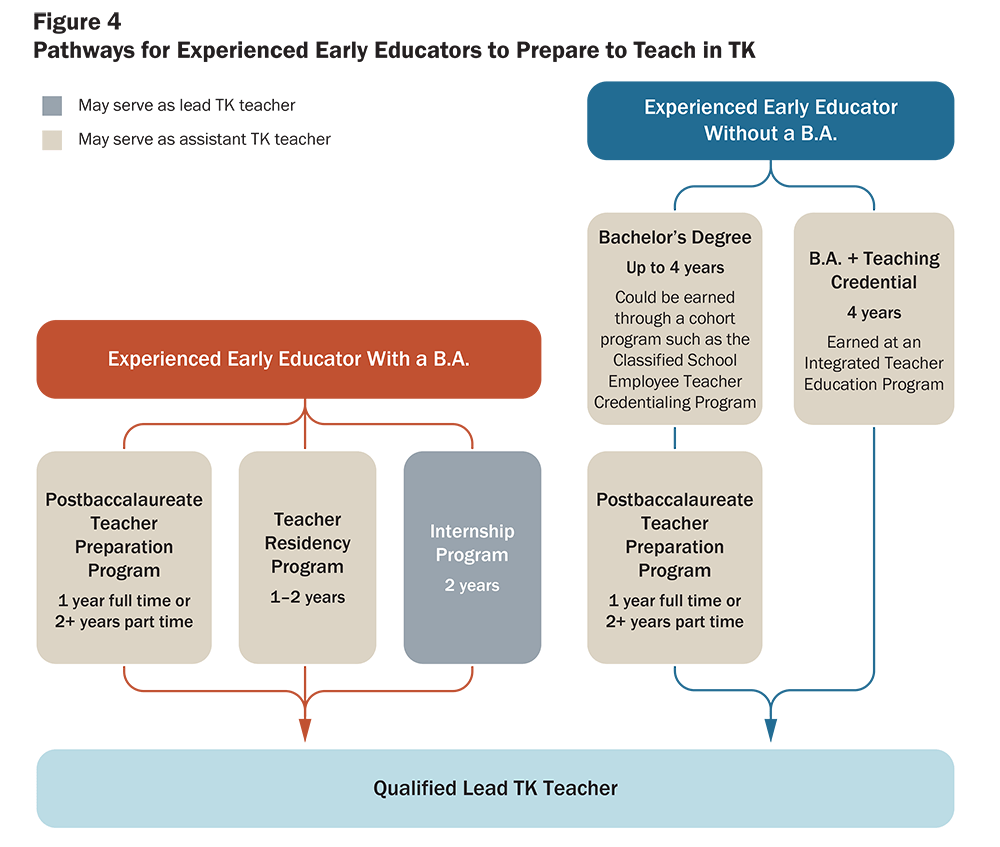

There are three main pathways that are particularly well suited to early educators who need to meet teaching credential requirements for TK. (See Figure 4.) One is teacher residency, a preparation model that could allow candidates to serve in assistant TK teacher positions and be employed while working toward a credential. High-quality teacher residencies integrate credentialing coursework with a clinical placement, with residents working at least half-time in the classroom of an expert mentor teacher. A second is intern credentialing programs, in which candidates work and are paid as the teacher of record while taking coursework. Intern credentials may be issued to teachers in training who have demonstrated basic skills and subject-matter competence but have not yet completed a teacher preparation program or met performance assessment requirements.Teachers may currently show subject-matter competence by completing a specified subject-matter program of study or by passing the California Subject Examination for Teachers (CSET). California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2022). District Intern Credential (CL-707b). A high-quality internship program provides candidates with mentorship as well as academic and financial support. A third path is traditional credentialing programs, which may include full-time, full-year programs as well as programs offered over a longer time horizon with some online coursework that allows candidates to work while studying. Teacher preparation programs may acknowledge previous coursework or teaching experience that candidates have already completed.

Candidates Without a Bachelor’s Degree

Current early educators and classified staff who have early education or teaching experience but do not hold a bachelor’s degree are also potential longer-term candidates for TK teacher positions. Of the 83,000 center-based educators in California’s early learning workforce, about 26% have an associate degree and 25% have some college or less.Personal email with the Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. (2021, October 27). Among lead center-based teachers, 25% have an associate degree and 20% have some or no college. Kim, Y., Austin, L. J. E., Montoya, E., & Powell, A. (2022). Education and experience of the California ECE workforce. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. Another potential pool of TK teachers and assistant teachers is recent graduates of ECE-related associate degree programs. In 2020–21, nearly 6,000 associate degrees in ECE were conferred in California,Degree majors include child development and early childhood education. Degree types include Associate in Science for Transfer (2,487), Associate in Arts for Transfer (1,102), Associate of Science (1,225), and Associate of Arts (1,002). California Community Colleges Chancellor’s Office. (n.d.) Management Information Systems Data Mart. (accessed 01/13/22). more than half of which were transfer degrees that allow the holder to enter a bachelor’s degree program with junior standing.Candidates without a degree for transfer may be able to transfer many of their college credits toward a bachelor’s degree, although the number of credits counted will vary based on a candidate’s prior coursework and the bachelor’s degree program requirements. Paraprofessionals, teacher aides, and expanded learning staff are also good candidates for programs that will prepare them for TK teacher positions, having demonstrated an interest in working with children.California employed 155,690 teaching assistants (excluding postsecondary) in 2020, with a mean salary of $37,260. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2022). Occupational employment and wages, May 2021: 25-9045 teaching assistants, except postsecondary.

These candidates could continue working in their current positions or be employed as assistant TK teachers while working toward a degree and credential. The traditional pathway for these candidates would be to pursue a bachelor’s degree and then a teaching credential. Having candidates take coursework in cohort-based programs may improve retention. These groups are also good candidates for integrated teacher education programs, which build on coursework taken in community college and allow candidates to earn a bachelor’s degree and teaching credential in 4 years. (See Figure 4.)

New candidates that districts might tap to fill assistant TK teacher positions and teach in other ECE programs include recent high school graduates, parents of school-age children who are reentering the workforce, and career changers. Districts might build or expand dual enrollment pathways that allow students to take ECE-related coursework for college credit while in high school and support pathways to a bachelor’s degree and a teaching credential. While these candidates would not fill lead TK teacher positions in the short term, they are an important part of building a long-term ECE assistant teacher and teacher pipeline.

Funding Teacher Pathways Into TK

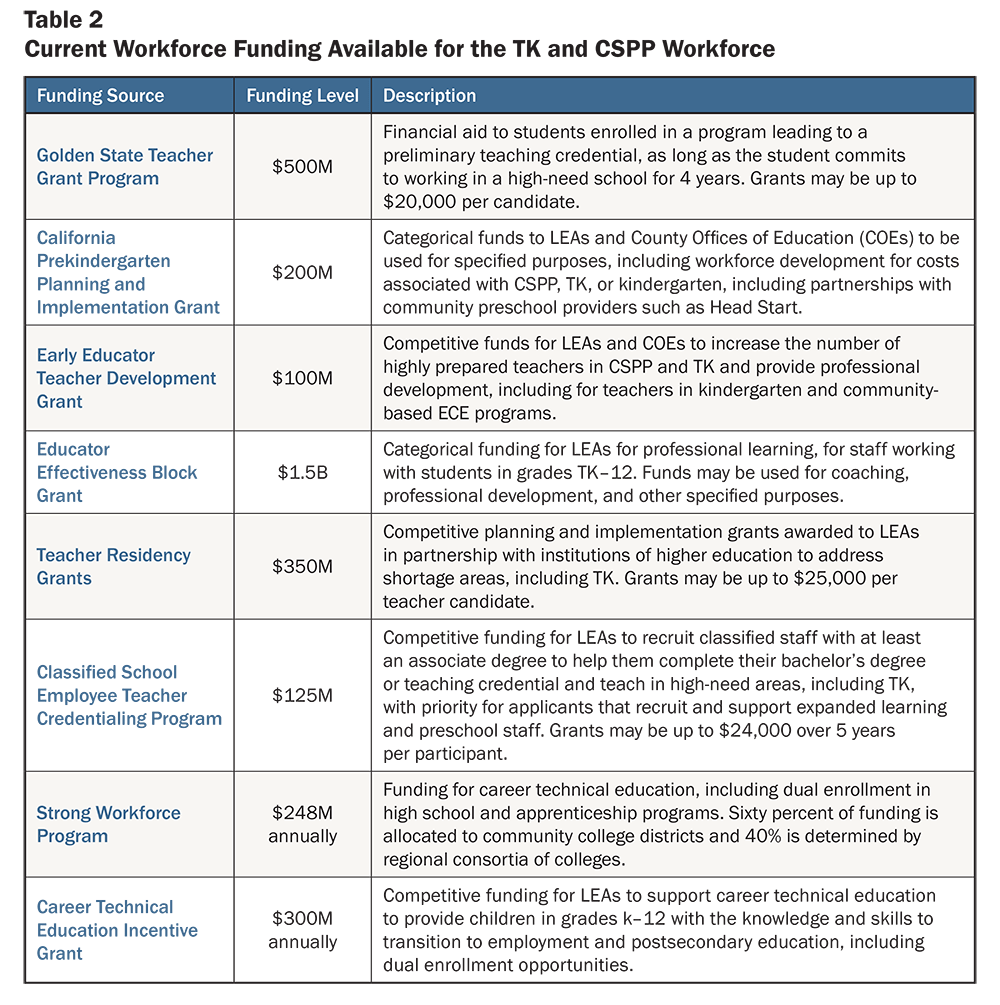

State policymakers have recently made several funding sources available to help LEAs develop teacher pathways for TK and other ECE programs. Some funding goes directly to candidates themselves, and most other funding sources are awarded directly to LEAs (school districts and county offices), including two grants specific to the TK and CSPP workforce. (See Table 2.)

Beyond TK: Supporting the Broader ECE Workforce

When the legislature and the governor expanded TK, they expressed intent to maintain families’ access to the California State Preschool Program, Head Start, and other early learning programs and made several investments in these programs, including increased funding rates for child care and state preschool. Still, lead TK teacher positions to date have offered much better compensation and working conditions than most other early childhood teaching positions, making it likely that many qualified ECE staff will shift into TK.Powell, A., Montoya, E., Austin, L. J. E., & Kim, Y. (2022). Double or nothing? Potential TK wages for California’s early educators. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. If many early educators leave other ECE programs for TK, it may have significant implications for staffing and quality in the programs they leave. Policymaking to expand the TK workforce should therefore consider solutions to support and expand the entire ECE workforce, including teachers of infants, toddlers, and 3-year-olds.

Recommendations

California will need to take steps to produce an adequate supply of effective early educators in the short and long term. State policymakers can take the following six steps to stabilize, support, and expand the broader early childhood workforce and build pathways for racially, linguistically, and culturally diverse educators.

- Clearly map out and communicate career pathways into TK and other ECE programs. California’s state agencies, including the California Department of Education and California Commission on Teacher Credentialing, should clarify what is required to teach in ECE programs and make pathways easy for all interest holders to understand. In addition, state agencies should clearly communicate how individuals at different stages of their careers or preparation can access scholarships and other financial supports. Each of California’s counties will additionally need to coordinate and communicate its own workforce development pathways, since counties each have a unique set of supports for ECE educators to advance their careers. This process will require strong collaboration on a rapid time scale between LEAs, institutions of higher education, early childhood providers, unions, resource and referral agencies, and other community partners. County offices of education may be well situated to support this collaboration.

- Develop high-quality pathways into teaching TK that are tailored to the needs of experienced early educators. Existing pathways to teaching, including residency programs and internships, were developed primarily for candidates without prior teaching experience. Ideally, California will support pathways to a teaching credential for experienced early educators that give credit for their knowledge and expertise. Ensuring a straightforward pathway for early educators is a matter of practicality—to meet the urgent need for TK teachers—but also a matter of equity, given that the ECE workforce is composed primarily of women of color who have historically earned very low wages. State policymakers might therefore consider enabling and encouraging pathways that accept equivalencies for coursework that candidates have already completed and acknowledge clinical expertise for educators who can demonstrate teaching competence—for example, on a performance assessment. Candidates should also have access to funding and support to take additional coursework they may need for the new credential, and such coursework should be made readily available.

- Provide grants to institutions of higher education to develop new credentialing programs for P–3 educators. To develop new credentialing programs specific to early childhood educators, institutions of higher education will need to make several up-front investments, including hiring new staff, developing curriculum and articulating coursework, and recruiting candidates. Institutions of higher education will also need to foster collaboration between teacher preparation programs and ECE-related degree programs, including at community colleges. The state could offer grants to institutions of higher education, prioritizing programs that make coursework accessible to candidates. Policymakers might prioritize grants for programs in geographic areas where relatively fewer early educators have a bachelor’s degree.

- Set appropriate requirements for assistant TK teachers to ensure these educators are prepared to support learning and development. Although assistant teachers in many of California’s preschool programs are required to hold a Child Development Assistant or Associate Teacher Permit, assistant TK teachers are not currently required to have any early childhood knowledge, experience, or other training. Assistant teachers in TK classes might be held to the same education requirements as associate teachers in California State Preschool Program classes; that is, 12 units of ECE coursework or the equivalent. Given the implementation pressures LEAs are facing to staff classrooms, assistant teachers might be given several years to meet this requirement, with opportunities to take coursework while working.

- Make new investments in the broader early educator workforce, beyond TK. As TK expands, ECE teachers may move into better compensated, better supported TK jobs. Child care and preschool programs will also need a growing supply of staff to run a high-quality program. New investments are needed to expand the workforce in the California State Preschool Program, Head Start, and other ECE programs. The legislature could reinstate funding for the $195 million Early Educator Workforce Pathways Grant that was funded in the 2020 budget but later redirected to COVID-19 relief. In addition, the legislature could fund expansion of dual enrollment of high school students in ECE coursework through the Golden State Pathways program. New investments should be coupled with continued efforts to ensure that ECE programs have enough funding to offer competitive wages and benefits.

- Collect new data to monitor ECE workforce needs. There are currently significant gaps in our knowledge about the ECE workforce, including how many teachers are currently teaching TK or what backgrounds they have. The state also does not collect workforce data on its other early childhood programs, including CSPP, making it impossible to track staffing qualifications, demographics, existing shortages, turnover, and attrition of ECE educators. California should improve TK data collection and begin to collect workforce data from its state-subsidized early childhood programs, starting with CSPP, to ensure policymakers understand and can address ECE staffing needs and gaps across the state.

Building a Well-Qualified Transitional Kindergarten Workforce in California: Needs and Opportunities (research brief) by Hanna Melnick, Emma García, and Melanie Leung--Gagné is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Ballmer Group, the Heising-Simons Foundation, and the Packard Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the author and not those of our funders.