Federal and State Resources for Students Experiencing Homelessness

Summary

Approximately 1.3 million public school students in the United States were identified by their schools or districts as experiencing some form of homelessness in 2019–20. The housing instability faced by these students is associated with a range of acute needs, including transportation, food security, health care, and emotional and mental health. These challenges have negative impacts for student learning and are associated with lower academic achievement and attainment. This brief reviews major federal and state sources of funding for students experiencing homelessness. It finds that federal funding is insufficient to achieve the goals of federal law and is unevenly distributed. Further, only four states provide dedicated funding to support students experiencing homelessness. Recommendations include increases in funding and an entitlement formula for the McKinney-Vento Act (the main source of federal funds), as well as expansion of allowable uses of funds to cover acute needs, and more informative data about resource use.

The report on which this brief is based, which includes state-level per-pupil estimates of McKinney-Vento funding, can be found here.

Introduction

Approximately 1.3 million public school students in the United States were identified by their schools or districts as experiencing some form of homelessness in 2019–20. Because of factors such as inequitable access to housing and economic opportunity, rates of homelessness tend to be higher among students of color. Due to their unstable living situations, students experiencing homelessness often have additional educational, social, emotional, and material needs compared to their stably housed peers. Housing instability can result in increased absences from school and can lead to students changing schools midyear. Each school move can disrupt students’ education and limit opportunities to learn. Moreover, housing instability and severe poverty can lead to food instability and complicate efforts to receive needed health services.

The multiple challenges associated with homelessness have major implications for student learning outcomes. Reading, mathematics, and science scores for students experiencing homelessness tend to be lower than those of their peers, including those from economically disadvantaged but residentially stable families. For example, in 2018–19, just 30% of students experiencing homelessness reached academic proficiency on state standards in reading and language arts, compared to 38% of their economically disadvantaged peers. Performance was lower, and the gap was even larger, in mathematics and science. The experience of homelessness also significantly reduces the likelihood that students will graduate and go on to college.

Because of the multiple challenges they often face, students experiencing homelessness need access to a range of services. The major federal educational effort to provide and coordinate these supports and establish rights for students experiencing homelessness is Title VII, subpart B, of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act. This law sets out the responsibilities for local educational agencies (LEAs)—such as traditional school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education—to ensure that students experiencing homelessness “have access to the same free, appropriate public education” as other children. LEAs—regardless of whether they receive McKinney-Vento funding—must designate a district homeless liaison. The liaisons’ responsibilities include identifying and immediately enrolling students experiencing homelessness; ensuring their full participation in school; providing transportation to and from school regardless of where they are currently residing; informing the community and parents of the rights of children experiencing homelessness; and referring them to key resources, such as housing, medical, dental, and mental health services.

There is a need for focused attention on the most vulnerable students, including those experiencing homelessness, particularly as the nation seeks to recover from the pandemic. However, districts face barriers in supporting students experiencing homelessness. These barriers include unstable funding or funding that is inadequate to meet student needs, and restrictions on the allowable uses of federal funds, which limit district ability to support noneducational expenses, such as for emergency housing.

Identification of students experiencing homelessness can also be challenging. Homelessness can be a fluid situation, with students experiencing homelessness at different times during the school year and for various amounts of time. Students and parents may not wish to identify themselves as experiencing homelessness for fear of stigmatization and bullying. In addition, schools and districts may not have the systems or capacity to identify student homelessness or to make families aware of their rights and the services available to them. Prior research has found that funding may help districts identify students experiencing homelessness,Hallett, R. E., Skrla, L., & Low, J. (2015). That is not what homeless is: A school district’s journey toward serving homeless, doubled-up, and economically displaced children and youth. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 28(6), 671–692. and without sufficient funding, fewer students are able to be identified as needing support, and services may be inadequate. For example, a 2019 report on district liaisons in California found that many liaisons held multiple roles in their districts, further restricting the time available in their capacity as liaisons.Piazza, A., & Hyatt, S. (2019). Serving students hidden in plain sight: How California’s public schools can better support students experiencing homelessness. ACLU Foundations of California and California Homeless Youth Project.

This brief summarizes key findings from a study that examined the federal and state financial supports for students experiencing homelessness. To determine federal financial resources, we collected information on the various federal education programs designed to assist students experiencing homelessness. To assess state funding, we reviewed all 50 state school funding formulas to ascertain what funding, if any, states provide to student homelessness programs.The majority of this publication uses 2019–20 funding and student count data given that the number of students identified as experiencing homelessness during 2020–21 was impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. The National Center for Homeless Education recommends using caution with using 2020–21 data.

Our review found that while the federal government has been increasing funding for students experiencing homelessness over the past several years, the level of funding remains meager relative to the need. Moreover, only four states supplemented federal dollars with additional funding to support students experiencing homelessness. These findings suggest the need for policy changes concerning funding amounts, distribution, and data collection that may improve educational opportunities for these students.

Federal Funding for Students Experiencing Homelessness

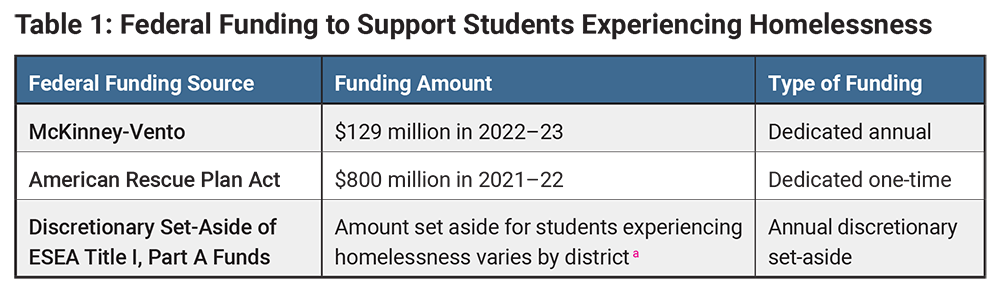

There are three primary federal funding sources to support students experiencing homelessness (see Table 1). The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act is the major federal funding source to support the work of district liaisons and services for students experiencing homelessness. Federal funds are also available through the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), which requires states and LEAs to plan for how they will support students experiencing homelessness. It also requires LEAs to set aside a portion of their ESEA Title I, Part A dollars for services to these students. Additionally, the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) included funding targeted specifically toward students experiencing homelessness.

Sources: U.S. Department of Education. (2022). Department of Education budget tables; American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, H.R.1319, 117th Cong. (2021); 20 U.S.C. § 6313(c)(3)(C) (2022).

McKinney-Vento Funding Is Insufficient to Achieve the Goals of the Act and Is Unevenly Distributed

The major federal educational effort to support students experiencing homelessness is the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act of 1987. This law provides annual grants to states to support programs for students experiencing homelessness. Between 2010 and 2023, funding for the McKinney-Vento program increased from $65.4 million to $129 million, a $63.6 million (97%) increase. Despite these increases, the McKinney-Vento investment remains small in terms of dollars per student experiencing homelessness. Between 2010 and 2020, the population of students experiencing homelessness increased by 39%. Funding for the McKinney-Vento program also increased from $65.4 million to $101.5 million, a $36.1 million increase, between the same years. This 55% increase, however, moved the funding level from only $71 per identified pupil to $79 per identified pupil, a small fraction of what districts must actually spend to meet students’ needs. For example, a recent study of five districts’ efforts to support students experiencing homelessness found that each of them supplemented McKinney-Vento funding with private grants and donations.Levin, S., Espinoza, D., & Griffith, M. (2022). Supporting students experiencing homelessness: District approaches to supports and funding. Learning Policy Institute.

This per-pupil amount corresponds to the number of students that schools have identified as experiencing homelessness, not the actual number of students experiencing homelessness—which is greater. Improved identification would yield a still lower federal per-pupil amount, underscoring the extent of need. While funding is not distributed to states on a per-pupil basis, attention to this amount is helpful to underscore the level of inadequate funding. To put these funds into perspective, in the 2020–21 school year, public schools received just over $801.6 billion in revenue from local, state, and federal sources—which means that McKinney-Vento funding accounted for just over 1/100th of 1% (0.013%) of the revenue that schools received, even though students identified as experiencing homelessness comprise 2.5% of all students and have a wide variety of needs.National Education Association. (2021). Rankings of the states 2020 and estimates of school statistics 2021; U.S. Department of Education. (2021). Fiscal year 2019–20 state tables for the U.S. Department of Education, state tables by program.

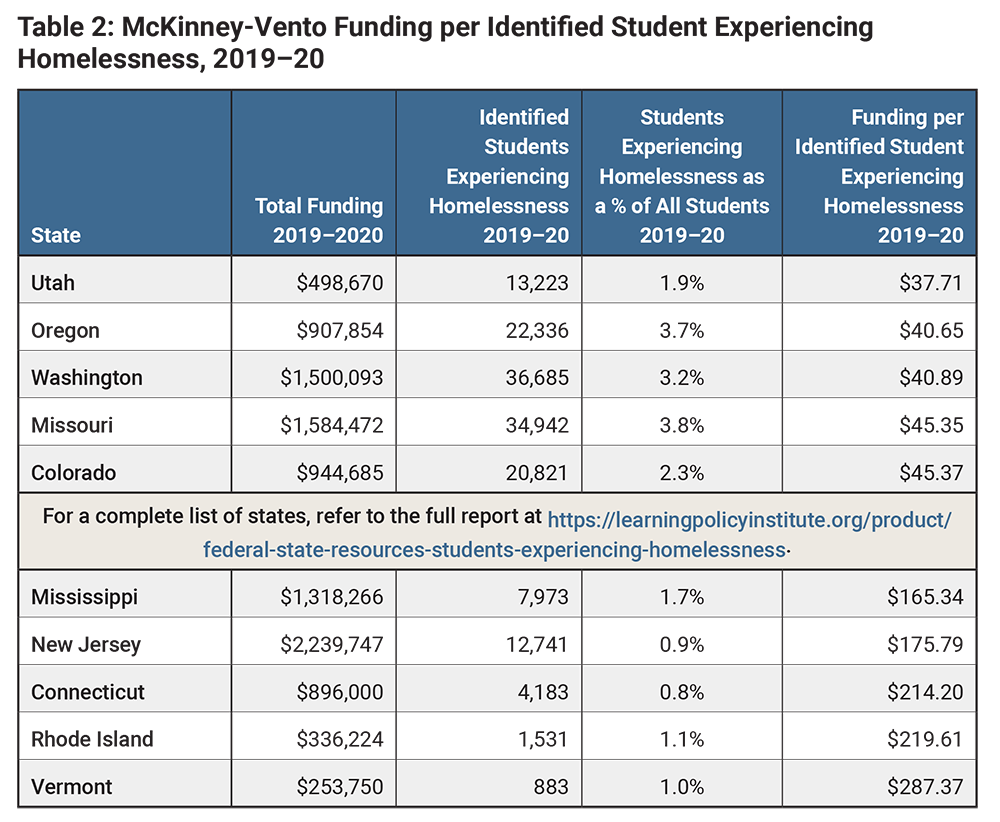

States do not receive federal funding based on the number of students experiencing homelessness, and most districts serving students experiencing homelessness do not receive federal funds to support them. McKinney-Vento funds are distributed to states based on their proportions of Title I, Part A funding. Because the funding formula is not based on the number of students identified as experiencing homelessness, there is large variation in the per-pupil amount each state receives to support students experiencing homelessness—ranging from $38 in Utah to $287 in Vermont. (See Table 2.)

Further, because states distribute these limited funds to districts through a competitive grant process, the amount of funding is not proportional to the number of students served, and most districts do not receive such grants at all. In fact, fewer than 24% of local educational agencies (LEAs) (4,497 out of 18,844) receive them. For example, in 2019–20, of the 10 districts in California with the highest number of students experiencing homelessness, only 5 received a district grant, and per-pupil allocations for districts receiving funding ranged from $24.35 to $50.72. Meanwhile, San Diego Unified, the district serving the second-largest number of students experiencing homelessness in the state—over 8,000 students—received no McKinney-Vento funding.Learning Policy Institute analysis of Cumulative Enrollment Data, 2019–20, from the California Department of Education (accessed 10/13/22). Information about McKinney-Vento funding is available from the California Department of Education (accessed 11/23/22). Note: Districts without federal McKinney-Vento funding either did not apply for, or were not awarded, a McKinney-Vento district subgrant.

Funded districts tend to be larger, serving proportionately more students, including students experiencing homelessness; in 2019–20, the districts that received McKinney-Vento funding educated approximately 63% of all students identified as experiencing homelessness.Learning Policy Institute calculation of data from the U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). EDFacts data files (SY 2019–20 homeless students enrolled). Note this is an estimate because these data may have some duplication of students experiencing homelessness who attended multiple LEAs, and some LEAs in a state did not report homelessness enrollment data. Despite their size, of the districts that did receive McKinney-Vento funding, the average district grant was only $21,455.Learning Policy Institute calculations based on data from the National Center for Homeless Education (2021) and the U.S. Department of Education (2021). Funding for states in 2020–21 equated to $100,905,220. This amount was divided by 3,695—the number of school districts receiving funding in 2020–21. This number may be an underestimate, as some grants are awarded to a consortium of districts. And over one third of all identified students experiencing homelessness were educated in districts that did not receive a McKinney-Vento grant.

Data sources: Learning Policy Institute calculations based on data collected by the National Center for Homeless Education. National Center for Homeless Education. (2021). Student homelessness in America: School years 2017–18 to 2019–20. (accessed 03/23/22); U.S. Department of Education. (2021). Budget history tables. (accessed 12/02/22).

For a complete list of states, refer to the full report.

Little Is Currently Known About Discretionary ESEA, Title I Set-Aside Amounts

The federal government requires LEAs to set aside some ESEA Title I, Part A funding for programs serving students experiencing homelessness and other high-need students. However, until recently, little data was collected on these amounts. Starting in the 2022–23 school year and for the following 2 school years, the U.S. Department of Education will require state education agencies (SEAs) to report how much funding LEAs are reserving under the Title I set-aside to support students experiencing homelessness and the number of students served.Office of Management and Budget. EDFacts data collection, school years 2022–23, 2023–24, and 2024–25 (with 2021–22 continuation). OMB: 1850-0925. LEAs may determine the set-aside amount “based on a needs assessment of homeless children and youths in the local educational agency, taking into consideration the number and needs of homeless children and youths.”20 U.S.C. § 6313(c)(3)(C) (2022). Because LEAs are not required to base their Title I set-asides on a needs assessment, there is no consistent, data-based approach for LEAs to determine how much funding to target for students experiencing homelessness. The lack of such a system could result in a wide variation in the amount of funding each district sets aside for students experiencing homelessness.

ARPA Support for Students Experiencing Homelessness Was a One-Time Investment

The most generous investment at the federal level to support students experiencing homelessness was a temporary, one-time investment through ARPA. The law allocated $800 million in one-time funding to states to support students experiencing homelessness, distributed as two sums: The first $200 million was distributed to LEAs on a competitive basis; the second was awarded to LEAs according to formula subgrants that were based on Title I, Part A payments and districts’ identified enrollment of students experiencing homelessness, whichever was greater. ARPA represents a major investment. Although these were one-time funds and not all districts received similar per-pupil amounts, the total funding equated to about $625 per student experiencing homelessness based on 2019–20 student counts.

State Funding for Students Experiencing Homelessness

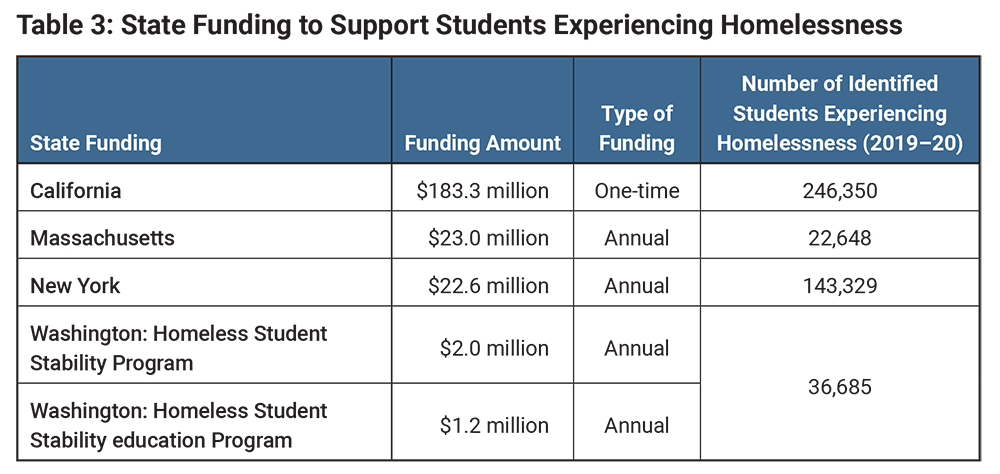

Only four states have allocated resources specifically to support students experiencing homelessness (see Table 3). In 2021, California appropriated $183.3 million in one-time pandemic relief funding to districts through allocations of $1,000 per student experiencing homelessness. Massachusetts’ school funding formula includes a $23.0 million transportation reimbursement for school districts providing transportation that supports students experiencing homelessness who attend their school of origin. New York allocated $22.6 million to support the education and transportation of students experiencing homelessness in fiscal year 2023. Washington state’s Homeless Student Stability Program provides $3.2 million across two competitive grants to provide educational stability by promoting housing stability within school districts; to increase identification of students experiencing homelessness; and to encourage the development of sustainable, collaborative strategies between housing and education partners.

Annual state funding ranges from $87 per identified student experiencing homelessness in Washington to $1,016 in Massachusetts. These additional state dollars are helpful but may not be adequate to meet student needs. For example, a 2019 Washington state audit estimated that school districts spend $28.6 million on essentials such as homeless liaison positions, professional development, and student transportation, yet are provided only $2.5 million in funding.Office of the Washington State Auditor. (2019). Performance audit: Opportunities to better identify and serve K–12 students experiencing homelessness

Policy Recommendations

The findings point to lack of funding as one of the primary barriers to providing students experiencing homelessness with the education they are entitled to and need. Because the most effective way to mitigate the negative effects of experiencing homelessness on students is to prevent it, policymakers should ensure that financial resources are available to communities and schools to help keep students housed.

In addition to adopting policies that help students avoid experiencing homelessness, federal and state policymakers can consider increasing funding, making changes to funding distribution, expanding allowable uses of federal funding, and improving the quality of information about the use of funds. Four potential strategies include:

- Increase federal and state funding to help local educational agencies (LEAs) implement the federal protections, services, and supports afforded to students experiencing homelessness. Policymakers at both state and federal levels should consider increasing their investments to support students experiencing homelessness. Funding should consider LEAs’ costs associated with meeting the multiple needs of students experiencing homelessness. These may include a district homeless liaison; school-level liaisons; transportation; supplies; and providing ready access to a web of supports, such as social-emotional, academic, health, nutrition, and housing services.

- At the federal level, annual funding for the McKinney-Vento program ($129 million for fiscal year 2023) should be substantially increased to allow LEAs to meet the law’s mandates. While additional research is needed to help determine the exact amount of funding necessary to support the educational needs of students experiencing homelessness, a good starting point would be to use the $800 million in funding provided by the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) for student homeless programs as a baseline for future annual financing, which would amount to approximately $625 per student experiencing homelessness, based on pre-COVID-19 counts.

- At the state level, states should provide consistent funding that complements federal funds and is targeted to local needs. State policymakers have several potential vehicles for funding assistance that supports students experiencing homelessness, including developing a student funding formula that includes an additional weight for these students, providing a targeted annual allotment for needed services such as transportation or social supports, and providing grants to communities to coordinate services across local agencies. Whichever approach is used, the funding should be consistent and designed to supplement federal funding in ways that address acute needs in the given state and local contexts.

- At the federal level, annual funding for the McKinney-Vento program ($129 million for fiscal year 2023) should be substantially increased to allow LEAs to meet the law’s mandates. While additional research is needed to help determine the exact amount of funding necessary to support the educational needs of students experiencing homelessness, a good starting point would be to use the $800 million in funding provided by the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) for student homeless programs as a baseline for future annual financing, which would amount to approximately $625 per student experiencing homelessness, based on pre-COVID-19 counts.

- Consider revising the McKinney-Vento funding formula to target funds, at least in part, based on the enrollment of students experiencing homelessness. The current McKinney-Vento funding level, its allocation formula, and competitive grant process result in too few dollars, wide variation in the amount of funding to states per student experiencing homelessness, and most districts not receiving any of these federal funds. Thus, in addition to increasing the overall McKinney-Vento funding levels, shifting the allocation formula away from using only a competitive grant structure and toward an entitlement model based—at least in part—on the number of students identified as experiencing homelessness in each LEA could help distribute funds to support far more students’ needs. The recent allocation of $800 million in ARPA funds for students experiencing homelessness, which combined competitive grants with formula-driven funding, was a step in this direction. In addition, because many districts are unable to identify all of their students experiencing homelessness, a new funding formula might initially take into account poverty levels as well as numbers of students identified as experiencing homelessness. A revised formula that provides more stable and predictable funding from year to year could help districts better meet the needs of students experiencing homelessness.

- Expand allowable uses of federal funds for supporting students and families experiencing homelessness. Federal policymakers could also increase supports for students experiencing homelessness by better aligning the federal definitions of “homeless” used by federal housing and education programs. Using different definitions can make it difficult for local agencies to provide comprehensive wraparound supports to students and their families experiencing homelessness. Federal policymakers could align the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) definition of “homeless” used for homeless assistance programs with the one established by the McKinney-Vento Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program. This would enable students who are living in motels or who are staying doubled up with other families to qualify for housing and homeless assistance, administered by HUD.

Another strategy for increasing supports is to expand the allowable uses of funds of the McKinney-Vento Education for Homeless Children and Youth Program. This might include allowing payment for emergency utilities or rent, emergency medical expenses that compete with rent, or emergency hotel stays when no shelter is available. These supports may help prevent students and their families from becoming unhoused or facing a disruptive move.

- Improve the quality of information about the use of funds to assist students experiencing homelessness. States and LEAs could help improve supports for students experiencing homelessness by promoting greater use of data on existing uses of funds in order to inform technical assistance and continuous improvement. Starting in the 2022–23 school year and for the following 2 school years, the U.S. Department of Education will require state education agencies (SEAs) to report how much funding LEAs are reserving under the Title I set-aside to support students experiencing homelessness and the number of students served. The Department of Education could make this reporting permanent and also require LEAs to report data to SEAs about how they are spending the funds. SEAs could leverage McKinney-Vento’s state reservation to support capacity to review these data. SEAs could use data to identify promising approaches to disseminate and to guide technical assistance to all LEAs, including those not yet receiving McKinney-Vento funding.

Federal and State Resources for Students Experiencing Homelessness (brief) by Daniel Espinoza, Michael Griffith, Dion Burns, and Patrick M. Shields is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Raikes Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.