The California Way: The Golden State’s Quest to Build an Equitable and Excellent Education System

Summary

In 2013, California adopted a bold, new approach to equitable funding, a more holistic vision of student and school success, and community engagement in decision making. These changes define a new era in the state’s educational history, which has come to be known as the "California Way." New policies focus learning on 21st-century skills of critical thinking and problem solving, more positive supports for students, capacity building through aligned educator preparation standards and professional development, and a continuous improvement process based on data about student progress on multiple measures to inform local investments. Outcomes to date include improved achievement and graduation rates, reduced suspension rates, and increased school safety, but there is more work to do to solve financial challenges, strengthen early learning, solve teacher shortages, close gaps in opportunity and outcomes, and build educator capacity.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

California students, families, educators, and policymakers are at the center of one of the most ambitious, equity-focused education reforms in the country. In 2013, the state adopted its Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), which has shifted billions of dollars to districts serving high-need students and provided all districts with broad flexibility to develop—in partnership with parents, students, and staff—strategies and spending plans aligned to local priorities and needs.

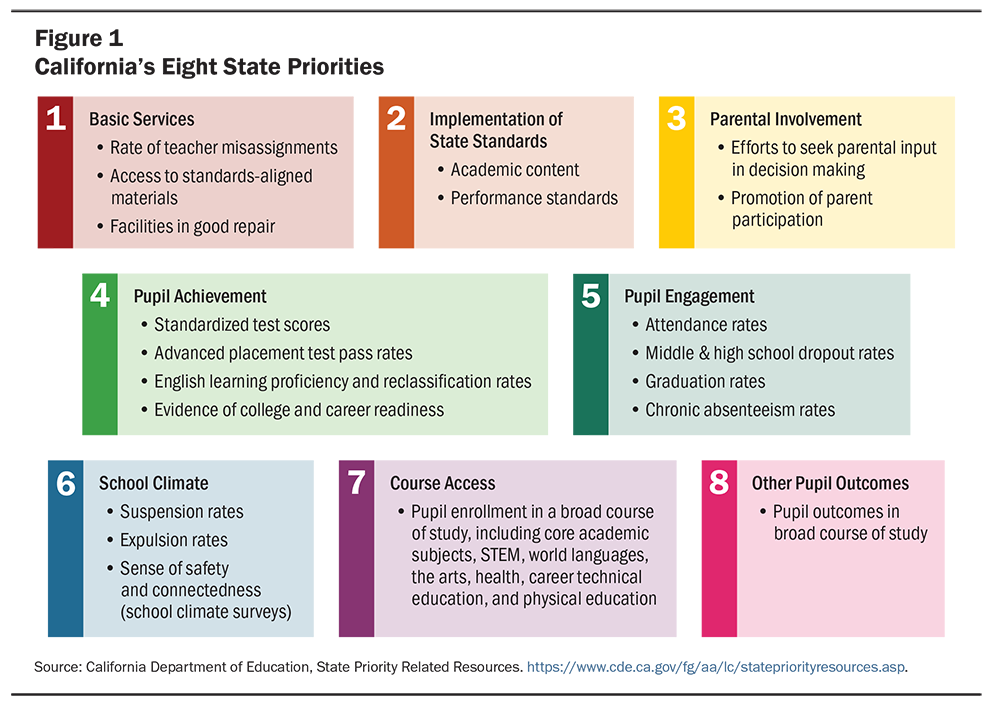

In place of the state’s previous test-based accountability system, LCFF established multiple measures of student and school success—eight priorities in all. (See Figure 1) These measures are used in every community to guide planning and budget decisions and to assess school progress and improvement efforts. Community engagement is central to the state’s new funding and accountability system. Districts are expected to work with all stakeholders—including families, students, and staff—to develop their Local Control and Accountability Plans (LCAPs) and evaluate progress annually. Counties evaluate district plans and support district improvement efforts.

The California Way

With this bold, new approach to equitable funding, a more holistic vision of student and school success, and community engagement in decision making, California defined a new era in its educational history, which has come to be known as the “California Way.” The California Way differs dramatically from the state’s prior approach and that initiated by the federal No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act. The “test and punish” philosophy—driving change in an inequitable system through sanctions for schools, educators, and students—has been replaced with one that seeks to “assess and improve” through data analysis and capacity building. The new approach also focuses on developing 21st-century skills of critical thinking and problem solving, building more positive supports for students, and replacing exclusionary discipline practices with restorative practices. Educator preparation standards have been updated to provide new teachers and principals with the skills needed to advance student learning in supportive and productive ways.

Instead of the “culture of compliance” that had permeated the public education system, the California Way reorients districts, counties, and the state to the principle and practice of “subsidiarity,” or local control. In partnership with students, families, and communities, school and district leaders are charged with assessing local needs, identifying priorities, making decisions collaboratively, and focusing on progress on a “whole child, whole school” agenda.

Although the scope and magnitude of the reforms have made many feel as if everything changed overnight, the changes were more than a decade in the making and reflect the contributions of a broad cross section of organizations and individuals: students and families from the state’s most marginalized and underserved communities and Sacramento advocates; teachers unions and district management; philanthropic and business leaders; researchers and state policymakers. Their individual and collective work paved the way for Governor Jerry Brown, a seasoned and popular governor, to flex his political and policy muscle to pass LCFF and a constellation of education reforms and for an aligned State Board and Department of Education to support the implementation of this new approach.

Local Control Funding Formula

Signed into law in July 2013, the LCFF redesigned California’s funding and accountability systems. In addition to creating an equity-focused funding formula, LCFF replaced the state’s test-based accountability system with one grounded in multiple measures of student and school success. Key elements include:

Funding based on student need: In addition to base grants, adjusted for various grade spans, LCFF includes supplemental grants of 20% of the adjusted base grant for each English learner, student in foster care, and student from a low-income family; and concentration grants of an additional 50% for these same student groups above 55% of enrollment.

Local decision making with significantly fewer spending requirements: With LCFF, California removed many spending restrictions that were part of the previous school funding system. Districts must use LCFF supplemental and concentration funds to “increase or improve” services for targeted students “in proportion to the increase in supplemental and concentration funds.”

Expanded local and state priorities: Integral to LCFF is an expanded view of student and school success, specifying eight state priority areas. Local districts are required to address each priority area in their LCAP, overall and for each major student group.

Stakeholder engagement in developing local plans and budgets: LCFF requires that districts engage parents, students, and other stakeholders in the development of LCAPs, which are adopted every 3 years, with annual updates and corresponding requirements for public hearings.

A Statewide System of Support, with a focus on continuous improvement: LCFF established a new accountability system based on a continuous improvement model that includes three levels of support for local education agencies. A new agency, the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence, together with county offices of education and the California Department of Education, comprise the state’s system of support.

Source: Taylor, M. (2013). Updated: An overview of the Local Control Funding Formula. Sacramento, CA: Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Taking Stock

As California transitions to a new governor and state superintendent of public instruction, it is a useful time to take stock of what has been accomplished and the challenges still to be addressed. This analysis is based on a review of research about the implementation and outcomes of the reforms and on interviews with actors and stakeholders.

Equitable Funding and Practices

The heart of LCFF is a simpler funding system that more equitably distributes the state’s k–12 resources among districts. As more resources have flowed to districts based on the needs of their students, researchers have documented important shifts in districts’ priorities, budgeting practices, and spending decisions, with increased attention to the unique needs of historically disadvantaged students. Statewide, districts are experimenting with strategies to address structural inequities, including sending money to school sites based on student need.

Creating a Student Equity Need Index

In the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), Community Coalition and InnerCity Struggle—two longtime community organizations that work with youth and adults of color in South and East Los Angeles, respectively—have partnered with the Advancement Project California to develop a Student Equity Need Index (SENI)Advancement Project. (n.d.). Student Equity Need Index. to inform how funds are distributed among district schools. The index, adopted in its current form in 2018, builds on the LCFF definition of need by including academic, in-school, and out-of-school—or community need—indicators, such as a school’s percentage of homeless students, suspension and chronic absenteeism rates, and English language arts (ELA) and math assessment scores, as well as neighborhood asthma severity rates and incidents of nonfatal gunshot injuries. The goal, say the groups, is “to make sure that communities and schools that [have] the highest need in the district [get] their equitable share of the money.”Interview with Henry Perez, Associate Director, InnerCity Struggle (2018, April 18).

Researchers have also documented increased collaboration between district finance staff and their colleagues in the program and education services departments. Rather than district finance staff informing their counterparts on the program side of how categorical funds could be used, district goals and strategies are now more likely to drive resource allocation decisions.

Still, information about within-district spending equity is not readily available. K–12 spending is also well below the national average when costs of education are taken into account; financial pressures include the rising costs of employee pensions and special education, and long-overdue facilities repairs and maintenance, all of which are consuming a greater percentage of district budgets.Krausen, K., & Willis, J. (2018). Silent recession: Why California school districts are underwater despite increases in funding. San Francisco, CA: WestEd.

Pursuing Deeper Learning

Nearly 6 years into California’s reforms, reports suggest that many California districts are allocating increased funds to professional development around Common Core and instructional strategies for all students and, in some cases, for LCFF target groups. They are also investing in structures to promote increased collaboration and job-embedded supports, such as coaches, for teachers.

Teacher-Led Professional Development

The Instructional Leadership Corps (ILC) aims to support the successful implementation of Common Core and the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS) through a “teachers teaching teachers” approach to professional learning. More than 200 accomplished teachers, many of them National Board certified, plus a smaller number of administrators, have been trained as instructional leaders by the ILC. Regional and statewide convenings gather these leaders to learn from and with experts and scholars about standards-aligned instructional strategies and approaches to professional development. ILC participants then design and lead their own professional development to support instructional improvement.

To extend and sustain local capacity, the ILC also helps teacher leaders develop partnerships with school districts, county offices of education, institutes of higher education, and their local teacher associations. To date, the ILC has served more than 100,000 teachers from more than 2,000 schools in 495 districts across the state, building local district capacity in the process.

Education leaders are also leveraging professional learning networks, or cross-district learning opportunities, that enable the systematic sharing of expertise to build capacity within and across districts, such as the NGSS Early Implementers Initiative and the Math in Common Community of Practice.

While research suggests that promising instructional and curricular shifts are taking hold, reports also shed light on ongoing areas for improvement, including more focused professional learning and instructional supports for underserved subgroups. Local leaders also face a significant challenge in strengthening teaching and learning due to persistent teacher shortages and high turnover of superintendents, principals, and teachersDarling-Hammond, L., Sutcher, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Teacher shortages in California: Status, sources, and potential solutions. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.—especially in schools serving high concentrations of students of color and students from low-income families.

School Climate

LCFF builds on earlier local- and state-level efforts to curtail exclusionary discipline practices and foster safe, inclusive school communities. By elevating school climate as one of the eight state priorities and tracking suspensions—overall and by student subgroup—on the California School Dashboard, LCFF has catalyzed increased attention to improving school climate.

Some districts are attending to school climate by increasing their students’ access to staff (such as counselors, social workers, and psychologists) who can address their holistic needs.Roza, M., Coughlin, T., & Anderson, L. (2017). Taking stock of California’s weighted student funding overhaul: What have districts done with their spending flexibility? Washington, DC: Edunomics Lab at Georgetown University. Student surveys, used to measure school climate under LCFF, inform local changes by allowing young people to share their sense of safety and connectedness, making California one of a small subset of states to use this tool.Kostyo, S., Cardichon, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2018). Making ESSA’s equity promise real: State strategies to close the opportunity gap. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Becoming a "Restorative Justice District"

In the summer of 2014, the San Diego Unified School District (SDUSD) embarked on a multipart strategy to become a restorative justice district. It eliminated its zero-tolerance discipline policy and then piloted restorative justice approaches in select high schools before expanding the effort districtwide. It also established a restorative justice department to support professional development. These changes were supported by $52 million in LCFF funds, according to the 2017–18 LCAP, along with other grants.

San Diego is one of the state’s positive outlier districts in which students of color as well as White students have outperformed predicted outcomes on the new math and ELA tests. The district has shown extraordinary success in educating African American and Latino/a students.Hernández, L., & Podolsky, A. (2019). San Diego Unified School District: Raising the bar on equity and rigor to support student achievement. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. (Forthcoming)

California districts are increasingly investing in evidence-based approaches to improve school climate and conditions, including social and emotional learning, Positive Behavioral Interventions and Support (PBIS), and restorative justice practices. By 2017–18, 92% of the state’s 50 largest districts reported investments in one or more of these programs.Lee, B. (2018). Using the California School Dashboard and LCAP to improve school climate: An analysis of 2017–18 LCAPs for California’s 50 largest school districts. Washington, DC: Council for a Strong America. While highlighting this progress, researchers also noted, however, that greater and ongoing investments in these programs are necessary to ensure effective implementation.

Despite the promising efforts, persistent teacher shortages undermine progress, as does the need for ongoing professional development. A recent survey of California principals found that fewer than one third felt “well” or “very well” prepared to lead schools that address the needs of the whole child, and more than 90% wanted more professional development on how to support social-emotional learning and positive school climate.Sutcher, L., Podolsky, A., Kini, T., & Shields, P. (2018). Learning to lead: Understanding California’s learning system for school and district leaders. Stanford, CA: PACE (accessed 11/16/18). Another challenge is the inconsistent administration and use of climate surveys and lack of support for helping staff interpret and use these data.

Engagement

Embedded in LCFF are groundbreaking engagement requirements designed to help realize the law’s vision of local control. Every year, district leaders are required to convene and solicit input from students, parents, staff, and the broader community on their LCAPs. Organized parents and students, in particular, have leveraged this opportunity to increase investments in school climate, family engagement, restorative justice, and additional supports for high-need students and schools. The engagement requirements have also sparked new and expanded district efforts to bring students and families into the local budgeting and planning process.

Despite these efforts, many districts struggle to engage families in meaningful ways, particularly those from marginalized communities. It will take time and a focused capacity-building effort to match district practices with the aspiration of deep engagement. It may also take strategies to improve the lengthy, complex LCAP documents so they can be understood by community members.

Tapping Into Community Expertise

The Alameda County Office of Education is partnering with school district leaders and community-based organizations to support and build the capacity of staff from local districts to engage diverse families. The county, which runs a professional learning network (PLN) for eight districts in Alameda County, has organized opportunities for parents, students, and organizers to share their experiences of local engagement efforts and to offer alternative strategies. PLN members and leadership from all 18 county districts have participated in these sessions.

In addition to its focused work on capacity building, the county is working with district staff to shift from the “shaming and blaming” that often happens to families who are not involved in school or district activities to “unpacking the reasons why certain families aren’t able to engage,” explained Jason Arenas, Director of Accountability Partnerships.

Assessing Impact

These changes in funding, accountability, standards, curriculum, and teaching raise an obvious question: How are educational outcomes changing in California? Although it is impossible to link outcome changes directly to specific policy decisions, since large-scale changes are determined by multiple factors, the general trends suggest both progress and areas of need.

Academic Achievement

In 2007, California’s 8th-grade students ranked 45th in mathematics on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), 49th in reading, and 49th in science. By 2017, California had experienced among the largest increases of any state. California 8th graders had nearly reached the national average in reading (just 2 points shy) and had cut their distance to the national average in half in mathematics (just 5 points shy). There is still room for improvement, however, in reaching the levels of performance in other states and closing the still-large gaps in performance between students of color and White students.The Nation’s Report Card. (n.d.). Data tools: State profiles. California overview (accessed 08/30/18).

A study from Getting Down to Facts II found that the gaps between California districts and others of similar socioeconomic status (SES) nationally are present at kindergarten entry and narrow slightly by the time students reach 8th grade. This suggests that, controlling for SES, California schools are about as effective as others across the country in promoting learning once students get to school. At the same time, it points to the need for more attention to early childhood education.Reardon, S. F., Doss, C., Gagné, J., Gleit, R., Johnson, A., & Sosina, V. (2018). A portrait of educational outcomes in California. Stanford, CA: PACE.

Another study from Getting Down to Facts II, using rigorous causal methods to test the effects of the new funding scheme, found that “increases in per-pupil spending caused by LCFF led to significant increases in high school graduation rates and student achievement,” with particularly significant gains in mathematics for students from low-income families.Johnson, R. C., & Tanner, S. (2018). Money and freedom: The impact of California’s school finance reform. Stanford, CA: PACE.

Graduation rates have indeed increased substantially in California, from 75% of students graduating within 4 years in 2010 to 83% in 2018.California Department of Education. (2018, November 19). State Superintendent Torlakson announces 2018 rates for high school graduation, suspension and chronic absenteeism (accessed 01/22/19). All groups have improved substantially, although gaps remain for African American and Latino/a students.

Student Exclusions and School Climate

Suspension and expulsion rates declined between 2012 and 2017, beginning even before the statewide prohibition on use of “willful defiance” for expulsions across all grades and for suspensions in k–3.

A Getting Down to Facts II study found that California generally has lower rates of exclusionary discipline compared to the national average and has reduced its reliance on exclusionary discipline by more than one third since the 2011–12 school year. The researchers also found that these declines have held true for all racial and socioeconomic groups and school levels, narrowing disciplinary gaps among racial/ethnic groups across the state.Reardon, S. F., Doss, C., Gagné, J., Gleit, R., Johnson, A., & Sosina, V. (2018). A portrait of educational outcomes in California. Stanford, CA: PACE.

As school exclusions have decreased and more schools have incorporated social-emotional learning and restorative practices, federal data show that California schools have become safer.Musu-Gillette, L., Zhang, A., Wang, K., Zhang, J., Kemp, J., Diliberti, M., & Oudekerk, B. A. (2018). Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2017 (NCES 2018-036/NCJ 251413). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education, and Bureau of Justice Statistics, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. School-based firearm incidents in the state, which were well above the national average from 2009 to 2010, were far below the national average by 2015–16, declining by more than 50% in the 7-year period. Significant decreases also occurred in rates of school-based fights, bullying incidents, and classroom disruptions over that period.

At the same time, however, punitive discipline practices continue to impact students of color disproportionately and reductions appear to have plateaued in the last 2 years, suggesting that more work is necessary to ensure California schools are inclusive and responsive to all.Losen, D. J., & Martin, K. (2018). The unequal impact of suspension on the opportunity to learn in California: What the 2016–17 rates tell us about progress. Los Angeles, CA: Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles.

Looking Ahead

Nearly 6 years ago, California embarked on a massive overhaul of its education finance and accountability systems—seismic shifts that coincided with implementation of new content standards aligned to the Common Core. Taken together, these changes have impacted every level of the k–12 education system, requiring changes in both culture and practice at the classroom, school, district, county, and state levels.

While considerable progress has been made, there is much more work to do. Research suggests that major tasks remain in at least three areas:

1. Funding: Support LCFF fundamentals and strategic educational investments.

- Continue to refine current policies and deepen their implementation. The massive change in funding and accountability that occurred with LCFF, along with new standards and assessments, has taken root. While there is much work to be done, districts are beginning to make progress in this system. It is important to maintain stability so that schools and districts can continue to move forward. To the degree state policymakers express ongoing support and investment in the still-young LCFF system, while also engaging in midcourse corrections and refinements, local leaders will be inclined to do the hard work of investing in the practices and capacities needed to improve quality and advance equity.

-

Develop revenue streams and spending plans that will move the state toward adequacy, as well as equity, in funding. Despite significant increases in funding over the past 6 years, funding levels in California remain well below those of most other states.Imazeki, J., Bruno, P., Levin, J., Brodziak de los Reyes, I., & Atchison, D. (2018). Working toward K–12 funding adequacy: California’s current policies and funding levels. Stanford, CA: PACE. While LCFF has rationalized the finance system and has begun to stabilize most districts, researchers and practitioners agree that there is not enough money in the system to meet the needs of all students. Getting Down to Facts II researchers concluded that $25 billion per year above the 2016–17 spending levels would be required for all students to have the opportunity to meet the goals set by the state.Loeb, S., Edley, C., Jr., Imazeki, J., & Stipek, D. (2018). Getting down to facts II: Current conditions and paths forward for California Schools, Summary Report 2018. Stanford, CA: PACE.

One revenue initiative likely to appear on the November 2020 ballot would reassess commercial property taxes annually. If successful, the initiative would raise an estimated $11 billion a year, roughly 40% of which would go to k–12 education. A recent public poll shows support for this proposal.Polikoff, M. S., Hough, H. J., Marsh, J. A., & Plank, D. (2019). Californians and public education: Views from the 2019 PACE/USC Rossier Poll. Stanford, CA: PACE (accessed 02/04/19). Other revenue strategies will likely emerge.

In his first days in office, Governor Newsom announced plans, through his proposed budget, to provide $2 billion in additional funding for LCFF, $3 billion in relief for local districts and community colleges to offset the growing cost of employee pensions, and $576 million for special education.State of California Department of Finance. (2019, January 10). Governor’s budget summary, 2019–20: k thru 12 education. Getting Down to Facts II and other studies also suggest efforts are needed to devise new, more equitable approaches to funding facilities construction and maintenance and special education, as growing costs in both areas threaten the gains that have been made under LCFF.

-

Invest strategically in a well-functioning system of early childhood care and learning. As Getting Down to Facts II research demonstrated, k–12 students in California learn at comparable rates to children in demographically similar districts elsewhere in the country, but they come to school further behind and with yawning gaps in readiness. While the state’s new transitional kindergarten (TK) program benefits the 4- and 5-year-olds able to participate,Manship, K., Holod, A., Quick, H., Ogut, B., Brodziak de los Reyes, I., Anthony, J., Jacobson Chernoff, J., Hauser, A., Martin, A., Keuter, S., Vontsolos, E., Rein, E., & Anderson, E. (2017). The impact of Transitional Kindergarten on California students: Final report from the study of California’s Transitional Kindergarten program. San Mateo, CA: American Institutes for Research. the state’s non-system leaves most eligible young children unserved and offers highly variable quality.Melnick, H., Meloy, B., Gardner, M., Wechsler, M., & Maier, A. (2018). Building an early learning system that works: Next steps for California. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Governor Newsom has recognized the importance of early learning in his first proposed budget by calling for investments in full-day kindergarten and in facilities and professional development for educators in the early learning system. The state needs not only to invest more, but also to rationalize a complex set of currently uncoordinated programs around a master plan for access to high-quality early learning; adequate preparation for educators; and the blending, braiding, and streamlining of services that are currently inefficiently delivered.

- Refine and strengthen the accountability system. The State Board has done considerable work to refine and implement LCFF’s accountability framework, but there is ongoing work to be done to fine-tune the LCAP template so that it is accessible and useful to districts and stakeholders. In addition, there is work to do to finalize the state accountability system—finalizing indicators that are still under construction, clarifying which supports and actions will occur for districts and schools that are struggling and require intervention, and building a system of support that can truly help these schools and districts.

- Consider how the measurement of school climate and parent involvement can best inform educators and stakeholders and strengthen the ability of schools and districts to create safe, inclusive, and welcoming school environments by supporting their capacity to administer, analyze, and address concerns identified in school surveys.

- Address concerns about lack of transparency in local budgeting and planning processes. Clear, actionable information about district-level budgets, including planned and actual expenses, is foundational to the democratic decision making that undergirds LCFF. The recently developed Budget Overview for Parents may be a step toward this transparency.

2. Capacity building: Strengthen the capacity of districts, schools, and educators to address the state’s priority areas.

-

Build on existing assets to create a more comprehensive professional learning infrastructure. This is critical to ensure that every teacher and school leader has the learning opportunities needed to teach new standards effectively and create supportive classrooms. The statewide system of support not only should address the needs of struggling schools and districts after they have been identified for intervention, but also should create a set of supports enabling all schools to succeed in implementing the state’s priorities.

Rather than a top-down set of state mandates, the state could benefit from a strategy—like that developed by state education agencies in some other local control statesJaquith, A., Mindich, D., Chung Wei, R., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). Teacher professional learning in the United States: Case studies of state policies and strategies. Stanford, CA: Learning Forward and Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.—for taking stock of, coordinating, and seeding high-quality supports for educator learning. These supports, addressing the state’s priorities, may be provided through districts, county offices, universities, and nonprofit organizations in order to be readily available to educators across the state. There are significant assets in the state, such as the state Subject Matter projects, programs like Math in Common, and strategies like the Instructional Leadership Corps. However, they are not currently easily accessible, widely available, or coordinated in a strategic way.

Such a professional learning support system could guide the expansion of content-based supports that are proving successful. It could also guide supports for developing safe and inclusive classrooms; working with parents; and effectively teaching students with disabilities, English learners, students who have experienced trauma and adverse conditions, and others with exceptional learning and support needs.

- Develop and support networks for professional learning. The professional learning networks supported by the California Collaborative for Educational Excellence (CCEE), the Instructional Leadership Corps, and the collective work of the CORE Districts demonstrate the value of creating strong and supported networks to build the capacity of educators and district leaders to increase opportunity and advance student achievement. The success of these efforts offers important lessons for future efforts.

- Learn from exemplars. Throughout the state, schools and districts are leveraging new flexibility and increased resources to improve practice, experiences, and outcomes across the range of state priority areas. The California Department of Education (CDE) has engaged a working group to identify and elevate “Bright Spots” around the state. A critical role for both the CDE and CCEE, as part of the Statewide System of Support available to all schools and districts, will be to cast a broad net to identify exemplars and create a statewide infrastructure to support learning from these best practices and skilled practitioners and leaders.

- Build the capacity of teachers and school and district leaders to authentically engage families. Research underscores the link between family engagement and student progress. However, this remains an area in which educators and local policymakers often continue to struggle, particularly when it comes to engaging families of students who have historically been marginalized and underserved. The community engagement initiative funded in the state’s 2018–19 budget is a first step in building capacity. The Statewide System of Support should also help build district capacity in this critical area.

3. Staffing: Strengthen the educator workforce.

-

Build a strong, stable, and diverse teacher workforce. Persistent teacher shortages threaten to undermine efforts to improve educational opportunities and outcomes, particularly in schools serving large numbers of students from low-income families and students of color, where shortages are most prevalent.

Many strategies can be used to build a pipeline into the profession: Forgivable loans and scholarships, which underwrite preparation—and are repaid by service for several years in the classroom—are one way to recruit new teachers to shortage fields and locations. They enable people to choose teaching without incurring debilitating debt, as do high-retention pathways, such as teacher residency programs and Grow Your Own programs, which have received one-time funding from the state.

Each year, 6 out of 10 open teaching positions are created due to the departure of teachers who left the previous year for reasons other than retirement. This high attrition rate means that it is also important to focus on retention. Adequate mentoring for beginning teachers and ongoing learning supports are needed to increase retention, as are supportive principals—always cited by teachers as a key factor in their decisions about whether to stay at a given school.

- Invest in school and district leaders. Skilled school and district leaders are critical to building a strong and stable workforce—and to making the important shifts in culture and practice envisioned by LCFF and the Common Core State Standards. Yet fewer than one third of California principals reported in a recent survey that their preparation helped them learn how to recruit and retain teachers and other staff.Sutcher, L., Podolsky, A., Kini, T., & Shields, P. M. (2018). Learning to lead: Understanding California’s learning system for school and district leaders. Stanford, CA: PACE (accessed 11/16/18). Many states are tapping ESSA Title II funds to invest in leadership training. Some analysts have suggested a return of California’s School Leadership Academy, once so successful in preparing principals, central office staff, and teacher leaders for turnaround situations, as well as for leadership in general.

Conclusion

With the passage of the Local Control Funding Formula and related reforms, California entered a new era in its decades-long quest for equity and excellence. With substantial new investments, coupled with a laser-like focus on students with the greatest need, the state has made important strides in creating the framework needed to provide every student with an excellent education. Continued progress will depend on deepening these strategies and investments, as well as on a focused effort to build the capacity of everyone in the system—teachers, school and district leaders, county and state officials, and families and communities—to capitalize on the new resources, flexibility, continuous improvement commitments, and community-based decision making that are the cornerstones of the California Way.

The California Way: The Golden State’s Quest to Build an Equitable and Excellent Education System (research brief) by Roberta C. Furger, Laura E. Hernández, and Linda Darling-Hammond is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

We are grateful to The S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation for its funding of this brief. Funding for this area of LPI’s work is also provided by the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Ford Foundation.