Educating the Whole Child: Improving School Climate to Support Student Success

Summary

This brief reviews research demonstrating that student learning and development depend on affirming relationships operating within a positive school climate. It describes how such an environment can provide all children with a sense of safety and belonging by creating safe and culturally responsive classroom communities, connecting with families, teaching social-emotional skills, helping students learn to learn, and offering a multi-tiered system of supports.

Across the country, there is renewed interest in a whole child approach to learning—an approach that many felt was pushed aside during the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) era, with its intense focus on raising test scores to avoid punitive consequences for students, teachers, and schools. The result was too often a “drill and kill,” “test and punish,” “no excuses” environment in which many children experienced a narrow curriculum and a hostile climate that discouraged them and pushed many out of school.Sunderman, G. L., Kim, J. S., & Orfield, G. (2005). NCLB Meets School Realities: Lessons From the Field. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Indeed, a 2006 national study of 6th- to 12th-graders found that:

- only 29% felt their school provided a caring, encouraging environment;

- fewer than half reported they had developed social competencies such as empathy, decision making, and conflict resolution skills; and

- 30% of high school students engaged in multiple high-risk behaviors such as substance abuse, sex, violence, and attempted suicide.Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432.

Non-supportive school conditions undermine student motivation and learning, facilitate student disengagement from school, and contribute to school failure and high dropout rates, especially for students of color, who graduate at much lower rates than their White peers.

By contrast, research has found that a positive school climate improves academic achievement and reduces the negative effects of poverty on achievement, boosting grades, test scores, and student engagement.Berkowitz, R., Moore, H., Astor, R. A., & Benbenishty, R. (2016). A research synthesis of the associations between socioeconomic background, inequality, school climate, and academic achievement. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 425–469; Wang, M-T., & Degol, J. L. (2016). School climate: A review of the construct, measurement, and impact on student outcomes. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 315–352. Indeed, new knowledge about human learning and development demonstrates that a positive school environment is not a “frill” to be attended to after academics and discipline are taken care of. Instead, it is the primary pathway to effective learning.

Because children learn when they feel safe and supported, and their learning is impaired when they are fearful or traumatized, they need both supportive environments and well-developed abilities to manage stress. Therefore, it is important that schools provide a positive learning environment that allows students to learn social-emotional skills as well as academic content.

In this brief we examine how schools can use effective, research-based practices to create settings in which students’ healthy growth and development are central to the design of classrooms and the school as a whole. We describe key findings from the sciences of learning and development, the school practices that should derive from this science, and the policy strategies that can support these conditions on a wide scale.

Key Lessons From the Science of Learning and Development

In recent years, a great deal has been learned about how biology and environment interact to produce human learning and development. A summary of the research from neuroscience, developmental science, and the learning sciences points to the following foundational principles:

1. The brain and development are malleable. The brain grows and changes throughout life in response to experiences and relationships. The nature of these experiences and relationships matters greatly for development.

Optimal brain development is shaped by warm, consistent relationships; empathetic back-and-forth communications; and modeling of productive behaviors. The brain’s capacity develops most fully when children and youth feel emotionally and physically safe; when they feel connected, supported, engaged, and challenged; and when they have rich opportunities to learn, with materials and experiences that allow them to inquire into the world around them.

2. Variability in human development is the norm, not the exception. The pace and profile of each child’s development are unique.

Because each child’s experiences create a unique trajectory for growth, there are multiple pathways—and no one best pathway—to effective learning. Rather than assuming all children will respond to the same teaching approaches equally well, effective teachers personalize supports for different children, and effective schools avoid prescribing learning experiences around a mythical average. When schools try to fit all children to one pace and sequence, they miss the opportunity to reach each child, and they can cause children to adopt counterproductive views about themselves and their own learning potential, which undermines their progress.

3. Human relationships are the essential ingredient that catalyzes healthy development and learning.

Supportive, responsive relationships with caring adults are essential for healthy development and learning. Positive, stable relationships can buffer the potentially negative effects of even serious adversity. When adults have the awareness, empathy, and cultural competence to appreciate and understand children’s experiences, needs, and communication, they can promote the development of positive attitudes and behaviors and build confidence to support learning.

4. Adversity affects learning—and the way schools respond matters.

Each year in the United States, 46 million children are exposed to violence, crime, abuse, or psychological trauma, as well as homelessness and food insecurity. These adverse childhood experiences create toxic stress that affects attention, learning, and behavior. Poverty and racism, together and separately, make chronic stress and adversity more likely. In schools where students encounter punitive discipline rather than support for handling adversity, their stress is magnified. Schools can buffer the effects of stress by facilitating supportive adult-child relationships that extend over time; teaching social and emotional skills that help children handle adversity; and creating helpful routines for managing classrooms and checking in on student needs.

5. Learning is social, emotional, and academic.

Emotions and social relationships affect learning. Positive relationships, including trust in the teacher, and positive emotions, such as interest and excitement, open up the mind to learning. Negative emotions, such as fear of failure, anxiety, and self-doubt, reduce the capacity of the brain to process information and to learn. Learning is shaped both by intrapersonal awareness, including the ability to manage stress and direct energy in productive ways, and by interpersonal skills, including the ability to interact positively with others, resolve conflicts, and work in teams. These skills can be taught.

6. Children actively construct knowledge based on their experiences, relationships, and social contexts.

Students dynamically shape their own learning. Learners compare new information to what they already know in order to learn. This process works best when students engage in active, hands-on learning and when they can connect new knowledge to personally relevant topics and lived experiences. Effective teachers draw those connections, create engaging tasks, watch and guide children’s efforts, and offer constructive feedback with opportunities to practice and revise work. Teachers also provide opportunities for students to set goals and assess their own work and that of their peers so that they become increasingly self-aware, confident, and independent learners.

Implications of the Science of Learning and Development for Schools

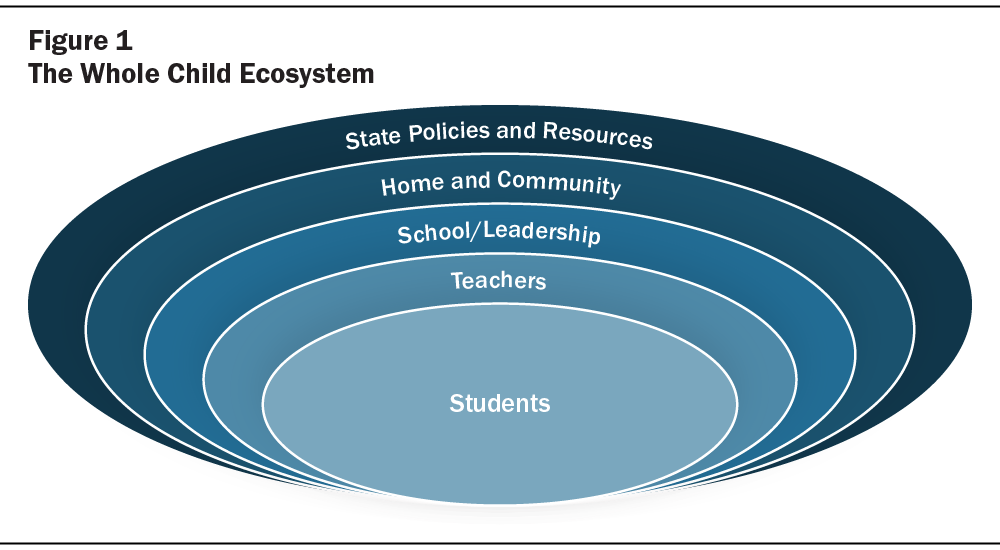

Given these insights, research suggests that schools should attend to four major domains, shown in Figure 1 and described below, to support student achievement, attainment, and behavior.

1. Supportive environmental conditions that create a positive school climate and foster strong relationships and community. These conditions can be accomplished through:

- a caring, culturally responsive learning community in which all students are valued and are free from social identity threats that undermine performance;

- structures that allow for continuity in relationships and consistency in practices; and

- relational trust and respect between and among staff, students, and families enabled by collegial supports for staff and proactive outreach to parents.

Personalizing the educational setting so that children can be well-known and supported is one of the most powerful levers to change the trajectories for children’s lives. Often, it is close adult-student relationships that enable students placed at risk to attach to school and gain the academic and other help they need to succeed.Friedlaender, D., Burns, D., Lewis-Charp, H., Cook-Harvey, C. M., Zheng, X., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2014). Student-centered schools: Closing the opportunity gap. Stanford, CA: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education; Lee, V. E., Bryk, A. S., & Smith, J. B. (1993). The organization of effective secondary schools. Review of Research in Education, 19, 171–267. But developing these relationships can be difficult in most U.S. secondary schools, where teachers see 150–200 students each day, students see seven to eight teachers daily, and the focus is on competitive ranking—just as young people most need to develop a strong sense of belonging and personal identity.Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2009). “Schools, Academic Motivation, and Stage-Environment Fit” in Lerner, R. M., & Steinberg, L. (Eds.). Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. Such depersonalized contexts are most damaging when students also experience the effects of poverty, trauma, and discrimination without supports that enable them to cope.

One way to create stronger relationships is by structuring small schools or small learning communities that feature structures such as advisory systems in which advisors work with a small group of students over multiple years, teaching teams that share students, or looping teachers with the same students over 2 years or more. Such approaches have been found to improve student achievement, attachment, attendance, attitudes toward school, behavior, motivation, and graduation rates.Bloom, H. S., & Unterman, R. (2014). Can small high schools of choice improve educational prospects for disadvantaged students? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 33(2), 290–319; Darling-Hammond, L., Ross, P., & Milliken, M. (2006). High school size, organization, and content: What matters for student success? Brookings Papers on Education Policy, 2006/2007 (9), 163–203; Felner, R. D., Seitsinger, A. M., Brand, S., Burns, A., & Bolton, N. (2007). Creating small learning communities: Lessons from the project on high-performing learning communities about “what works” in creating productive, developmentally enhancing, learning contexts. Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 209–221; Friedlaender, D., Burns, D., Lewis-Charp, H., Cook-Harvey, C. M., Zheng, X., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2014). Student-centered schools: Closing the opportunity gap. Stanford, CA: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. Teachers in personalized settings report a greater sense of efficacy, while parents report feeling more comfortable reaching out to the school for assistance.Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2009). “Schools, Academic Motivation, and Stage-Environment Fit” in Lerner, R. M., & Steinberg, L. (Eds.). Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; Felner, R. D., Seitsinger, A. M., Brand, S., Burns, A., Bolton, N. (2007). Creating small learning communities: Lessons from the project on high-performing learning communities about “what works” in creating productive, developmentally enhancing, learning contexts. Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 209–221.

Schools can also strengthen relational trust among educators and families, a key predictor of gains in achievement. As Bryk & Schneider put it: “Trust is the connective tissue that holds improving schools together.”Bryk, A., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. Schools can nurture trust by engaging parents as partners with valued expertise; building in time and support for teacher home visits and positive phone calls, texts, or email messages; and scheduling school meetings and conferences around parents’ availability.

Finally, schools can become “identity safe”—i.e., places where all students feel competent and supported in all classrooms. The way students are treated in school—or in society outside of school—can trigger or ameliorate social identity threat, which can affect members of groups that have been evaluated negatively in society—for example, on the basis of race, ethnicity, language, income, sexual identity, disability status, or gender. Because American schools exist within a societal climate that perceives—and misperceives—people in racial and ethnic terms, stereotype threat in the classroom is often powerfully experienced by students of color. This fear of being judged in terms of a group-based stereotype induces stress that impairs working memory and focus, leading to poorer performance on school tasks.Schmader, T., & Johns, M. (2003). Converging evidence that stereotype threat reduces working memory capacity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 440–452.

In addition, if students subject to social identity threat don’t know whether a school is safe and welcoming for them, many will assume it is unsafe and may become hypervigilant and defensive. When a student feels threatened, he or she may respond to a seemingly innocuous interaction with a disproportionately negative response.

To offset the discriminatory messages many students receive in the society at large, schools have an obligation to act affirmatively to make it clear to students that in this environment they will be safe, protected, and valued. This begins with positive cultural representations and messages of inclusiveness in the curriculum and classrooms. In addition, educators can mitigate stereotype threat by providing positive affirmations about each student’s value and competence—affirmations that studies show result in improved test scores, grades, and other academic measures.Steele, C. M. (2011). Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company. Teachers can also explain that assignments are meant to diagnose current skills that can be improved, rather than to measure ability. As they give constructive feedback about students’ work, they can note that the feedback reflects the teacher’s high standards and a conviction that the student can reach them, providing an opportunity to revise the work.Aronson, J. (2002). “Stereotype Threat: Contending and Coping With Unnerving Expectations” in Aronson, J. (Ed.). Improving Academic Achievement: Impact of Psychological Factors on Education (pp. 279–301). New York, NY: Academic Press. When teachers express this kind of confidence in students, they create an “identity-safe” atmosphere for learning to take place and for student achievement to improve continuously.

Identity-Safe Classrooms

Identity-safe classrooms promote student achievement and attachments to school.Steele, D. M., & Cohn-Vargas, B. (2013). Identity Safe Classrooms: Places to Belong and Learn. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. The elements of such classrooms, found to support strong academic performance for all students, include:

- Teaching that promotes understanding, student voice, student responsibility for and belonging to the classroom community, and cooperation in learning and classroom tasks.

- Cultivating diversity as a resource for teaching through regular use of culturally responsive materials, ideas, and teaching activities, along with high expectations for all students.

- Classroom relationships based on trusting, encouraging interactions between the teacher and each student, and the development of positive relationships among the students.

- Caring, orderly, purposeful classroom environments in which social skills are proactively taught and practiced to help students respect and care for one another in an emotionally and physically safe classroom, so each student feels respected by and attached to the others.

2. Social and emotional learning (SEL) that fosters skills, habits, and mindsets that enable academic progress and productive behavior. Such learning can be developed through:

- explicit instruction in social, emotional, and cognitive skills, such as intrapersonal awareness, interpersonal skills, conflict resolution, and good decision making;

- infusion of opportunities to learn and use social-emotional skills, habits, and mindsets throughout all aspects of the school’s work in and outside of the classroom; and

- educative and restorative approaches to classroom management and discipline, so that children learn responsibility for themselves and their community.

Many schools are using formal programs that teach social-emotional skills, such as Second Step, PATHS, and others. A meta-analysis of 213 studies of such programs found that, relative to other students, participating students showed greater improvement in their social and emotional skills; in attitudes about themselves, others, and school; in classroom behavior; and in test scores and school gradesDurlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432.—benefits that endured years later.Jones, D. J., Greenberg, M. T., & Crowley, D. M. (2015). Early social-emotional functioning and public health: The relationship between kindergarten social competence and future wellness. American Journal of Public Health, 105(11), 2283–2290; Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Development, 88(4), 1156–1171. Many schools also infuse social-emotional learning through the curriculum—for example, through curricula focused on perspective-taking and empathy in history and English language arts, and on community and social problem solving in social studies, mathematics, and science. Such efforts produce positive outcomes for student engagement, attachment to school, achievement, attainment, and behavior, including strong collaboration and support of peers, resilience, a growth mindset, and helpfulness toward others.Hamedani, M. G., Zheng, X., Darling-Hammond, L., Andree, A., & Quinn, B. (2015). Social emotional learning in high school: How three urban high schools engage, educate, and empower youth. Stanford, CA: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.

A positive approach to schoolwide discipline recognizes that students’ behaviors reveal skills that need to be taught and developed, rather than demanded through punishment. Explicit teaching of interpersonal skills, conflict resolution, and problem solving creates a virtuous circle of responsible behavior. Studies have found that even in elementary school, students who learn and practice conflict resolution skills become more inclined to work out problems among themselves before the problems escalate.Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R., Dudley, B., & Acikgoz, K. (1994). Effects of conflict resolution training on elementary school students. The Journal of Social Psychology, 134(6), 803–817. Students who have been aggressive benefit most in improved relationships, self-esteem, personal control, and academic performance.Deutsch, M. (1992). The effects of training in conflict resolution and cooperative learning in an alternative high school: Summary report. New York, NY: International Center for Cooperation and Conflict Resolution.

Restorative practices—which create systems for students to reflect on any mistakes, repair damage to the community, and get counseling when needed—reduce disciplinary referrals, suspensions, and expulsions and improve teacher-student relationships and academic achievement.Fronius, T., Persson, H., Guckenburg, S., Hurley, N., & Petrosino, A. (2016). Restorative Justice in U.S. Schools: A Research Review. San Francisco, CA: WestEd; Gregory, A., Clawson, K., Davis, A., & Gerewitz, J. (2016). The promise of restorative practices to transform teacher-student relationships and achieve equity in school discipline. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 26(4), 325–353. They support a sense of community and responsibility through strategies like daily classroom meetings, community-building circles, conflict resolution strategies, restorative conferences, and peer mediation.

By contrast, coercive discipline, in which schools manage student behavior largely through punishments, exacerbates discriminatory treatment of students,Townsend, B. (2000). The disproportionate discipline of African American learners: Reducing school suspensions and expulsion. Exceptional Children, 66, 381–392. as students of color are disproportionately removed from class and school compared to White students who exhibit the same behaviors. Exclusionary discipline does not teach new strategies students can use to solve problems, nor does it enable teachers to understand how they can reduce problem behavior.Losen, D. J. (2015). Closing the Discipline Gap. Columbia, NY: Teachers College Press. Further, the more time students spend out of the classroom, the more their sense of connection to the school wanes, both socially and academically. This distance promotes disengaged behaviors, such as truancy, chronic absenteeism, and antisocial behavior,Hemphill, S. A., Toumbourou, J. W., Herrenkohl, T. I., McMorris, B. J., & Catalano, R. F. (2006). The effect of school suspensions and arrests on subsequent adolescent antisocial behavior in Australia and the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39(5), 736–744. which in turn exacerbate a widening achievement gap and an increased likelihood of dropping out.Raffaele Mendez, L. M. (2003). “Predictors of Suspension and Negative School Outcomes: A Longitudinal Investigation” in Wal, J., & Losen, D. J. (Eds.). Deconstructing the School-to-Prison Pipeline (pp. 17–34). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

3. Productive instructional strategies that support motivation, competence, self-efficacy, and self-directed learning. These curriculum, teaching, and assessment strategies feature:

- meaningful work that connects to students’ prior knowledge and experiences and actively engages them in rich, engaging, motivating tasks;

- inquiry as a major learning strategy, thoughtfully interwoven with explicit instruction and well-scaffolded opportunities to practice and apply learning;

- well-designed collaborative learning opportunities that encourage students to question, explain, and elaborate their thoughts and co-construct solutions;

- a mastery approach to learning supported by performance assessments with opportunities to receive helpful feedback, develop and exhibit competence, and revise work to improve; and

- opportunities to develop metacognitive skills through planning and management of complex tasks, self- and peer assessment, and reflection on learning.

A key insight from the science of development is that learning is a function both of teaching and students’ perceptions about themselves as learners. Students will work harder to achieve understanding and will make greater progress when they believe they can succeed. A growth mindset—the belief that effort will lead to increased competence—is essential to motivation and learning.Dweck, C. S. (2000). Self-Theories: Their Role in Motivation, Personality, and Development. London, UK: Psychology Press. The core principle that skills can always be developed is consistent with evidence that the brain is constantly growing and changing in response to experience. Providing constructive feedback and opportunities for practice and revision are practices that enable learners to grow.Hattie, J., & Gan, M. (2011). “Instruction Based on Feedback” in Mayer, R. E., & Alexander, P. A. (Eds.). Handbook of Research on Learning and Instruction (pp. 249–271). New York, NY: Routledge.

The learning environment supports motivation when learning and mastery goals are emphasized, rather than grades or performance goals, and when teachers provide support, recognize effort and improvement, treat mistakes as learning opportunities, give students opportunities to revise their work, emphasize learning when evaluating, minimize individual competition and comparison, and group students by topic, interest, or choice.Blumenfeld, P. C., Soloway, E., Marx, R. W., Krajcik, J. S., Guzdial, M., & Palincsar, A. (1991). Motivating project-based learning: Sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26(3–4), 369–398. In addition, insights from the learning sciences reveal that humans are motivated by interactions and develop neural pathways when they produce and receive language in conversation,Kuhl, P. (2000). A new view of language acquisition. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. which means that intellectually stimulating classrooms should actively support discussion, debate, and collaboration.

Today’s expectations that graduates have the problem solving and interpersonal skills needed for 21st century success require a focus on instruction designed to foster outcomes such as higher order thinking, collaborative problem solving, and the development of a growth mindset. These abilities cannot be developed through passive, rote-oriented learning aimed at memorizing disconnected facts. They require deeper understanding that supports the use of knowledge in new situations.Goldman, S., & Pellegrino, J. (2015). Research on learning and instruction: Implications for curriculum, instruction, and assessment. Policy Insights From the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2(1), 33–41. Specific pedagogical moves that support deeper learning and motivation include:

- choice of tasks that have the right amount of challenge, demanding analysis to answer a question or develop a product, with supportive guidance and feedback;

- well-designed questions to stimulate inquiry and engagement, as well as to support students putting information together to find answers and consolidate understanding;

- varied representations of concepts that allow students to “hook into” understanding in different ways;

- design of instructional conversations and collaborative work that allows students to discuss their emerging thinking and hear other ideas, developing concepts, language, and further questions in the process;

- encouragement for students to elaborate, question, and self-explain; and

- apprentice-style relationships in which knowledgeable practitioners or peers facilitate students’ ever-deeper participation in a particular field.Bransford, J. D., & Donovan, M. S. (2005). How Students Learn: History, Mathematics, and Science in the Classroom (pp. 397–420). Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Finally, assessment plays a strong role in student motivation and learning. Research has found that a mastery-focused approach to assessment that emphasizes learning goals helps learners sustain effort and focus on improving competence and deeply understanding the work they produce.Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261. In addition, assessments that place value on growth rather than on scores create higher motivation and higher levels of cognitive engagement.Blumenfeld, P. C., Puro, P., & Mergendoller, J. (1992). “Translating Motivation Into Thoughtfulness” in Marshall, H. H. (Ed.). Redefining Student Learning, (pp. 207–241). New York, NY: Ablex Publishing Corporation. In contrast, researchers have found that evaluative, comparison-oriented testing focused on judgments about students leads to most students’ decreased interest in school, distancing from the learning environment, and a lowered sense of self-confidence and personal efficacy.Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2009). “Schools, Academic Motivation, and Stage-Environment Fit” in Lerner, R. M., & Steinberg, L. (Eds.). Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

In many learning-centered schools, projects, papers, portfolios, and other products are evaluated through rubrics that vividly describe dimensions of quality. When these are coupled with opportunities for feedback and revision, the assessments promote learning and mastery, rather than seeking to rank students against each other. These performance assessments encourage higher order thinking, evaluation, synthesis, and deductive and inductive reasoning while requiring students to demonstrate understanding.Darling-Hammond, L., & Adamson, F. (2014). Beyond the Bubble Test: How Performance Assessments Support 21st Century Learning. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons. The assessments themselves are learning tools that build students’ executive functioning, including their ability to plan and organize, as well as their growth mindset and ability to persevere in the face of challenges.

4. Individualized supports that enable healthy development, respond to student needs, and address learning barriers. These include:

- access to integrated services that enable children’s healthy development;

- extended learning opportunities that nurture positive relationships, support enrichment and mastery learning, and close achievement gaps; and

- multi-tiered systems of academic, health, and social supports to address learning barriers both in and out of the classroom.

Effective school environments take a systematic approach to promoting children’s development in all facets of the school and its connections to the community. Stress is a normal part of healthy development, but excessive stress in any of these contexts—at home, at school, or in other aspects of the community—can undermine learning and development and have profound effects on children’s well-being. Well-designed supports, including specific programs and interventions that buffer children against excessive stress, can enable resilience and success even for children who have faced serious adversity and trauma.

A key aspect of creating a supportive environment is a shared developmental framework among all of the adults in the school, coupled with procedures for ensuring that students receive additional help for social, emotional, or academic needs when they need them, without costly and elaborate labeling procedures standing in the way. An increasingly successful means of supporting students is the use of multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS). Most such systems include three tiers.Adelman, H. S., & Taylor, L. (2008). “School-Wide Approaches to Addressing Barriers to Learning and Teaching” in Doll, B., & Cummings, J. (Eds.). Transforming School Mental Health Services: Population-Based Approaches to Promoting the Competency and Wellness of Children. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. The first tier is universal—everyone experiences it. Ideally, it uses teaching strategies grounded in universal designs for learning that are broadly successful with children who learn in different ways, as well as using explicit social-emotional learning models and positive behavioral support strategies that are culturally and linguistically competent.Osher, D., Kidron, Y., DeCandia, C. J., Kendziora, K., & Weissberg, R. P. (2016). “Interventions to Promote Safe and Supportive School Climate” in Wentzel, K. R., & Ramani, G. B. (Eds.). Handbook of Social Influences in School Contexts (pp. 384–404). New York, NY: Routledge.

Tier 2 services and supports address the needs of students at elevated risk or who need some particular additional support. The risk may be demonstrated by behavior (e.g., number of absences) or due to having experienced a known risk factor (e.g., the loss of a parent). Services may include academic supports (e.g., Reading Recovery, mathematics tutoring, extended learning time) or family outreach, counseling, and behavioral supports. Schools may operate counseling groups to support students who have experienced loss, violence, or other traumatic events and those who need to learn to manage conflict and anger.

Tier 3 involves intensive interventions for students at particularly high levels of risk or whose needs are not sufficiently met by tier 2 interventions. Tier 3 services, often offered in collaboration with community-based organizations, can include one-on-one health and mental health supports, effective special education, and social workers to help students—and sometimes their families—access supports and services.

Interventions, not students, are tiered, and supports can and should be provided in normative environments. Students are not “tier 2 or 3 students”; they receive services as needed for as long as needed, but no longer. Providers should build on student strengths and assets, not focus solely on deficits. Because tier 2 and 3 services demand more of students and families, it is particularly important that they be implemented in a child- and family-driven manner that is culturally competent. Key is that a whole child approach is taken; students are dealt with in connected rather than fragmented ways; and care is personalized to the needs of individuals.

Recommendations

This growing knowledge base suggests that, in order to create schools that support healthy development for young people, our education system should focus on three major actions:

Recommendation #1: Focus the System on Developmental Supports for Young People

States guide the focus of schools and professionals through the ways in which accountability systems are established, guidance is offered, and funding is provided. To ensure developmentally healthy school environments, states, districts, and schools can:

- Include measures of school climate, social-emotional supports, and school exclusions in accountability and improvement systems, so that these are a focus of schools’ attention, and data are regularly available to guide continuous improvement.

- Adopt standards or other guidance for social, emotional, and cognitive learning that clarifies the kinds of competencies students should be helped to develop and the kinds of practices that can help them accomplish these goals.

- Replace zero tolerance policies regarding school discipline with discipline policies focused on explicit teaching of social-emotional strategies and restorative discipline practices that support young people in learning key skills and developing responsibility for themselves and their community.

- Incorporate educator competencies regarding support for social, emotional, and cognitive development, as well as restorative practices, into licensing and accreditation requirements for teachers and administrators, as well as counseling staff.

- Provide funding for school climate surveys, social-emotional learning and restorative justice programs, and revamped licensing practices (including appropriate assessments) to support these reforms. As suggested below, additional investments are needed for multi-tiered systems of supports, integrated student services, extended learning, and professional learning for educators to enable progress within schools.

Recommendation #2: Design Schools to Provide Settings for Healthy Development

To provide school settings for healthy development within a productive policy environment, educators and policymakers can:

- Design schools for strong, personalized relationships so that students can be well-known and supported (e.g., by creating small schools or learning communities within schools), looping teachers with students for more than 1 year, creating advisory systems, supporting teaching teams, and organizing schools with longer grade spans—all of which strengthen relationships and improve student attendance, achievement, and attainment.

- Develop schoolwide norms and supports for safe, culturally responsive classroom communities that provide students with a sense of physical and psychological safety, affirmation, and belonging, as well as opportunities to learn social, emotional, and cognitive skills.

- Ensure that integrated student supports are available to support students’ health, mental health, and social welfare through community school models or community partnerships, coupled with parent engagement and restorative justice programs.

- Create multi-tiered systems of support (MTSS), beginning with universal designs for learning and personalized teaching, continuing through more intensive academic and non-academic supports, to ensure that students can receive the right kind of assistance when needed, without labeling or delays.

- Provide extended learning time to ensure that students do not fall behind, including skillful tutoring and academic supports such as Reading Recovery; summer programs to avoid summer learning loss; and support for homework, mentoring, and enrichment.

- Design outreach to families as part of the core approach to education, including home visits and flexibly scheduled student-teacher-parent conferences to learn from parents about their children; outreach to involve families in school activities; and regular communication through positive phone calls home, emails, and text messages.

Recommendation #3: Ensure Educator Learning for Developmentally Supportive Education

To help educators learn how to redesign schools and develop practices that support a positive school climate, the state, counties, districts, schools, and educator preparation programs can:

- Invest in educator wellness through strong preparation and mentoring that improve efficacy and reduce stress, mindfulness and stress management training, social-emotional learning programs that benefit both adults and children, and supportive administration.

- Design pre-service preparation programs for both teachers and administrators that provide a strong foundation in child and adolescent development and learning; knowledge of how to create engaging, effective instruction that is culturally responsive; skills for implementing social-emotional learning and restorative justice programs; and an understanding of how to work with families and community organizations to create a shared developmentally supportive approach. Include supervised clinical experiences in schools that model how to create (and for administrators, how to design and foster) a positive, developmentally supportive school climate for all students.

- Offer widely available in-service development that helps educators continually build on and refine student-centered practices; learn to use data about school climate and a wide range of student outcomes to undertake continuous improvement; problem solve around the needs of individual children; and engage in schoolwide initiatives in collegial teams and professional learning communities.

- Invest in educator recruitment and retention, including forgivable loans and service scholarships that support strong preparation, high-retention pathways into the profession—such as residencies—that diversify the educator workforce, high-quality mentoring for beginners, and collegial environments for practice. A strong, stable, diverse, well-prepared teaching and leadership workforce is perhaps the most important ingredient for a positive school climate that supports effective whole child education.

The emerging science of learning and development makes it clear that a whole child approach to education, which begins with a positive school climate that affirms and supports all students, is essential to support academic achievement as well as healthy development. Research and the wisdom of practice offer significant insights for policymakers and educators about how to develop such environments. The challenge ahead is to assemble the whole village—schools, health care organizations, youth and family serving agencies, state and local governments, philanthropists, and families—to work together to ensure that every young person receives the benefit of what is known about how to support his or her healthy path to a productive future.

Educating the Whole Child: Improving School Climate to Support Student Success by Linda Darling-Hammond and Channa Cook-Harvey is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

We are grateful to The California Endowment for its funding of this report. Funding for this area of LPI’s work is also provided by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, and the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Ford Foundation.

Photo copyright Drew Bird - www.drewbirdphoto.com