Educator Learning to Enact the Science of Learning and Development

Research advances in neuroscience and the developmental and learning sciences have provided us with important insights about how people learn and develop. The knowledge we now have points to important transformations in teaching practice, which in turn require transformations in educator development in order to support all educators in developing the knowledge, skills, and dispositions associated with developing the whole child. This report synthesizes research on how to support educators in developing those capacities both in preservice and in-service contexts. It addresses both the “what” of teacher and leader preparation—the content educators need to learn about children and how to support their development and learning—and the “how”—the strategies for educator learning that can produce deep understanding; useful skills; and the capacity to reflect, learn, and continue to improve.

Foundations for Educator Preparation

Syntheses of advances from the science, linked to educational research, have identified implications for practice of the science of learning and development and a set of design principles for schools for putting the science of learning and development into action. These syntheses point to the following principles as a foundation for educators’ knowledge base:

- The brain and development are malleable across the entire life span in response to relationships, experiences, and contexts.

- Variability in human development is the norm, not the exception.

- Human relationships catalyze healthy development and learning.

- Learning is social, emotional, and cognitive.

- People actively construct knowledge based on their experiences in social and cultural contexts.

- Adversity affects learning—and the way schools respond matters.

Developing the kinds of skills currently required in a fast-changing knowledge-based society requires a different kind of teaching and learning from prior eras of education when learning was conceptualized as the acquisition of facts and teaching as the transmission of information to be taken in and used “as is.” This means students need opportunities to set goals and assess their own work and that of their peers so that they become increasingly self-aware, confident, and independent learners. To become productive citizens within and beyond the school, students also need positive mindsets about self and school, along with social awareness and responsibility.

The ability of schools to help achieve these outcomes requires environments, structures, and practices attuned to students’ learning and developmental needs. These include:

- positive developmental relationships;

- environments filled with safety and belonging;

- rich learning experiences that support deep knowledge development;

- development of social, emotional, and cognitive skills, habits, and mindsets; and

- integrated support systems.

What Do Educators Need to Know and Be Able to Do?

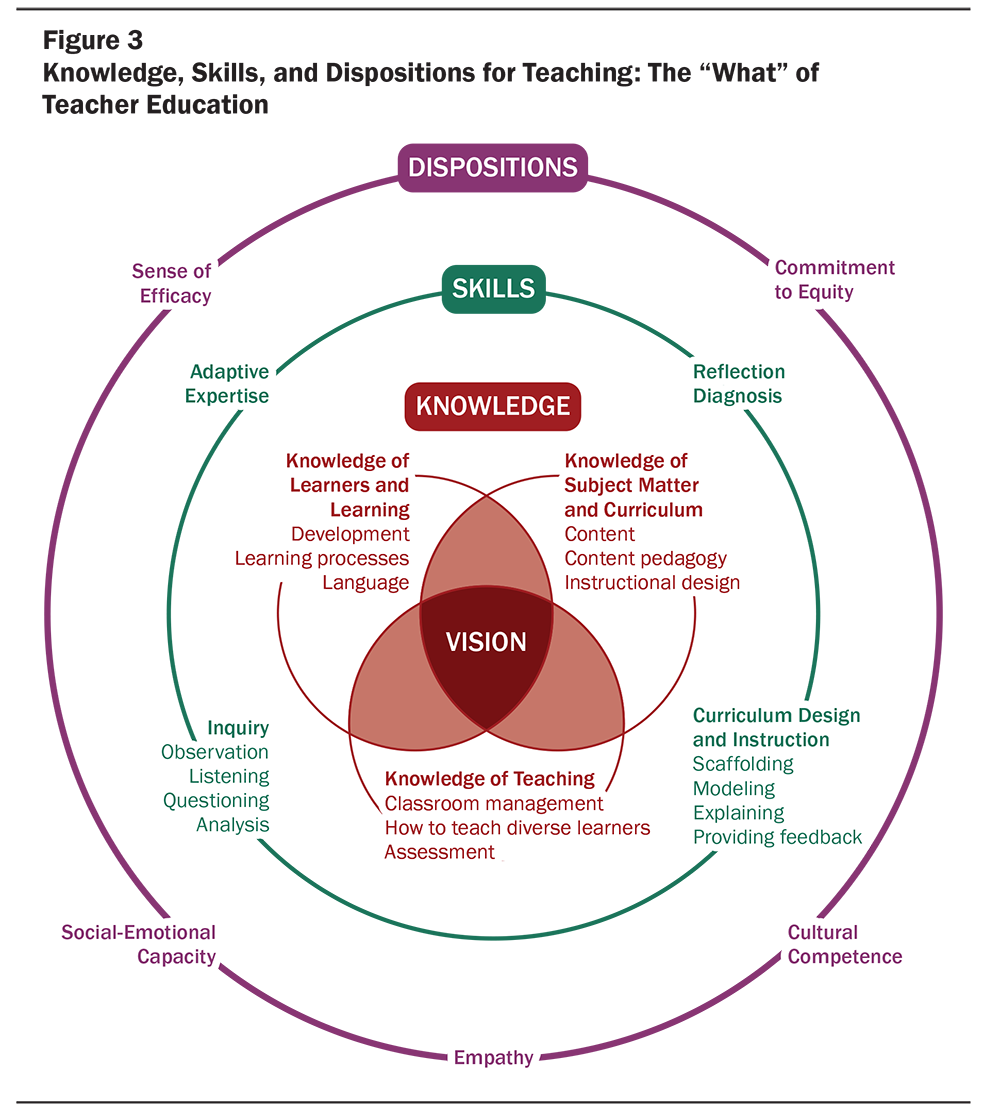

The National Academy of Sciences frameworks from two volumes on How People Learn suggest that common practices of effective teaching draw on several areas of knowledge:

- how students learn and develop within social contexts, including how cultural, social, emotional, and physiological experiences influence learning;

- how subject matter and curriculum goals can be taught in light of the social purposes of education; and

- how teaching can be structured in light of the content and learners to be taught, as informed by assessment and supported by a productive classroom environment that fosters the sense of belonging, agency, and purpose that supports motivation.

These areas of knowledge must be joined with skills of curriculum design and instruction, inquiry, reflection, and diagnosis to produce the adaptive expertise that enables teachers to make the connections between children and content that are necessary for learning. And these skills must be further joined to dispositions and attitudes that support empathy, social-emotional capacity, cultural competence, and a commitment to equity in support of each child’s well-being. School leaders need additional knowledge and skills to create the environments in which children and educators can thrive. These include an understanding of the pedagogical practices that support deep learning for children and adults; knowledge and skills for instructional leadership; and collective leadership practices that support collaborative buy-in from teachers, families, and others.

How Educators Can Develop the Necessary Knowledge, Skills, and Dispositions

Just as the call to utilize the science of learning and development to shape schoolwide practice places significant new demands upon educators and schools, so too does the need for educators to learn how to implement such practices place significant new demands upon educator preparation and professional development.

Designing learning experiences for adults

In order to design learning opportunities that are effective and useful for educators, an understanding of adult learning theory is essential. Adults bring with them substantial prior knowledge and interpreted experience, and they may have fixed ideas or preconceptions that influence their receptivity to new information. Theoretical frameworks in adult learning emphasize that learning should be related to adult learners’ prior experiences and professional purposes, ensure real-world applications, and allow learners to understand and experience the perspectives of others, so they can transform their own preconceptions into more responsive practices.

Key Strategies and Practices for Educator Preparation

Challenges of learning to teach for deeper learning and equity

The design of effective preparation programs must contend with at least three well-known challenges of learning to teach:

- The problem of the “apprenticeship of observation”—learning to teach requires a reframing of educators’ own previous experience as students in order to think about and understand teaching in new ways.

- The problem of enactment—teachers need not only to learn, but to learn to do.

- The problem of complexity—learning to teach requires that new teachers act purposefully to achieve multiple goals within a complex and busy classroom full of students who each bring their own knowledge, ideas, and social and cultural experiences with them.

These problems, along with the necessity of attending to the needs of adult learners, create parameters for prospective teachers’ learning that should guide the design of effective programs.

Key strategies for educator preparation program design

Program design should center around a coherent vision of whole child development, learning, and teaching that includes:

- pedagogical alignment around a coherent vision of whole child development, learning, and teaching that enables new teachers and school leaders to experience the very kinds of teaching strategies they are expected to develop for the pupils they work with;

- well-designed clinical experiences tightly linked to coursework that, together, integrate theory and practice to instantiate the developmental principles educators need to learn; and

- a developmental approach to the development of educators (just as educators use with their students) that occurs experientially in contexts that consciously support educators to go through the stages that eventually allow them to become increasingly expert.

Key practices for educator preparation

These overarching strategies support a set of educator preparation practices that research has shown make a strong difference in the capacities of educators. These key practices for educator preparation include:

- anchoring candidate learning in the study of human development and learning—in all its diversity—as the foundation and guide for the use of all other knowledge about teaching;

- integrating theory and practice through clinical experiences and coursework that allow teachers to learn and practice ever more sophisticated applications of knowledge and skill to reach greater mastery;

- providing opportunities for authentic practice, assessment, feedback, and reflection to accelerate learning;

- engaging in inquiry and analysis strategies that guide reflection and application, preparing candidates to ask productive questions when they encounter novel teaching challenges in different schools and community contexts and to employ such strategies with their own students; and

- collaborating in professional learning communities that provide mutual support, opportunities to learn from others’ perspectives and expertise, and modeling for leading a collaborative classroom.

Creating Systems That Support Educator Learning

Since children are not standardized and problems of practice are never routine, educators also need opportunities to continue to learn once they leave initial preparation. Effective professional development models that support educators’ practice share several features. These approaches:

- are content focused,

- incorporate active learning,

- support collaboration and space for teachers to learn together,

- use modeling of effective practice,

- provide coaching and expert support,

- offer opportunities for feedback and reflection, and

- are sustained over time.

Professional learning is most effective when it is part of a sustained approach at the school, district, and network levels that creates opportunities for learning, dialogue, and the development of shared practices at all levels of the system and among all of the members of the school community. An example of a successful schoolwide approach is the School Development Program, which teaches all members of the school community to use the principles of child and adolescent development to create a positive environment for children’s development along all of the developmental pathways—physical, social and emotional, linguistic, and cognitive.

Some schoolwide approaches, like the School Development Program, EL Education, and Institute for Student Achievement, have evolved into networks of schools that have been developed around practices grounded in the science of learning and development. These networks hold promise as a catalyst for developing educator capacity to address complex educational problems. Districtwide approaches that iterate on learning opportunities to deepen teachers and principals’ understanding, as well as district-level supervision and supports, are also important for sustained and successful transformations in pedagogy and school practice.

Conclusion

Concentrated efforts will be needed to create professional learning opportunities that can help educators develop the kinds of knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed to enable educators to use the insights from the science of learning and development to support their students through safe communities and secure relationships; integrated social, emotional, and academic supports; and the kinds of teaching that enable children ultimately to guide their own learning.

These efforts will be most successful if they offer pedagogical alignment that allows educators to experience the same kinds of learning they will use with students and if they engage educators in sustained, collegial efforts to practice new skills and strategies, while parallel learning and redesign occurs in districts’ central systems.

Educator Learning to Enact the Science of Learning and Development by Linda Darling-Hammond, Lisa Flook, Abby Schachner, and Steven Wojcikiewicz in collaboration with Pamela Cantor and David Osher is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, and the Carnegie Corporation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, and Sandler Foundation. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.