Connecting While Disconnected: Nurturing the Relationship Between Culture, Land, and Learners

By ʻAlohilani Rogers, Kuuleianuhea Awo Chun, Chelsea N. K. Keehne, and Liezl Houglum

This post is part of LPI's Learning in the Time of COVID-19 blog series, which explores evidence-based and equity-focused strategies and investments to address the current crisis and build long-term systems capacity.

Hawaiians are very familiar with the devastating impacts of pandemics. During the islands’ first century of Western contact, whooping cough, influenza, smallpox, and other epidemics created catastrophic population collapse, traumatically disrupting Hawaiian cultural continuity. Hawaiian-focused charter schools (HFCSs) were started in the early 2000s with the express purpose of creating the opportunity for students to learn ʻike kūpuna (ancestral wisdom). In contrast to the majority of Hawaiʻi’s statewide public school system, HFCS pedagogy is grounded in Hawaiian culture and purposefully builds Hawaiian identity. Students’ relationships with and responsibility for natural environments are important components of the systemwide HFCS Vision of the Graduate and are foundational to curricula, instruction, and assessments.

Today, faced with the current pandemic and the necessary shift to distance learning, educators with the HFCSs have adapted their practices to retain their rich instruction, grounded in Hawaiian culture and the natural environment. While nothing can replace the ocean voyages, agricultural work, and community service activities that are central elements of a typical school year, staff have developed new virtual ʻāina-based (land-based) activities and assessments to respond to the new reality of distance learning.

The word ʻāina, which means land, illustrates the reciprocal relationship Hawaiians have with land.

ʻĀina is their ancestor, teacher, source of cultural practices, and core to their identity.

“A ʻōlelo noʻeau” (Hawaiian proverb), conveys Hawaiian’s deep reverence for ʻāina:

He aliʻi ka ʻāina, he kauā ke kanaka

The land is a chief, man is its servant

Adapting to the New Environment

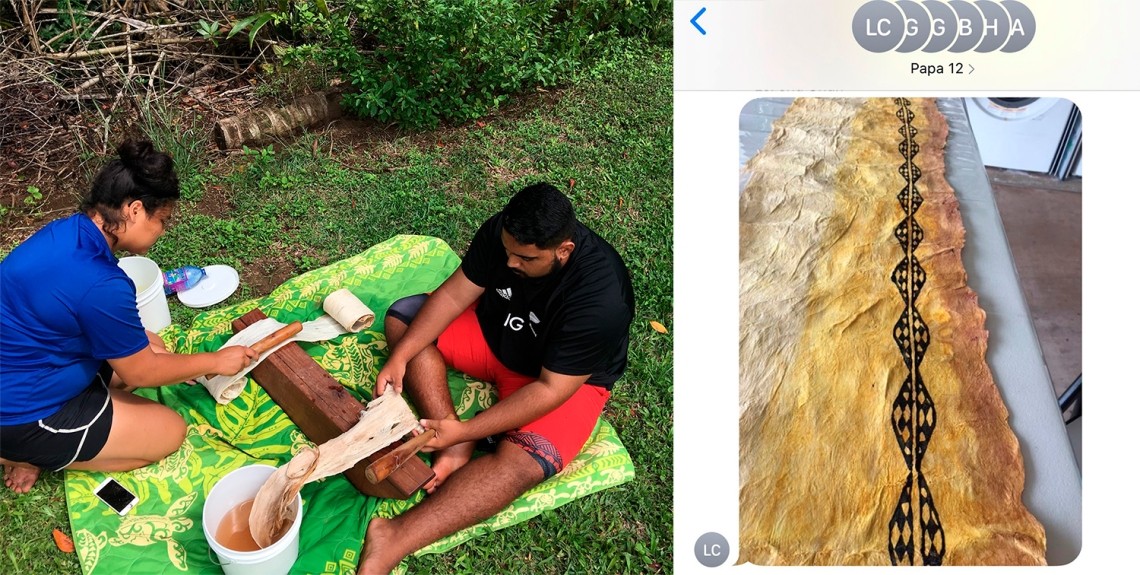

In a typical school year, each senior at Kawaikini—a k–12 HFCS school on the island of Kaua’i—creates their own kīhei. These traditional bark-cloth shawls symbolize the knowledge students have acquired and are tied over one shoulder at graduation as a rite of passage to adulthood. Although work on the shawls began before distance learning, final preparation needed to be modified to fit the new circumstances, including using acrylic paint instead of traditional plant-based materials.

Traditionally, kīhei making occurs in a face-to-face group setting, so students used FaceTime to ensure that the relationship between land, artifacts, and kanaka (man) could continue. Seniors also composed the text and melody for an oli koʻihonua, a genealogical chant, in the Hawaiian language to honor ancestors and connections to land. They drafted the text of their chants and crafted accompanying melodies. During the first few weeks of quarantine, students submitted videos of their oli koʻihonua to teachers and esteemed kumu hula (hula experts) from their community for feedback on their chanting skills.

In addition to college and career readiness, HFCSs value cultural and community readiness. To that end, senior projects at Kawaikini include a 10-page paper that addresses an issue of interest in a student’s community. One student’s project explored youth suicide prevention and focused on the research question, “How do we build resilience in youth through ancestral knowledge and cultural grounding?” This topic became particularly important and timely when COVID-19 arrived in Hawaiʻi with devastating consequences.

As the school year progressed, COVID-19 travel restrictions crippled Hawaiʻi’s tourism industry, and the unemployment rate spiked to 22%, the third-highest in the nation. A survey in April by the State Department of Health revealed that 57% of households in Kaua’i included at least one member who had lost his or her job. Suicide rates on the island increased at an alarming rate. In May, this senior was invited to participate in a virtual panel and share her research on youth suicide prevention with mental health professionals, including her finding that “cultural values and ancestral-based workshops can build resilience and self-worth.”

Cultural Competencies Ground ʻĀina-Based Education

HFCSs use the kupukupu fern as a metaphor to encapsulate the HFCS Kupukupu Framework that grounds ʻāina-based instruction and assessment. Culture is the foundation and root system from which the competencies grow. The stems and young growth that sprout through the soil represent academic learning enriched by cultural perspectives. The leaves and spores represent the manifestation and perpetuation of cultural knowledge.

The three competencies, Hōʻike (to show, demonstrate, make known), Kukupu (to grow), and Kūauhau (genealogy, traditions), are part of one fern.

- Hōʻike Performance Assessments require students to demonstrate readiness for the next level of understanding through oral presentations, portfolio defenses, and/or songs.

- Kukupu Academic Assessments allow students to demonstrate problem-solving, analysis, and application of past values in the present through essays, science labs, and/or reflections.

- Kūauhau Cultural Artifact Assessments showcase ʻike kūpuna (ancestral wisdom) in the form of genealogy, dances, chants, and/or implements. These practices were passed down for generations, are relevant to students in the present, and help prepare them for their future.

New Assessment Design

Many HFCS leaders viewed school closures as an opportunity to create new assessment systems and worked with teachers to make sure they had the support needed to implement them. For example, at Mālama Honua HFCS on O’ahu, a Modified Learning Foundation document outlines how the school’s mission, its Mind of the Navigator Skills student outcomes, and HFCS Cultural Competencies would continue to be the cornerstones of online curricula and instruction. The school’s administration met regularly with teachers and used the school’s philosophy as the foundation for schoolwide distance learning planning and decision-making.

The k–2 project, for example, asked students to answer the driving question, “What kuleana do kanaka have to to mālama uka?" (What is my responsibility to care for the mountains/ocean resources?) In an effort to support online project completion, the three HFCS Cultural Competencies were organized into smaller sections for review, creation, and reflection. K–2 Trimester Three Virtual Project packets and timelines provided a guide for teachers and students, and weekly online small-group instruction scaffolded understanding.

During the review portion, instruction focused on activating students’ prior knowledge about uka and kai ʻāina. Thinking Maps helped students to recall previously learned cultural and environmental concepts and facts. Discussion and writing prompts asked students to think about the past and share examples of how our ancestors cared for the mountains. One second-grader responded, “They took only what they needed, oli (chanted) for permission, probably didn’t litter, cleaned up the streams, planted gardens, and used plants for medicine.”

The project’s creation phase required students to design a project plan demonstrating understanding of cultural and academic content through art, hands-on projects, and song or chant writing. The final reflection phase of the project included a written reflection in which each student described how his or her project positively impacted and helped build a reciprocal relationship with the land. A second-grader reflected, “I am living mālama by taking care of ʻōhiʻa and other plants in my yard. I know that if I take care of the ʻāina then it will take care of me.”

The Land Is a Chief, Man Is Its Servant

Much like kīpuka—flourishing old-growth forests that were left unharmed as lava inundated surrounding areas—HFCSs offer students and educators rich environments where they can thrive. COVID-19 inspired creative solutions from HFCS leaders and teachers to continue to serve as kīpuka for students, families, and communities. Members of the HFCS community continually express how belonging to ʻāina is foundational to learning from and serving ‘āina. As an HFCS teacher shared, “How can we care for a place if we have never visited it, if we do not intimately know and understand it?”

With community partners and families, HFCSs have found new and innovative ways to connect students to ʻāina. Through modifying existing assessment systems for distance learning and developing new virtual ʻāina-based instruction, HFCSs remained rooted in nurturing the relationship between land and people: He aliʻi ka ʻāina, he kauā ke kanaka.

ʻAlohilani Rogers is the Cultural Education Specialist at Kawaikini Hawaiian-focused charter school, Kuuleianuhea Awo Chun is the Assistant Director at Mālama Honua Hawaiian-focused charter school, Chelsea N. K. Keehne is the Network School Liaison at Kamehameha Schools, and Liezl Houglum is the Principal Research Associate for Hiʻialo at Kamehameha Schools.