Striving for Relationship-Centered Schools: Insights From a Community-Based Transformation Campaign

Summary

While research indicates that relationship-centered environments support student learning and success, it has been difficult to redesign secondary schools based on the factory model in ways that center relationships, particularly at the secondary level. This brief focuses on efforts to advance relationship- centering schooling in high schools. It examines the Relationship Centered Schools (RCS) campaign, a youth-led effort supported by Californians for Justice (CFJ) and conducted in collaboration with educators and district leaders. The study focuses on two settings—the Long Beach Unified School District and Fresno’s McLane High School—and the efforts of local actors to center relationship-building as a catalyst for change.

The study highlights the emerging impacts of RCS efforts and the approaches that can advance relationship-centered change in schools and districts. These approaches included structures for relationship-building and professional development, which built shared knowledge and trusting relationships among those driving change, as well as practices that foster empathy-building, deep listening, and student voice. Additional enabling factors that advanced RCS work included stable support from administrator and educator champions, financial resources, and coherence between relationship-centered schools and preexisting local priorities.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

Introduction

If our young people experience all this violence outside of school and then adults are reaffirming it in the system, they’re going to go through life believing that they’re not meant to go to college or to be who they want to be or to fulfill their potential. I think that’s why relationship-centered schools are so critical. They can interrupt that internalization and help with the healing that’s necessary for a lot of young people of color.Geordee Mae Corpuz, Californians for Justice

In recent years, there has been a growing understanding that positive relationships support student learning and well-being.Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2019). Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context. Applied Developmental Science, 23(4), 307–337; Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140; Osher, D., Cantor, P., Berg, J., Steyer, L., & Rose, T. (2020). Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(1), 6–36. Research shows that youth who have positive connections with adults at their schools demonstrate higher levels of motivation, self-esteem, and prosocial behavior than their peers in less relationship-centered contexts. Relationship-centered schools also enable positive student academic outcomes, including increased attendance, graduation rates, achievement on English language arts and math assessments, and college-going rates.

While research indicates that relationship-centered environments positively support student success, it has been difficult to design schools with relationships at their foundation, particularly at the secondary level. Relationship-centered schools challenge ingrained structures that tend to foster depersonalization in secondary settings. These structures include the common practice of having students attend seven or eight classes daily for short periods, which can make it difficult for youth to be well-known by and connected to a caring adult. In turn, many secondary students attend schools that provide few opportunities to develop positive connections, and the entrenched structures can be at odds with the developmental needs of adolescents, particularly among youth experiencing the effects of poverty, trauma, racism, and other forms of discrimination.

Why Relationships Matter for Learning and Well-Being

The science of learning and development (SoLD) is a growing body of interdisciplinary research that demonstrates how positive bonds and connections catalyze learning and growth. Evidence from this body of research indicates that positive relationships:

- enhance students’ motivation, sense of self-efficacy, and higher-order thinking;

- allow adults to more accurately perceive and respond to a young person’s needs; and

- mitigate the harmful effects stemming from excessive stress and adversity that students may experience, which can improve students’ readiness to learn.

SoLD research also identifies qualities that make relationships impactful in young people’s lives. It demonstrates that positive relationships are developmental, whereby they help students develop a positive self-concept and foster the capacity for self-direction. Relationships that are trustful, caring, and culturally responsive also optimize student learning, well-being, and agency.

This brief focuses on one relationship-centered high school transformation effort—the Relationship Centered Schools (RCS) campaign, a youth-led effort supported by the community-based organization Californians for Justice (CFJ) and conducted in collaboration with practitioners and district leaders. Based on interviews with CFJ organizers, district and school leaders, educators, and former youth organizers, this brief highlights RCS work in two settings—the Long Beach Unified School District and Fresno’s McLane High School. The cases demonstrate how local schools and districts have furthered relationship-centered schooling, the conditions and factors that have influenced RCS work, and the emerging impacts of RCS efforts.

The Relationship Centered Schools Campaign

CFJ is a statewide organization with a mission to unlock the power of student voice and agency. It aims to give young people the skills to become community leaders who organize their peers to take action while deepening their understanding on issues of systemic racism, education inequity, and other forms of discrimination.

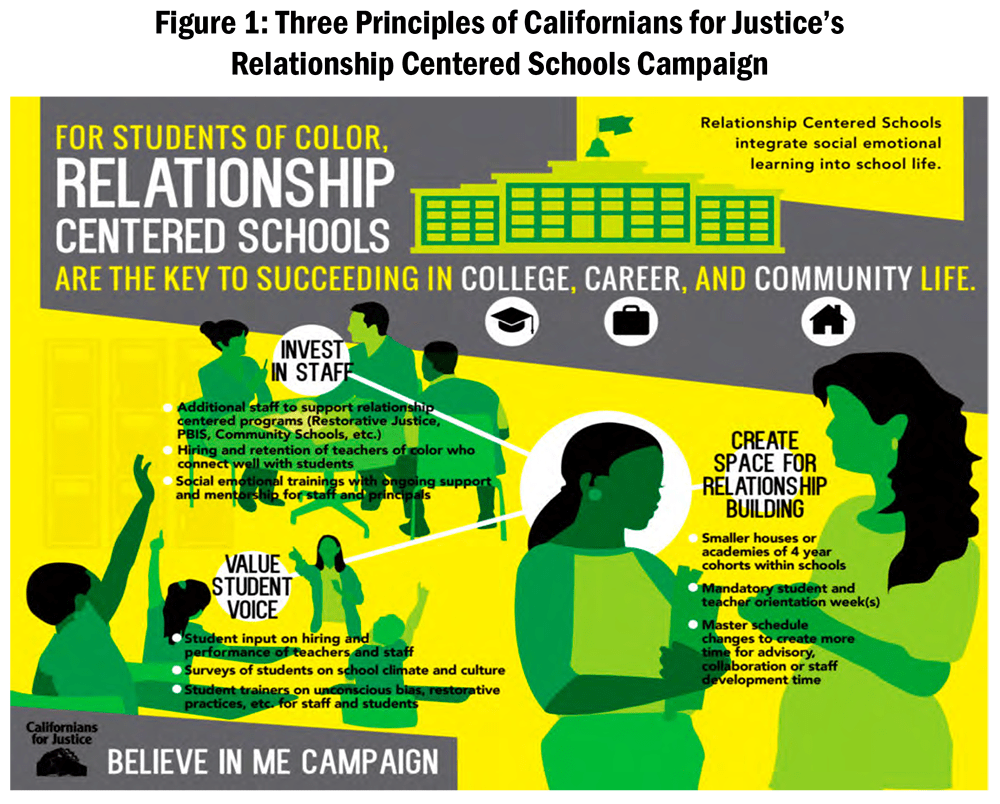

The RCS campaign, launched in 2015, is one of CFJ’s initiatives. The campaign began on the heels of youth-led action research that investigated a pattern that had surfaced in a statewide student survey—that more than 40% of surveyed 9th-graders and 11th-graders indicated that it was “not at all true” or was “a little true” that there was a teacher or other adult who really cared about them. In turn, CFJ and youth leaders initiated the RCS campaign, centering three principles to guide action and school improvement: (1) create space for relationship building, (2) value student voice, and (3) invest in staff. (See Figure 1.)

In its approach to change, the RCS campaign embodies the dimensions of the community organizing cycle, which seeks to build collaborative power in relationship-centered and incremental ways and to elevate the voices of often marginalized groups in change efforts. To do this, CFJ organizers and youth build relationships with school administrators, educators, and district officials and engage in ongoing conversations with them to increase their knowledge of and investment in relationship-centered and antiracist approaches. Through these discussions, students and CFJ organizers seek to build connections and allyship with educators and leaders, surface common concerns that can ground their collective vision for change, and ultimately inform codetermined action steps to improve the quality and tenor of school relationships.

RCS in Action: The Long Beach Unified School District

The Long Beach Unified School District (Long Beach Unified) serves more than 67,500 students across its 85 schools, a greater proportion of whom are students of color and students from low-income backgrounds compared with the California state average. For more than 2 decades, the district has been recognized for achievement among its diverse student population,Burns, D., Darling-Hammond, L., & Scott, C. (with Allbright, T., Carver-Thomas, D., Daramola, E. J., David, J. L., Hernández, L. E., ... Talbert, J. E.). (2019). Closing the opportunity gap: How positive outlier districts in California are pursuing equitable access to deeper learning. Learning Policy Institute; Park, V. (2019, October). Bridging the knowing–doing gap for continuous improvement: The case of Long Beach Unified School District. Policy Analysis for California Education. yet local leaders saw opportunities for continuous improvement in light of some troubling outcomes.

For instance, in 2018–19—as RCS work in the district was underway—chronic absenteeism among Long Beach Unified high schoolers was higher than the state average. In addition, results from a statewide survey indicated that almost one third of the district’s high school students did not agree or strongly agree that their school maintained a climate that supported their learning, their sense of safety and belonging, and/or clear and fair rules and disciplinary processes. These outcomes suggested that Long Beach Unified high schools maintained room for growth in cultivating healthy school-based attachments and implementing social and emotional supports.

Collaborating to Improve Youth–Practitioner Relationships

Long Beach Unified has historically incorporated some structures in its high schools that can enable trusting and consistent relationships between adults and students, which in turn support student learning. For instance, the district has instituted linked learning pathways—smaller learning communities in which student cohorts take classes with a common set of teachers for much or all of their coursework—as well as block scheduling, both of which can create opportunities for students to be better known and supported by staff.

At the same time, several interviewees noted that these relationship-centered structures alone were insufficient for helping students feel known and included in schools. As Deputy Superintendent Tiffany Brown put it, “I don’t think the structure of the schedule or [other structures] prompt relationship-building, but teachers who form relationships well with students really capitalize on having more time. ... Collaboration looks as collaborative as the person will allow it to be.” With this assessment, leaders and practitioners in Long Beach Unified acknowledged that more work needed to be done, and a collaboration between the district and CFJ to improve the relationship-centered and equitable character of its schools ensued.

Regular communication and engagement among district and school leaders, CFJ organizers, and youth leaders characterized early RCS efforts in Long Beach Unified. These conversations helped build relationships and served as opportunities to introduce leaders to the RCS campaign. They also enabled leaders, youth, and CFJ organizers to find common ground and purpose. As the partnership among leaders, youth, and CFJ organizers solidified, particular RCS structures and practices—aligned with CFJ’s three RCS principles—began to emerge.

Emerging Relationship-Centered Approaches in Long Beach Unified

Each Long Beach Unified educator and leader described increasing attention to empathy-building across the district as a result of RCS efforts. A frequently mentioned approach was the use of empathy interviews, a deep listening practice that seeks to cultivate care, interest, and a sense of shared humanity among those engaged in the conversation. (See “What Are Empathy Interviews?”)

Interviewees noted that empathy interviews were a central practice in newly instituted Learning Days, which provide opportunities for educators, leaders, and high school students to learn alongside one another and discuss equity-focused topics. In this forum, attendees are introduced to empathy interviews and subsequently provided an opportunity to observe them in action and reflect on the process and its impact. One former high school principal who participated in empathy interviews during a Learning Day and later engaged her staff in this activity noted the power of the interviews in changing perspectives:

There was a level of respect that [students and teachers] had for one another when they got in the room and started grappling with what would work and what wouldn’t work at our school. Everybody came away and said, “I have a different respect for our students’ perspective” or “I have a different respect for teachers.”

Long Beach Unified educators and administrators also expressed that participation in empathy interviews spurred a growing appetite to create more opportunities for building relationships and deepened their understanding of the issues that students faced.

What Are Empathy Interviews?

Empathy interviews are “one-on-one conversations that use open-ended questions to elicit stories about specific experiences that help uncover unacknowledged need.” The interviews are guided by open-ended questions that are tailored to the purpose of the interaction and can range from surfacing challenges in schools to surfacing change ideas. These questions are accompanied by probes like “Tell me more” or “Why?” to ensure that the points of view are well-articulated. Each person engaged in the empathy interview is both an interviewee and an interviewer, allowing for each individual to share their perspective and to understand the point of view of the other.

Empathy interviews require norms, skills, and mindsets. These include allotting ample time for each person to share their thoughts without interruption, actively listening, and remaining aware of one’s biases, including those related to power dynamics among school actors.

Although it was less frequently cited, the growing practice of shadowing students was described by interviewees as an empathy-building exercise. Specifically, administrators shadowed a select number of students throughout the school day to garner a better sense of their experiences, taking time to reflect on their observations and the challenges and opportunities students faced. District leaders noted that because of the insights gained from engaging in these empathy-building activities, school administrators were increasingly considering how they could center the student perspective to support instruction and a positive climate at their schools.

In addition to empathy-building, RCS efforts in Long Beach Unified spurred the creation of shared learning opportunities, where youth, school and district leaders, and educators convened to build relationships and collaboratively learn about equity-oriented topics. Implicit bias trainings and the district’s Learning Days were cited as prominent examples of shared learning opportunities. These learning opportunities, which occur outside of school hours and are attended on a volunteer basis, are student-led and include direct learning on a focal topic as well as community-building activities.

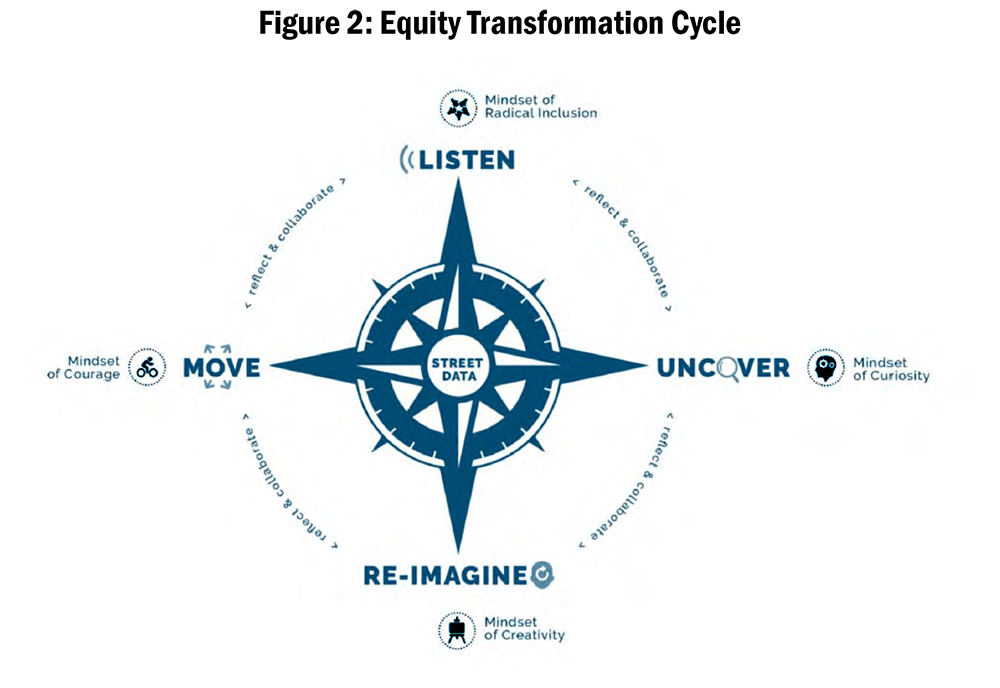

Long Beach Unified also established an Equity and Inclusion Relationship Centered Schools Professional Learning Network (PLN), which engages participating adults and students in the equity transformation cycle to inform data-driven improvement. (See Figure 2.) PLN members collect and analyze data that draw on the knowledge and experiences of students and families; with this knowledge, PLN members then design and/or suggest improvements to school practices and policies. Moreover, they engage in collective learning in ways that center student voice and racial equity in content, focus, and processes. PLN participants noted that this learning opportunity helps school actors address equity concerns in ways that challenge hierarchies of authority and expertise in schools while building relationships. In addition, they described how engaging in the equity transformation cycle sparked changes in school policy and practice. For instance, in identifying equity challenges, PLN participants described proposed changes to uniform policies to make them less discriminatory, as well as enhancements to schools’ physical environments to reflect the fuller cultural spectrum represented in the local community.

As forums for relationship-building and shared learning emerged, leaders have sought systematic ways to elevate student voice in decision-making and strategic planning as part of their RCS efforts. Instituting school- and district-level design teams was one way this took form. Equity design teams gathered select administrators, parents, educators, and students to identify equity challenges, collect data to diagnose the problems, and ultimately propose changes. In addition to acknowledging the design teams, interviewees mentioned the growth of student advisory committees across the district. Every Long Beach Unified principal established these committees—with representatives from various linked learning pathways—to support principals in thinking about school climate and community-building. Long Beach Unified’s Superintendent, Jill Baker, similarly created a Student Advisory Committee to advise on key issues that affected student experiences.

According to Long Beach Unified officials, student participation in these forums has influenced how administrators approach their work. Superintendent Baker articulated the impact that this relationship- and student-centered approach had across the district:

We’ve seen much more attention to having students at the table and incorporating student voice. ... It’s an outgrowth of the philosophy of RCS but also really operationalizing some of the strategies and some of the moves that we think are important to making our schools more equitable learning environments and better places for all students.

RCS in Action: Fresno’s McLane High School

McLane High School (McLane), which serves more than 2,000 students, is one of Fresno Unified School District’s 106 schools. Almost 74% of McLane’s students are Latinx, just under 25% are English learners, and about 96% are categorized as socioeconomically disadvantaged—statistics that reflect a higher proportion of these demographic subgroups when compared to the district and California averages.

McLane has supported its diverse students in graduating and in completing California’s college preparatory course series (i.e., A–G course requirements) at greater rates than the district average. However, other outcomes have suggested areas for improvement. For instance, in 2018–19, as the RCS campaign was taking root, McLane had slightly higher rates of chronic absenteeism when compared to the district average. In addition, only 63% of McLane students agreed or strongly agreed that their school cultivated a culture and climate that supported their learning and a sense of safety and inclusion, which was slightly lower than the district average. These metrics signaled that efforts to improve the quality of relationships and other systems of support were likely needed to grow students’ sense of belonging and connectedness to the school environment.

Restorative Practices as a Foundation for RCS Efforts

The seeds for McLane’s commitment to relationship-centered schooling were sown with its schoolwide engagement with restorative practices—approaches that build relationships among practitioners and students while supporting reflection, communication, and problem-solving in the face of emerging issues.Klevan, S. (2021). Building a positive school climate through restorative practices [Brief]. Learning Policy Institute. In 2013–14, McLane was selected as one of six pilot sites in the Fresno Unified School District to adopt restorative practices as a strategy for improving school climate. As a pilot site, the school was allocated key resources to support implementation of the practices.

Among these resources were restorative practice school counselors who were embedded in pilot sites for multiple years to build practitioner capacity and the schools’ restorative approaches. Rebecca Alemán has served as McLane’s Restorative Practice School Counselor since 2014 and has facilitated ongoing professional development to build the skills, mindsets, and school culture that support care-driven implementation of restorative practices. This included attention to the role of relationships in supporting youth learning, development, and engagement.

When the school was identified as a site for Fresno Unified’s Student Voice/Relationship Centered Schools campaign in 2017–18, McLane built upon its foundational learning around restorative practices to increase attention to other important dimensions of relationship-centered schooling. In this work, McLane established a collaborative partnership with CFJ organizers, who increasingly engaged with school leaders, practitioners, and youth on the campus to grow relationships and knowledge of RCS and racial equity work.

Relationship-Centered Structures and Practices at McLane High School

As part of its RCS efforts, McLane sought to improve established relationship-building structures, particularly the school’s biweekly homeroom period, which formed small communities for McLane’s large student population and enabled consistent, multiyear connections. In codifying this forum as part of a redesign of the school’s master schedule, school leaders hoped homeroom periods would create consistent opportunities for relationship-building among students and teachers. However, they acknowledged that the connections made in these periods varied in quality and tenor.

To support relationship-building in homeroom, the school pursued a new solution—to empower students to lead homeroom community-building. McLane identified student facilitators and provided them with opportunities to develop their skills. Youth explicitly learned the motions of doing a community-building circle and practiced facilitating circles with the group to receive feedback and hone their abilities. They also engaged in their own social and emotional learning to build their communication skills, self- and social awareness, and relationship management. With this training, pairs of youth facilitators were dispatched to six homerooms prior to the pandemic-induced school closures in March 2020. In addition, trained youth leaders, with the support of Alemán and other staff, provided professional development that guided teachers in facilitating community-building circles. While areas for improvement around student-facilitated homeroom remained, administrators and practitioners at McLane were optimistic about the precedent it set for their school culture.

In addition to seeking improvements to the school’s homeroom structure, McLane leaders and staff sought to create new avenues for elevating student voice as part of their RCS work. This entailed bringing more diverse student representation into decision-making spaces, including the Principal’s Advisory Council. Traditionally, the council had been composed of administrators and elected department chairs who reviewed school policies, yet internal discussions among council members revealed a growing interest in expanding representation to include students who could lend important insights into pedagogical practice and school climate.

Once student representation from a broad cross-section of campus was secured, the council operated similarly to a focus group in which practitioners listened to students about what was happening in classrooms and the broader school environment, according to McLane Principal Brian Wulf. Through their presence in and contributions to advisory council discussions, student representatives lent their insights to identify areas of strength and struggle at McLane—insights that led to some policy and practice changes, according to school leaders.

With the insights garnered from students in decision-making spaces, practitioners and leaders at McLane also noted that student voice was a growing feature of the school’s professional development opportunities. For example, students were invited to attend select full-staff meetings or convenings of McLane’s Culture and Climate team to inform and support staff reflection and improvement processes.

The Relationship Centered Schools Campaign and Its Influence in Fresno Unified School District

Youth leaders and Californians for Justice (CFJ) organizers also worked within Fresno Unified School District to support relationship-centered practices across the district. Much of this work has sought to support and inform the development of the district’s Local Control and Accountability Plan (LCAP). In practice, this has meant creating opportunities for meaningful engagement for youth and communities in the district’s LCAP process, which ultimately informed the district’s decision to allocate resources to restorative justice and the Relationship Centered Schools (RCS) campaign.

In addition to LCAP-related efforts, those engaged in the RCS campaign have supported districtwide professional development. Specifically, youth leaders, in partnership with CFJ, held learning sessions on topics such as implicit bias that were open to practitioners across the district and attended on a volunteer basis. Furthermore, RCS efforts have spurred the district to consider modifications to its school climate survey so that it includes more substantive attention to relationships and student voice.

While RCS efforts remain ongoing at McLane, interviewees noted that engaging in this work has begun to spur change. According to administrators and teachers, McLane educators had become more inclined toward and well-versed in relying on relationships as initial and primary ways to identify and address emerging challenges. Moreover, some interviewees expressed that the emphasis on relationships at McLane had also resulted in changes in school culture. Alemán’s reflection on her tenure at McLane provides insights into these shifts:

To think about that first mindset stepping onto this campus and hearing, “If we listen to kids, they’re going to run the show. There’s going to be chaos.” ... To now, with the pendulum swinging and to come far enough to where that’s not the first thought. … This is a culture where we listen to students first—where we get to know them. To be able to witness that transformation is incredible to me.

Factors Enabling Relationship-Centered Change

While the campaign is ongoing and bounded in scope, evidence from the campaign provides insights into the structures and processes that can increase opportunities for positive teacher–student relationships to develop. These approaches, which can inform others seeking to advance relationship-centered change in their schools and districts, include:

- Establishing structures for relationship-building. Structures for relationship-building among youth and school adults created consistent opportunities for students to be known, seen, and connected to a caring adult. In Long Beach Unified, these structures included the creation of shared learning opportunities and attention to empathy-building practices, while efforts to improve the relationship-centered character of the school’s homeroom structure and increased opportunities for student voice characterized RCS work at McLane. These incremental activities represent important steps in creating consistent opportunities to ensure all students are known, seen, and connected to a caring adult.

- Building trusting relationships among those driving change. RCS implementation was built and sustained through consistent engagement and partnership among the youth, educators, district and school leaders, and CFJ organizers who were leading RCS efforts. Interviewees described how these opportunities cultivated meaningful dialogue, shared investment, and a deeper understanding of the work.

- Creating opportunities for professional development. Shared learning experiences (e.g., Learning Days, dedicated professional learning communities, student participation in professional development sessions) allowed leaders, educators, and youth to learn with and from each other and to build common knowledge about relationship-centered change. As such, the experiences were identified as important in furthering relationship-centered schooling.

- Fostering empathy-building and deep listening practices. By developing their capacity to engage in activities that develop empathy, including empathy interviews and other opportunities that surface insights into students’ schooling experiences, youth and adults built connections that spanned age, identity, and traditional lines of authority—which served as an important foundation for the equity-oriented work of transforming schools to be relationship centered.

- Elevating and valuing youth voice. Youth shared their experiences and lent their insights and perspectives to change efforts through RCS structures and forums instituted at McLane and in Long Beach Unified, including those that enabled increased and diverse youth representation in decision-making forums and professional learning settings. Their perspectives helped to surface ongoing challenges and, at times, potential remedies that could support equitable, relationship-centered practices.

- Finding coherence between relationship-centered schooling and preexisting priorities and initiatives. When RCS work aligned with or reinforced efforts already underway, like initiatives promoting the use of restorative practices, it was more readily embraced because it was more easily understood as enhancing other initiatives. Moreover, congruence between RCS and other initiatives allowed practitioners and youth leaders to leverage emerging structures, routines, and commitments to grow RCS practice among site and district actors.

- Cultivating the support of administrator and educator champions. In its early phases, the RCS campaign often engaged a subset of educators and administrators who helped RCS gain visibility and traction. Stability among leaders and educators was reported to help deepen and sustain the work, as stability provided continuity to change efforts and helped with the onboarding of educators and administrators when there was turnover.

- Allocating fiscal resources to support relationship-centered approaches. Investments related to relationship-building structures and capacity-building (e.g., stipends for participation or leadership in professional development opportunities related to RCS) allowed youth and practitioners to collectively learn about supporting student learning and well-being, communicated the district’s commitment to the transformation effort, and acknowledged the time that practitioners and youth leaders expended in this critical work.

Striving for Relationship-Centered Schools: Insights From a Community-Based Transformation Campaign (brief) by Laura E. Hernández and Eddie Rivero is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Californians for Justice Education Fund. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.