Fostering Belonging, Transforming Schools: The Impact of Restorative Practices

Summary

Across the country, many schools have adopted restorative practices in an effort to improve school climate and student outcomes while reducing exclusionary discipline. Restorative practices are designed to proactively build community, improve relationships, and help students amend harm when conflict occurs. Using 6 years of student survey data and California administrative data, this study examines the use of restorative practices in 485 middle schools and their impact on school and student outcomes. Analyses find that exposure to restorative practices improves students’ academic achievement and reduces suspension rates and disparities. Schools that increased use of restorative practices saw a decrease in schoolwide misbehavior, substance abuse, and student mental health challenges, as well as improved school climate and student achievement. Students of all racial and ethnic backgrounds benefited from restorative practice exposure, with Black and Latino/a students benefiting the most.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

Restoration, Not Exclusion

I dropped out of school—actually, they kicked me out—because I didn’t want to give them my hat. It was real zero tolerance! I was expelled for defiance for putting a hat in my backpack instead of giving it to them. And I had had bad experiences since preschool, so it was easy for me to be like “[forget] this.”

Darius RobinsonAll student and school names have been replaced with pseudonyms to protect student privacy. was a student in the Oakland Unified School District when he had the experience described above. Before the district implemented restorative practices, Darius experienced frequent exclusions from school. His first suspension occurred in preschool, and harsh punishment followed him like a specter throughout elementary school. When he was expelled in high school for a minor act of defiance, he chose to drop out of school entirely. Darius’s experience is alarmingly common: In 2014, for example, 18% of Black boys across the nation received out-of-school suspensions, and Black students across educational contexts experience elevated exposure to exclusionary discipline.Government Accountability Office. (2018). Discipline disparities for Black students, boys, and students with disabilities.

Many schools use suspensions and expulsions with the intent of deterring student misbehavior and protecting other students from exposure to misbehavior. Although exclusionary discipline is often implemented with good intentions, research has found that it increases rather than deters misbehavior, while also increasing risks of dropout, mental health challenges, and juvenile and adult incarceration. Moreover, exclusionary discipline is applied unevenly. For example, Black students are nearly 4 times more likely than White students to receive an out-of-school suspensionGovernment Accountability Office. (2018). Discipline disparities for Black students, boys, and students with disabilities. and are subjected to harsher discipline than White students for the same behaviors.Okonofua, J., & Eberhardt, J. (2015). Two strikes: Race and the disciplining of young students. Psychological Science, 26(5), 617–624. Students with disabilities are also more likely to experience exclusionary discipline than their peers.

There is growing recognition that a positive school climate is a necessary building block to support student learning. As an alternative to exclusionary discipline, some schools have adopted restorative practices, which are designed to proactively improve relationships and to mend harm when conflict occurs—all without excluding students from school. There are two main categories of restorative practices:

- Community-building practices: Practices designed to foster an interconnected school community and healthy school climate, such as community-building circles that help students and staff deepen relationships.

- Repair practices: Practices meant to bring together all stakeholders to resolve issues and take productive steps in the future, such as conflict-responsive dialogues, mediation, and harm-repair circles.

Darius was ultimately able to experience the benefits of this approach. After he dropped out of school, he joined a gang and eventually was arrested. Darius was given two options: return to school or go to jail. He chose school. And while he had assumed he would eventually drop out again, things did not go as he expected. The new school, Alice Walker Academy, had recently adopted restorative practices, which made a world of difference to Darius. As he recalls:

[After 2 weeks of circles at Alice Walker Academy], I realized it was the first time in my life I ever wanted to be at a school! Like, “We got circle today, I gotta go!” I wanted to be in class, do projects, interact, be one of the first students called on. I felt good being up here! ... All my friends [from before I went to Alice Walker Academy] are dead or in jail. Without [restorative practices], I’d probably be dead or in jail too.

Darius’s experience is similar to those of others across the country who have experienced restorative practices in their schools. However, the effectiveness of these practices has not been well understood. Prior research has focused on the effectiveness of schools adopting restorative programs, which have not always shifted school policies and staff behavior, rather than the pervasive presence of restorative practices. This research is the first to directly examine the effects of restorative practices. Using 6 years of student survey data and California administrative data, this study examined the use of restorative practices in 485 middle schools and their impact on a range of student and school outcomes.

Measuring Restorative Practices

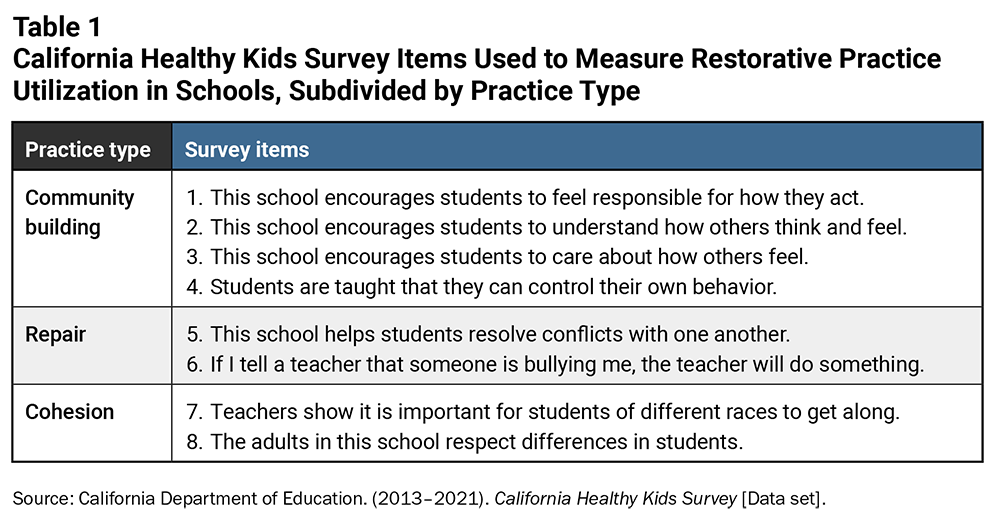

This study measured the extent to which students experience restorative practices by averaging their scores on an eight-item scale constructed from survey questions in the California Healthy Kids Survey. The items, measured on a 5-point Likert scale, cover three core areas of restorative practices (see Table 1):

- Community building: Practices designed to inculcate social and emotional skills necessary to resolve conflicts and deepen connections.

- Repair: Practices designed to facilitate students’ processes of conflict resolution.

- Cohesion: Practices designed to ensure a cohesive school community.

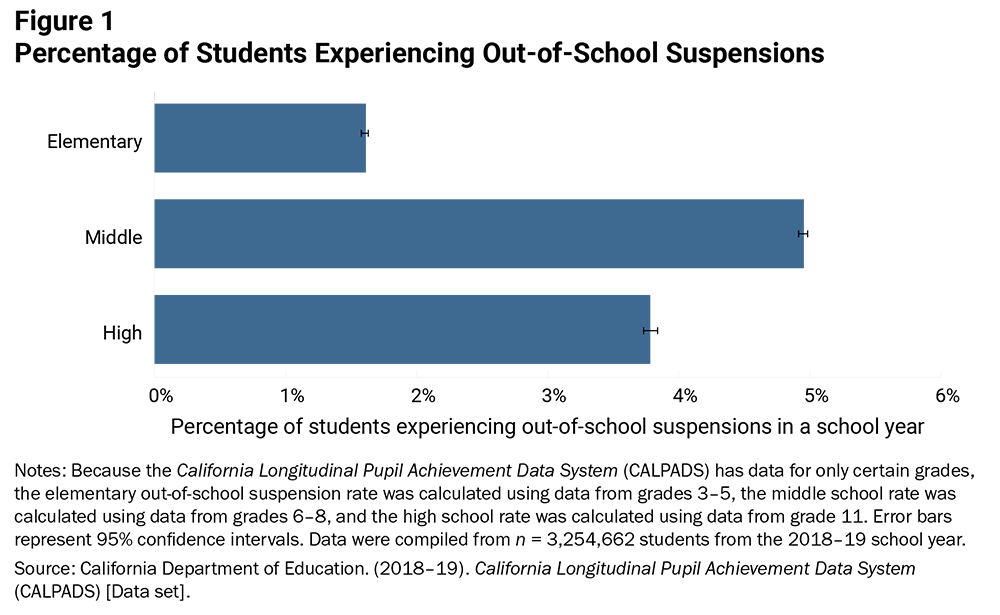

The study focused on middle school students (6th- to 8th-graders) and students who are entering middle school (i.e., transitioning from 5th to 6th grade) because middle school presents a moment of escalated risk of exposure to exclusionary discipline, and the transition from 5th to 6th grade can be a defining moment for students’ disciplinary trajectories. As Figure 1 shows, middle school students in California experienced disproportionately more out-of-school suspensions than those in either elementary or high school.

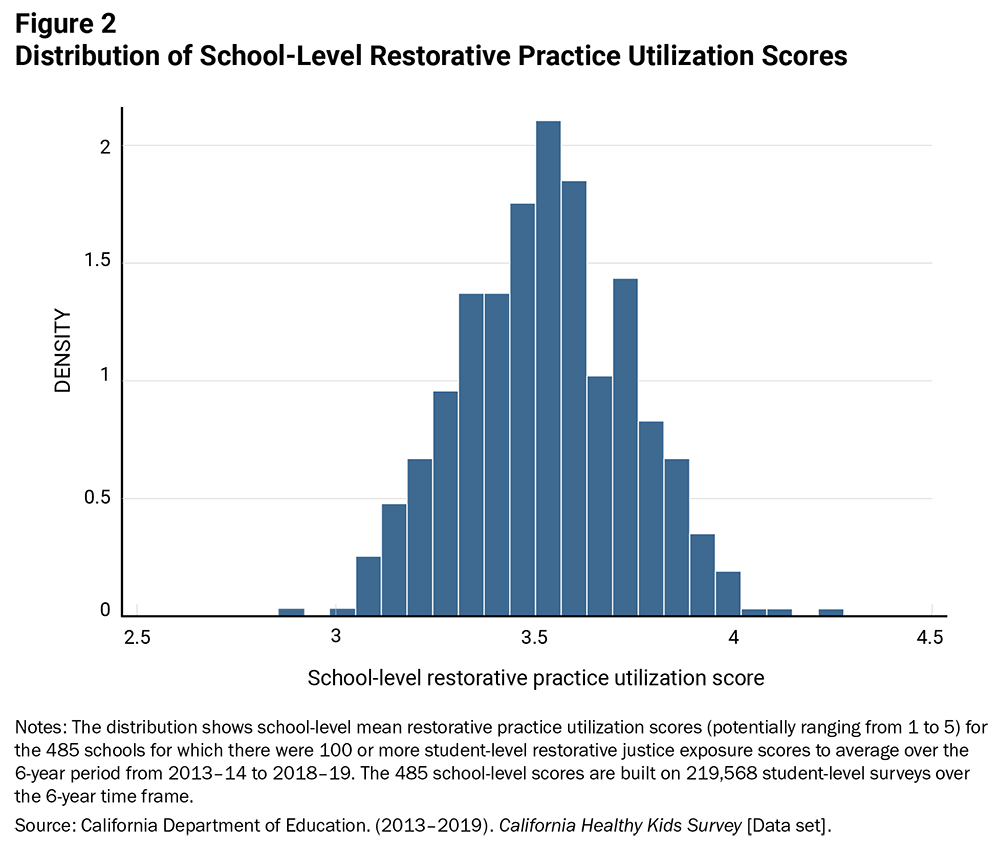

The study examined schools’ use of restorative practices by averaging students’ restorative practice scores for each school from 2013–14 through 2018–19. This analysis found wide variation in the extent to which students at different schools experienced efforts to build community, empathy, respect, and a sense of responsibility for others, as well as opportunities to learn strategies for managing emotions or resolving conflict (see Figure 2).

Students Benefit From Experiencing Restorative Practices

Looking at the experiences of students who transitioned to another school between 5th and 6th grade provides a way to see how an increase or decrease in access to conflict resolution practices affects their academic achievement and disciplinary experiences. The analyses show that, controlling for all student characteristics, increased exposure to conflict resolution practices during the transition from 5th to 6th grade significantly improved students’ standardized test performance in both English language arts and mathematics, decreased the probability of experiencing a suspension in a given school year, and decreased the number of days suspended. Effects were stronger for Black and Latino/a students than White students, suggesting that increasing exposure to these practices could help reduce stubborn gaps in academic achievement and discipline.

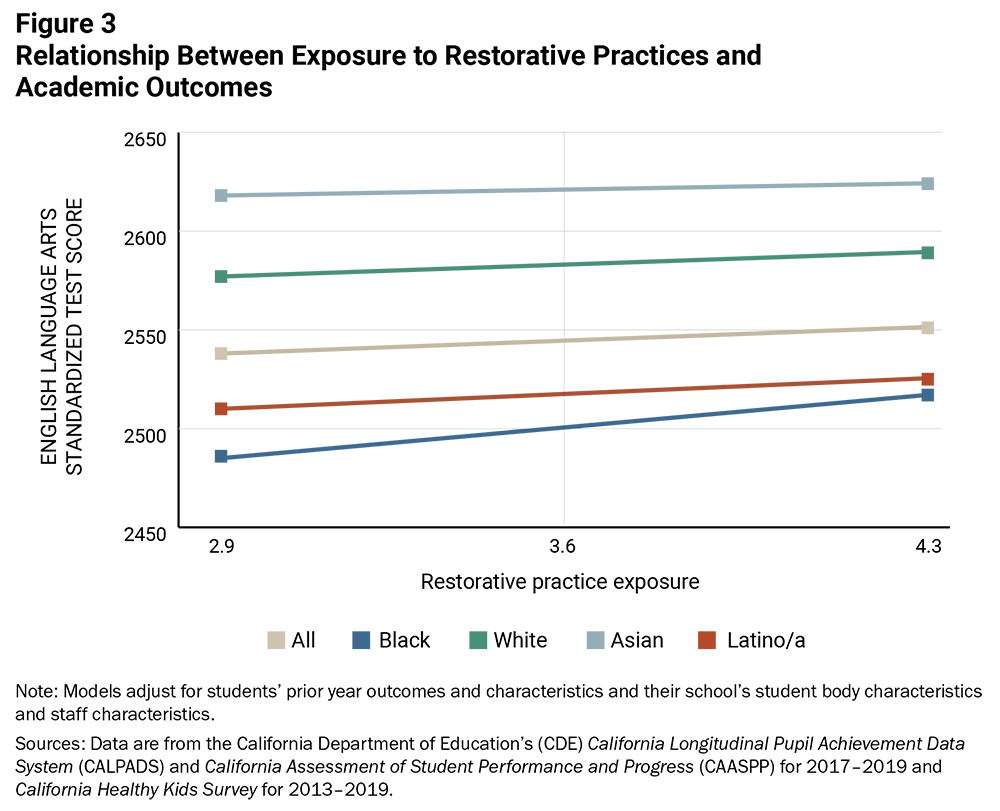

In addition to this analysis of change in conflict resolution exposure over multiple years, the study looked at how middle school students’ exposure to the full set of restorative practices in 1 school year (in 2018–19) was associated with their outcomes in that year. This analysis also indicates that exposure to restorative practices is associated with better academic achievement and smaller racial disparities in academic achievement. Figure 3 shows that greater exposure to restorative practices is associated with increased English language arts scores for all student groups, with the greatest impact for Black students. A 1-unit increase in restorative practice exposure is associated with a 7-unit increase in English language arts scores for White students and a 17-unit increase for Black students. These patterns emerge in analyses of mathematics achievement as well.

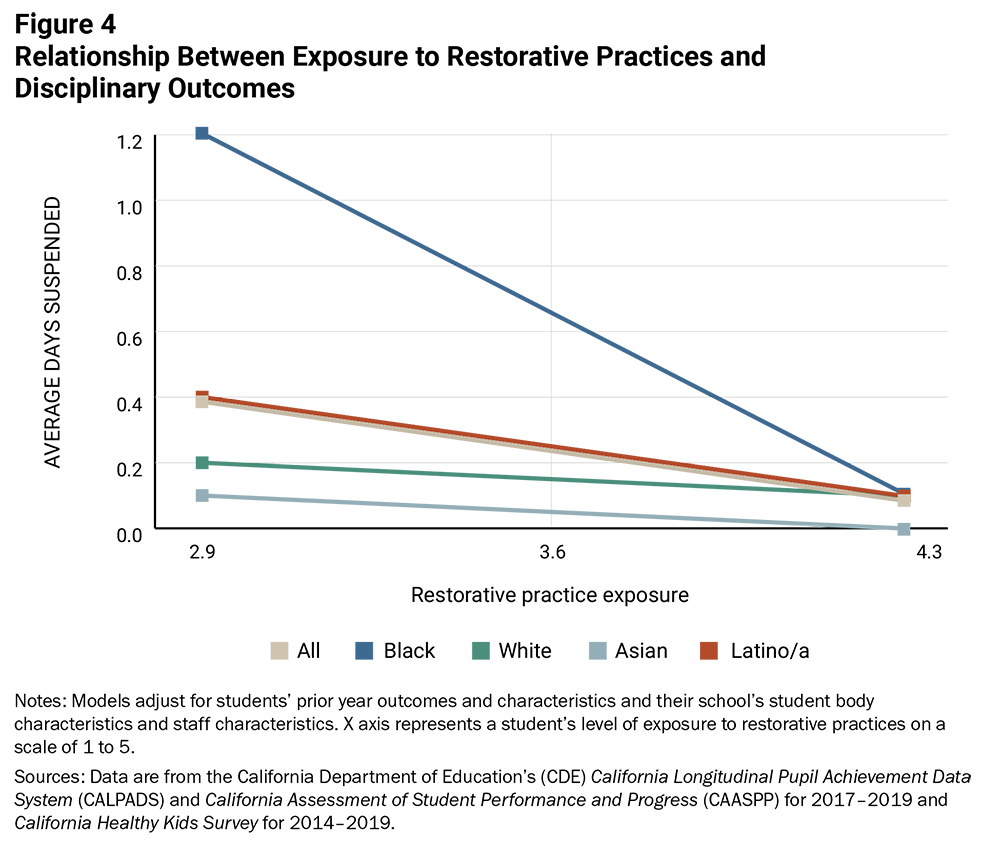

Similarly, increased exposure to restorative practices is associated with a decrease in the number and duration of suspensions for all students (see Figure 4). Again, the benefits were most pronounced for Black and Latino/a students, suggesting that expanding practices could help reduce gaps. Most notably, when Black students are exposed to restorative practices, they see a decline in days of out-of-school suspension 15 times stronger than that of White students who are exposed to these practices.

Because associations are stronger in all student-level measures for Black and Latino/a students than for White students, all else being equal, these findings indicate that racial gaps decrease with more restorative practice exposure.

Schools Benefit From Implementing Restorative Practices

The school-level effects of adopting restorative practices and implementing them well are measured by examining schools’ restorative practice scores at two separate time periods: an average score for 2013–14 through 2015–16 as compared to the same school’s average score for 2016–17 through 2018–19. Controlling for other school characteristics, including changes to the student body composition, the analyses found schools that increase use of restorative practices saw multiple schoolwide benefits.

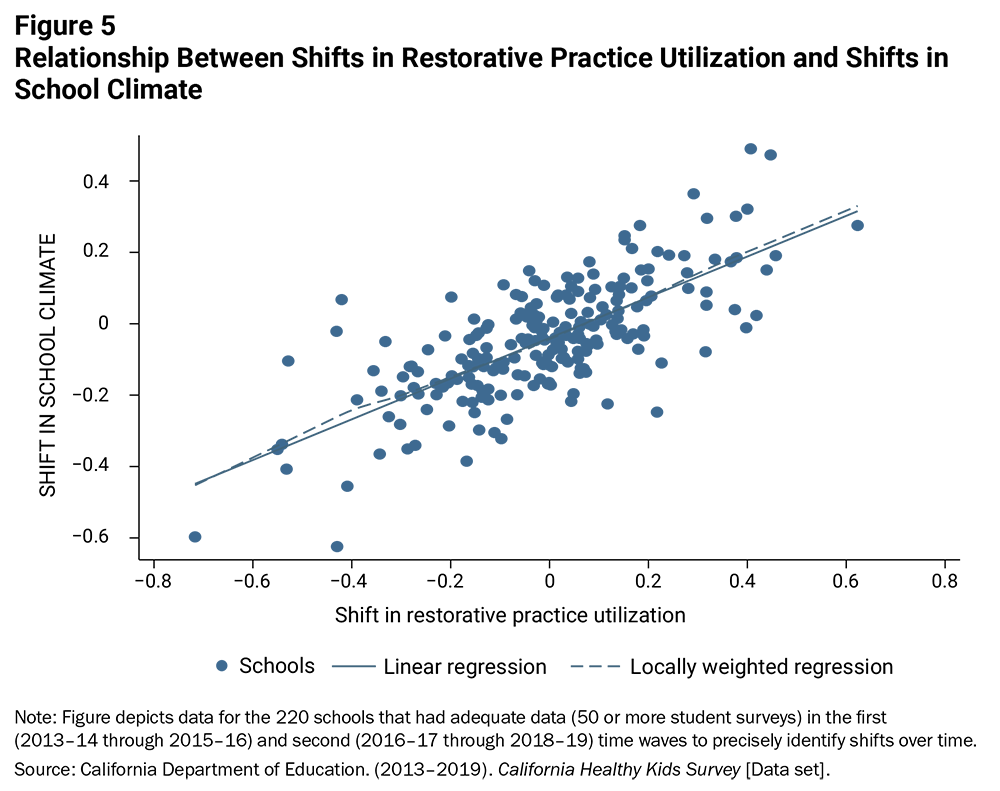

First, schools that increased their restorative practice utilization generally saw improvements in school climate. Equally important, schools that reduced their utilization of restorative practices generally saw school climate diminish (see Figure 5).

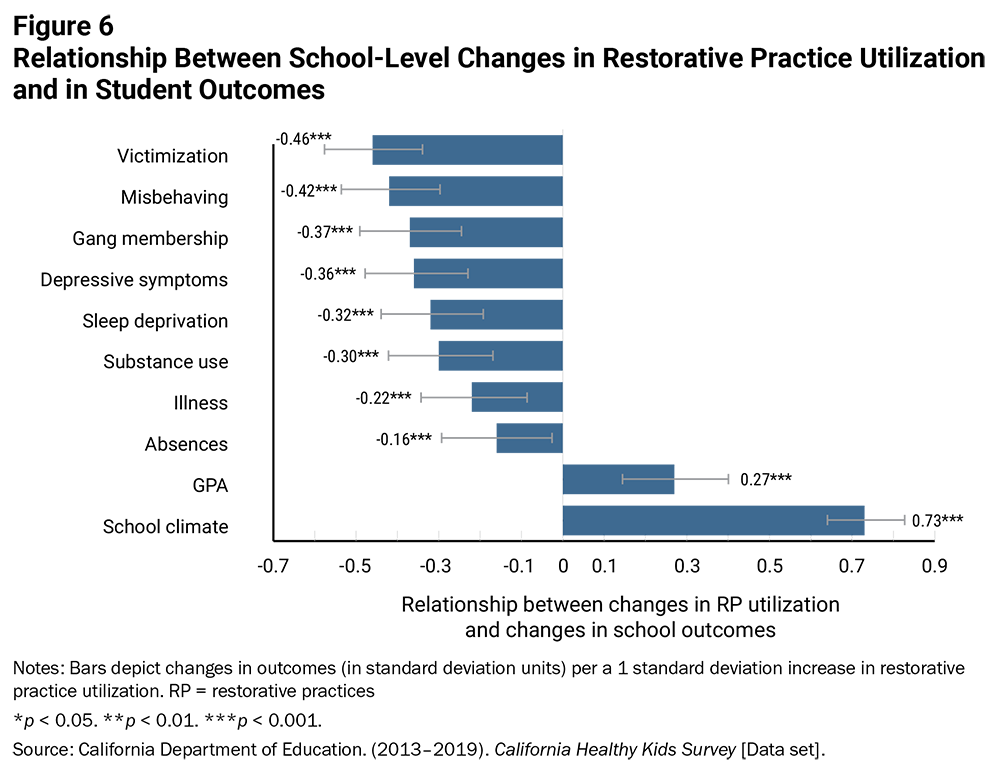

As shown in Figure 6, increased utilization of restorative practices also caused schoolwide:

- reduction in behavior and safety issues, including rates of misbehaving, gang membership, substance use, and victimization;

- improvement in student health, including lower rates of depression, sleep deprivation, and illness; and

- improvement in educational outcomes, including reduced absence rates and improved GPAs.

Access to Restorative Practices Varies

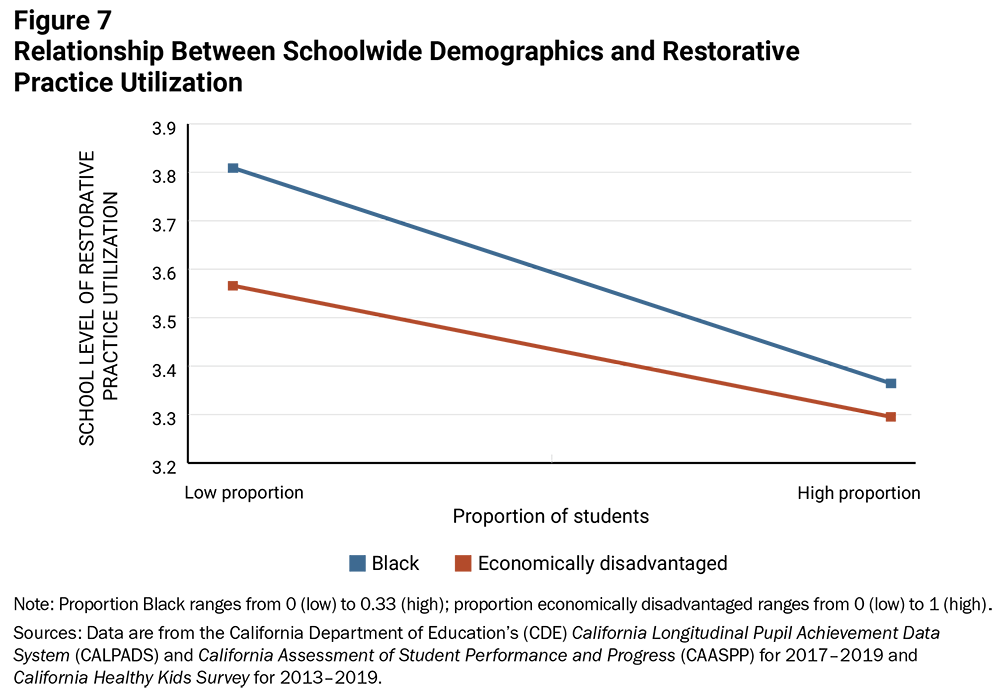

Confirming the relationships between restorative practices and positive outcomes begs the question: Who is gaining exposure to these beneficial practices? As depicted in Figure 7, even after controlling for a range of other school-level factors, schools with higher proportions of Black students or students from low-income families evidenced lower levels of restorative practice utilization. For example, students in schools in which 0% of students are economically disadvantaged have restorative practice exposure scores of 3.8 (out of 5), but students in schools in which 100% of students are economically disadvantaged have exposure scores of 3.4.

Implications

Any school or district adopting restorative practices will have its own unique journey. However, prior research and implementation guides point to approaches that may help schools and districts to overcome typical implementation challenges and to accelerate the impact of restorative practices.

Shifting from a culture of exclusion to a relational culture. To ensure restorative practices realize their intended impacts, schools can commit to a cultural transformation. This requires ensuring community members understand that punishment can be harmful and may cause misbehavior; helping staff recognize that relational approaches can improve behavior; and abandoning practices that are incompatible with restorative practices, such as zero-tolerance policies in which exclusionary discipline must be applied whenever students engage in certain conduct. For schools that employ school resource officers (SROs), these staff are also key players in cultural transformations, as SRO presence is associated with more exclusionary discipline and can negatively impact school climate for student groups who experience exclusionary discipline at higher rates. As with other school staff, trainings for SROs may help mitigate some of these challenges and better enable SROs to enact restorative practices.

Developing staff mastery. Restorative programming often fails to shift school practices, in part because staff sometimes express hesitation to adopt restorative practices. Research suggests that professional development may be more effective if provided to teachers who opt in to restorative practices training. Staff buy-in may also be achieved via proactive discussions, early trainings, and psychological incentives. For example, schools can use social signaling, encouraging teachers to conduct community-building circles by providing them with opportunities to publicly display how many community-building circles they have conducted. Finally, preparing leaders for “fallback” moments, when temporary setbacks tempt staff to abandon restorative practices, can help schools sustain implementation.

Ensuring students of all backgrounds gain access to restorative practices. The analyses indicated that, even within a given school, restorative practice exposure is lower for Black students and low-income students (two groups who are particularly at risk of exposure to exclusionary discipline). Exclusionary discipline disparities also impact students with learning differences. Trainings and other interventions may be powerful tools for ensuring teachers can form positive relationships and subsequently leverage restorative practices with students of all backgrounds.

Empowering sustained implementation. In some studies of restorative implementation, changes in outcomes over time (like academic performance) were “U-shaped,” meaning there are short-term declines followed by long-term gains. Institutions hoping to realize the positive impacts of restorative practices should seek (or provide) funding that is structured to support multiple years of implementation and communicate that funding is not tied to near-term results. Caregivers may also feel concern about the effectiveness of restorative practices, so opportunities for firsthand experience with restorative practices may help mitigate apprehension and garner long-term support.

Recommendations

Findings highlight the positive impacts that restorative practices have on students and schools. State, district, and school leaders can consider the following steps as they work to create systems that promote full and equitable access to restorative practices.

Replace zero-tolerance policies and punitive discipline frameworks with relational approaches. To empower schools to realize a restorative culture shift, states, districts, and schools should shift away from zero-tolerance and punitive frameworks so that exclusionary discipline is not a default.

Incorporate indicators of exclusion, restorative practices, and school climate into continuous improvement and accountability systems. A first step for state leaders seeking to ensure all students have access to restorative practices is to incorporate suspension rates, which are readily available, into state accountability systems. States and districts also can create measures of site climate and restorative practices that they can use as part of continuous improvement and, eventually, accountability systems. Analyses presented here indicate that, even within the same school, Black students and students from low-income families have less access to restorative practices than similarly situated peers. Data regarding differential access to restorative practices could help leaders identify districts and schools in need of support to realize equitable implementation.

Secure buy-in from school staff and community members. Establishing buy-in among staff and community stakeholders is key to the ongoing success of restorative practices. To establish strong buy-in, district and school leaders may consider tapping staff who are already interested in restorative practices as early implementers; adopting “social signaling” by allowing educators and leaders to publicly celebrate restorative practice successes; and proactively communicating the value of restorative practices—and continuously communicating progress toward full implementation—to educators, community members, and caregivers.

Invest in ongoing education and support for all staff to develop restorative mastery and to expand access to restorative practices among all students. Comprehensive training provided to all school staff—including teachers, administrators, counselors, support staff, and school resource officers—can better equip staff to more equitably and effectively implement restorative practices. To fund training and ongoing support, states and districts can leverage the Every Student Succeeds Act Title IV, Part A—the Student Support and Academic Enrichment Grant Program.

Provide long-term investment and support for restorative practice implementation. It takes time and continuous effort to fully implement restorative practices. Districts and schools hoping to realize the positive impacts of restorative practices should plan for multiyear investments in implementation support, communicate that implementation must be sustained to be effective, and provide resources and ongoing training to develop and sustain educators’ restorative practices.

Fostering belonging, transforming schools: The impact of restorative practices (brief) by Sean Darling-Hammond ;is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the author and not those of our funders.