Learning to Lead: Understanding California’s Learning System for School and District Leaders

Summary

Based on a survey of California principals and interviews with superintendents, this study examines professional learning experiences for the state’s school leaders. We find that California’s education leaders experience elements of high-quality preparation, with significantly better initial training reported by the state’s new principals. However, most principals’ learning opportunities are piecemeal and often do not include the elements principals most value. Access to professional learning is especially poor for principals in rural areas. The state’s educational leaders do not consistently participate in professional learning opportunities that support them in leading schools that develop students’ deeper learning and social and emotional competencies. They do, however, want more of it.

Few would dispute that improving student achievement in California requires strong school and district leadership. Well prepared and supported educational leaders are pivotal under the state’s new policy direction, which emphasizes local decision making for budgeting and includes new initiatives related to curriculum, instruction, and accountability. These reforms call for leaders who can guide change processes that push toward more meaningful 21st century learning that supports students’ academic, social, and emotional development. Yet within this context of far-reaching education system reforms, investment in the growth of educational leaders has so far been an overlooked course of action.

To help remedy this, the Learning Policy Institute—with the assistance of the Association of California School Administrators and the American Institutes for Research—took the foundational step of conducting a study aimed at understanding the strengths, weaknesses, and needs of preparation and professional development for the state’s educational leaders.

We administered a representative survey of more than 450 California principals; analyzed the most recent federal data about school leaders in California and across the nation; reviewed available California data; and conducted focus groups and interviews with principals, former principals, and superintendents from across the state. Reporting on that study, this summary

- provides an overview of California’s leadership context,

- describes the kinds of principal preparation and professional development available in the state,

- reports how prepared principals feel to lead in light of the new educational demands of deeper learning and supporting the whole child,

- summarizes the learning opportunities principals report they want,

- describes superintendents’ experiences with professional learning, and

- offers policy considerations informed by our findings.

Why Invest in Leaders’ Learning?

Multiple studies find that increased principal and superintendent quality is associated with gains in student achievement, even when controlling for student and school characteristics.Béteille, T., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2012). Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes. Social Science Research, 41, 904–919; Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2012). Estimating the effect of leaders on public sector productivity: The case of school principals. (Working paper). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; Coelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109; Dhuey, E., & Smith, J. (2014). How important are school principals in the production of student achievement? Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(2), 634–663; Grissom, J. A., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2015). Using student test scores to measure principal performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 3–28; Miller, A. (2013). Principal turnover and student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 36, 60–72. And strong school and district leadership is particularly important as California is implementing new educational initiatives that expect schools to provide learning experiences that emphasize students’ abilities to apply knowledge to novel, interdisciplinary problems, and to engage in rigorous, self-directed inquiry. In addition, schools are increasingly supporting social and emotional learning, including the ability to collaborate and make responsible decisions, as well as the acquisition of productive mindsets and habits, such as thinking positively about how to handle challenges and coming to class prepared. Importantly, leaders need to be able to orchestrate the sustained collaborative efforts needed to make the instructional shifts these reforms necessitate.

Being able to successfully make these educational shifts requires substantial expertise on the part of superintendents and principals. Moreover, due to widespread teacher shortages, the ability of school leaders to create the positive working conditions and collaborative, supportive environments that retain teachers plays a critical role in mitigating shortages.Sutcher, L., Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2018). Understaffed and underprepared: California districts report ongoing teacher shortages. (Research brief). Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Despite the clear importance of quality leaders, California is failing to provide the support sufficient to help them develop expertise and keep them on the job. Every one of the 15 superintendents interviewed in our focus groups reported a shortage of quality principals in their district. Overall, our study found high rates of turnover and inexperience—a particular concern for the principalship, since research demonstrates that it takes time for principals to make meaningful improvements in their schools.

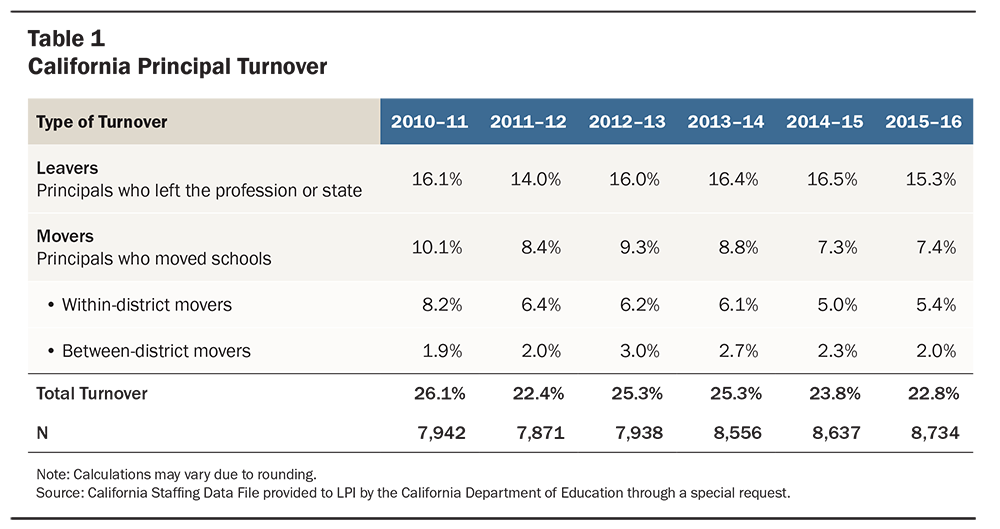

From the 2015–16 school year to the 2016–17 school year, 15% of California principals left the profession or state, and another 7% moved to a different school—meaning that more than 1 in 5 principals (23%) left their current position (see Table 1). From 2014–15 to 2015–16, 24% of principals left their positions—17% leaving the profession or state and 7% moving from one school to another.

Similarly, we found high superintendent turnover rates. Approximately 21% of superintendents left the profession or the state after the 2014–15 school year, and 13% left after the 2015–16 school year. Moreover, in those same years, another 3% and 5% of superintendents, respectively, switched districts, meaning that nearly 18% to 24% of California superintendents left their districts either because they left the profession, the state, or the district.California Staffing Data File provided to LPI by the California Department of Education through a special request.

Compounding the turnover challenge, California’s principals tend to have less experience than those in many other states. The modal (most common) principal in the state has just 1 year of experience at his or her own school, accounting for over 1 in 5 principals.Learning Policy Institute. (2017). Survey of California Principals. Similarly, superintendents appear to lack experience. A study of 215 California superintendents found that 45% left their current positions after 3 years,Grissom, J. A., & Andersen, S. (2012). Why superintendents turn over. American Educational Research Journal, 49(6), 1146–1180. in keeping with findings from a nationwide survey that the most common superintendent had between 1 and 5 years in his or her current position.Finnan, L. A., & McCord, R. S. (2017). AASA salary & benefits study. Alexandria, VA: AASA The School Superintendents Association.

What Kinds of Preparation and Professional Learning Are Available to California Principals?

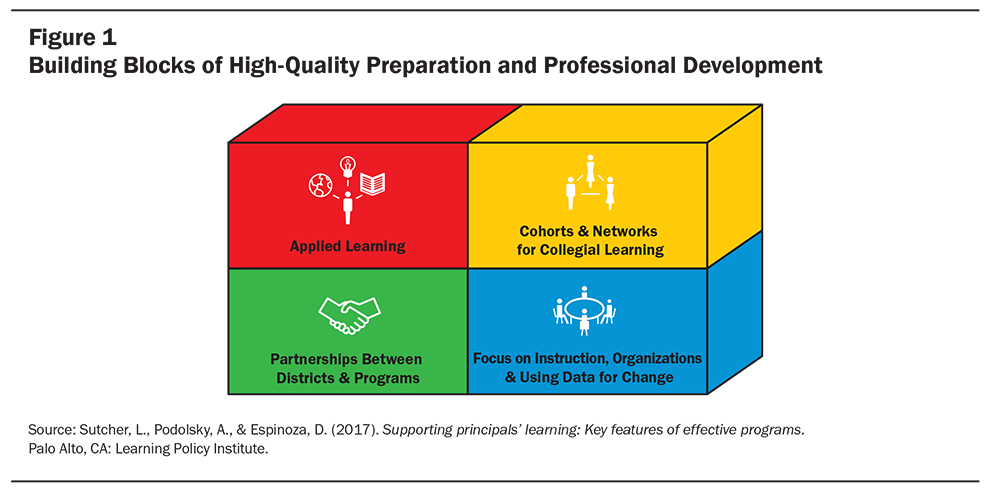

Research on high-quality principal preparation and development for school leaders finds that these experiences are often comprised of the following building blocks:Sutcher, L., Podolsky, A., & Espinoza, D. (2017). Supporting principals’ learning: Key features of effective programs. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

- strong partnerships between the district and the leadership program;

- collaborative structures that train and support educational leaders, such as cohorts and networks of program participants;

- problem-based applied learning methods, field-based internships, and on-the-job coaching by an expert principal or superintendent; and

- a focus on supporting leaders in learning how to improve schoolwide instruction, support collegial teaching and learning environments, and analyze and act on data (see Figure 1).

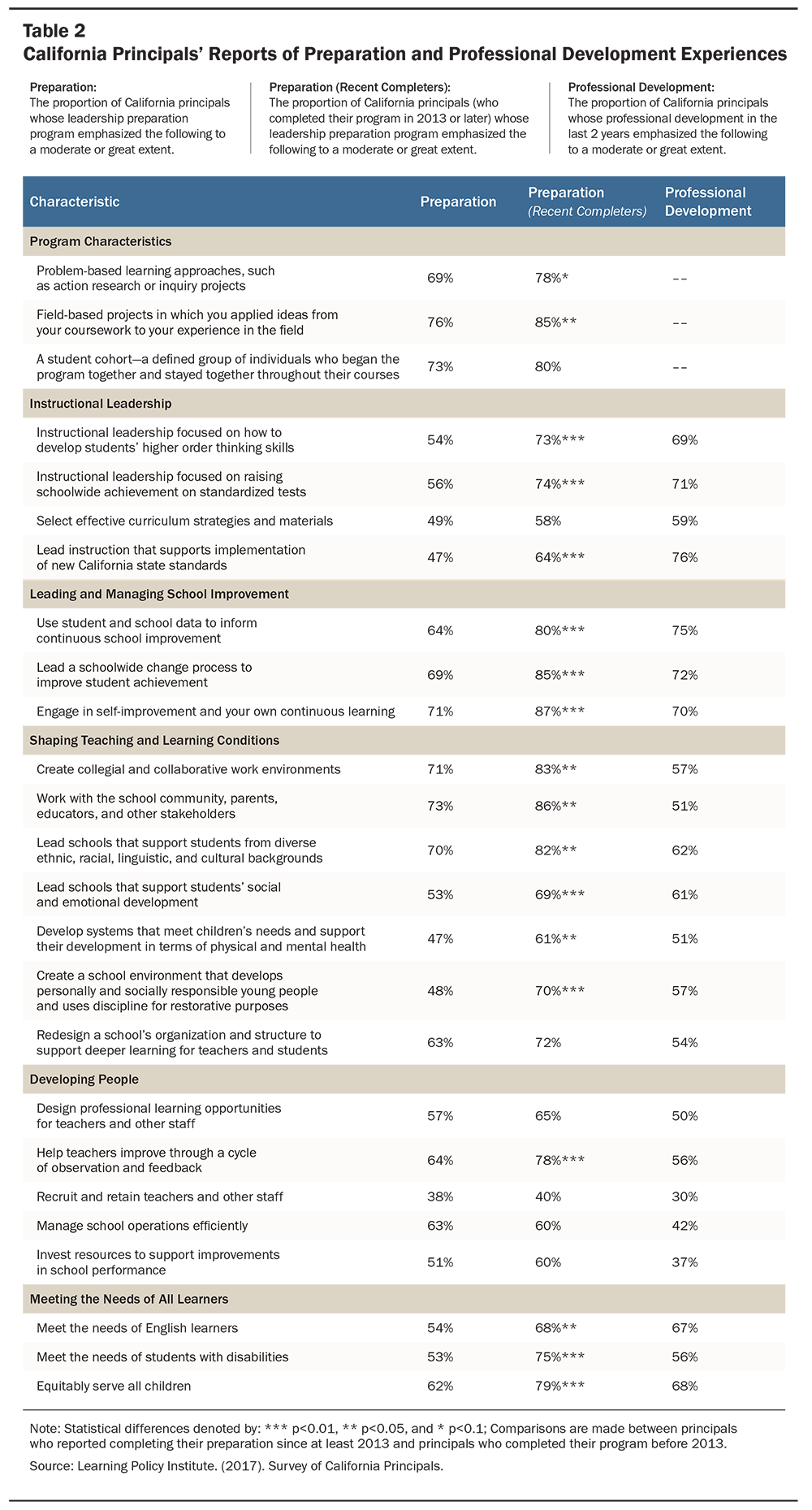

The results from our 2017 survey of more than 450 principals provide insight into California principals’ preparation and professional development experiences. Significantly, more than half of California’s principals report preparation and professional development that focuses on the kind of content that research suggests is central to effective leadership (see Table 2). For example:

- Close to 3 in 4 principals who attended leadership preparation programs report that their program emphasized problem-based learning and field-based projects, at least to a moderate extent.

- California principals who have completed a preparation program recently (2013 or later) are significantly more likely to have received the high-quality features of preparation highlighted in the literature, compared with principals more generally. This finding suggests a positive trend in California’s administrator preparation system.

- About 70% of principals reported receiving professional development that covered using data to support continuous improvement, leading a schoolwide change process, and leading instruction for both increasing student achievement and developing students’ higher order thinking skills. More than 75% of principals also reported receiving professional development on the new California state standards to a moderate or great extent.

Although many principals have experienced individual elements of high-quality preparation and professional development as previously described, very few have experienced the full complement of programmatic elements associated with developing strong principals.

Only 1 in 20 California principals experienced all of the building blocks of high-quality learning in their preparation program. Moreover, a critical aspect of high-quality preparation programs is the opportunity for participants to engage in an internship and field experience in which they can practice the types of leadership activities they will need to carry out as principals. Only 60% reported receiving a supervised internship or field experience during their preparation program, defined as working directly with a principal and engaging in administrative tasks under supervision. Less than 20% reported that their internship was of a sufficient duration and frequency (i.e., over 20 weeks with mentoring from an expert at least once a month).

Among recent preparation program completers (2013 or later), more principals received a collection of high-quality preparation elements. Recent completers were also more likely to receive an internship of sufficient duration and frequency. Again, this is evidence that principals who completed their preparation program in the last 5 or so years are receiving more elements of high-quality preparation—a promising trend. However, the majority (56%) of recent completers didn’t receive comprehensive preparation.

Just over 1 in 10 California principals report having engaged in professional development in the last 2 years that incorporates the previously mentioned four research-based elements of effective learning for leaders. This suggests that approximately 90% of California principals are not receiving a comprehensive system of learning opportunities that will help them continue to grow. For principals in rural areas, access to these key professional development activities is a particular challenge.

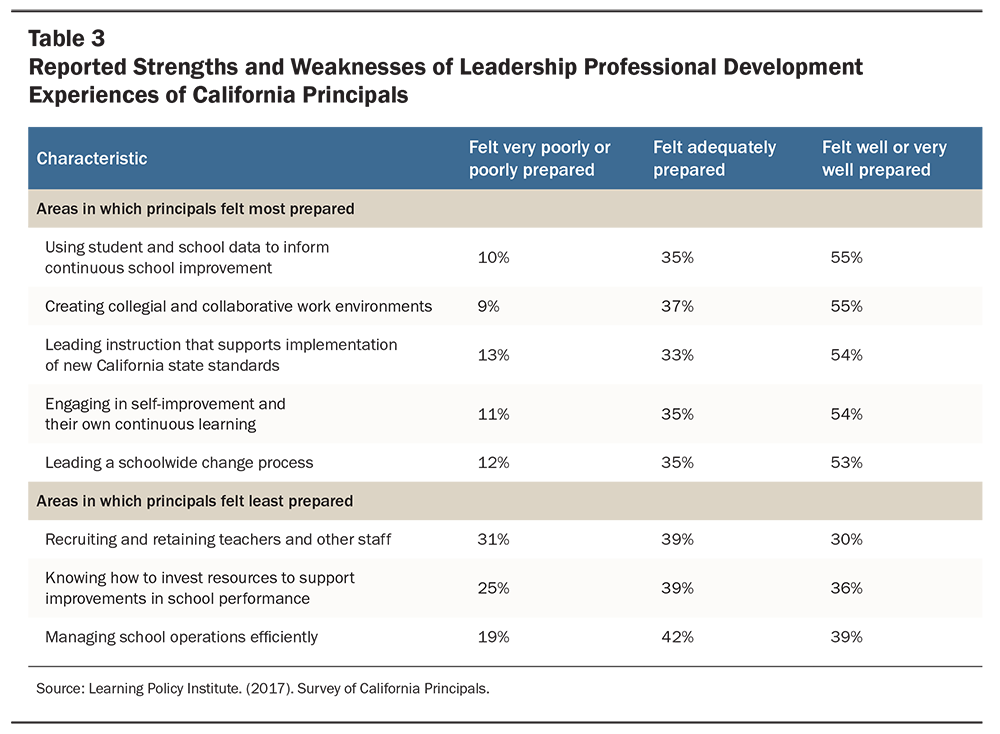

Table 3 shows the professional development topics in which principals reported feeling most prepared. These include:

- using data to inform school improvement (55% felt well or very well prepared),

- creating collegial working environments (55% felt well or very well prepared), and

- leading instruction that supports the California state standards (54% felt well or very well prepared).

Despite these strengths, our research suggests that California still has a long way to go in ensuring that principals are supported to succeed. Approximately half of principals do not feel well prepared in these areas, with 1 in 10 principals feeling poorly or very poorly prepared. And more than a quarter of principals also report feeling poorly or very poorly prepared to recruit and retain teachers. Considering that California is currently experiencing widespread teacher shortages, expanding learning opportunities around issues of attracting and keeping teachers is a clear need.

How Well Prepared Do California Principals Feel to Lead 21st Century Learning?

Quality preparation and development for principals is especially important for implementing deeper learning and whole child practices to prepare and support the next generation of citizens for today’s dynamic, knowledge-driven economy. In our survey, we defined deeper learning as follows:

- developing students’ higher order thinking skills,

- creating collegial and collaborative work environments, and

- organizing schools to support deeper learning for teachers and students.

California principals rarely receive support and learning around deeper learning competencies. Our findings show, for example:

- About 37% of principals felt their leadership preparation program covered deeper learning to a moderate or great extent; 38% rated their in-service professional development on deeper learning similarly.

- Only about 1 in 3 principals felt their preparation program or professional development prepared them well or very well to lead deeper learning.

Similarly, California principals do not receive consistent learning related to leading schools to address the needs of the whole child. In our survey, we defined these competencies to include

- supporting students from diverse ethnic, racial, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds;

- supporting students’ social and emotional development;

- meeting children’s needs and supporting their physical development and mental health; and

- developing personally and socially responsible young people and using discipline for restorative purposes.

Small proportions of principals report receiving learning support that addresses these competencies. Our findings show, for example:

- About 1 in 3 principals (32%) felt their leadership preparation program covered whole child practices to a moderate or great extent; roughly 2 in 5 (41%) rated their in-service learning on whole child practices similarly.

- Fewer than 1 in 3 principals felt their preparation or professional development activities in the last 2 years prepared them well or very well for practices fundamental to supporting the whole child.

What Learning Opportunities Do California Principals Need?

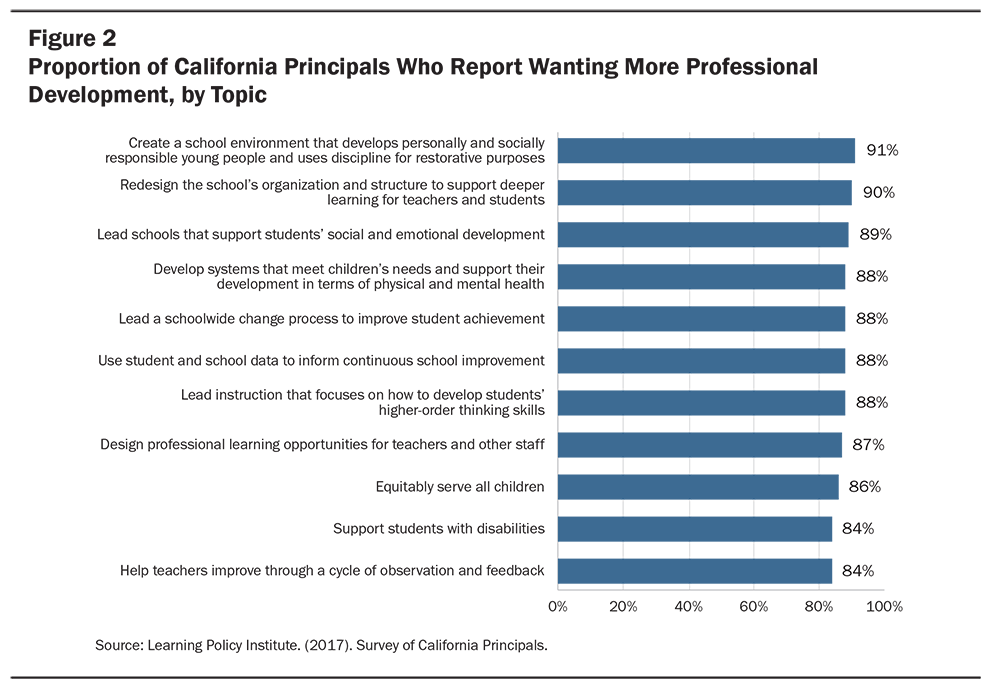

Perhaps unsurprisingly, California’s principals want more opportunities to be prepared to lead for deeper learning and support of the whole child (See Figure 2). From a list of 22 professional development topics, the top three for which principals desired additional learning are

- how to create a school environment that develops personally and socially responsible young people and uses discipline for restorative purposes (91%),

- how to redesign a school’s organization and structure to support deeper learning for teachers and students (90%), and

- how to lead schools that support students’ social and emotional development (89%).

In addition to these priorities, however, principals want more professional development across the board. Nearly all (98%) would like more professional development on at least one topic, and over 70% want more learning on all of the 22 topics listed.

Principals in schools serving higher proportions of low-income students and students of color are more likely to report wanting professional development in a variety of topics, including leading a schoolwide change process, serving students with disabilities, and leading instruction focused on students’ higher order thinking skills. Supporting on-the-job learning for principals working in underserved communities is key to better addressing the state’s persistent achievement gaps.

In addition, our survey results and conversations with principals suggest that the following types of professional development activities are most helpful:

- peer observation and/or coaching,

- participating in a principal network, and

- mentoring and coaching.

Unfortunately, some of the most helpful types of professional development, according to principals—peer observation, coaching, and mentoring—are also some of the least available, especially in rural areas.

Significant obstacles to obtaining desired professional learning are lack of time and funding. Principals report feeling penalized for time spent away from their schools or districts. One principal elaborated: “We’re not supposed to be off-site. We’re supposed to be on-site, and a lot of the [professional development or its associated collaboration] is off-site.”

The funding challenge includes covering not only the costs of professional development participation but also the costs of school oversight needed while the principal is away.

What Are California Superintendents’ Experiences With Professional Learning?

Superintendents reported that it is largely their responsibility to seek professional development experiences. As one superintendent explained:

I feel well prepared, but the preparation is of my own doing. … What is unique is that at a district level the superintendent and team provides the learning for principals and provides learning for directors and provides learning for teachers and classified staff and so forth. But there isn’t anybody above the superintendent in terms of providing that learning for us. … There are opportunities for us to seek that learning and lots of professional reading and networks among each other. But if you do not seek it out yourself, it does not come to you.

California superintendents identify several types of professional development as most important to their continued growth:

- formal and informal networks with peer superintendents,

- coaching and mentoring from seasoned superintendents,

- partnerships and coursework from institutions of higher education, and

- reading professional literature and research.

Like principals, superintendents report lack of time and funding to be significant obstacles to obtaining desired professional learning. Also like principals, superintendents feel they are penalized for time away from their districts and face challenges covering the costs of professional development participation and ensuring district oversight while they are away.

Policy Considerations

In the past, California has made significant investments in professional learning for the state’s education leaders. In particular, the California School Leadership Academy, which operated 12 county leadership centers from 1983 to 2003, was a highly effective support system for principal and superintendent learning emulated by many other states.Darling-Hammond, L., Orphanos, S., LaPointe, M., & Weeks, S. (2007). Leadership development in California. Getting Down to Facts. But earlier investments eroded over time, and for many years, there was no state investment in leaders’ professional learning.

Recently, the state has taken significant action to improve the quality of principal preparation through reforms of licensure and accreditation. It has also begun making modest investments in principals’ professional learning. But to address persistent achievement gaps and prepare California’s children for the 21st century, what’s needed is a comprehensive system of preparation and on-the-job learning for California education leaders.

To develop such a system, our research suggests the following five key policy recommendations:

- Target leadership development. Ensure that California’s emerging statewide system of support targets the professional learning of school and district leaders and rebuilds a statewide infrastructure to do so. The new investments planned for eight “lead” county offices of education could include coordinated, intensive, and sustained professional learning and support for school leaders as was once available under the California School Leadership Academy. New funds available under Titles I and II of the Every Student Succeeds Act are also available to help build this infrastructure.California Department of Education. (2017). SBE agenda for May 2017.

- Align content with needs. Align the content and structure of professional learning opportunities to the identified needs of California’s school leaders, with an emphasis on preparation for current challenges and opportunities for peer-to-peer interactions, networks, and mentoring. Principals want content that will help them redesign school structures and support instruction for deeper learning; lead instruction that focuses on higher order thinking skills; use discipline for restorative justice purposes; support students’ social and emotional development and physical and mental health; use data and lead schoolwide change to improve student achievement; support professional learning for teachers; and equitably serve all students.

- Ensure supports for new principals. Ensure that all novice school leaders have access to a high-quality and affordable induction program through strategic programmatic support. Despite state requirements for induction, we found that only 43% of first- and second-year principals had a formal on-the-job mentor or coach with whom they met at least once a month.

- Continue strengthening licensure and accreditation. Stay the course to strengthen and streamline California’s licensure and accreditation system for school administrators, including implementation of new standards, newly designed preparation and induction programs, and California’s new administrator performance assessment. Evidence suggests that recent program completers feel significantly better prepared to lead the state’s new approaches and meet students’ needs than earlier-trained principals.Learning Policy Institute. (2017). Survey of California Principals; California Department of Education. (2015). The superintendent’s quality professional learning standards.

- Build a pipeline. Build a robust pipeline of qualified and committed school principals through service scholarships and residency programs for school leaders. Like some other states, California could fund service scholarship programs to attract exemplary candidates to the field and allow them to participate in internships with expert principals—a key feature of effective programs. Districts can emulate the “grow your own” pipeline that Long Beach Unified School District has used to train and support leaders in collaboration with the local university, creating a base of strong knowledge and skills while avoiding shortages.Long Beach Unified School District. (2016). School Leadership Program (SLP) annual performance report form 1855–0019 executive summary. Unpublished manuscript.

Providing quality preparation and professional development opportunities to education leaders is critical for achieving the state’s goals, and California’s school leaders are clear that they want and need more and better opportunities to learn. As it seeks to fully implement its ambitious reforms, California should continue to build on its efforts to improve administrator preparation and develop a statewide system of ongoing learning supports for principals and superintendents. These investments are critical to the success of the Golden State’s future generations.

Learning to Lead: Understanding California’s Learning System for School and District Leaders by Leib Sutcher, Anne Podolsky, Tara Kini, and Patrick M. Shields is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The report was prepared in part for inclusion in the California Getting Down to Facts II Project and benefited from the ideas and feedback of its research team.

The Learning Policy Institute’s research in this area is supported by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation and the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for LPI is provided by the Ford Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Sandler Foundation.