California’s Students in Foster Care: Challenges and Promising Practices

Summary

California’s foster care system included approximately 47,000 students in grades k–12 in 2018–19. Students in foster care face a range of challenges to their educational success, including an increased likelihood of having experienced trauma, higher rates of suspension and absenteeism, and higher rates of school mobility. As a consequence, they typically experience lower academic outcomes and graduation and college-going rates. This brief analyzes data on educational outcomes of students in foster care, identifies challenges to supporting them, highlights promising practices, and presents policy recommendations for better serving students in foster care.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

The foster care system in California is a key part of the state’s system for protecting vulnerable children from harm. Its goals are to ensure children’s safety, protect children from maltreatment and neglect, place children in family-like settings, and provide families support so children can safely return home whenever possible. The reasons for entry into the foster care system are multiple, complex, and often intertwined with the social and environmental challenges associated with poverty. The experiences of students in foster care can impact their education, such as multiple school moves and disruption of community ties. As processes and policies within a state’s education system can impact students’ experiences in the foster care system and vice versa, these two systems share a connection.

This brief examines the school conditions and education outcomes for students in foster care; the organizational, logistical, and data challenges to providing coordinated support; and promising practices for future supports. It is intended to provide additional information to stakeholders about the education experiences of California students living in foster care and the issues the education system faces in meeting their needs.

California Students and the Foster Care System

In 2018–19, approximately 47,000 California students in grades k–12 were in foster care (around 0.7% of the student population).California Department of Education. (n.d.). 2018–19 suspension rate [Discipline report]. DataQuest. (accessed 04/15/21); Cal. Ed. Code § 42238.01(b). While children and youth living under a family maintenance plan are not traditionally considered “in foster care,” California education law defines these individuals as foster youth. The majority of students in foster care were Latino/a (55%), which matches the percentage of Latino/a students in the statewide student population,California Department of Education. (n.d.). 2018–19 suspension rate [Discipline report]. DataQuest. (accessed 04/15/21). but African American students, at 18% of the foster care population, were disproportionately represented,Harp, K. L. H., & Bunting, A. M. (2020). The racialized nature of child welfare policies and the social control of Black bodies. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 27(2), 258–281; Krase, K. S. (2013). Differences in racially disproportionate reporting of child maltreatment across report sources. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 7(4), 351–369; Kim, H., & Drake, B. (2018). Child maltreatment risk as a function of poverty and race/ethnicity in the USA. International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(3), 780–787; Pelton, L. H. (2015). The continuing role of material factors in child maltreatment and placement. Child Abuse & Neglect, 41, 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.08.001 as were students identifying as LGBTQ (30% of foster care youth)Baams, L., Wilson, B. D., & Russell, S. T. (2019). LGBTQ youth in unstable housing and foster care. Pediatrics, 143(3). and students eligible for special education services (31%).California Department of Education. (n.d.). 2018–19 suspension rate [Discipline report]. DataQuest. (accessed 04/15/21).

Students in foster care often face complex challenges arising from the instability of their living arrangements. Although children in foster care have a right to remain in their schools of origin, removal from the family home or changes in foster care placement can cause students to move schools or even districts. As a result, children in foster care are often faced with the double burden of adjusting to a new school and a new home situation.

Multiple or unanticipated school moves can interrupt students’ learning progression. On top of navigating new transportation arrangements and a new campus, school changes mean adjusting to new curricula and teachers. Students may have missed some topics or material already covered at their new school, encounter significant differences in teaching styles and teacher expectations, and be less able to take advantage of resources at the new school. Missing, incomplete, or delayed transfer of transcripts, assessments, and attendance information—especially when students change schools midsemester—can result in lost academic credits and challenge the receiving school’s ability to serve transferring students.

Changing schools midyear can also disrupt supportive social relationships. Moving school and home at the same time can involve cutting ties with peer and friend communities, including extracurricular activities or sports. These losses can reduce students’ sense of belonging and level of engagement at school.

The experience of trauma is also a key barrier to students’ educational success. Students in foster care are more likely than their peers to have experienced trauma due to family separation and/or the circumstances that led to being placed in foster care. While many children in foster care exhibit resilience, trauma can take a toll. The experience of trauma can inhibit students’ abilities to concentrate, with consequences for their learning. Behavioral issues that may be symptomatic of trauma, such as attention-seeking actions, can be easily misunderstood as intentional wrongdoing and result in exclusionary discipline and reduce access to learning opportunities. In all, the academic and social-emotional experiences of children in foster care are impacted by myriad circumstances that arise concurrently both in and out of school.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the social and environmental challenges facing students. Because many schools, child welfare agencies, courts, and other businesses and agencies closed for much of the 2019–20 and 2020–21 school years, students in foster care experienced reduced access to in-person education and supports. As the state and schools work to recover from the pandemic, sustained attention will be necessary to ensure these students have access to the services they need to succeed.

Educational Experiences of Students in Foster Care

To investigate the educational experiences of students living in foster care, we analyzed data from 2018–19 from the California Department of Education, including enrollment records, absenteeism and suspension rates, and achievement data.

School Mobility

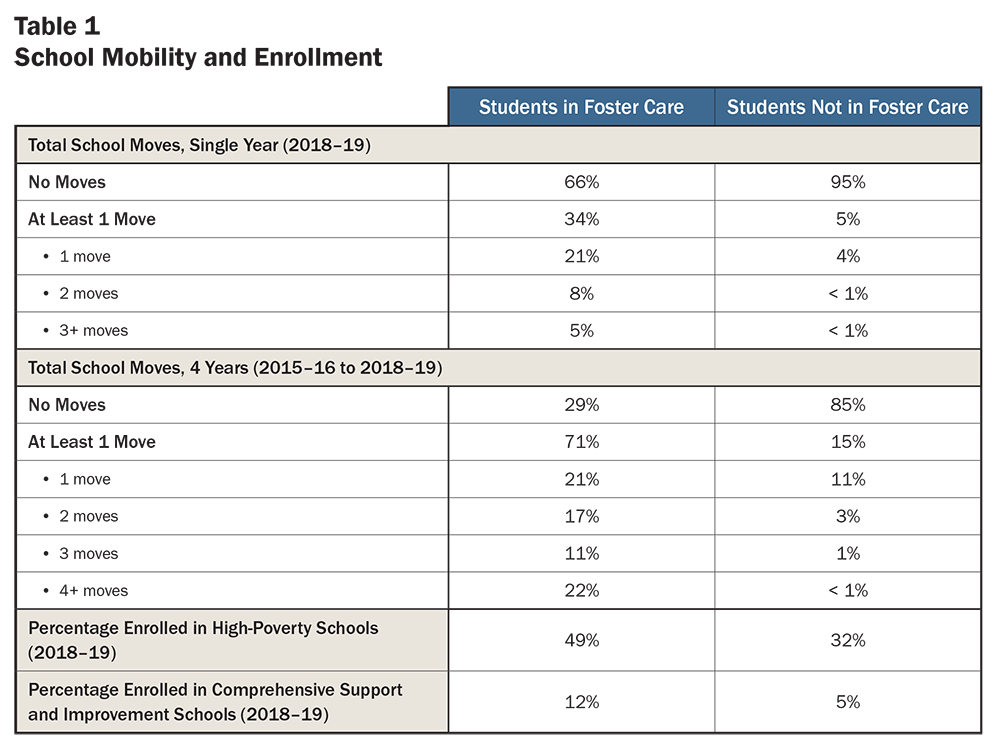

Students in foster care were more likely to move schools within the academic year than other students, and many moved multiple times. While only 5% of non-foster students moved schools during the 2018–19 school year, 34% of students in foster care did so. Over 4 school years, almost three quarters of students in foster care moved schools at least once, and almost one quarter moved schools four or more times. (See Table 1.)

Data sources: Data provided by the California Department of Education through a special request; Public School and District data files and Free or Reduced-Price Meal data files downloaded from https://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/ad/downloadabledata.asp; Every Student Succeeds Act Assistance Status Data Files downloaded from https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/sw/t1/essaassistdatafiles.asp

Absenteeism and Suspension Rates

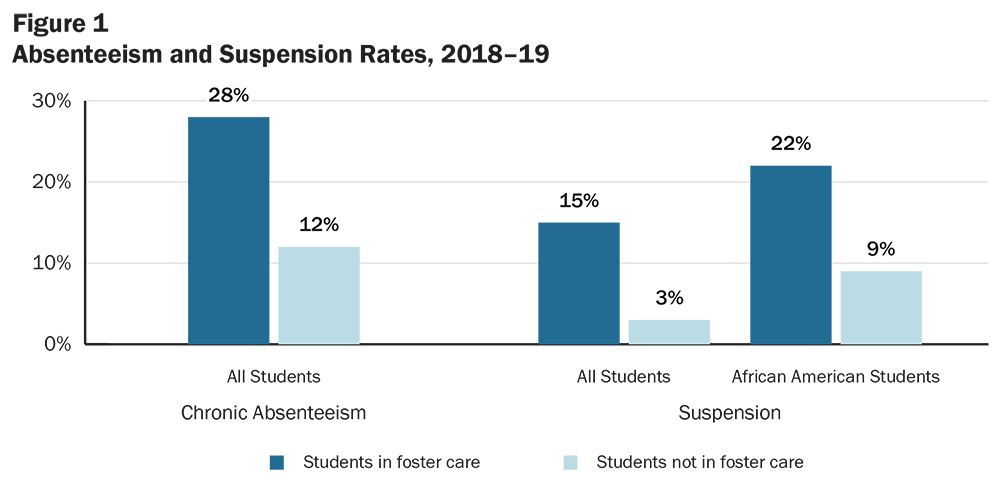

Students in foster care were twice as likely to be chronically absent as students not in foster care (see Figure 1), missing an average of 15 days in the 2018–19 school year. Moreover, absenteeism was especially high among high school students in foster care, who were absent an average of 23 days, or 1 out of every 8 school days.

Students in foster care were also more likely than their peers to miss school due to exclusionary discipline. At 15%, the suspension rate for students in foster care was more than 4 times that for non-foster students. Suspension rates were especially high among African American students in foster care.

School Conditions

Nearly half of all students in foster care were enrolled in the highest-poverty schools, those in which more than 80% of students are eligible for free or reduced-price meals. High-poverty schools tend to experience greater resourcing challenges, including higher teacher turnover, that can negatively affect student outcomes.Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). The trouble with teacher turnover: How teacher attrition affects students and schools. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27, 36; Chen, T., & Hahnel, C. (2017). The steep road to resource equity in California education: The Local Control Funding Formula after three years. Education Trust–West. Furthermore, students in foster care were more likely than their peers to be enrolled in the lowest-performing schools, according to the state’s accountability system.

Academic Outcomes of Students in Foster Care

We explored how the educational experiences of students in foster care were associated with academic outcomes. We also analyzed the California Department of Education data to examine the academic achievement and graduation and college-going rates of students in foster care.

Academic Achievement

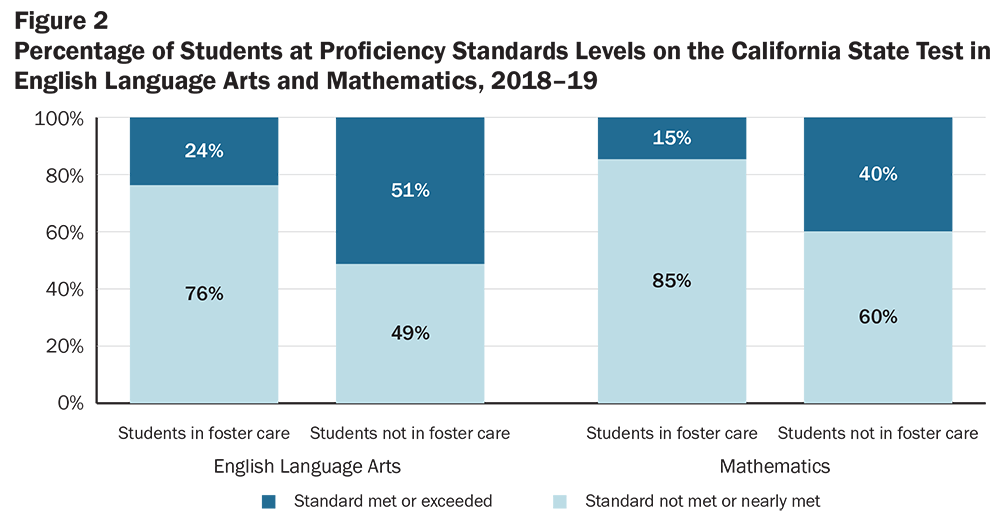

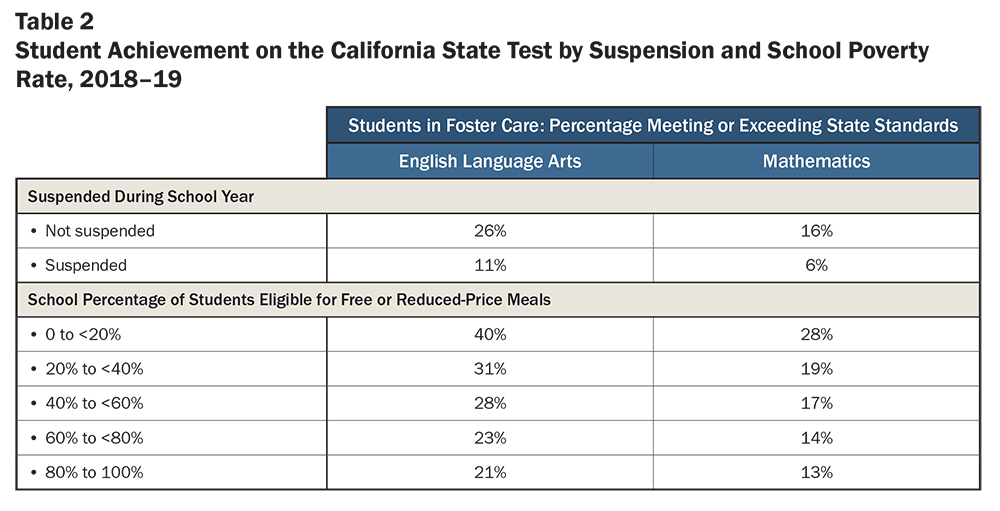

On state tests, students in foster care were less than half as likely as other students to meet the proficiency standard in English language arts (24% vs. 51%), and even less likely to meet proficiency standards in mathematics (15% vs. 40%). (See Figure 2.) These gaps were more pronounced for students in foster care who were highly mobile, who experienced suspension, who were in multiple high-need groups (e.g., English learners in foster care), or who were attending high-poverty schools.

Data source: Data provided by the California Department of Education through a special request.

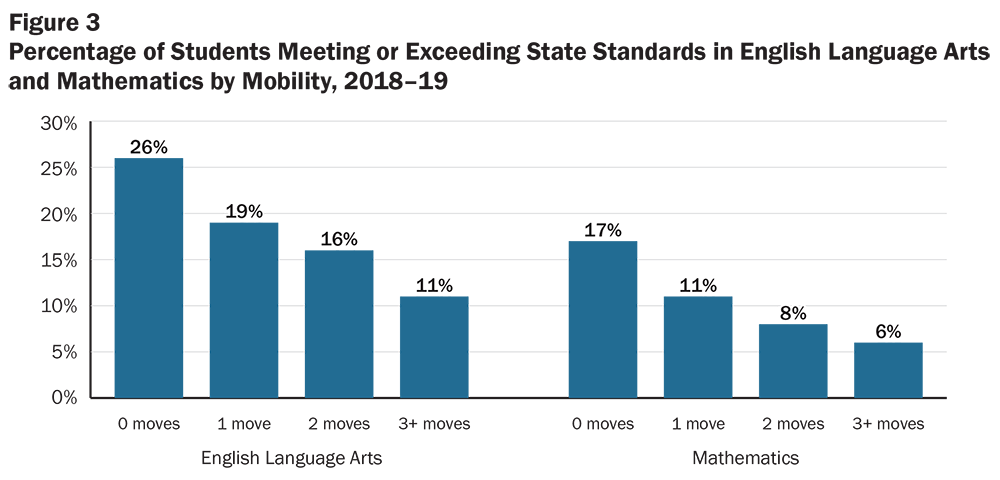

In particular, high mobility was associated with lower state test scores. Among students in foster care who stayed in the same school throughout the school year, about one quarter met or exceeded state standards in English language arts, and almost one fifth did so in mathematics. However, each school move was associated with lower scores in both subjects. For example, students in foster care who moved three or more times met or exceeded the state standards at less than half the rate of students in foster care who did not change schools.

Data source: Data provided by the California Department of Education through a special request.

Students in foster care who were suspended also lost more ground academically, reaching state proficiency standards at less than half the rate of foster care students who were not suspended and at less than one quarter the rate of students not in foster care. (See Table 2.) While all students who received suspensions achieved these standards less frequently, this is particularly relevant for students in foster care, who are suspended at higher rates. In addition, the percentage of students in foster care in the lowest-poverty schools meeting or exceeding state standards was around twice that of those in the highest-poverty schools.

Graduation and College-Going Rates

Students in foster care graduated at lower rates than youth not in foster care (56% vs. 85%). While the graduation rate for students in foster care is low relative to their peers, it increased 5 percentage points between 2016–17 and 2018–19 (from 51% to 56%). Among graduates and other high school completers, students in foster care were also less likely than their peers to attend college (48% vs. 64%).

Challenges to Supporting Students in Foster Care

To better understand how districts bring together and manage supports for students in foster care, we interviewed 11 Foster Youth Services Coordinating Programs (FYSCP) coordinators who act as a bridge between education and child welfare agencies. They identified challenges with data systems, funding, transportation, and capacity, along with underlying barriers to interagency collaboration.

Data Systems

Coordinators identified two major areas in which data systems are often insufficient: (1) individual student case management and (2) aggregate data analysis.

Effective case management relies on the availability of timely student-level data, including student attendance, grades, assessments, and progress toward educational goals. Frequently, however, gaps in data systems result in poor data quality and impact educators’ abilities to effectively share and receive data on students in foster care. Consequently, some county education staff need to use multiple data systems to accomplish a single objective.

Current systems are also inadequate for analyzing trends in aggregate data to see broader trends. School mobility data is one area for improvement. For example, county data systems may not capture the reason behind a school move (e.g., whether it was occasioned by a change in foster care placement), only that a school change happened. Coordinators, districts, and counties need data systems that enable better assessment of the impact of conditions such as school moves for individual students and broader efforts to support school stability.

Funding

The Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), California’s formula for allocating state funds to local districts, raises the visibility of students in foster care but may not provide sufficient resources to meet their multiple needs. California uses “unduplicated” counts of students to allocate supplemental funding. This means the formula provides additional funding for a student who falls into any of the high-need categories—students eligible for free or reduced-price meals, English learners, and students in foster care—but does not add further funding for students who fall into multiple categories. Since all students in foster care are automatically eligible for free school meals, they do not yield additional funds beyond those allocated for students from low-income backgrounds, despite their greater needs. Also, districts may provide blanket supports for all high-need student groups without adequate consideration of the unique needs for students in different groups.

Transportation

Students in foster care have a right to stay in their schools of origin, and the data show that they have better school outcomes when they are able to do so. However, when students are placed in out-of-home foster care beyond the attendance area of their schools of origin, the time and costs of transportation can make continued attendance at those schools challenging. Rural counties or small school districts, in particular, may have less flexibility to reroute buses. Partnering with private transportation offers useful flexibility in some counties but can be prohibitively expensive. Finally, transportation reimbursement rates for caregivers need to be regularly updated so as not to act as a barrier to transportation.

Interagency and interdistrict transportation agreements for transporting students in foster care to school, as required under federal law, are a related challenge. Differing levels of urgency, incomplete data about transportation needs, and fears of high costs can complicate establishing memorandums of understanding. The result may be that these take years to develop and implement.

Capacity

Given the interconnectedness of education and child welfare agencies in supporting students in foster care, challenges in one agency or at one level of the system can also create obstacles in others. For this study, we spoke only to representatives from education agencies, but these interviews identified some constraints for their colleagues in the child welfare system that directly impact school stability. For example, high caseloads for social workers can constrain collaboration across agencies, making it difficult to prioritize education in placement decisions, limit available time for best interest determinations,Under federal law, it is assumed that students will remain at their schools of origin unless a school transfer is determined to be in their best interest. The best interest determination is the process by which this decision is made. See Every Student Succeeds Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1003A (g)(1)(E)(i) (2015). (accessed 09/29/21). and contribute to students changing schools. Additionally, a shortage of skilled caregivers and services for children with the most acute needs may lead to more placement instability. When there is a lack of placements that can provide adequate and appropriate support, children are more likely to be moved far distances to receive care, which frequently requires a school move.

There will always be a need to make quick decisions to protect some children in the foster care system, so ensuring both the child welfare and education systems are designed to be responsive to such moments can have a major impact on the lives and educational outcomes of students in foster care. Without deep collaboration across agencies, education agencies will be left reacting to placement changes rather than planning for them, and students will experience disruptive changes.

Existing Policies and Promising Practices

Many of the challenges outlined in the previous section demand coordinated policy efforts to meet the needs of students in foster care. Over the past couple of decades, policy developments at both the state and federal levels have helped elevate and support districts in meeting the needs of youth in foster care:

- Assembly Bill (A.B.) 490, passed in 2003, created a series of educational rights for students in foster care in California, including the entitlement to remain in their schools of origin following a placement change, the right to immediate enrollment, and credit and grade protections connected to absences caused by placement changes.A.B. 490. (2003). (accessed 03/10/22). For additional information, see the National Center for Youth Law summary Happy birthday Assembly Bill 490: Celebrating 10 years of improving educational stability for students in foster care. (accessed 03/10/22).

- In 2015, the state passed A.B. 854, establishing the FYSCP and requiring data sharing between the Departments of Education and Social Services.

- The same year saw the Continuum of Care Reform (A.B. 403), which sought to provide more appropriate child welfare services and supports in home-based settings and to reduce time spent in congregate care, a placement setting linked to higher dropout rates for youth in foster care.A.B. 403. (2015). (accessed 03/10/22); California Department of Social Services. (n.d.). Continuum of care reform. (accessed 07/29/21).

- In 2018, A.B. 2083 built on A.B. 403 by developing a coordinated, timely, and trauma-informed system-of-care approach for children in foster care who have experienced severe trauma.A.B. 2083, Trauma-informed system of care. (2018). (accessed 03/10/22). The law aimed to eliminate agency silos by creating an interagency leadership team.

Recent policy reforms reflect growing recognition among California decision-makers that children in foster care benefit from stable relationships and supportive services. However, effective implementation of policy reforms remains a work in progress. Against the backdrop of these existing policy efforts, FYSCP coordinators interviewed for this study identified the following research-aligned programs and processes that could continue to improve the landscape of supports for students in foster care.

Co-Location of Staff

Students in foster care sit at the intersection of multiple systems. The child welfare system is charged with student safety, and schools and districts are charged with student education.Family courts, community, and health organizations, and, depending on the circumstances, probation officers may also play important roles in the lives of students in foster care. Because much of the decision-making that impacts students in foster care happens at the county level, collaboration among county partners is particularly important for ensuring that these students receive access to a ready web of critical services and supports.

Co-locating education and child welfare staff can strengthen interagency coordination and communication, which, in turn, can improve individual student case management. Co-location typically involves FYSCP staff sharing office space with other county agencies, and vice versa, to ensure that staff responsible for serving students in foster care are located in close physical proximity to one another. Research finds that co-location can help overcome barriers to interagency collaboration through better understanding of partner agency policies and procedures and improved data sharing.Zetlin, A. G., Weinberg, L. A., & Shea, N. M. (2006). Seeing the whole picture: Views from diverse participants on barriers to educating foster youths. Children & Schools, 28(3), 165–173.

For example, a 2016 report on FosterEd’s Education Team model in Santa Cruz—in which education liaisons are co-located in county education and child welfare offices as part of a multiagency team—found improved attendance and grade point averages for students in foster care who received liaison support.Laird, J. (2016). FosterEd Santa Cruz County: Evaluation final report. RTI International.

One-Stop Resource Centers

Developing one-stop resource centers can help provide a ready web of supports. For example, Kern County’s Dream Center serves as a one-stop shop for youth in foster care, particularly those close to aging out of the system. The center is equipped to provide an array of services for these youth, from assistance accessing housing, health care, tutoring, and job training to offering laundry and shower facilities, emergency hygiene supplies, and medical services. Staff from the county office of education, the Department of Human Services Independent Living Program, child welfare social workers, housing coordinators, behavioral health staff, and probation officers work in close collaboration at the site. The Dream Center demonstrates how developing partnerships with county agencies, aligning goals, and coordinating community resources can benefit youth in foster care.

School-Level Relationships

School-level practices that promote trusting relationships with students in foster care are promising ways to improve the students’ educational opportunities. Research confirms that a student’s development is optimally supported when all aspects of the educational environment address major developmental needs (e.g., the need for strong relationships; social, emotional, and cognitive learning opportunities; and a system of supports to address individual circumstances).Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher. D. (2020) Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development, Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. Such “relationship-centered” schools emphasize the role of educative and restorative approaches to dealing with problematic behaviors, reducing the use of exclusionary discipline and lowering the risk of disengagement. As such, some districts have prioritized strong school–student relationships and employed school-based liaisons trained to support students in foster care. Liaisons get to know students deeply through frequent interactions, can assist with credit recovery, and can ensure students in foster care understand their rights.

Another strategy for fostering positive relationships is to create spaces in which students in foster care can elevate their needs and advocate for themselves, such as the Youth Empowering Success (YES!) clubs in Kern High School District. These on-campus groups of students in foster care serve as support groups and as forums for presentations from educators and other professionals on topics selected by the students.

Tiered Support Systems

Providing students in foster care with targeted social, emotional, and academic services as part of a tiered system of support can help address the range of challenges they face.Adelman, H., & Taylor, L. (2020). Embedding mental health as schools change. Center for Mental Health in Schools & Student/Learning Supports, University of California, Los Angeles; Moore, K. A., & Emig, C. (2014). Integrated student supports: A summary of the evidence base for policymakers. Child Trends; Pollack, C., Lawson, J. L., Raczek, A. E., Dearing, E., Walsh, M. E., & Kaufman, G. (2020). Long-term effects of integrated student support: An evaluation of an elementary school intervention on postsecondary enrollment and completion. Center for Optimized Student Support, Boston College; Somers, M., & Haider, Z. (2017). Using integrated student supports to keep kids in school: A quasi-experimental evaluation of Communities In Schools. MDRC. Supports can include mental health services, support for transitions, timely assessment for academic needs, screening for special education, support for school engagement, and an evaluation of credits for high school students. Access to such a web of supports can help address academic and nonacademic barriers to student learning as well as make up for lost instructional time due to absences, exclusionary discipline, and school mobility, which the quantitative data show is an urgent concern for students in foster care.

One model for delivering multi-tiered, integrated supports is through community schools. Community schools are both places and sets of partnerships between the education system, the nonprofit sector, and local government agencies. They are designed to bring together a comprehensive range of services and resources at the school site. By coordinating academic, mental health, physical wellness, social and emotional, and other supports, community schools contribute to a whole child approach to education that can benefit students in foster care, among others with a range of needs.

Policy Recommendations

While California’s foster care system is administered at the county level by child welfare agencies, county education agencies, districts, and school officials all play a role in responding to the educational needs of students in foster care. The quantitative and qualitative findings of this report point to the need for systems and practices that provide students in foster care with access to a ready web of supports so that they can receive help as soon as they need it.

We suggest the following policy recommendations to better serve the educational needs of students in foster care:

1. Implement organizational structures that support cross-system collaboration.

Collaborative interagency structures grounded in shared objectives and responsibility for students and families are needed to ensure that students in foster care receive supports quickly and efficiently.

- Create or empower cross-agency structures to improve collaboration and delivery of services. A formalized cross-agency team, such as a children’s cabinet, could improve state-level coordination and alignment. Such a body could be empowered to support the development of policies that remove barriers to interagency collaboration and break down silos from different categorical funding and service streams; it could also establish shared goals for California’s children and families and support effective implementation of existing laws and protections for students in foster care.

- Support strong implementation of community schools. Community schools are designed to provide students with a whole child education by coordinating partnerships between the education system, the nonprofit sector, and local government agencies and by promoting strong family and community engagement. Access to supports offered by community schools—such as interdisciplinary teams that coordinate outreach to families, counseling and mental health services, high-quality tutoring, and transportation—can be critical to students in foster care due to their often-wide-ranging needs. California’s $4.1 billion Community Schools Partnership Program will transform all high-poverty schools, where most students in foster care are concentrated, into community schools. The program will also fund several technical assistance centers to support community school implementation. It will be important for this technical assistance to develop an infrastructure to identify and disseminate best practices among grantees and to build on lessons learned from existing initiatives, including the FYSCP.

- Support the development of local interagency transportation agreements to decrease school mobility arising from changes in foster care placements. State technical assistance through the interagency System of Care Team, such as transportation memorandum of understanding templates and best practices for implementing them, could support the development of local transportation agreements to facilitate school stability. Another function of state technical assistance could be identifying barriers that might require additional state action, including the cost of transportation.

2. Explore revising the LCFF to provide additional funding for students in multiple high-need groups.

The state could explore revising the LCFF to provide additional funding in a way that better accounts for students in multiple high-need groups—students from low-income families, students in foster care, students experiencing homelessness, and English learners—by examining evidence-based weighting for different needs. Such a reform could more equitably fund districts to support the range of needs students face, benefiting all students needing access to a web of supports.

3. Identify and implement strategies to improve student case management.

Disseminating best practices from existing efforts to connect a fragmented data ecosystem—namely, the Child Welfare Services/Case Management System, the California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System, and district student information systems—and increasing opportunities for interagency collaboration are critical steps that the state and counties can pursue to operationalize a web of supports and improve outcomes for students in foster care.

- Establish a state grant program to support the development and statewide dissemination of best practices for data-informed, collaborative case management. Effective local data systems are critical both for individual student case management and for understanding trends in student achievement, stability, and access to services and supports. Existing case management systems can connect otherwise fragmented data, but these systems are not used everywhere in the state, and where they are used, they are often not used by both education and child welfare staff. Further, incomplete or missing data can hamper their usefulness. The state could help cultivate the development, implementation, and dissemination of best practices for data-informed, collaborative case management for students in foster care by establishing a program similar to California’s Homeless Innovative Programs Grant, which is intended to identify and scale up innovative practices for supporting students experiencing homelessness.

- Co-locate education and child welfare office staff. Counties could consider co-locating education liaisons in child welfare offices, which can facilitate rapid communication of changes in a student’s foster care placement as well as urgent education, health, and mental health needs. This strategy can help provide educationally relevant information to ensure educational needs are considered in decisions about foster care placements.

4. Implement school designs and practices that allow for prompt identification and stronger support of student needs.

To support ongoing recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, district and school leaders can use resources, such as the $13.5 billion for California districts in the American Rescue Plan Act, to implement school and district practices that allow for prompt identification and support of student needs. Creating relationship-centered, trauma-informed schools grounded in the science of learning and development will be important for improving outcomes for students in foster care.

- Implement relationship-centered school practices as part of a tiered intervention system. Districts could organize schools to focus on relationship-centered practices that ensure each student is connected to caring adults who can identify and secure supports when they are needed. Relationship-centered schools involve strategies such as advisories, “looping,” team teaching, and scheduling that increases time for teacher collaboration. When implemented as part of the foundational tier in a multi-tiered system of support, these practices can support students in foster care by buffering the stresses of school and home instability and by connecting them to personalized supports and interventions.

- Increase access to professional development that equips school staff to address the needs of students in foster care. School staff need access to professional development that equips them to respond to the academic, social, emotional, and behavioral needs of students in foster care. Training could help staff understand the educational rights of students in foster care and focus on strategies grounded in the science of learning and development, including trauma-informed practices, restorative practices, and social and emotional learning. To support this, districts can leverage the $1.5 billion in funding provided through the Educator Effectiveness Block Grant.

California’s Students in Foster Care: Challenges and Promising Practices (research brief) by Dion Burns, Daniel Espinoza, Julie Adams, and Naomi Ondrasek is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Research was supported by the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.