New Mexico Community School Profile: Roswell Independent School District

Summary

As of 2024–25, Roswell Independent School District has four community schools, including Sierra Middle School—entering its fifth year of implementation—and University High School—an alternative school entering its third year of implementation. Sierra and University High have each created a nourishing school climate and culture by providing culturally responsive and restorative spaces, expanding opportunities for student voice and engagement, and stitching together a social safety net to address out-of-school learning barriers. Key accomplishments include a reduction in substance abuse at both sites (a focus identified by the community school site-based leadership teams), along with improvements in the graduation rate and disciplinary incidents at University High and improvements in staff retention and student reports of feeling cared for by an adult at Sierra.

Introduction

[University High School] change[d] my perspective about my life. When I moved here, it changed my whole mindset. I didn’t use to go to school; now I go to school every day. I used to get straight F’s. Now I get A’s and B’s. It’s just a really good school.

A transformation has been underway at University High School (University High) in Roswell, NM, since it became a community school in 2022–23. Educators and students are collaboratively creating spaces of belonging, safety, and care using the community school strategy (see What Is a Community School?). The adoption of restorative practices, the centering of student voice, and the attention to students’ holistic needs have reinvigorated the school community. Shifting popular career pathway courses to the beginning of the day helped engage more students, particularly those with jobs outside of school. In 2023–24, the second year of implementation, student fights became almost nonexistent (from more than 10 per semester to only 1 the whole school year). Learning days lost to suspensions dropped dramatically, from 274 in 2022–23 to 61 in 2023–24. The 4-year graduation rate rose from 36% in 2022 to 55% in 2023, a level maintained in 2024.

While just a few years ago University High students and the broader Roswell community generally perceived the school as struggling, students now proudly note that their school has trades and career technical education pathways along with opportunities to graduate with industry certifications (e.g., in hospitality, electrical engineering, cosmetology, clean energy, and medical care). Students recently organized the first prom in over a decade. The school provides an in-house daycare for student parents, also allowing hands-on child care training for interested students. It is a holistic conception of a community school, a place where students see themselves as part of a collective family.

New Mexico has taken important steps to support the implementation and scaling of community schools in Roswell and statewide. Since 2019, $36.9 million in community schools funding has been allocated to the New Mexico Public Education Department (PED) for grant funding, grant management, and technical assistance. The funds have allowed the strategy to spread across the state. For the 2024–25 school year, 90 schools either received funding for implementation grants or were designated to participate in the Accredit Pilot Program.

What Is a Community School?

The New Mexico Public Education Department (PED) defines a community school as “a whole child, comprehensive strategy to transform schools into places where educators, local community members, families, and students work together to strengthen conditions for student learning and healthy development. As partners, they organize in- and out-of-school resources, supports, and opportunities so that young people thrive.”

While programs and services at each community school vary according to local context, PED has identified six key site-level practices that are grounded in research and the expertise of community school practitioners participating in the national Community Schools Forward task force. These are (1) expanded, culturally enriched learning opportunities; (2) rigorous community-connected classroom instruction; (3) a culture of belonging, safety, and care; (4) integrated systems of support; (5) powerful student and family engagement; and (6) collaborative leadership, shared power and voice.

These whole child practices are best implemented when there is a shared vision and purpose, trusting relationships are formed between members of the school community, and decision-making is both data-informed and inclusive. Research from the Learning Policy Institute and RAND shows that well-implemented community schools can improve students’ attendance, behavior, engagement, and academic outcomes, including test scores and graduation rates.

Source: New Mexico Public Education Department. Community schools.

The Learning Policy Institute team has worked with New Mexico education partners, including the Southwest Institute for Transformational (SWIFT) Community Schools and the Albuquerque/Bernalillo County (ABC) Community School Partnership, to conduct research supporting implementation of New Mexico’s community school grants. This profile is part of a series documenting community schools implementation in three districts across the state—Albuquerque, Peñasco, and Roswell. These profiles draw on interviews, site visit observations, and a review of relevant documents to highlight the structures and processes school and district staff, together with community partners, have developed to support student thriving and family well-being.

Roswell Independent School District

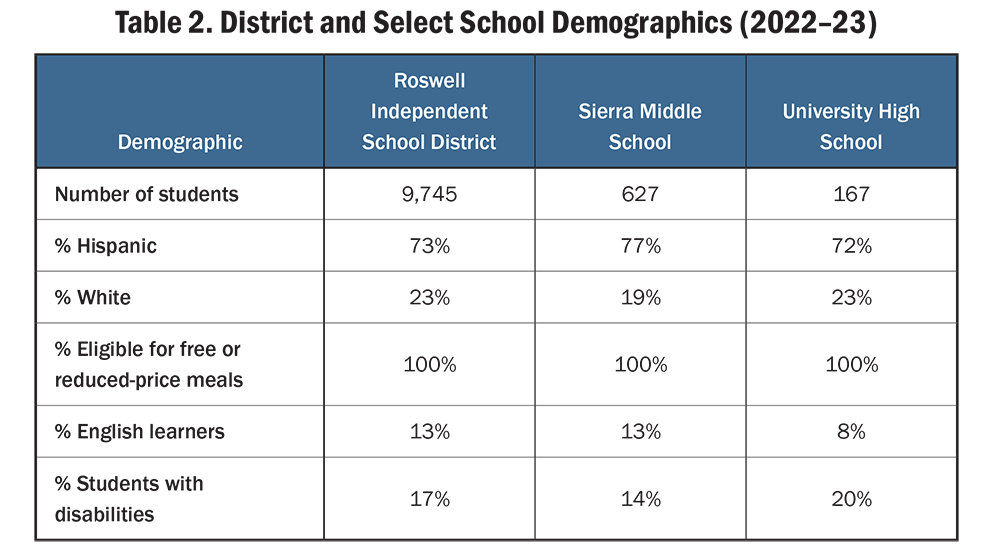

Roswell is a city of nearly 50,000 people located in southeast New Mexico. Roswell Independent School District (Roswell) serves about 10,000 students in its 21 schools, which include 12 elementary schools, 4 middle schools, 4 high schools, and a preschool. One K–8 charter school is also authorized by the district.

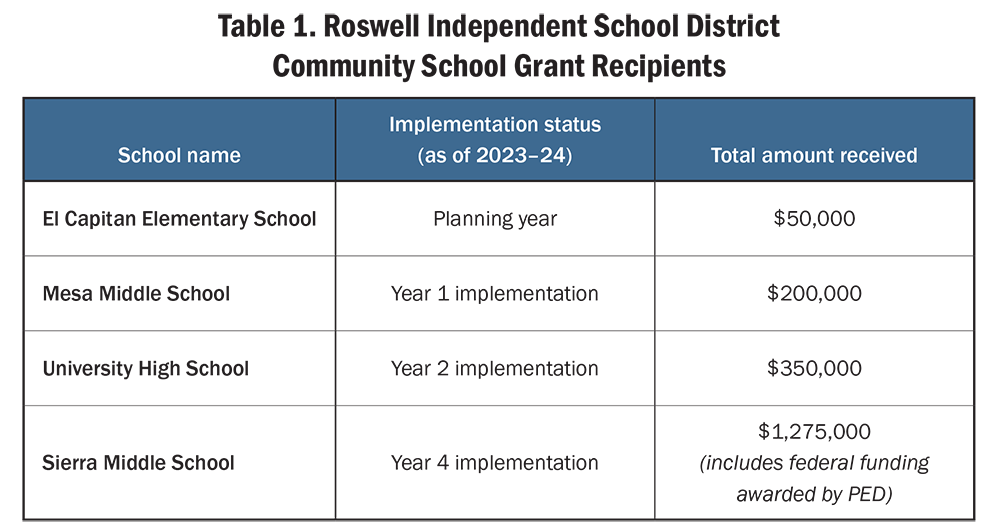

In 2020, Roswell’s Sierra Middle School (Sierra) received $1 million in federal school improvement funding from PED to support community school implementation, becoming the first community school in the district. Following a robust community engagement process that included outreach to neighbors, the funds largely went toward building a school-based health center and purchasing equipment for a career exploration class. As of the 2023–24 school year, four schools in Roswell had received state community school grants (see Table 1). In addition, for the 2024–25 school year, the district received $250,000 to allocate across the four community school sites. Sierra was also designated to participate in the PED Accredit Pilot Program for community schools that previously received renewal grants.

Roswell’s district office is supporting its four community school sites by prioritizing collaboration and striving for coherence and integration across related initiatives and programs. For example, district staff are working to strategically integrate the community schools strategy with the multi-layered system of supports (MLSS) and positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS) so those interventions can work together and build from one another instead of remaining separate and siloed. The district is also improving its current student data system, which will help school sites identify needs, establish goals, and monitor improvement. Additionally, the district hosts monthly community school meetings with district staff, principals, and coordinators, and weekly coordinators-only meetings, to provide professional development, support, and opportunities for site leaders to learn from and collaborate with one another. Coordinators and principals shared that these meetings reduce feelings of isolation. Rather than feeling like they are implementing the community schools strategy in a “bubble,” they are regularly connecting with knowledgeable colleagues they can lean on for support.

This profile explores two of Roswell’s four community schools: Sierra Middle School (the district’s first community school) and University High School, an alternative school that has shown impressive results since adopting the community schools strategy in 2022–23. Table 2 shows demographic information for Roswell at the district level and for both schools featured in this brief.

Nourishing School Climate and Culture Through Roswell’s Community Schools Strategy

Through their community school grants, Sierra and University High have both focused on strengthening school climate by creating a culture of belonging, safety, and care—one of the six key practices identified by the New Mexico Public Education Department. At Sierra, a community school needs and assets assessment conducted during the 2019–20 school year identified school climate as a priority area. In a survey of the entire student body, just 4% of students said they had a caring adult in their life who regularly checks on them. As detailed in the introduction of this brief, University High students also identified improving school climate as a top priority.

Alongside developing a culture of belonging, safety, and care—including through the provision of culturally responsive and restorative spaces for students—Sierra and University High are implementing additional key practices identified in the PED community schools framework. These key practices include expanding student engagement and collaborative leadership opportunities and stitching together a social safety net through integrated systems of support.

Providing Culturally Responsive and Restorative Spaces

Developing a culture of belonging, safety, and care in Roswell community schools means attending to the linguistic and cultural needs of each school community as well as equipping students with the necessary skills to maintain healthy relationships.

For multiple years, the front office staff at Sierra did not speak Spanish. In a school where more than three quarters of families identify as Hispanic and many speak Spanish at home, unsurprisingly, Spanish-speaking families did not always feel welcome. That began to change when the school hired a native Spanish-speaking community school coordinator who has lived in Roswell for nearly 2 decades. On a typical day, she greets families by name as they walk through the school’s front doors and texts with other families in Spanish and English to check in and ask how they are doing. She explained her style of supporting families:

I don’t directly ask, but I just kind of go with the conversation. “Oh, well, you know, I can help you with this; or I know this person.” It’s more like just having a normal conversation but still being attentive to those little cues that they send and then [thinking], “OK, that’s a flag. That’s where I can help you.”

Part of the job as well is to bond with students and develop trusting relationships. For example, when a student faced disciplinary consequences at school while experiencing stressful challenges at home, the University High coordinator shared this context with the principal and helped to implement a more restorative disciplinary approach.

Teachers at Roswell community schools also prioritize developing authentic relationships with students. For example, as University High became a community school, teachers redoubled their efforts to take advantage of the small learning community. Multiple University High students shared comments like “The teachers work with you individually,” “They take their time,” and “[They] are willing to work with you, even on their prep periods.” Perhaps most tellingly, one student admired that the teachers at University High “are willing to work with you even when you are not willing to work with them. They try to push you as much as they can.” These individualized, trusting relationships are a significant part of how staff and students at University High are transforming the school culture with the help of the community schools strategy.

In addition to the challenges with fights and poor school climate at University High mentioned in the introduction, Sierra staff expressed concerns about bullying. As one school administrator noted, “A lot of times we don’t give kids credit for being able to solve problems, and teachers want to take over and just [say], ‘OK, this is what we’re doing.’” Over time, the school’s shift toward restorative justice has helped educators gain the skills to support students to resolve conflicts themselves. Another administrator described it this way, “We’re teaching them how to solve their issues. And a lot of them are getting to the point where they just want to say something to a person in a calmer environment, and so we offer that.” An educator continued, “It’s … teaching them that there is another outlet. And so we even have kids come ask for mediation now.” These school efforts are helping equip students and teachers to solve problems more effectively.

Expanding Opportunities for Student Voice and Engagement

Community schools implementation in Roswell coincided with a return to in-person learning amid the COVID-19 pandemic. At that time, student engagement was low. One district administrator described students as walking the halls like “zombies.” Amid rising mental health challenges and increased student absenteeism, educators at both Sierra and University High felt part of the solution was to shift structures and practices to allow students to be increasingly active in making decisions related to their education. (Community partners have also been part of the solution, which is explored in the next section.) As one district administrator shared, “The people closest to the work have to give input to the work, and so often as adults we forget to include the students.”

Now, all after-school clubs at Sierra are determined by students. A school staff member described how students met this shift with enthusiasm: “This was a big thing for them. They feel like they’re valued. They feel like, ‘Oh, my opinion matters!’” Students are in charge of brainstorming club ideas and gathering names of peers interested in participating. With sufficient interest, they then identify a teacher willing to host the club—the additional contract hours are paid for using community schools grant funding. From there, students meet with the community school coordinator and the principal to seek approval establishing a new club. The most popular club on campus by far is Anime Club. Other clubs with passionate followings include Earth Club, Lego Club, Harry Potter Club, and Young Birders Club.

Students also stay after school on a voluntary basis to attend Homework Help. “I have kids who will go 4 out of the 5 days of the week. … They stay because they want to [improve] their grade,” a staff member noted. Simply shifting the name from tutoring to Homework Help made a positive impact on attendance by removing the negative stigma and encouraging students to advocate for themselves.

These small shifts in student engagement resulted in bigger ripples across the school. Sierra teachers spoke about how additional opportunities to engage in fun activities with students strengthened adult–student relationships. The additional programming also led to quieter pickup times after school, allowing for more meaningful conversations with caregivers collecting their students. Increased student autonomy after school also created space for more student voice during the regular school day. For example, the student body voted on and decided all events held during Teacher Appreciation Week; students were especially excited to see teachers dressed as Star Wars jedis or X-wing pilots during Fandom Day. It was a validation of student interests and a way to show respect, support, and excitement for their decisions.

At University High, the elected group of students comprising the student senate are the representative group for student voice, a collaborative leadership structure. And they take the role seriously, relishing the responsibility of participating in school decision-making. Even in its first year, the impact of this group has been wide ranging. For example, the student senate established and took responsibility for weekly school announcements. Prior to this, students had little opportunity to learn about upcoming school events and general happenings. In another example, senate representatives noticed that many students struggled with accessing hygiene and health products. They worked with the community school coordinator to secure funding and school board approval to create “Worry Walls,” a collection of health and hygiene products available in school bathrooms. The student senate helps operate monthly food distributions for students, their families, and other members of the community.

The group has also helped organize school field trips, a key way the school is expanding students’ horizons beyond Roswell while providing an incentive to do well on attendance, behavior, and grade requirements. One of the senate’s greatest accomplishments was advocating for and planning the school’s first prom in at least a decade. They organized fundraisers, booked a DJ and caterer, and prepared decorations. The event was a huge success and helped students access a teenage rite of passage that they had previously been missing.

Stitching Together the Social Safety Net

While focusing on strengthening the internal climate and culture, Sierra and University High have also worked with partners to simultaneously address the many out-of-school barriers that Roswell students and families face, including high levels of community trauma, violent crime, and poverty (see Community School Partners at Sierra Middle School and University High School).

The community school coordinators at Sierra and University High help students and families meet their basic needs by hosting monthly food distributions, creating on-campus clothing closets, and assisting new arrivals with resources and referrals. As one coordinator noted, “My main priorities are looking at the gaps and seeing how I could fill them. That’s how I see my job.”

Greater access to therapy is another immediate priority for both schools. As a district administrator noted, “Knowing that our students in New Mexico and in our district come to school with a higher rate of [adverse childhood experiences] than any other state means we have to do more to support behavioral and mental health.” Especially with the return of in-person learning, staff noticed that students were coping with increased mental health challenges.

The district hired a school-based therapist who rotates to various schools to provide therapy. Group therapy has been critical, as it allows schools to increase the number of students they can serve. The need to address widespread trauma is made plain by the fact that each school’s grief group therapy session is filled beyond capacity. One district educator shared:

One of the things I asked the therapist to do when I hired her was to do a grief therapy group. ... To be able to qualify to get into the group you had to lose an immediate family member in the last 6 months. It had to be an unexpected, traumatic death, so like a motor vehicle accident, homicide, suicide. Not cancer, not old age. Every single school was on a waiting list of kids to get in because there are that many students that have experienced high-trauma loss in the last 6 months of their life.

Access to therapy at school fills a gap in the community, given that minimal mental health supports exist to serve the level of need. Outside of school, a crisis appointment might be feasible within 4–6 hours; however, a student may have to wait up to 2–3 months for any kind of follow-up appointment with a mental health professional. At Sierra and University High, students are able to more quickly sign up for a session with the school-based therapist via QR codes. The principal of Sierra spoke of the importance of improving access to therapy: “It gives [students] a feeling of trust with the community that there are other people … in this world that will help them.” Unfortunately, due to reduced state grant funding, the district is unable to employ a therapist for the 2024–25 school year.

Physical health partnerships at the district’s community schools are critical because accessing basic health care in Roswell is also a challenge. For example, no vision provider in the community accepts Medicaid, and multiple health clinics in Roswell have closed. To drive through town is to see multiple clinics boarded up, weeds overtaking the dormant parking lots. The Sierra principal explained:

I haven’t been able to get in to [see] a doctor for over 6 months. ... I can’t imagine what my parents [at my school] are going through with [their] kids, because I know what hoops to jump through and a lot of our parents aren’t able to traverse those hoops.

Using federal community schools funding awarded by PED in 2020, Sierra built a professional-grade health center housed in a trailer unit adjacent to the school track, complete with multiple patient rooms, secure storage for prescription medicine, and office space for practitioners. Unfortunately, the space went unused during the 2023–24 school year after the previous medical provider ended the contract. While securing a new partner has been challenging, in fall 2024 the district signed an agreement with a new provider for the 2024–25 school year.

In addition to the health center, Sierra and University High staff have partnered with Walmart to provide free vision screenings. An optometrist comes from Albuquerque to provide glasses for students. A dentist visits twice per year to do cleanings and fill cavities. Each health provider is busy seeing students the entire time they are on campus.

The Sierra and University High school communities also had concerns about substance abuse issues among students (specifically vaping). Staff and students noted the pervasive smell of nicotine in bathrooms, and the peer pressure to vape was negatively impacting school culture. Given the range of impacts, the site-based leadership teams at both sites—composed of students, parents, teachers, and community members, as well as the principal and coordinator—prioritized addressing the issue during the 2023–24 school year. Following dedicated programming for students on life skills and the impacts of substance use, information presented to parents about how to identify vapes, partnerships with community-based organizations like La Casa to talk about addiction and help address root causes of students’ decisions to use, and improvements in adult–student relationships, both schools have seen dramatic decreases in substance use infractions.

Community School Partners at Sierra Middle School and University High School

Sierra Middle School and University High School both partner with a number of community-based organizations, nonprofits, and businesses for programming and supports. Community school partners include:

- Boys Leadership/Girls Circle With Casakids. This social-emotional learning program is held during the school day and promotes positive peer relationships. The programming allows students to share their home life issues and collaborate on solving problems.

- Community Members. University High partners with a local accountant to teach students, particularly juniors and seniors with full-time jobs, how to file taxes. Sierra partners with providers for adult education classes such as GED test preparation, computer skills, and workforce development.

- Emerge. A new partner, Emerge helps students to prepare for living independently and develop life skills (e.g., resume building, filing taxes, applying for public benefits, etc.).

- La Casa Behavioral Health. Among other things, this partner provides emergency mental health appointments for students and educators. It also leads a substance abuse group for students and provides physical health services for Roswell families.

- Wings for L.I.F.E. This social-emotional learning program is provided by a community-based organization of the same name and focuses on positive youth development.

Sources: Interviews, observations, and document review at both schools by Learning Policy Institute. (2024).

Key Accomplishments

School transformation takes time, and achieving full implementation of the community schools strategy is no different. Although the four community schools in Roswell are still in the process of fully implementing their vision, they have seen significant progress in some areas. Sierra and University High, in particular, have seen improvements related to school climate and culture, as well as other areas, including graduation rate and staff retention (see Progress at Sierra Middle School and University High School). The community schools strategy has made an important contribution to this progress.

Progress at Sierra Middle School and University High School

University High School

- The number of student fights dramatically decreased. As of April 2024, there had been only one student fight at University High during the entire 2023–24 school year. In previous years, there were typically more than 10 fights per semester.

- The number of suspensions substantially decreased. Suspensions at University High dropped 78% from the 2022–23 school year (274 suspensions) to the 2023–24 school year (61 suspensions).

- The graduation rate grew by nearly 20 percentage points. The 4-year graduation rate at University High increased from 36% in 2022 to 55% in 2023, which was maintained in 2024.

Sierra Middle School

- More students reported that they had a caring adult in their life. The number of students who reported that they had a caring adult in their life who regularly checks on them improved from 4% to 31% over the course of 3 years (2019–2022). While there is still room for improvement, this growth is especially impressive during a global pandemic and school closures.

- Staff retention rates increased. Of a school staff of 60 individuals, 3 teachers retired after the 2023–24 school year—cutting the attrition rate nearly in half from the average of the prior 2 school years.

Both Schools

- The number of substance abuse infractions substantially dropped. In the 2022–23 school year, substance abuse infractions declined by 80% at University High to only four instances by April 2024 and were on track to decrease by 80% at Sierra as well (there were only six instances as of the first semester in the 2023–24 school year). This was a major goal at both community school sites.

Sources: Interviews with school and district officials by Learning Policy Institute. See also: Bryant, J. (2024, April 11). Why educators at this ‘failing’ high school believe it can be turned around. The Progressive.

Conclusion

Although Sierra Middle School and University High School are at different stages of community school implementation, both schools have made progress in the journey of transforming into fully implemented community schools and have seen encouraging improvements in school climate and culture. The collaborative leadership opportunities at both sites—including the important role of the student senate at University High and the student leadership in designing Sierra’s after-school program—have played an important role. Roswell’s district-level investment and support are also contributing to this progress, and the district plans to expand the strategy to additional schools. One factor that will strongly impact continued progress in Roswell is the availability and consistency of community schools funding. For example, reduced grant funding in the 2024 award cycle means that school and district staff have had to cut personnel—including the school therapist—and prepare for possible reductions in programming (e.g., after-school activities). Despite this obstacle, Roswell’s community schools work has begun to transform students and families’ relationships and engagement with school for the better.

New Mexico Community School Profile: Roswell Independent School District (brief) by Daniel Espinosa is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This work was supported by the ABC Community School Partnership. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the author and not those of our funders.