Redesigning High School: 10 Features for Success

Summary

It is increasingly clear that the factory-model secondary schools we inherited from a century ago are not designed to educate the next generation to face today’s challenges. Many educators are seeking to develop new models, recognizing that the assembly line structure of these schools was not designed for the strong relationships, deeper learning opportunities, and equitable outcomes we need today. This brief provides an overview of 10 evidence-based features of effective redesigned high schools, aligned with the guiding principles of the science of learning and development (SoLD): (1) positive developmental relationships; (2) safe, inclusive school climate; (3) culturally responsive and sustaining teaching; (4) deeper learning curriculum; (5) student-centered pedagogy; (6) authentic assessment; (7) well-prepared and well-supported teachers; (8) authentic family engagement; (9) community connections and integrated student supports; and (10) shared decision-making and leadership.

The report on which this brief is based can be found at https://www.redesigninghighschool.org.

Supporting Learning and Development

In recent years, our understanding of the science of learning and development (SoLD) has deepened considerably, allowing us to better design schools to support student learning.Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2019). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science, 23(4), 307–337. This is particularly important in high schools, which were designed to mimic the factory-model assembly line that was popular a century ago. The structure was meant to ensure efficiency by moving young people from one teacher to the next, in 45-minute increments, to be stamped with separate, disconnected lessons 7 or 8 times per day, with a hallway locker as their only stable point of contact. New high school designs supporting greater success are now emerging. Research shows that they share 10 evidence-based features that offer a blueprint for high school transformation.

Feature 1: Positive Developmental Relationships

What Students Need

A high-quality education starts with relationships. Neuroscientists have shown that emotions and cognition are closely linked, with positive relationships and stimulating experiences creating the neural connections that allow young people to develop their attention, focus, memory, and other processes essential to learning. Yet traditional secondary school structures—which move students from one teacher to the next and assign more than 100 students to each teacher—often prevent teachers from getting to know each student well. This becomes even more difficult when teachers work in isolation from one another, with little time to plan together or share their knowledge about what students need. Even when teachers care deeply about their students, it is not possible in this structure for the teachers to care effectively for all their students’ needs. Effective schools create structures that support positive developmental relationships between adults and young people, as well as among young people themselves.

Key Practices

Schools designed to encourage positive, developmental relationships develop structures that allow students to be well known, including:

- Small Learning Communities. Whether small schools or smaller units within large schools, small learning communities tend to produce significantly better results for students, including better attendance, more participation in extracurricular activities, stronger academic achievement, fewer behavioral incidents, lower dropout rates, and higher graduation rates.Darling-Hammond, L., Ross, P., & Milliken, M. (2006). High school size, organization, and content: What matters for student success? [Brookings Papers on Education Policy]. Brookings Institution Press. Large schools may use “houses” or “academies,” cohorts of students and teachers (usually 300–400 students) that form unique identities and intentional community. In addition, teaching teams that share a group of students can personalize instruction for those students by planning around their needs and interests and, sometimes, following the students from one grade to the next.

- Student-Centered Staffing Models. Structures like block scheduling and looping allow schools to redesign the use of staff and time to provide reduced pupil loads and greater continuity, allowing teachers to get to know their students better.

- Advisory Systems. Advisory systems support student success by assigning groups of 15–20 students to meet with a faculty advisor several times per week to receive ongoing academic and social-emotional support. Successful advisories provide a structured space for checking in on home and school conditions, building community, exploring college and career opportunities, and teaching strategies such as conflict resolution. They also provide a primary adult point of contact, who connects closely with parents and acts as an advocate for students.

Feature 2: Safe, Inclusive School Climate

What Students Need

Strong positive relationships between educators and students are necessary but not sufficient to ensure that students succeed in school. To unleash students’ full learning potential, schools must provide them with an environment that is physically and psychologically safe, calm, and consistent. Brain research helps explain why this type of environment matters so much. When we are in an environment that feels unpredictable or threatening, our brains are flooded with cortisol, which increases stress levels, reduces the capacity for memory and focus, and impairs concentration. Moreover, this reaction is heightened if we have experienced toxic stress over time, making it even more difficult for our brains to concentrate on learning. When we are in a calm, trusted environment, we can concentrate and learn more easily.

Key Practices

To enable all students to learn, effective schools are places where everyone feels safe and included. Such schools emphasize the following:

- Community Building. In effective schools, expectations for student behavior are framed around shared values, which are rooted in the right of every student to feel safe and be included, rather than long lists of rules and punishments. These values, which focus on respect and consideration for others, are developed and discussed in concert with students, who become advocates for the norms and for one another. Strategies like community circles, in which students regularly share their experiences and thoughts with one another, create community bonds that form and maintain relationships that protect a positive school climate.

- Social and Emotional Learning. Explicitly teaching social, emotional, and cognitive skills helps demystify the growth process for young people and allows them to cultivate agency in their personal development. Social and emotional learning can be developed through practices such as helping young people become aware of their own and others’ feelings and perspectives, develop empathy, learn skills of collaboration and conflict resolution, and adopt a growth mindset. Other strategies include implementing mindfulness practices that teach students how to develop a greater sense of awareness and adopting trauma-informed and healing-oriented practicesOffice of the California Surgeon General. Safe spaces: Foundations of trauma-informed practice for educational and care settings. that address the impact of trauma with supportive relationships and counseling while promoting individual and collective wellness.

- Restorative Practices. The cornerstones of a safe, inclusive school climate include a set of social- emotional skills for recognizing emotions, collaborating with others, and resolving conflict peaceably. Educators in healthy school communities understand that conflict is normal, and they prepare for it by establishing productive processes for managing disagreements, followed by training and supporting staff and students to consistently apply these approaches to resolve disputes, rather than excluding students through suspensions. In restorative schools, the goal is to support students daily through community building, explicit teaching of problem-solving and empathy, and methods that repair harm and enable students to make amends.Gregory, A., Clawson, K., Davis, A., & Gerewitz, J. (2016). The promise of restorative practices to transform teacher–student relationships and achieve equity in school discipline. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 26(4), 325–353; Losen, D. J. (2015). Closing the discipline gap: Equitable remedies for excessive exclusion. Teachers College Press. A recent large-scale study found that the more students engage with such practices, the more their academic achievement and mental health improve, the better the school climate, and the less violence and misbehavior occur in schools.Darling-Hammond, S. (2023). Fostering belonging, transforming schools: The impact of restorative practices. Learning Policy Institute.

Feature 3: Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Teaching

What Students Need

An important part of creating an educational community where young people can thrive and learn is ensuring that all students feel valued and seen for who they are. Redesigning schools involves an explicit commitment to culturally responsive and sustaining teaching, which promotes respect for diversity and allows all students’ experiences to be understood, appreciated, and connected to the curriculum. Every student has cultural experiences shaped by their family, friends, neighborhood, interests, language background, religion, and other aspects of their lives. Effective educators proactively create a school environment that explicitly embraces the identities and cultures represented in their classrooms as well as in the larger society.

Key Practices

Learning is a process of drawing connections between what we know and what we are discovering, so having an understanding of students’ cultural contexts provides the foundation for learning and identity development. A growing body of research shows how educators can foster identity-safe environments that counteract societal stereotypes. Practices include:

- Teaching and Practicing Empathy and Social Skills. Practices that build empathy and common ground among students and teachers reduce bias and support the growth of positive and trusting relationships. Teaching that promotes student responsibility for and engagement in the classroom community supports belonging. Community circles and empathy interviews, increasingly used in secondary settings, are guided interactions that can be used by teachers and students to better understand challenging situations or to offer insights into an individual’s lived experience.

- Understanding and Connecting to Cultural Contexts. Culturally responsive and sustaining practices require teachers to learn what students already know, the areas in which they already demonstrate competence, and how that knowledge can be leveraged for deeper learning in the classroom context. The most effective aspect of this practice is to provide learning spaces, materials, and tasks that not only are relevant and responsive to students’ cultures, languages, experiences, and identities but also center them in ways that affirm students’ competence and sustain students’ cultural ways of knowing and being.

- Gaining Knowledge of the Community. Effective schools are connected to the culture and resources of the communities where they are situated. Their curriculum and projects draw on community resources and often address community needs. Faculty have explicit opportunities to learn about the community from parents and community members. Schools also draw on community members and organizations, hosting clubs and activities that draw on the assets and cultural contexts of the community.

Feature 4: Deeper Learning Curriculum

What Students Need

Schools that motivate and succeed with learners from diverse backgrounds support intellectually challenging work and focus on preparing all students to meet the higher-order thinking and problem-solving skills demanded by contemporary college and careers. The most powerful mode of learning for human beings is generated by meaningful inquiry that awakens the brain to search for answers.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. National Academies Press. This enables deeper learning that allows students to make meaning of information and the world in which they live so that, ultimately, they can use knowledge for their own purposes.

Key Practices

Although factory-model schools were designed to cover curriculum in a standardized manner, often as a set of disconnected facts that are not deeply explored, we know from research in the learning sciences that students learn by understanding how ideas fit together. They also learn at different paces and in different ways that build on their prior experiences and connect to their interests, modes of processing and expression, and cultural contexts. A deeper learning curriculum focuses not only on content expertise but also on other essential competencies, including critical thinking, effective communication, collaboration, and self-directed learning. Practices include:

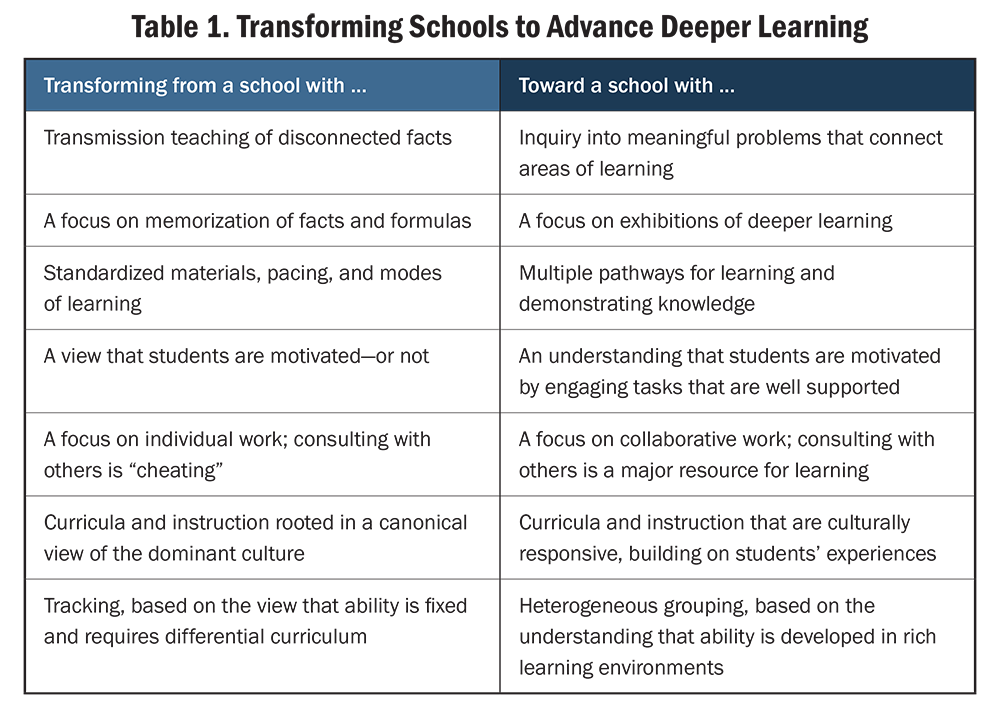

- Learning Through Inquiry. Deeper learning is supported by inquiry that engages students in answering essential questions that challenge students to understand concepts deeply, find and integrate information, assemble evidence, weigh ideas, and develop skills of analysis and expression. Often sustained inquiry is structured as project-based learning that explores real-world issues through questions students pursue, resulting in a product presented to an authentic audience, including written documentation and often an oral presentation, exhibition, or portfolio defense. (See Table 1.)

- Community Service Activities and Internships. Having opportunities to pursue community service and internships allows students to explore their interests and future career goals, contribute to the lives of others, and learn how to engage the world outside of home and school. This real-world work, often accompanied by seminars and reflective assignments, offers an authentic curricular experience.

Feature 5: Student-Centered Pedagogy

What Students Need

Just as an effective secondary school curriculum must take into account the needs and interests of students, teachers’ instructional practices must also be personalized and student-centered. Traditional secondary schools often assume that the only way to support students who have different needs or skill levels is to separate them into different tracks where they are taught different material. This approach usually results in students from historically marginalized groups receiving a lower-quality curriculum from less experienced teachers in a pathway that predetermines learning opportunities for many years.Oakes, J. (2005). Keeping track: How schools structure inequality (2nd ed.). Yale University Press. A student-centered pedagogy recognizes that each student is a unique individual who learns in their own way and can thrive when teaching offers multiple pathways for learning.

Key Practices

Effective schools reduce tracking, provide challenging and engaging coursework to everyone, and adjust teaching modes to meet students’ needs. Adaptive teaching can be facilitated through the following practices:

- Universal Design for Learning. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework for designing a learning environment in which all students can access meaningful learning. By providing multiple paths of engagement and representation, schools can ensure that students understand new information and generate new understandings that they can communicate in different ways.

- Scaffolding. Student-centered teachers provide scaffolding for student tasks, attending to different skill levels or modes of learning. Instead of simply assigning students to write a research paper, for example, teachers may lead students through a step-by-step process with a range of supports that help them develop a high-quality finished product. Or they may scaffold through structured group work, in which expertise is distributed among group members.

- Feedback and Revision. Student-centered teachers provide opportunities for mastery by structuring work so that students can tackle difficult tasks by iterating toward excellence with continual opportunities for feedback, practice, and revision guided by rubrics that make learning goals clear. This supports students in developing the courage and confidence to work continuously so they improve in their successive efforts.

- High-Quality, High-Intensity Tutoring. One of the most useful equity-enhancing interventions is high-quality, high-intensity tutoring. Studies have shown that when implemented effectively, high-intensity tutoring can produce significant gains in student skill levels by teaching students exactly where they are and enabling them to advance rapidly in a matter of weeks rather than years. Successful secondary schools often allocate time for tutoring through support periods available to all students or lab classes attached to specific courses; after-school tutoring sessions; Saturday school options; or online tutoring from trained volunteers, educators, or more advanced students.

Feature 6: Authentic Assessment

What Students Need

In addition to rethinking curriculum and pedagogy, redesigned schools take more meaningful approaches to assessment that begin with clarity about what students should know and be able to do when they graduate and continue by creating opportunities for students to develop, refine, and exhibit those skills in authentic ways. Performance assessments allow students to demonstrate their knowledge more fully by directly exhibiting a skill, reporting on an investigation, developing a product, or performing an activity. Research shows that students who regularly engage in such assessments do as well on traditional standardized tests and better on tests of analytic and performance ability than other similar students. They are also better prepared for college and the workplace. Teachers who regularly use and score such assessments learn more about how their students understand the material and demonstrate applied skills, as well as how their work reflects the standards embedded in the assessments.

Key Practices

By measuring students’ abilities to apply knowledge to solve pertinent problems, performance assessments encourage and support more rigorous and relevant teaching and learning. Instituting performance assessments necessitates the following practices:

- Clear and Meaningful Expectations. Over the past 2 decades, an increasing number of schools, districts, and states have adopted what is known as a Graduate Profile, which reflects the knowledge and skills students need to be ready for college and career. These standards often include ambitious academic goals, critical-thinking skills, communication skills, skills in new technologies, cultural competence and multilingualism, emotional intelligence, and leadership skills. With these goals in mind, the school’s faculty then determine in more detail what is essential for their students to know and be able to do and how they can demonstrate those skills in meaningful ways.

- Performance Assessment Systems. These assessment systems are based on common, schoolwide standards reflected in projects that are integrated into daily classroom practices that use models, demonstrations, and exhibitions to show students the kind of work they will be expected to produce. Such assessment systems include, for example, portfolios of student work that demonstrate in-depth study through research papers, scientific experiments, mathematical models, literary critiques, and arts performances; rubrics that embody the set of standards against which students’ products and performance are judged; oral presentations by students to a committee of teachers, peers, and others in the school to assess each student’s in-depth understanding and readiness for graduation; and opportunities for students to improve their work so they can demonstrate what they have learned.

- School Supports. These systems produce data about what students know and can do that can drive ongoing improvements in curriculum and teaching. Having school supports in place ensures that the data gathered through an effective performance assessment system will help teachers improve their practices. For example, joint curricular planning among teachers is needed for curriculum and assessment to “add up” to these expectations throughout the school—that is, to build ideas and skills from one course to another and from one year to the next. Structuring extended learning time for students—in lab courses, in a resource room, and beyond traditional school hours—so that they can continue to refine their work and understandings is another important way to enable all students to succeed.

Feature 7: Well-Prepared and Well-Supported Teachers

What Students Need

A substantial body of research suggests that one of the most important determinants of student achievement in schools is the quality of teachers. Redesigned high schools invest deeply in training, involve teachers in decision-making, and provide teachers with scheduled time and opportunities to create a coherent set of practices and become experts at their craft. Teachers with these opportunities are more effective and more likely to remain in a school for the long run, resulting in improved student achievement.Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Learning Policy Institute.

Key Practices

For teachers to ensure success for students who learn in different ways and encounter a variety of challenges, they must be prepared as diagnosticians, planners, and leaders who know a great deal about the learning process and have a wide repertoire of tools at their disposal. This means that schools closely attend to:

- Teacher Preparation. Effective schools and districts do not leave teacher hiring to chance. They devote resources and attention to recruiting well-trained educators, often by establishing professional development school partnerships with local teacher education programs. Teachers who enter their careers with comprehensive preparation are half as likely to leave teaching after the first year as those who enter without preparation.Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Diversifying the teaching profession: How to recruit and retain teachers of color. Learning Policy Institute. Grow Your Own programs, including paraprofessional pathways and teacher residencies, can support community members in becoming effective teachers and provide opportunities for seamless support for new educators.

- Time for Teacher Collaboration. Expertise in teaching—as in many other fields—comes from a process of sharing, innovating, reflecting on practices, and developing new approaches. Good teachers continuously learn with and from one another, and they need time to do so. Redesigned schools build in significant time during the school day for collaborative work, which includes developing curricula and assessments, observing colleagues’ classes, and participating in other professional development activities. As part of collaborative decision-making, staff frequently revisit the school’s vision and goals, assess needs, and make changes in their collective practices to enable continuous improvement.

- Strategies for Teacher Learning. Collaboration time can be used for not only planning but also peer-supported learning that engages teachers in active colearning, supported by modeling and coaching with feedback and reflection opportunities. Examples of collective learning include teacher action research, in which educators engage in systematic and rigorous inquiry about a question of practice, involving cycles of planning, acting, observing results, and reflection; reciprocal peer observations, in which teachers schedule time to observe one another’s lessons and provide structured feedback; and lesson study, which allows teachers to collaborate on lesson planning and implement lessons first with each other and then in the classroom while other teachers observe and offer feedback.

Feature 8: Authentic Family Engagement

What Students Need

Educators’ most important partners, besides the students themselves, are the students’ families and caregivers. Family engagement is a priority in many elementary schools, but sustaining it is challenging in most traditional secondary schools when there are few opportunities for teachers and families to meet or talk regularly. Yet adolescence is a critical time in brain development and social and emotional growth—a time when it is more important than ever for educators and caregivers to be on the same page. Research shows that authentic family engagement can improve attendance rates, create a more positive school climate, and increase academic achievement.Henderson, A., & Mapp, K. (2002). A new wave of evidence: The impact of school, family, and community connections on student achievement. Annual synthesis. National Center for Family & Community Connections with Schools, Southwest Educational Development Laboratory. Just as strong teacher–student relationships provide invaluable support to students, solid partnerships between teachers and families are also a key component of student success.

Key Practices

Secondary schools that have been redesigned to foster connections among educators, students, and families enable teachers to better support young people and tailor their teaching to individual needs. Key practices for authentic family engagement include the following:

- Communication With Families. Advisory systems are key to regular family communication in secondary schools. Advisors take responsibility for being in touch with the families of the 15–20 students they support, making visits and positive phone calls home; hosting student-led parent–teacher conferences several times per year; and being a point of contact for other teachers so they can communicate needs to parents as well as other educators. Effective schools prioritize regular, positive communication with families by setting aside time for the visits and conferences required, thereby building trust and making families feel welcome.

- Home Visits. Planned home visits are a research-based approach to building positive teacher–parent relationships at the secondary level. These visits by advisors to their advisees’ families not only build trust and engage families but also help teachers understand parents’ goals for their children and offer valuable learning experiences for teachers who may not come from the same communities as their students. Home visits are seen as the start of a relationship rather than a one-time event.

- Family Involvement. Authentic partnerships with parents and guardians—in which educators tap into the parents’ and guardians’ expertise—can lead to mutually supportive practices at home and school. Beyond strong relationships with advisors, strategies to involve families include student-led parent–teacher conferences; academic exhibitions; and family services, such as family literacy or continuing education programs. Flexibility is essential for connecting with all caregivers and can mean offering meetings at flexible times and in various formats, providing parents with food and childcare, and utilizing multiple means of communication, including staff who speak parents’ native languages, so parents feel respected and welcomed in the community.

Feature 9: Community Connections and Integrated Student Supports

What Students Need

Schools cannot educate students effectively without addressing their basic needs, such as access to stable housing, healthy food, mental and physical health services, and the technology required for 21st-century learning. One important way to address these needs is to partner with community organizations. With trusting relationships and coordinated support, schools can ensure that students receive the health, social services, and learning opportunities they need to succeed. Evidence shows that such supports can lead to improvements in students’ attendance, academic achievement, and high school graduation rates while also reducing racial and economic achievement gaps.Maier, A., Daniel, J., Oakes, J., & Lam, L. (2017). Community schools as an effective school improvement strategy: A review of the evidence. Learning Policy Institute.

Key Practices

For a school to work with the community, its staff must know the community it serves—its multiple cultures, youth organizations, and other strengths that exist that could be assets for the school. Practices to support community connections include the following:

- Knowledge of the Community. Schools can become places where a community can celebrate its strengths, both through cultural programs and partnerships with local community initiatives. Educators who come from the community are well positioned to foster these connections, and students’ parents or family members can also serve as vital bridge-builders in this effort. Educators from other communities or backgrounds should approach this work with a mindset of listening, learning, and humility.

- Community Schools. The Community Schools Framework guides the development of schools that serve as community hubs and partner with community organizations to educate the whole child. Each school designs its program to meet the specific needs of its students and their families, using the community’s assets as a starting point. Although they differ in specific approaches, community schools are guided by common pillars: integrated student supports; family and community engagement; collaborative leadership and practices; expanded learning time and opportunities; a culture of belonging, safety, and care; and rigorous, community-connected classroom instruction. By using these pillars, which are closely aligned with the 10 features for high school redesign success, community school designs enhance efforts to create relationship-centered schools that support deeper learning with connections to community organizations.

Feature 10: Shared Decision-Making and Leadership

What Students Need

Students need a coherent, supportive environment in order to feel safe and to learn optimally with shared expectations across classrooms. To offer that reliable, safe environment, the elements of a school’s design require the buy-in of the entire school community, including staff, students, and family members who understand and support the community’s vision. Achieving this goal requires shared decision-making and leadership in the school’s design, implementation, and continuous learning. Research indicates that teacher participation in school decision-making is associated with greater retention of teachers and improved academic achievement for students.Hallinger, P., & Heck, R. H. (2010). Collaborative leadership and school improvement: Understanding the impact on school capacity and student learning. School Leadership and Management, 30(2), 95–110.

Key Practices

Key elements of a collaborative community that employs shared decision-making and leadership include:

- Shared Norms and Values. Shared norms and values, when enacted in the context of collaborative decision-making, are the foundation for relational trust, which studies have found is essential for school improvement. Working through these values is worth the time it takes to develop a strong consensus about the goals for student learning and what joint work will be undertaken. Successful schools have faculty, student, and parent leaders who participate in school governance through setting school norms and participating in hiring and other tasks.

- Agency and Voice. Through academic standards and shared values, well-structured schools place daily decision-making authority as close as possible to the classroom by giving teaching teams the responsibility for making decisions and then holding them accountable for student performance. Effective schools also cultivate meaningful student voice and leadership by providing them leadership opportunities, input into curricular design, and voice at regular community meetings.

Over the past 3 decades, thousands of secondary schools have demonstrated that it is possible to support learners to meet high levels of success, including those students who have been historically marginalized. The goal is to expand these opportunities by creating the conditions for transformation of students’ experiences and by redesigning systems at the district, state, and federal levels to enable a new architecture for education that enables even more students to thrive.

Redesigning High School: 10 Features for Success (brief) by Linda Darling-Hammond, Matt Alexander, and Laura E. Hernández, with Cheryl Jones-Walker is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.

Cover photo by Allison Shelley/The Verbatim Agency for EDUimages.