Summary

Through its redesign journey, Fremont High School has gone from a school where families did not want to send their children to an award-winning school with a waiting list for admission. Community organizing efforts created a strong foundation of relationships between staff and families from which to build. District- and state-level funding toward community schools, Linked Learning, and dual enrollment built on that foundation to create a learning environment at Fremont in which students experience relationships of deep care and meaningful instruction that prepare them for both college and career. This brief tells the story of Fremont’s journey from an isolated campus with severe underenrollment to a vibrant community school where students have access to authentic, community-connected learning and families hold power on campus.

Fremont’s Journey From Reform Fatigue to Redesign

Families have not always wanted to send their children to Fremont. In the late 1990s, the school faced steep underenrollment and students largely felt unsafe on campus. Over the past 25 years, the school has gone through three major reform efforts. In the early 2000s, the small schools movement in Oakland Unified School District (Oakland Unified)—led by Oakland Community Organization—called attention to inequities between schools in the Oakland hills and those in the “flatlands,” where Fremont is located, and energized students and families to reinvest in their local public schools. This movement helped open new, intimate campuses and create small schools within larger campuses that could provide students with the trusting, supportive environment required to learn.The Gates Foundation provided funding for this effort. Gates Foundation. (n.d.). $9.5 million grant builds on success in transforming Oakland’s high schools. Although these small schools were found to be more effective for students, state budget cuts caused the district to close and reconsolidate many of them, including at Fremont.

In late 2014, in a bid to revive performance at Oakland Unified’s lowest-performing schools, Fremont staff learned that the district would be accepting proposals—including those from outsiders—to redesign the school. Fremont staff held both formal and informal meetings with students, families, and members of the community to draft a proposal of their own. They also solicited input from feeder middle and elementary school students and families.Fremont High School. (2015). Quality school development proposal.

Their proposal built on their emerging community schools approach and set a high bar. They proposed advisories that would allow students to be known well by staff, rigorous project-based learning, teaching teams to provide individualized attention, and small learning communities—similar to the prior small schools movement—in industry-themed pathways.Fremont High School. (2015). Quality school development proposal. They proposed that the school community choose its own principal, someone who would be committed to staying at the school for at least 5 years. “We wanted a community school that would be a beacon in this part of East Oakland,” said Jasmene Miranda, Fremont alumna and director of the school’s Media Pathway.Community Concern Films. (2025). Rooted in Oakland.

What Is a Redesigned School?

Much of what the Fremont community did to redesign their school reflects the features outlined in Redesigning High School: 10 Features for Success. Redesigning schools requires a shift in mindset related to school structures, practices, and instructional approaches that allow schools to provide instructional experiences rooted in how students learn best. The 10 features are:

- Positive developmental relationships

- Safe, inclusive school climate

- Culturally responsive and sustaining teaching

- Deeper learning curriculum

- Student-centered pedagogy

- Authentic assessment

- Well-prepared and well-supported teachers

- Authentic family engagement

- Community connections and integrated student supports

- Shared decision-making and leadership

In tandem, these features create learning environments in which students are cared for, challenged, and supported. Students coconstruct learning alongside educators, family members, and the whole community while developing an array of social, emotional, and academic skills that support them for the world ahead. Redesigned schools are structured to integrate all 10 features over time and recognize how the 10 features bolster one another.

Source: Darling-Hammond, L., Alexander, M., & Hernández, L. (2024). Redesigning high school: 10 features for success. Learning Policy Institute.

Relationship-Centered Design Focused on Purposeful Learning

In fall 2016, the staff opened their redesigned school. Nearly 10 years later, and after significant district- and state-level investments in community schools and college- and career-focused learning, Fremont’s students are thriving. The school serves 1,166 students in Oakland Unified. A majority of its students (77%) identify as Hispanic or Latino/a; 13% identify as African American, the school’s second largest demographic group.California Department of Education. (2025). 2024–25 enrollment by ethnicity and grade [Fremont High Report 01-61259-0125716]. DataQuest. (accessed 08/11/2025). Fifty-three percent of students are classified as English learners, 16% are students experiencing homelessness, 13% are students with disabilities, and 99% are identified as socioeconomically disadvantaged.California Department of Education. (2025). 2024–25 enrollment by subgroup [Fremont High Report 01-61259-0125716]. DataQuest. (accessed 08/11/2025). The four small communities in which Fremont’s students learn are:

- 9th-Grade House. Students and teachers work together as a tight-knit community. Advisors support the freshman transition to high school, including helping students choose their 10th- to 12th-grade pathway. Ninth-grade teachers meet weekly to discuss the best strategies and methods for supporting each student.

- Architecture Pathway. Educators infuse coursework with the principles of design and develop transferable skills through career experiences in the field of architecture. Using technology and cross-curricular learning around academy themes, students produce research, projects, and presentations that are relevant and responsive to the needs of their community. Students complete the A–G courses required for college admission in California, connecting to their Linked Learning pathway theme (a sequence of industry-themed courses that prepare students for college and career), along with career technical education courses, job shadowing, and internships.

- Media Pathway. Students are immersed in a creative community that utilizes technology to communicate through multiple forms of media, including journalism, photography, film, design, and virtual reality. As in the Architecture Pathway, students are immersed in project- and problem-based learning, complete A–G courses aligned to their Media Pathway theme, and have access to career-focused learning experiences.

- Newcomer Educational Support and Transition (NEST) Program. This program provides newly arrived adolescent immigrants—who compose about one fourth of the school’s population—with a rigorous and accessible curriculum focused on 21st-century skills, social-emotional learning, and preparation for college and career. Students have access to the A–G college-preparatory curriculum and to technical education as they learn English, develop a sense of belonging, and access the services they need.

Since the community-led redesign in 2015, the school’s outcomes have greatly improved. Fremont has increased graduation rates (from 60% in 2016–17 to 81% in 2023–24) and the number of students completing A–G courses (from 27% in 2016–17 to 60% in 2023–24).California Department of Education. (2025). 2016–17 four-year adjusted cohort graduation rate [Fremont High Report 01-61259-0125716]. DataQuest. (accessed 08/11/2025); California Department of Education. (2025). 2023–24 four-year adjusted cohort graduation rate [Fremont High Report 01-61259-0125716]. DataQuest. (accessed 08/11/2025). During the same time, suspension rates have decreased from 15% to 8%, and enrollment has increased (from 764 in 2016–17 to 1,166 in 2024–25).California Department of Education. (2025). 2023–24 suspension rate [Fremont High Report 01-61259-0125716]. DataQuest. (accessed 08/11/2025); California Department of Education. (2025). Enrollment multi-year summary by ethnicity [Fremont High Report 01-61259-0125716]. DataQuest. (accessed 08/11/2025).

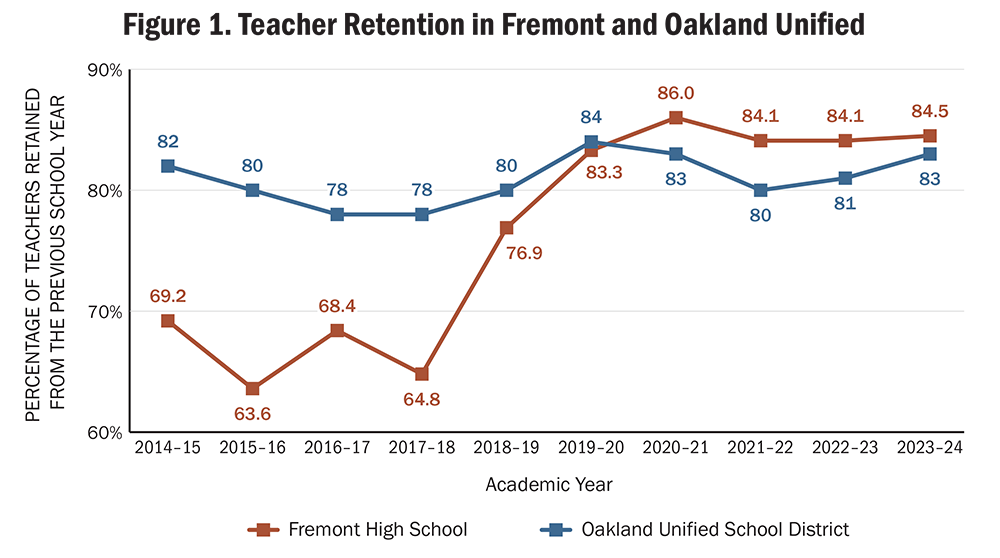

Students can earn college credit through dual enrollment courses and complete industry-themed Linked Learning pathways that prepare all students for college and/or lucrative careers. Despite teacher shortages in the state and district, Fremont has dramatically increased its teacher retention rates over the past 10 years and now retains teachers at a higher rate than the district average (See Figure 1).Hong, J. (2022, March 17). Short-term fixes won’t really solve California’s teacher shortage. CalMatters; Lu, X. (2023, July 25). With school 2 weeks away, OUSD still needs about 100 teachers. The Oaklandside; Oakland Unified School District. (2025). Retention of teachers at school sites, teacher retention at sites over time—Fremont High School. [Dataset]. (accessed 08/11/2025); Oakland Unified School District. (2025). Retention of teachers in OUSD. [Dataset]. (accessed 08/11/2025).

State Policies That Support School Success

Several major state initiatives, building on local investments, contributed to the turnaround in student outcomes:

- The California Community Schools Partnership Program has invested $4.1 billion since 2021 in developing community schools that support family and community engagement, integrated supports for students, expanded learning time, and shared decision-making in settings that support social and emotional learning and restorative practices.Swain, W., Leung-Gagné, M., Maier, A., & Rubinstein, C. (2025). Community schools impact on student outcomes: Evidence from California. Learning Policy Institute.

- The Golden State Pathways Program, established in 2022, invested $500 million in industry-themed pathways that offer integrated coursework and internships that can provide both high school and college credit.

- Investments in dual enrollment learning opportunities statewide, including an additional $200 million in 2022, support high schools and community colleges in establishing opportunities for high school students to take credit-bearing college courses during the school day.

These investments will continue in California. In 2025, the governor issued a Career Master Plan that creates a vision for integrating initiatives across the education, labor, and higher education sectors and moves toward the recognition of competencies through a Career Passport. In the 2025–26 budget, the state invested $10 million in a pilot program to support high school redesign, which will continue to shape learning for both schools and state policymakers as it identifies opportunities for further innovations in policy and practice.

Over time and with targeted investments, Fremont has changed its reputation. It now has a waiting list of several hundred families, when it was previously underenrolled by nearly as many. Most important, as Principal Nidya Baez—a Fremont alumna who was part of the initial redesign team—repeatedly points out, the conversation at Fremont has moved beyond basic safety and toward academic excellence, which is what she always dreamed it would be.

Enabling Conditions for School Transformation

Four districtwide initiatives—community schools, Linked Learning, dual enrollment, and performance assessments through the graduate capstone—have played essential roles in Fremont’s redesign. Community schools provide students and families with resources and structures that support them in thriving.Community Schools Forward. (2023). Framework: Essentials for community school transformation. Industry-themed Linked Learning pathways allow students to experience high-quality, authentic, and coherent learning experiences anchored in in-demand careers in fields like architecture and media.The James Irvine Foundation provided the initial funding for the development of Linked Learning pathways in Oakland Unified beginning in 2006. Guha, R., Adelman, N., Arshan, N., Bland, J., Caspary, K., Padilla, C., Patel, D., Tse, V., Black, A., & Biscocho, F. (2014). Taking stock of the California Linked Learning district initiative. SRI International. Pathways include dual enrollment courses in which students can earn college credit during the school day. The district’s graduate capstone initiative, in which seniors complete a yearlong sustained research project, provides a North Star for high-quality project- and problem-based learning.Maier, A., Adams, J., Burns, D., Kaul, M., Saunders, M., & Thompson, C. (2020). Using performance assessments to support student learning: How district initiatives can make a difference [Brief]. Learning Policy Institute; Oakland Unified School District Board of Education. (2005). BP 6146.1 High school graduation requirements. Oakland Unified School District. Community schools, Linked Learning, dual enrollment, and performance assessments allow educators to create meaningful, community-connected learning experiences. Combined, they have helped upend the traditional factory model of schooling.

What Is a Community School?

Community schools are an evidence-based school transformation strategy that unites the efforts of students, families, educators, and community partners to improve student learning and well-being. They leverage a complex web of partnerships and relationships, like those at Fremont High School in Oakland, to support and engage students and families and provide a framework for engagement and shared decision-making. These partnerships and relationships—and the resources that they can bring to bear—can nurture authentic, rigorous, community-connected learning experiences and create the conditions for young people to thrive.

Community schools typically have a community school manager (sometimes called a community school coordinator or director). This individual is often part of the school leadership team and is responsible for coordinating partnerships and leveraging school and community-based resources to support and engage students and families in accessing health and mental health services, social services, expanded learning and recreational opportunities, and connections to many community organizations. Community schools are grounded in an evidence base showing improvement in student outcomes, including attendance, academic achievement, and high school graduation rates, along with reduced racial and economic achievement gaps. Community schools are also associated with some improvements in school climate and disciplinary rates.

Sources: Community Schools Forward. (2023). Framework: Essentials for community school transformation; Klevan, S., Daniel, J., Fehrer, K., & Maier, A. (2023). Creating the conditions for children to learn: Oakland’s districtwide community schools initiative. Learning Policy Institute; Johnston, W. R., Engberg, J., Opper, I. M., Sontag-Padilla, S., & Xenakis, L. (2020). Illustrating the promise of community schools: An assessment of the impact of the New York City Community Schools Initiative. RAND Corporation; Maier, A., Daniel, J., Oakes, J., & Lam, L. (2017). Community schools as an effective school improvement strategy: A review of the evidence. Learning Policy Institute; Partnership for the Future of Learning. (2018). Community schools playbook. Learning Policy Institute; Swain, W., Leung-Gagné, M., Maier, A., & Rubinstein, C. (2025). Community schools impact on student outcomes: Evidence from California. Learning Policy Institute.

Community Schools as a Foundation. Fremont’s community school transformation began in spring 2012, the same year that it reconstituted from three small schools back into a single, large comprehensive high school.Fehrer, K., Leos-Urbel, J., Messner, E., & Riley, N. (2016.) Becoming a community school: A study of Oakland Unified School District community school implementation 2015–2016. John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities; Klevan, S., Daniel, J., Fehrer, K., & Maier, A. (2023). Creating the conditions for children to learn: Oakland’s districtwide community schools initiative. Learning Policy Institute; McBride, A. (2022, April 19). “I want students to have more than I did”: A Tiger takes the reins at Fremont High. The Oaklandside; McLaughlin, M., Fehrer, K., & Leos-Urbel, J. (2020). The way we do school: The making of Oakland’s Full-Service Community School District. Harvard Education Press; Oakland Unified School District. (2011). Community schools, thriving students: A five-year strategic plan. The prior fall, Oakland Unified announced that it would become a full-service community schools district—meaning that each school would work as a web of partnerships among staff, families, and the community to meet students’ needs.

Soon, the school hired alumna and teacher Nidya Baez as its first community school manager, and she helped open both an on-site health clinic and an integrated student supports hub designed to “identify, diagnose, and provide appropriate services to students who are not successfully engaging in school.”Fremont High School. (2012). Community schools strategic site plan: Fremont High School, school year 2012–2013. (accessed 08/11/2025). Over time, the school expanded the services and partnerships present on campus. It now works with eight different community organizations and La Clínica de la Raza, which runs the Tiger Health Clinic. In 2022, Carmen Jimenez, Fremont alumna, took over as community school manager when Baez became principal.

College and Career Readiness Supported by Voters. In 2014, Oakland voters overwhelmingly passed a parcel tax—Measure N—to fund college-preparatory and career-focused courses along with opportunities for internships and work-based learning. There were career-themed small learning communities before Measure N, but this was the first attempt to go “wall to wall” with industry-themed Linked Learning pathways. The measure also used the language of supplementing—not supplanting—funds to ensure that the money would be used as intended. The same year, California codified a new form of structured dual enrollment that allowed districts to partner with local community colleges and offer credit-bearing college courses to students in high school.Brumer, D. (2025, April 16). More high schoolers are taking college classes—but no surprise which students benefit most. CalMatters; Career Ladders Project. (2025). Equitable dual enrollment policy to practice guide. Chancellor’s Office, California Community College. In Oakland, this included sharing data between the district and the local community college and committing to providing students with the supports that would help them to be successful.

To oversee the implementation of Measure N funding at each school site, the school board established an independent College and Career Readiness Commission, composed of a broad array of community members who had ownership over the process. At the end of the school year, each high school presents its Education Improvement Plan to the commission. David Kakishiba, former Oakland Unified School Board President and current College and Career Readiness Commission member, explained that these presentations help facilitate reflection on the “incentives, language, and support structures that enable school leadership teams to … own it for themselves.” In 2022, voters reauthorized Measure N—then Measure H—for an additional 14 years.

Authentic Assessment as a North Star for Learning. In April 2025, Fremont’s presentation to the College and Career Readiness Commission highlighted students’ graduate capstone presentations, the culmination of a pathway- and community-themed yearlong research project, as an example of how Fremont is serving its students and preparing them to graduate long before senior year starts.Maier, A., Adams, J., Burns, D., Kaul, M., Saunders, M., & Thompson, C. (2020). Using performance assessments to support student learning: How district initiatives can make a difference [Brief]. Learning Policy Institute. For example, a 10th-grader in the Architecture Pathway designed their dream house as part of an interdisciplinary project between their career and technical education, geometry, and chemistry classes to learn drafting and design skills. Then, in the senior graduate capstone, the student would put what they learned in 10th grade to use, building a local structure, like a bench or a swing, while also researching and writing about the history of its location.

For Fremont students, integrated community school resources, Linked Learning pathways, and dual enrollment courses provide access to relevant, authentic, and career-connected learning supported by the resources they need. Principal Baez explained:

[A] community school is a school owned by the community; we are serving the community. … It’s not just academics; it means getting [students] jobs, job training; it means building experiences where students really feel connected to other students and staff.Community Concern Films. (2025). Rooted in Oakland.

In 2022, Fremont received an implementation grant through the California Community Schools Partnership Program to bolster its community schools approach, and in 2024, Fremont’s Architecture Pathway and Media Pathway received implementation grants through the Golden State Pathways Program to strengthen their Linked Learning programming.California Department of Education. (2025). Funding results: Golden State Pathways Program planning and implementation grant; California State Board of Education. (2025). SBE agenda for May 2022: California Community Schools Partnership Program: Approval of cohort 1 planning and implementation grantees, and Lead Technical Assistance Center contract awardee. The school also recently received a Distinguished California Partnership Academy honor for its Media Academy.

Linked Learning With Dual Enrollment and Work-Based Learning

Linked Learning combines college-preparatory coursework with an industry theme to provide students with access to both college and career opportunities after high school. Using these programs and work-based learning, including internships and apprenticeships, students can connect the learning happening in the classroom with relevant postsecondary work opportunities and get hands-on experiences with career skills.

Many Linked Learning pathways include dual enrollment classes, which provide college instruction and access to college credits right in the high school classroom. Oakland Unified has 45 Linked Learning pathways and 118 dual enrollment courses available to its students, largely supported through Measure N funding. To meet the requirements set forth in the Golden State Pathways Program, Oakland Unified and Fremont will need to use their implementation funding to expand the number of dual enrollment credits available to students.

Linked Learning pathways have three levels of certification anchored in high-quality standards to ensure quality and encourage continuous improvement: candidate, silver, and gold. Pathway administrators and school staff work with Linked Learning coaches to improve their programming and decide when they would like to apply for the next level of certification. Pathway administrators and staff work with their Linked Learning coaches and use a set of evidence-based standards to evaluate their progress before submitting their artifacts and, if going for a gold certification, hosting a site visit for evaluators.

Some pathways function as small schools in themselves, while larger comprehensive high schools typically have several Linked Learning pathways functioning as small learning communities, especially in Oakland, where they have committed to a “wall-to-wall” approach. One evaluation found that students in certified Linked Learning pathways were more likely to graduate, were less likely to drop out, and, on average, earned more credits than their peers in traditional high school programs.

Source: Linked Learning Alliance.

Designing for Relationship-Centered Schooling

One of the keys to Fremont’s success has been staff and leaders’ investment in relationships, whether that be through partnering authentically with families, its longstanding restorative justice initiative, smaller learning communities targeted to support vulnerable students like its 9th-graders and newcomers, or social and emotional learning practices. Some of these features, like authentic partnerships, emerged through the community schools approach: Collaborative leadership with shared power and voice is a key community schools practice. Others reflect one of the priorities of the original redesign: positive developmental relationships between students and their peers and between students and staff.

Authentic Family Partnership to Foster Ownership. The redesign process itself helped foster collaborative leadership. Trust between staff and families took time to rebuild and required consistent communication. The community selected two coprincipals to lead the new school. The coprincipals conducted listening tours with families and community organizers to understand families’ concerns, goals, and dreams for their students—and the reimagined high school. They spoke English and Spanish at meetings to connect with those who attended and to broaden participation. Community organizers and parent leaders both participated in and facilitated these conversations.

The community-engaged principal selection process also set a precedent for collaborative leadership. To this day, Fremont hires new staff and administrators by committee, which includes students on the hiring panel. Students are not passive; they ask tough questions, provide opinions, and push back on applicants whom they deem a bad fit. Assistant Principal Derek Boyd shared about his experience:

I interviewed with about 15–20 people, it felt like. I took that as this community, this school community, [and] all its stakeholders really care about who is leading the school, and it’s not going to be a top-down decision.Community Concern Films. (2025). Rooted in Oakland.

Boyd’s reflection is spot-on. This process is in place because families, students, and the broader community hold power on campus, and they care deeply about who is joining their community.

Restorative Practices That Build Community. Fremont has finally established a consistently positive school culture, though it did not happen overnight. Research demonstrates the pivotal role of relational trust in developing young people’s brains and the role of relationships in catalyzing meaningful change in schools. Taking part in a whole-school restorative justice approach can increase student achievement and reduce suspension rates and disparities. Smaller learning communities that divide students into cohorts and develop community can support positive developmental relationships with students and staff. A school that combines these approaches can create strong, trusting relationships that support a safe and welcoming school climate in which students can learn from their mistakes and triumphs.

At Fremont, these relationships have been instrumental in shaping how students see the role of school. Victor, a former Fremont student, observed:

School is the prime time in life to make as many mistakes as you possibly can so that you can learn from them and not repeat those same mistakes again in adult life, where they could have more drastic consequences.

Another student, Evette, added, “School is where you can be anyone without anybody judging you. A school is a place where people want to see the real you.” Three years ago, The New York Times featured Victor’s and Evette’s perspectives in a photojournalism project developed by students at Fremont about their lives. Most sophomores in the country do not see school as a place to actively make mistakes or walk around without judgment. And yet, this is how students experience school at Fremont.

The school also cultivates relationships through restorative justice. Rather than a boxed curriculum or a book upon a shelf, restorative justice is a way of looking at the world through the lens of root cause, harm, and repair. During regular advisory periods, students and staff use circles to proactively build bridges across differences and find shared experiences. During circles, one person responds to a prompt or provides a check-in while the others practice active listening until the speaker is finished. Students also repair and address conflict when it arises, or they do more sustained work to restore relationships or at least move toward a functional place if deeper harm occurs.

Small Learning Communities So That Students Are Known. Smaller learning communities also help establish trusting relationships. Freshmen are automatically put into the 9th-grade house for their first year of high school, before they select their Linked Learning pathway, and newcomer students also have their own Newcomer Education Support and Transition (NEST) pathway. While 9th-grade students are new to the school, newcomer students have recently arrived in the United States, so many things (e.g., language, culture) are new, and no two newcomer students are the same. In both spaces, students who might otherwise feel lost on a large campus have regular touchpoints with peers and staff dedicated to helping them build key skills. Staff get close with their students, learning their needs, passions, goals, and identities, which helps to ensure that no one falls through the cracks.

Advisory classes, which function as family groups that meet with a teacher regularly, are a key venue for building the trusting relationships that undergird restorative practices and the social-emotional skills that cement those relationships. All students in Oakland Unified, including those at Fremont, receive instruction in social and emotional learning. The district’s graduate profile emphasizes the following as important to develop learners who are ready to be civically engaged citizens: self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision-making, relationship skills, and social awareness. These competencies are infused throughout the teaching and learning process at Fremont, and students use advisory time to work on these skills.

These efforts combined have created a campus on which students know one another and are known by staff. In the 2023–24 California Healthy Kids Survey, 90% of Fremont student respondents reported that they felt there was a teacher or adult on campus who cared about them. Staff and families have felt a shift as well. Rather than immediately talking about gun violence, student fights, and basic safety when Fremont is mentioned, the conversation focuses on students’ nationally recognized media projects or the deep relationships with families and community-based organizations. Sometimes, it’s just about the long waiting list of families who want to send their children to the school.

The Road Ahead

Since it first began redesigning its school in 2015, Fremont has made strides. Students have access to Linked Learning pathways, dual enrollment courses, and performance assessments that allow them to choose their own adventure upon graduation, whether that is college or a career. Robust two-way partnerships and an effective community school coordinator provide necessary resources, engage families as partners in school leadership, and identify key funding streams to support the work and help students arrive ready for the classroom. Relationships provide a foundation for community-connected learning experiences at Fremont. Restorative justice, smaller learning communities, and social and emotional learning skills help bridge differences and create positive relationships that students need to thrive.

For the state, building more schools like Fremont is a priority. The governor’s 2025 Career Master Plan looks to integrate initiatives across the education, labor, and higher education sectors so that students’ learning experiences in secondary school feel more connected to their lives after high school. California’s $10 million state budget investment in a pilot program to support high school redesign will create additional opportunities for school communities to rethink how their schools are organized—like Fremont did—and redesign learning to better meet the needs of students, families, and the broader community.

Community-Connected Redesign at Fremont High School (brief) by Charlie Thompson is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This brief was supported by the Stuart Foundation and the Youth Thriving Through Learning Fund. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the author and not those of our funders.

Cover photo courtesy of Fremont High School Media Academy.