A World of Hardship: Deep Poverty and the Struggle for Educational Equity

This post is part of LPI's Learning in the Time of COVID-19 blog series, which explores evidence-based and equity-focused strategies and investments to address the current crisis and build long-term systems capacity.

One day you get out there and actually see where the children you serve on a daily basis come from. Several teachers came back after delivering food and broke down in tears telling me what they saw. A student was living in a home with no roof; they’ve got a tarp for a roof kept on by bricks and tires. Homes didn’t have doors.—Principal of a rural high-poverty elementary school

As this quote powerfully conveys, families living in deep poverty face profound material, social, and emotional hardships. Households in deep poverty suffer from food shortages, unemployment, unstable housing, inadequate medical care, electrical shutoffs, and isolation.

Children living in households in deep poverty are often “invisible” to more affluent community members—and likely to many educators as well. Too often, the plight of students living in deep poverty is subsumed under the broad definition of poverty, which does not reveal the unique hardships that are endured by those families and children with virtually no material resources. For those of us who believe in educational equity, making the invisible visible is the first step in overcoming deep disadvantage.

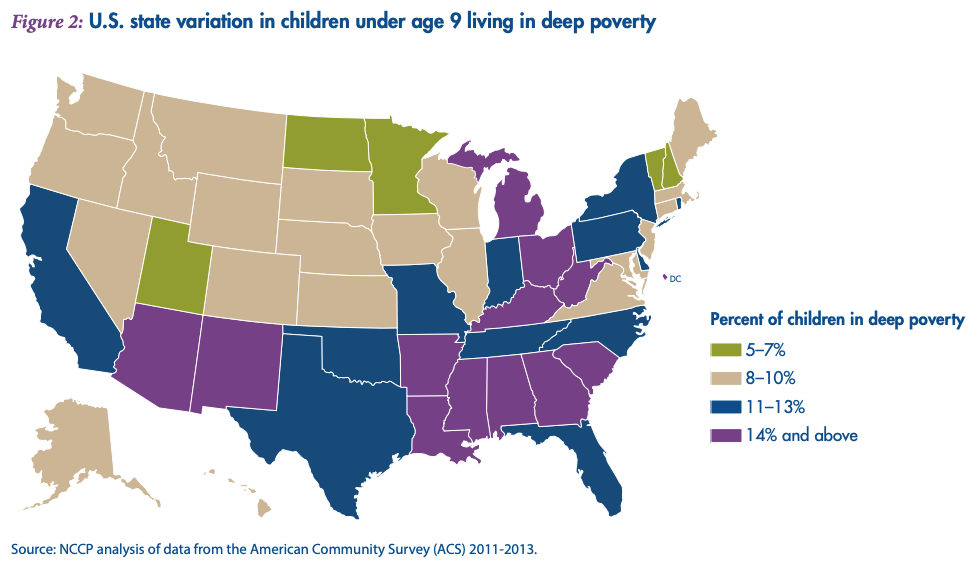

The U.S. Census Bureau defines deep poverty as living in a household with total cash income that is below 50% of the poverty threshold. As the National Center for Children in Poverty map below indicates, no state is without children living in deep poverty. Although the percentage varies considerably across states, all states have at least 5% of their children living far below the poverty line. In total, more than 5 million children in the United States live in deep poverty, including nearly 1 in 5 Black children under the age of 5.

With the explosion of the health and economic crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, households living in deep poverty have been pushed to the edge of survival: Nearly 4 in 10 Black and Latino households with children are struggling to feed their families. These numbers will no doubt grow as job losses mount, as do the numbers of children and adults of color who are contracting—and, in a disproportionate number of cases, dying from—COVID-19.

Why Deep Poverty Matters for Educators

Recently, Stanford researcher Sean Reardon and his colleagues conducted a national study on racial segregation and achievement gaps. In describing the findings he noted, “While racial segregation is important, it’s not the race of one’s classmates that matters, per se. It’s the fact that in America today, racial segregation brings with it very unequal concentrations of students in high- and low-poverty schools.” Another recent study of poverty and its effects on learning determined that levels of poverty matter in the abilities of students to succeed in school. According to the authors, “The experiences of children living in families with incomes just below the poverty line are likely quite different from those living in extreme poverty. Parents’ struggles to provide sufficient food and shelter for children may affect child academic achievement.”

The authors go on to note that the “depth of the poverty” matters both for the day-to-day life of students and families, and for public policy. “To determine appropriate subsidy levels and the types of services needed by children and families, policymakers need detailed data about the depth of family poverty. Studies have shown that simply classifying people as ‘in poverty’ or ‘not in poverty’ is not sufficient. The diversity in access to economic resources due to the depth of poverty helps explain the gaps in family investment in children’s education.”

The impact of poverty on children’s ability to learn is profound and occurs at an early age. A recent study of the neurological effects of deep poverty on young children’s development found that “poverty is tied to structural differences in several areas of the brain associated with school readiness skills, with the largest influence observed among children from the poorest households…. As much as 20% of the gap in test scores could be explained by maturational lags in the frontal and temporal lobes.” These effects were found to be associated with the consequences of living in deep poverty at an early age, some of which include premature and low-birthweight babies; poor nutrition and living without sufficient food; exposure to toxins, such as lead paint or contaminated drinking water; and lack of access to early learning opportunities.

If we are to educate the whole child, regardless of their family’s income, it is essential to provide an array of academic and social services that ensures that equity of opportunity reaches those students living in deep poverty.

The Importance of Accurately Determining Eligibility for Increased Services

In May 2020, the Learning Policy Institute published Measuring Student Socioeconomic Status: Toward a Comprehensive Approach. This report analyzes the limitations of the current methods used by school systems for measuring students’ socioeconomic status for purposes of allocating resources to meet their needs. Noting the limitations of determining a student’s level of poverty by her or his eligibility for free and reduced-price lunch—even when this measure is enhanced through direct certification of eligibility for other poverty-related programs—the report concludes that the development of new student poverty measures is urgently needed.

Blog Series: Learning in the Time of COVID-19

This blog series explores strategies and investments to address the current crisis and build long-term systems capacity. View all blogs >

The report also notes that researchers have suggested alternative measures of student poverty, some of which include parental education, student mobility, and community income as proxy measures. These strategies, however, do not appear to be capable of capturing the depth of an individual student’s poverty with the accuracy required to create and maintain academic and social programs designed and funded to meet the needs of students living in households in deep poverty. A more robust, reliable, and valid measure of students experiencing deep poverty is needed.

For several years, researchers at the Bendheim-Thomas Center for Research on Child Wellbeing at Princeton University have felt the pressing need to “move beyond income-based measures of poverty, ” according to Center Co-Director Kathryn Edin. She and her colleagues are currently utilizing measures of hardship that are more likely to reveal depth of poverty beyond income measures alone.

While there are a number of measures that identify deep poverty, perhaps the most direct, reliable, and valid measure available is a survey of a household’s ability to take care of the basic necessities of life. Households in deep poverty regularly experience food and housing insecurity, often can’t pay their bills, and are unable to access health care when they need it. At a time when access to the internet is essential for a student’s ability to learn online, families living in deep poverty often have their electricity shut off for lack of payment.

One of the most valid and reliable of these “material hardship” types of surveys has been used by the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) and, later, the Fragile Families Challenge. Material hardship measures ask direct questions about forgone consumption—that is, what families have had to do without when they may have to live on as little as two dollars a day.

Generally, surveys of material hardship consist of 10 or more questions. Below are some of the types of questions that might be included in a school-based survey to better understand the day-to-day realities for students and families:

- In the past 12 months, were you ever hungry, but didn’t eat because you couldn’t afford enough food?

- In the past 12 months, did you move in with other people even for a little while because of financial problems?

- In the past 12 months, was there anyone in your household who needed to see a doctor or go to the hospital but couldn’t go because of the cost?

- In the past 12 months, did you receive free food or meals?

- In the past 12 months, did you not pay the full amount of a gas, oil, or electricity bill?

These measures do not replace income measures; they supplement them in order to get a fuller understanding of the lived experience of families living in deep poverty. For example, as a supplementary measure, a survey of material hardship could be incorporated into the free and reduced-price lunch forms sent to families to determine their eligibility to receive meals at school. When the material hardship surveys are returned, school administrators would have a clear indication of which students are living in deep poverty.

This recommendation can be seen as a first step in a more comprehensive approach to measuring deep poverty of students. Undocumented or mixed-status families might hesitate to complete government forms for fear of deportation; some families might not complete the material hardship survey due to privacy or other concerns. Some of these concerns could be addressed in community school settings, where the ties between families and the school are often close and continuous. The establishment of trust is a bond that can help to overcome the fear of government.

More From the Blog Series

To some busy school administrators, adding any survey might seem burdensome, but the returns on a short material hardship survey are very high. With this information, schools and school systems will be able to tailor programs to meet the needs of children and young adults living in families in deep poverty. These programs should support students’ health and well-being, as well as include academic enhancement and enrichment. In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, waiting for the perfect measure could result in increased hardship for students trapped in deep poverty.

Toward Educational Equity

Since the 1990s, the social safety net has been basically shredded. As a result, in many communities, the local public school system is often the only entity situated to meet the needs of students from families in deep poverty by providing meals as well as a safe place to be during the day. Early intervention programs, such a free and high-quality early childhood programs, are a very promising approach to mitigating the effects of deep poverty on young children. Community schools, which provide students and families with a range of supports and services to mitigate the impact of deep poverty—from health and mental health care to before- and after-school care and social service supports—are another promising example. Ensuring that these services are available to children in deep poverty can literally mean the difference between life and death—and between a chance in life and none—for many of these young people.

These are just two examples of how information about students’ level of poverty can lead to improved and expanded services and supports to meet their needs. Of course, schools alone cannot reverse the impact of deep poverty on children, families, and communities. But without well-financed schools with the targeted resources needed to enable students’ learning, the negative effects of deep poverty on children will remain, now and in the future.