Improving Education the New Mexico Way: An Evidence-Based Approach

Following a major court decision requiring more adequate and equitable school funding in New Mexico, state leaders and stakeholders have begun to reimagine the system of education. As part of this process, the Learning Policy Institute was asked to conduct research on the challenges facing education in the state and to identify evidence-based policies that could build a high-quality, equitable system able to provide a culturally and linguistically responsive education for the state’s diverse learners.

This study has yielded a set of recommendations that are evidence-based, locally informed, and resonant with the goals of New Mexicans. It focuses on five fundamental elements of a high-quality education system: meaningful learning, knowledgeable and skillful educators, integrated student supports, and high-quality early learning opportunities, and adequate and equitably distributed school funding.

The authors describe how the state can center the design of its educational system on the diverse needs of its students of color and students from low-income families, who represent most of the state’s population, rather than placing them at the periphery where they might get “special” help. Noting that "this is not short-term work" that can be done within conventional political cycles or by any single entity, the authors developed the report as a road map to help all New Mexico stakeholders focus on long-term improvement as the state recovers from COVID-19 setbacks. For the near term, they also address what can be done without a large infusion of new funds.

Background

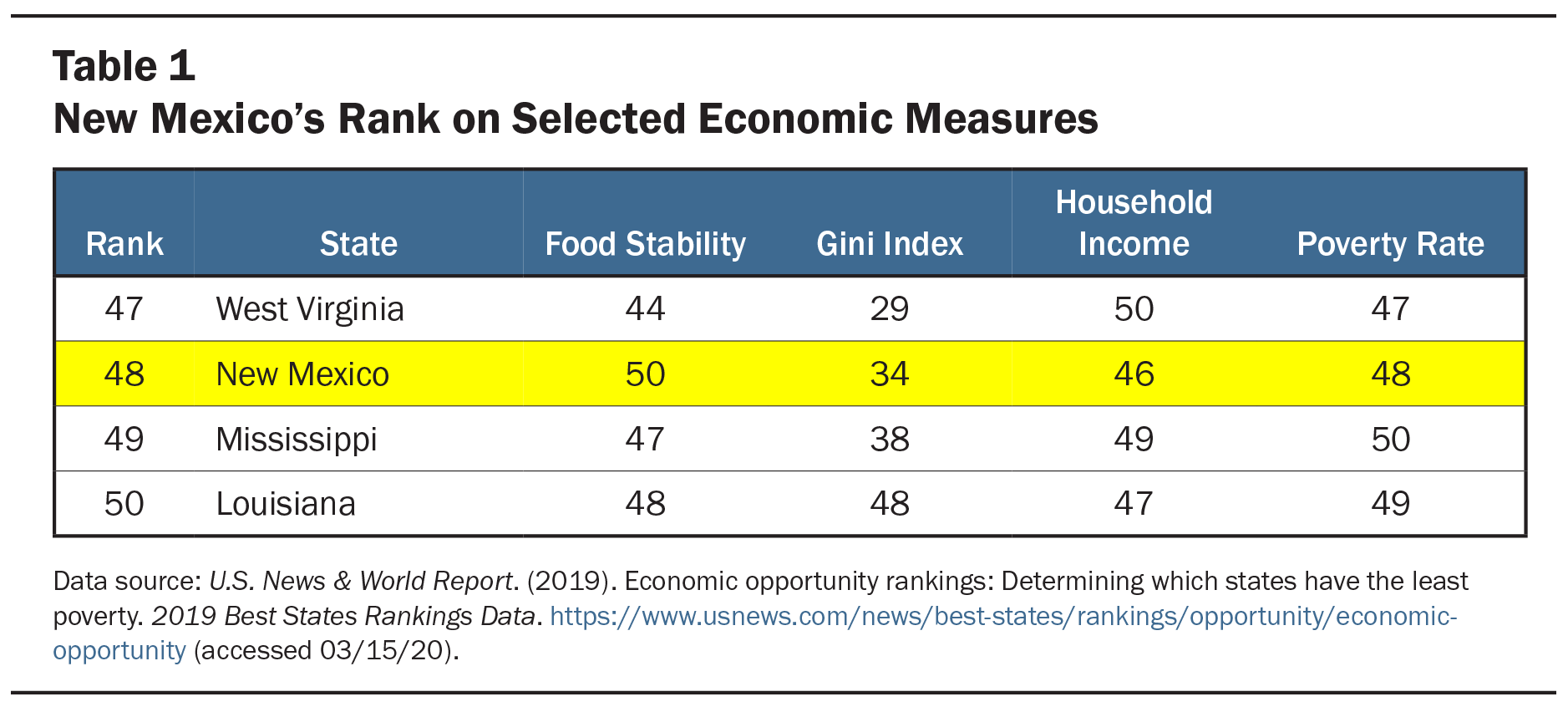

New Mexico’s education system operates in a social and economic context that has been unable to lift a large proportion of the state’s young people out of poverty or ameliorate the barriers that poverty creates to school success. In 2018, 75% of New Mexico’s students qualified for federally subsidized meals because of their families’ low incomes. More than 1 in 10 children (13%) lived in extreme poverty (i.e., families with incomes that were less than half of the federal poverty line), and 35% lived with families in which no parent had secure employment. A quarter lived in households that were food insecure, and 37% lived with families receiving public assistance. Twelve percent of New Mexico teens between 16 and 19 were neither in school nor working. The U.S. News & World Report ranking of New Mexico as 48th among the states in economic opportunity is illustrative of the state’s relative deprivation. This measure includes the households living below the federal poverty line, along with food insecurity, household income, and the disparity of income between the lowest-income households and the highest (using the Gini index) (see Table 1).

Together, the Office of the Governor, the New Mexico Legislature, advocates, and educators have begun making progress toward a stronger system—increasing teacher compensation, providing for expanded learning time in high-poverty schools, launching a new statewide community schools initiative, and moving toward a useful and supportive accountability system, to name just a few steps in the right direction.

The current moment is precarious, however. The coronavirus pandemic, which closed schools for one third of the 2019–20 school year, is also damaging the state’s economy—made worse by the related plunge in oil prices and the collapse of tourism. The state has already made cutbacks to education funding, as well as to other social and economic supports. At the same time, evidence that the state’s most at-risk children are experiencing the most dire effects of closed schools, job losses, and declines in state revenue brings into even sharper relief the combined harms of poverty and lack of access to good schooling in New Mexico. For example, a recent national study estimated that 56% of the state’s Native households with children under 18 (nearly 15,000 children) lack access to broadband required to make remote learning possible, and 34% of Native households with children (19,250 children) have no computer. The study also estimated that more than half of New Mexico households making less than $25,000 per year (with more than 59,000 children) lack sufficient internet, and 32% of such households (with more than 34,000 children) are without a computer. In 2020, New Mexico ranked 49th among states in the percentage of households with sufficient broadband access.

This challenge may be more daunting in New Mexico than it is in states with stronger economies and less poverty, but New Mexicans are ready for change: In summer 2019, only 29% of New Mexicans rated the current system to be either “excellent” or “good.” More than half recognized that out-of-school factors such as poverty pose serious problems for the education system. More than half judged the state’s investments in education as inadequate. This report addresses both this historic moment and New Mexico’s need for a long-term plan to make fundamental, systemic improvements. It briefly lays out the status of New Mexico’s educational system, paying particular attention to how it has served those who are vulnerable. It recommends evidence-based short- and long-term changes toward a complete revamping of the system with rationality and equity. These changes would create policies, structures, and practices that both center the needs of students facing the greatest challenges and serve more advantaged students well.

For more than a year, LPI conducted research in New Mexico to provide New Mexico policymakers, stakeholders, leaders, and other interested parties a research perspective on the challenges facing education in the state and to identify evidence-based policies that could build a high-quality, equitable system. The research included:

- A review of state policy documents and analyses produced by stakeholder, research, and advocacy groups;

- interviews with more than 80 key stakeholders; and

- new statistical analyses of data from the New Mexico Public Education Department database and publicly available data.

This research, together with numerous national and international studies, yielded recommendations that are evidence-based, locally informed, and resonant with the goals of New Mexicans.

The most critical finding from the research is that key to education improvement is recognizing that children and young people who face barriers to school success from poverty and marginalization are the norm in New Mexico, rather than exceptions. Accordingly, the state must design its educational system with their diverse needs at the center, rather than placing them at the periphery where they might get “special” help. That means developing, adopting, adequately resourcing, and implementing education policies, structures, and practices that both foster high levels of meaningful learning and counterbalance the out-of-school barriers most New Mexico children face. Such an approach aligns with the state’s pledge—already established in statute—that “no education system can be sufficient for the education of all children unless it is founded on the sound principle that every child can learn and succeed.”

This report provides a road map to help New Mexico leaders focus on long-term improvement as the state recovers from COVID-19 setbacks. It focuses on system changes at the state level that can enable and support local improvement across New Mexico’s diverse communities and schools. For the near term, we identify what can be done without a large infusion of new funds. State policymakers, together with leaders from education, business, nonprofits, and tribal governments, can draw on recommendations in this report as they work to create a coherent post- COVID-19 approach to deep and lasting improvement in New Mexico schools.

This is not short-term work. Even in good times, it cannot be done within conventional political cycles, and it must be protected from the vagaries of political transitions. It is also not work that can be done by policymakers without transparency and significant engagement of educators, community members, and other stakeholders. The transformational change necessary is simply too large to be addressed by any single entity.

Ideally, the long-term agenda can be overseen by leaders in New Mexico’s public, private, and tribal sectors who come together as an independent, bipartisan statewide advisory group or “commission,” as has worked well in other locales.

What Can Be Done Now? Focus on Five Fundamental Elements of a High-Quality Education System Supported by a Thoughtful Accountability System

Although New Mexico has unique challenges that must be met, states and nations that have improved education effectively have strengthened five common and fundamental elements of their systems:

- Meaningful learning goals, supported by

- Knowledgeable and skillful educators,

- Integrated student supports,

- High-quality early learning opportunities, all made possible with

- Adequate and equitably distributed school funding.

Making policy changes in all five is possible in New Mexico and could bring significant improvement. As necessary as policy changes in these five elements are, they are not enough to bring significant improvement. In addition to adopting productive policies, every high-performing system has developed a thoughtful accountability system that focuses attention on the right actions at the state and local levels by providing data on what matters for opportunity and outcomes and by developing capacity to implement policy well.

How Can New Mexicans Move This Agenda Forward?

Education system improvement is not quick work. It takes comprehensive learning and change, championed by those both in and outside the current system. This is more the case than ever as New Mexico confronts the challenges from the coronavirus pandemic. Ideally, as has been the case in several other states, a bipartisan and diverse cadre of leaders of New Mexico’s public and private sectors can be brought together as an independent statewide commission or task force to assume responsibility for articulating this agenda by setting specific goals and timelines for developing collective and sustained ownership and by leading the state toward a system that complies with the court order in Martinez/Yazzie v. State of New Mexico because it works for all New Mexico children.

Improving Education the New Mexico Way: An Evidence-Based Approach by Jeannie Oakes, Danny Espinoza, Linda Darling-Hammond, Carmen Gonzales, Jennifer DePaoli, Tara Kini, Gary Hoachlander, Dion Burns, Michael Griffith, and Melanie Leung is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported in part by the Thornburg Foundation. Additional support came from the Learning Policy Institute’s core operating support from the Heising-Simons Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.