Adequate and Equitable Education in High-Poverty Schools: Barriers and Opportunities in North Carolina

Summary

This brief draws on a 2019 study of high-poverty schools in North Carolina conducted in support of the state’s efforts to comply with the North Carolina Supreme Court’s decision in Leandro v. the State of North Carolina. The study found that high-poverty schools provide inadequate and unequal educational resources and opportunities to their students, due in part to past policy choices, thus denying them a sound basic education. Further, high-poverty schools fail to address adverse out-of-school conditions that inhibit learning and development. Key recommendations outline policy steps to (1) expand high-quality early childhood education; (2) attract, prepare, and retain a diverse, high-quality workforce in high-poverty schools; (3) provide additional time, resources, and capacity in high-poverty schools; and (4) provide resources, opportunities, and supports to address out-of-school barriers to learning, using community schools or other evidence-based approaches.

The full 2019 report on which this brief is based is titled, Providing an Equal Opportunity for a Sound Basic Education in North Carolina’s High-Poverty Schools: Assessing Needs and Opportunities. The Action Plan and 12 associated reports can be found on the WestEd website.

The most difficult challenge policymakers and educators face in the United States today is disrupting the links among poverty status, race, and educational opportunities that systematically disadvantage young people of color from low-income families. Evidence examined in conjunction with North Carolina’s education adequacy and equity litigation, Leandro v. the State of North Carolina, can help unpack these links and suggest strategies for disrupting them.

In 1997, the North Carolina Supreme Court ruled that the state must provide equal opportunity for a sound basic education to all—one that allows students to attain proficiency in English language arts, math, history, geography, physical sciences, and civics and to succeed in postsecondary education or the workforce. Subsequent Leandro rulings emphasized the system’s failure to provide equal access to students who are socioeconomically disadvantaged or are members of racial, ethnic, and linguistic minority groups. The court identified these students as “at risk.” It found that equal access for these students requires additional resources, more instructional time, more focused attention, and adequately targeted remediation services, among other supports, beginning when children are infants.

North Carolina’s high-poverty schools require special attention if the state is to understand and remedy its failure to provide equal access to all students. A large percentage of students identified as at risk by the court, including 40% of all North Carolina students of color, attend public schools where the vast majority of students (i.e., 75% or more) come from low-income families. (This paper defines high-poverty schools as those in which 75% or more students come from families eligible for subsidized school meals.U.S. Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics has established the definitions of high- and low-poverty schools used in this analysis.) Students at these schools endure cumulative disadvantage from inadequate and unequal resources and opportunities at school and from the failure of schools to address adverse out-of-school conditions that inhibit learning and development.

High-poverty schools composed mostly of students of color provide even less access than high-poverty schools in which most students are White, as we discuss in this report. North Carolina has a history of slavery and segregation, as well as unequal funding of schools in ways that correlate with race. Students of color today face the harms of poverty disproportionately, as well as barriers stemming from systemic racism that have deep historical roots. Notably, the limitations faced by high-poverty and racially isolated schools are not incidental or random. Many result from policies that fail to provide the resources, support, and opportunities students require, thus exacerbating inadequacy and inequity.

Fortunately, policies designed to mitigate the effects of poverty on learning and child well-being are not only possible, but within reach. This brief recommends a coordinated and appropriately funded suite of policies that can enable high-poverty schools to provide an adequate and equitable education.

To study North Carolina’s high-poverty schools, Learning Policy Institute (LPI) researchers drew on findings from previous studies; conducted secondary analyses of existing administrative data sets; surveyed a representative sample of principals; and conducted observations, focus groups, and interviews with educational leaders, teachers, and school staff during site visits. After describing the demographics and student achievement in North Carolina schools, this brief summarizes the following key findings:

- High-poverty schools provide inadequate and unequal educational resources and opportunities, especially high-poverty schools serving large percentages of students of color.

- Adverse out-of-school conditions inhibit learning and development, particularly in high-poverty schools composed mostly of students of color, and few districts and schools address those barriers.

- Learning in high-poverty schools is disrupted by systemic barriers such as policies governing the state finance system, the teacher pipeline, supports for children and families, school accountability, charter schools, and vouchers.

The brief recommends a suite of evidence-based policies, including the establishment of community schools, that could enable high-poverty schools to provide an adequate and equitable education.

North Carolina School Demographics: Poverty and Race

Concentrated poverty is widespread in North Carolina. More than a quarter (404,505) of the state’s approximately 1.5 million public school students attend high-poverty schools (843 of the state’s 2,421 public schools, or 35%). As noted above, high-poverty schools are those in which 75% or more students come from families eligible for subsidized school meals. In contrast, only half that many students (199,000) are enrolled in the state’s 239 low-poverty schools (15%), where 25% or fewer students are economically disadvantaged.

The most obvious reason there are so many high-poverty schools is that 43% of North Carolina’s children live in low-income families. A second reason is that these children are increasingly concentrated in low-income neighborhoods. Both child poverty rates and the number of neighborhoods characterized by concentrated poverty are rising. Concentrated poverty neighborhoods increased from 37 in 2000 to 109 in 2016, and the percentage of people in poverty living in concentrated poverty neighborhoods more than doubled in that time (4.1% to 10.2%).U.S. Census Bureau. (n.d.). American Community Survey, 2014; Kennedy, B., II. (2018, April). Growing backwards: A growth in concentrated poverty signals increasing levels of economic and racial segregation. BTC Brief; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2011). Understanding neighborhood effects on concentrated poverty. Evidence Matters, Winter.

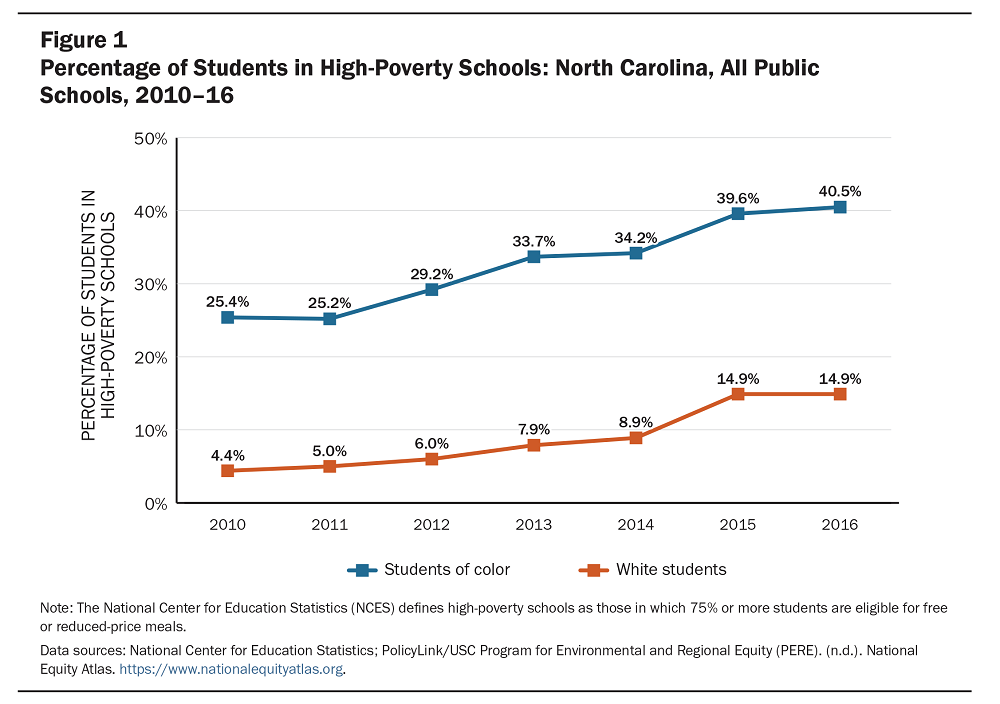

High- and low-poverty schools also reflect the intersection of race and economic status. Overall, students of color attend high-poverty schools at three times the rate of White students. The percentage of students of color attending high-poverty schools has also increased (Figure 1).

Three quarters of students at high-poverty schools are students of color, in contrast to 52% of the North Carolina student population overall.Twenty-five percent of North Carolina students are African American, 18% are Hispanic, 4% are Asian/Pacific Islander, 1% are Native, and 4% are from two or more of these groups. North Carolina’s low-poverty schools are mostly White. White students comprise 67% of those attending low-poverty district schools and 71% of those attending low-poverty charters.

High-Poverty Schools and Achievement

Students at high-poverty schools are less likely to receive a sound basic education. Leandro sets a clear bar for a sound basic education; students must display specific competencies and demonstrate proficiency on state tests. Across North Carolina, economically disadvantaged students are less likely to meet this bar than their more advantaged peers. These lower outcomes reflect, in part, the well-documented relationship between individual students’ socioeconomic status and school success.Ladd, H. F. (2012). Education and poverty: Confronting the evidence. Journal of Policy and Management, 31(2), 203–227; Mickelson, R. A. (2018). Is there systematic meaningful evidence of school poverty thresholds? National Coalition on School Diversity.

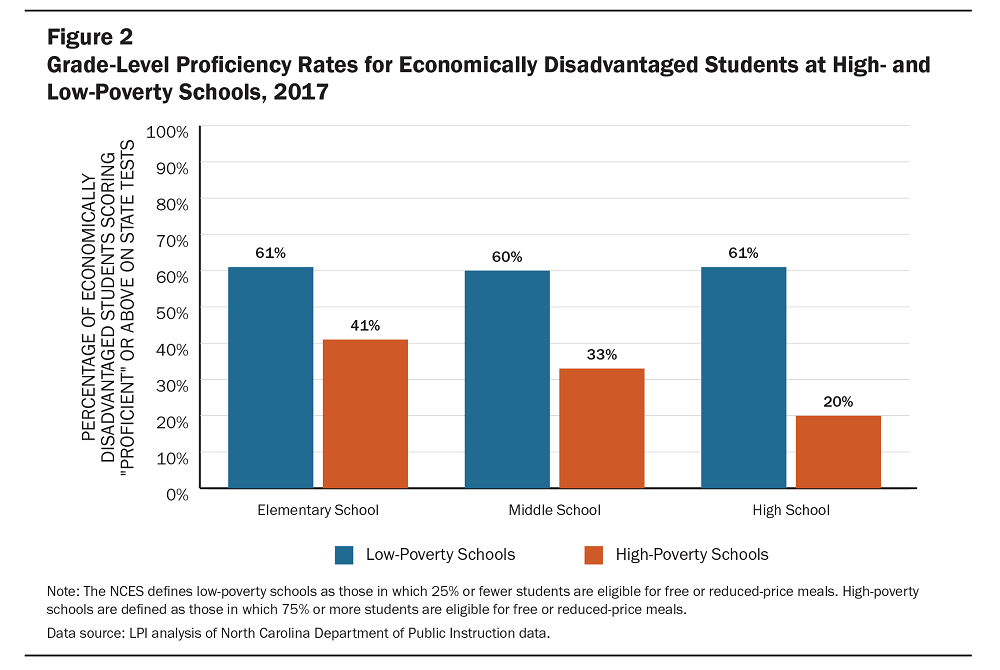

Consistent with considerable research, LPI’s analyses show a strong negative relationship between attending a high-poverty school and students from low-income families’ attainment of a sound basic education.Brazil, N. (2016). The effects of social context on youth outcomes: Studying neighborhoods and schools simultaneously. Teachers College Record, 118(7), 1–30; Mickelson, R. A. (2018). Is there systematic meaningful evidence of school poverty thresholds? National Coalition on School Diversity; Rumberger, R. W., & Palardy, G. J. (2005). Does segregation still matter? The impact of student composition on academic achievement in high school. Teachers College Record, 107(9), 1999–2045; Van Ewijk, R., & Sleegers, P. (2010). The effect of peer socioeconomic status on student achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 5(2), 134–150. Students from low-income families do far better at low-poverty schools than at high-poverty schools.Even without adjusting for relative levels of economic disadvantage, these data suggest that economically disadvantaged students generally benefit from attending low-poverty schools. In elementary schools, 61% of economically disadvantaged students in low-poverty schools demonstrate grade-level proficiency, compared to 41% at high-poverty schools. The gap increases to 27 percentage points in middle school and 41 percentage points in high school. (See Figure 2.)

Resources in High-Poverty Schools

Opportunity for a sound basic education is compromised at high-poverty schools, especially those serving many students of color, because they provide less access to school resources that have a positive impact. As a district administrator in a high-poverty school noted:

The larger middle school hasn’t had a steady 7th-grade math teacher for 5 years; this year they’ve had three 7th-grade math teachers. And now the 8th-grade math teacher is leaving.

Leandro laid out three tenets of a sound basic education: (1) “a competent, certified, well-trained teacher who is teaching the standard course of study by implementing effective educational methods” in every classroom; (2) “a well-trained competent principal with the leadership skills and the ability to hire and retain competent, certified and well-trained teachers who can implement an effective and cost-effective instructional program” in every school; and (3) adequate resources to meet all students’ educational needs and provide a sound basic education.Hoke County Board of Education v. State, 358 N.C. 605, 632, 637. (2004). (“Leandro II”).

As we elaborate below, prior research and LPI’s new analyses yielded the following findings:

- High-poverty schools provide less access to resources than low-poverty schools.

- High-poverty schools attended by 75% or more students of color provide less access than predominantly White high-poverty schools.

These findings help explain why high-poverty schools have worse outcomes than low-poverty schools.

Access to Educators in High-Poverty Schools

Prior research has established that access to an adequate supply of well-qualified and experienced teachers and low levels of teacher turnover are associated with higher student performance.Kini, T., & Podolsky, A. (2016). Does teaching experience increase teacher effectiveness? A review of the research. Learning Policy Institute; Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4–36. North Carolina schools with more experienced teachers, lower teacher turnover rates, more experienced and positive leadership of the principal, more resources for teaching and learning, and opportunities for professional development tend to have higher student performance, even after controlling for the proportion of economically disadvantaged students in the school and other characteristics.

Carolina’s high-poverty schools have fewer licensed teachers, fewer with advanced degrees, and fewer with National Board Certification. They also have more lateral entry teachers (i.e., those without full certification) and nearly twice as many beginning teachers (0–3 years’ experience), who make up almost 30% of the teachers at high-poverty schools.See also: Darling-Hammond, L., Bastian, K., Berry, B., Carver-Thomas, D., Kini, T., Levin, S., & McDiarmid, W. (2019). Educator supply, demand, and quality in North Carolina: Current status and recommendations. Learning Policy Institute.

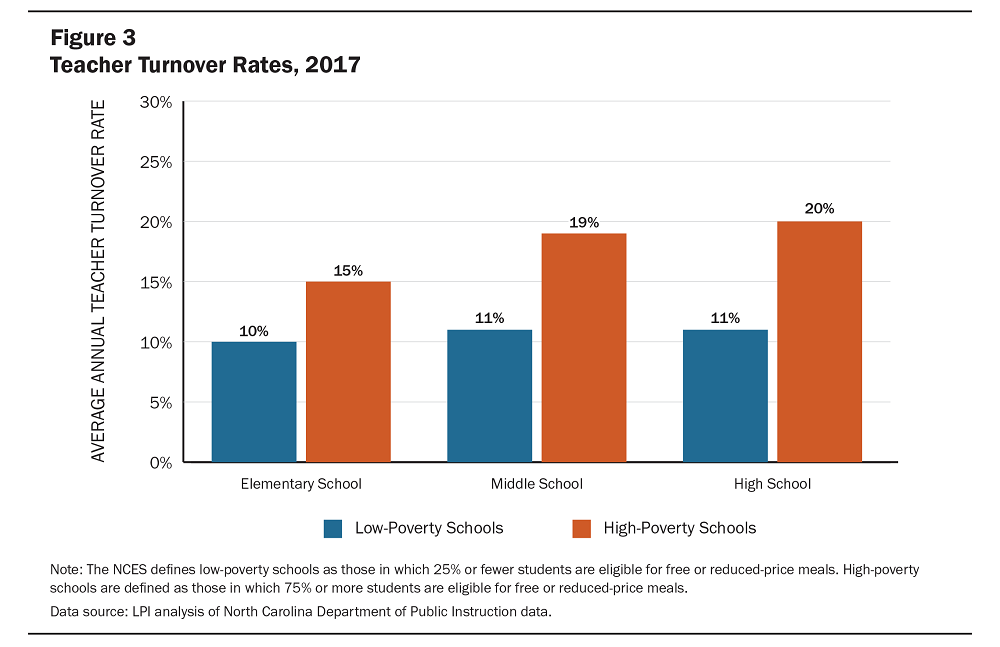

Teacher turnover rates are also typically much higher in high-poverty schools than in low-poverty schools. Rates are fairly consistent at low-poverty elementary, middle, and high schools and are much lower than at high-poverty schools. At the middle and high school levels, turnover at high-poverty schools is nearly double that at low-poverty schools. (See Figure 3.)

High-poverty schools also have significantly fewer experienced leaders who stay. In a statewide survey, 64% of North Carolina principals at high-poverty schools reported being in their jobs for 3 years or less, compared to 42% at low-poverty schools. Half of principals at low-poverty schools had led their schools for 4 to 10 years. Moreover, 82% of principals at low-poverty schools expect to stay in their positions for another 3 years; only 53% of principals at high-poverty schools reported such plans. Other responses show that principals at high-poverty schools feel less prepared to perform their jobs and are less satisfied with the support they receive from their districts, which are also plagued by leadership turnover.

Arguably, principal leadership matters more in high-poverty schools, since it is difficult to develop the necessary teacher capacity if new recruits are underprepared and depart soon after they arrive.Kraft, M. A., Marinell, W. H., & Yee, D. (2016). School organizational contexts, teacher turnover, and student achievement: Evidence from panel data. American Educational Research Journal, 53(5), 1411–1449. High teacher turnover undermines collective teacher efficacy—a strong predictor of student achievement.Hattie, J. (2015). The applicability of Visible Learning to higher education. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology, 1(1), 79–91. Low-poverty schools can overcome the ill effects of a less experienced principal who cannot support them because they are staffed by better prepared and more experienced teachers who are more likely to develop a strong sense of collective efficacy, even in the absence of strong and stable leadership.

Conditions for Teaching and Learning in High-Poverty Schools

The resources and learning opportunities at a school are associated with student outcomes.Jackson, K., Johnson, R., & Persico, C. (2016). The effects of school spending on education and economic outcomes: Evidence from school finance reforms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 13(1), 157–218; LaFortune, J., Rothstein, J., & Whitmore Schanzenbach, D. (2016). School finance reform and the distribution of student achievement [NBER Working Paper 22011]. National Bureau of Economic Research; Jackson, C. K. (2020). “Does School Spending Matter? The New Literature on an Old Question” in Tach, L., Dunifon, R., & Miller, D. L. (Eds.). Confronting Inequality: How Policies and Practices Shape Children’s Opportunities (pp. 165–186). American Psychological Association. A safe and supportive school climate is among the resources and conditions that have a positive impact.Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Learning Policy Institute. High-poverty schools provide less access to high-quality resources and conditions for teaching and learning. Leandro also specifies that an equal opportunity for a sound basic education requires that educators and schools have adequate resources to meet all students’ educational needs—suitable facilities and sufficient materials, challenging curriculum and instructional practices, school conditions that prioritize teaching and learning, positive school climate, positive relationships with families and community, and sufficient funding to support all of these. In each of these domains, we found discrepancies between low- and high-poverty schools. One high-poverty school, for example, had so few working computers, students had to take turns taking the state exam, which required weeks.

One strong predictor of students’ success is participation in rich and challenging curriculum and instruction.Mazzeo, C. (2010). College prep for all? What we’ve learned from Chicago’s effort. Consortium on Chicago School Research. One key indicator of such opportunity is the proportion of students to whom schools provide enriched learning opportunities designed for academically and intellectually “gifted” students. Across the state, about 12% of students statewide have access. However, these students are concentrated in low-poverty schools. Only 5% of students in high-poverty schools participate in these programs, compared to 23% in low-poverty schools. Similarly, at the high school level, there are dramatic differences in students’ access to advanced curriculum offerings. At low-poverty schools, 35% of students enroll in at least one Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate course. This is more than four times the rate of students at high-poverty schools (8%).

Finally, school climate greatly influences student outcomes, in part because exclusionary discipline practices diminish instructional time and opportunities for engagement. As one high-poverty district administrator lamented:

If the kids do something that violates discipline, they [teachers] make them put on a white T-shirt and sit in the “bad” chair in the back of the room. They are the outcast; they have to go before the “pride” [the in-group peers] to ask for forgiveness to be accepted back into the regular group. This really does something to a kid; it tears them down.

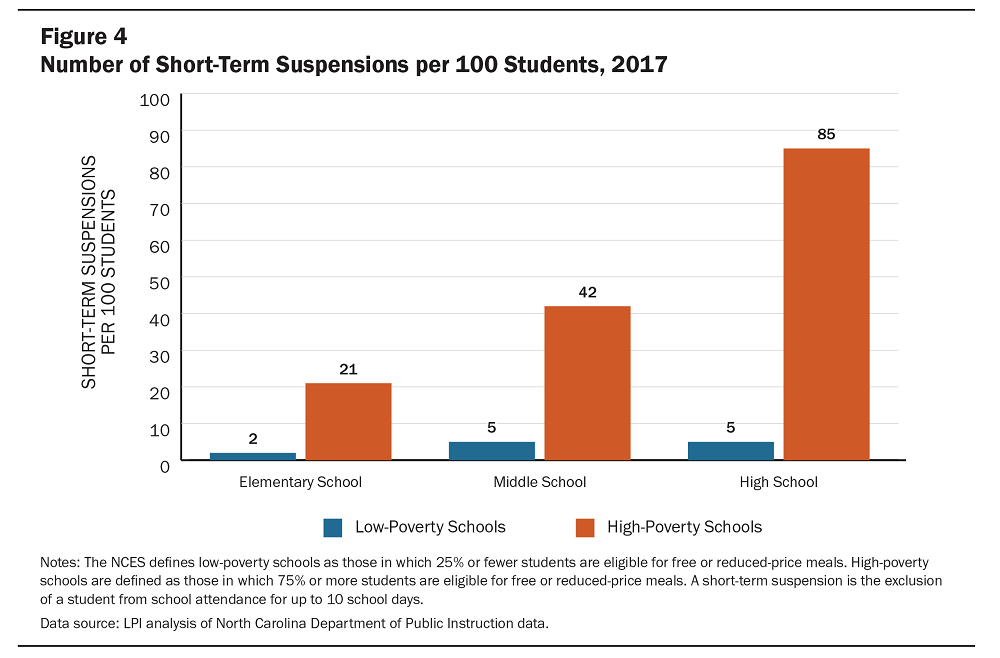

The extent to which schools use suspensions in response to student infractions of school norms is considerably higher in North Carolina’s high-poverty schools than in its low-poverty schools, with the starkest differences in high schools. (See Figure 4.)

These and many other disparities help explain why high-poverty schools have worse outcomes than low-poverty schools. The lack of critical school resources is particularly damaging in high-poverty communities because they cannot be offset, as they often are in advantaged ones, by families paying for out-of-school-time learning support and enrichment—tutors, art and music lessons, summer programs, and more.

Race and Resources in High-Poverty Schools

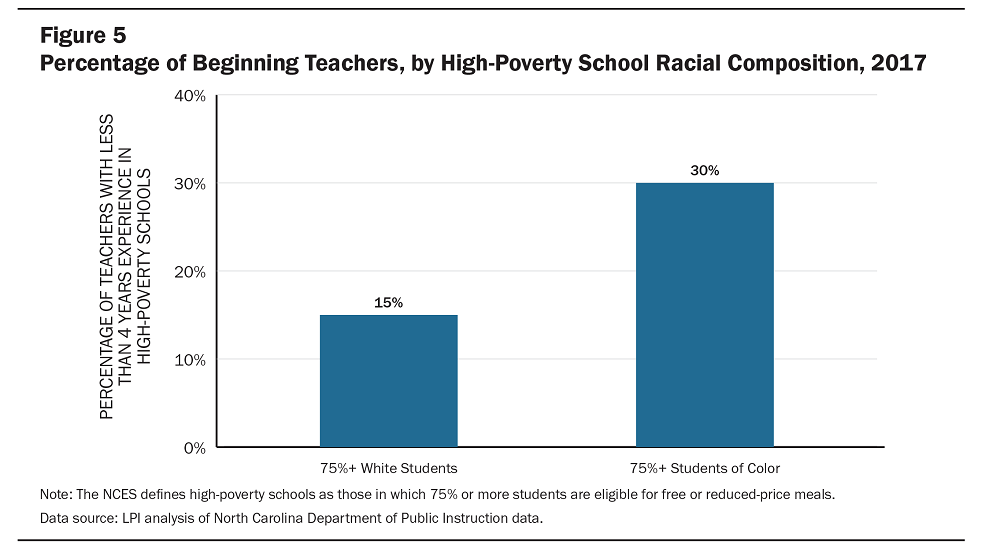

Students of color are far less likely than White students to attend low-poverty schools that provide greater access to high-quality educators and resources. Additionally, predominantly White high-poverty schools provide greater access to resources outlined by the Leandro tenets than do high-poverty schools composed primarily of students of color. In fact, high-poverty schools that are composed predominantly of students of color have beginning teachers at twice the rate of high-poverty schools in which most students are White. (See Figure 5.)

Opportunities to participate in enriched curriculum and learning experiences in high-poverty schools also differ along racial lines. A recent study found that in North Carolina’s high-poverty schools, Asian and White students were consistently overrepresented and Black and Latino/a students were underrepresented in enriched courses and programs designed for academically and intellectually gifted students.Yaluma, C., & Tyner, A. (2018). Is there a gifted gap? Gifted education in high-poverty schools. Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

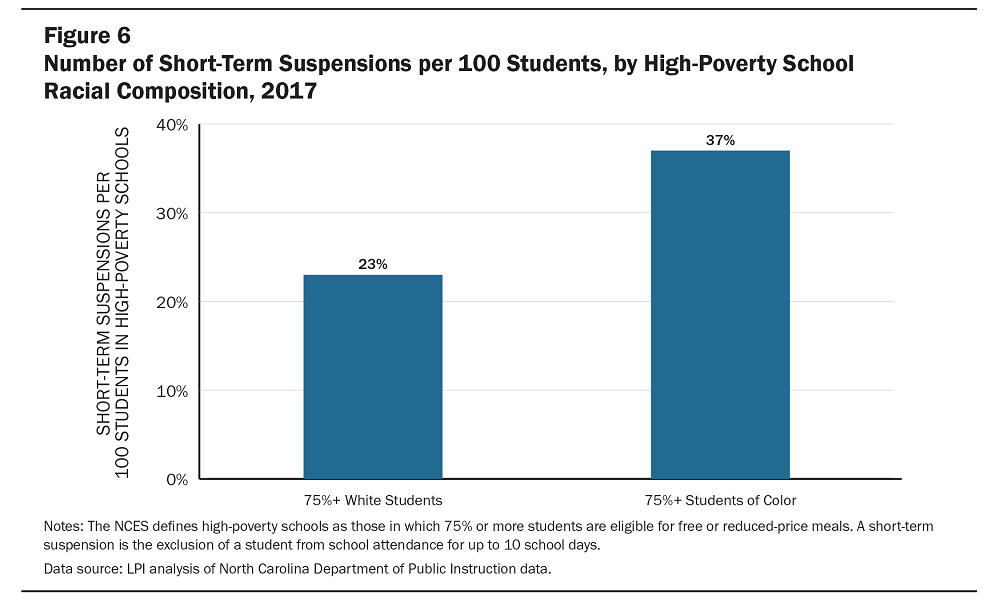

Additionally, high-poverty schools appear to approach school climate issues differently depending on their racial composition. Consistent with the differences noted earlier, high-poverty schools with large percentages of students of color have suspension rates that are more than 50% higher than those of schools with large percentages of White students. (See Figure 6.)

Out-of-School Conditions

Opportunity for a sound basic education in high-poverty schools is compromised further, especially for students of color, by unaddressed barriers to learning that stem from adverse out-of-school conditions associated with concentrated poverty. A principal in a rural high-poverty elementary school explained:

One day you get out there and actually see where the children you serve on a daily basis come from. Several teachers came back after delivering food and broke down in tears telling me what they saw. A student was living in a home with no roof; they’ve got a tarp for a roof kept on by bricks and tires. Homes didn’t have doors.

Communities of concentrated poverty expose children to adverse out-of-school conditions that pose barriers to learning: lack of high-quality care for young children, food insecurity, substandard housing or homelessness, unsafe neighborhoods, lack of access to social and health services, and a range of traumatic experiences.Ladd, H. F. (2012). Education and poverty: Confronting the evidence. Journal of Policy and Management, 31(2), 203–227. Accordingly, living and going to school in communities of concentrated poverty compounds the disadvantages of attending schools with fewer high-quality learning resources and opportunities, as described above. The Leandro court recognized this and ruled that at-risk students need more and different resources and interventions to help counter the harms of cumulative social and academic disadvantages associated with poverty.

In neighborhoods with high-poverty schools, 64% of children live in families with incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level—qualifying for public assistance such as Medicaid and food stamps. In contrast, 19% of children in communities with low-poverty schools live in families at this poverty level. The negative effects of concentrated poverty are found once poverty rates exceed 20%, and they grow rapidly before leveling off around 40%.Galster, G. C. (2010, February 4–5). The mechanism(s) of neighborhood effects: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. Paper presented at the ESRC Seminar. Many studies and reports document these adverse conditions in North Carolina’s high-poverty communities.Using 2015 data, the UNC Center for Urban and Regional Studies documented North Carolina’s severely distressed communities as census tracts, usually representing an area comprising approximately 4,000 people, that meet three criteria: an unemployment rate equal to 14.5% or less, a yearly income that is less than or equal to $16,921, and a poverty rate greater than or equal to 24%.

Race and Out-of-School Conditions in High-Poverty Schools

These negative effects are experienced disproportionately by students of color. Black North Carolinians are far more likely than White North Carolinians to live in neighborhoods with the highest poverty rates (40% or higher).Kneebone, E., & Holmes, N. (2016). Concentrated poverty in the wake of the Great Recession. Brookings Institution. Nearly half of high-poverty schools are in majority-minority communities (defined as the census tract in which the school is located). In contrast, 99% of low-poverty schools are in majority-White communities.

These findings show that Black, Latino/a, and Native children in North Carolina are more likely than White children to experience a double burden. They suffer the negative learning consequences of living in communities of concentrated poverty; at the same time, they attend schools with fewer resources and opportunities to learn.

Key to offsetting the harms of concentrated poverty are providing high-quality prekindergarten programs, using whole child approaches to k–12 schooling, connecting wraparound child well-being services to schools, providing school support personnel at levels that meet national standards, and offering additional learning time and opportunities beyond the regular school day. Although some North Carolina high-poverty schools and communities provide such supports and interventions, most do not. Below are examples of insufficient access to early childhood programs and to wraparound services in high-poverty k–12 schools.

Early Childhood Education

Rigorous research has demonstrated that the state-funded North Carolina pre-k program (NC Pre-K) for students from low-income families has produced both short- and long-term benefits through grade 8.Dodge, K., Bai, Y., Ladd, H. F., & Muschkin, C. G. (2019). Evaluation of North Carolina early childhood programs and policies among middle school students. Unpublished manuscript, Duke University. However, too few of the state’s children have access to those programs, particularly children defined by Leandro as at risk. Indicators published by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services show that in 2019 less than half of the eligible children were being served by NC Pre-K—only 24% of all North Carolina 4-year-olds. Recent estimates are that the unmet need is 33,000 eligible young children.National Institute for Early Education Research. (2019). Barriers to expansion of NC Pre-K: Problems and potential solutions. Counties with the lowest rates of serving those eligible for NC Pre-K are also those with the highest child poverty. On average, 23% of children in these 40 low-serving counties are poor.U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. (n.d.). Percent of total population in poverty, 2019.

A second indicator of limited access is that only 11% of economically disadvantaged infants and toddlers and only 17% of economically disadvantaged 3- to 5-year-olds are in high-quality private centers.North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). NC Early Childhood Action Plan data dashboards (accessed 04/05/19). A third indicator is that Head Start programs fall far short of serving eligible children, and the percentage of eligible 3- to 5-year-old children enrolled has declined over the past decade.North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). NC Early Childhood Action Plan data dashboards (accessed 04/05/19). Compounding all of these problems is that North Carolina lacks enough well-qualified teachers to staff its existing programs adequately.

Wraparound Services and Whole Child Approaches

Another way to address the harms associated with poverty is to provide wraparound services and whole child approaches to education. This includes family engagement, community involvement, health services, counseling, and psychological and social services. North Carolina has a few programs to provide additional supports and services to students impacted by concentrated poverty. However, these programs are largely disjointed, uncoordinated, and not concentrated in the areas of greatest need. Moreover, many of the supports and interventions that do exist are not integrated into the public education system. One concrete example of program inadequacy is the state’s summer nutrition programs that provide food for children who depend on the subsidized meals during the school year. The percentage of eligible children served by the program is quite small—with only one county serving more than 40% and over half of the counties serving 10% or less.Mackinson, I. (2018, August 3). Local, national barriers leave millions of child feeding dollars on the table. North Carolina Health News.

The Department of Public Instruction’s Whole Child, Whole School, Whole Community program is the only state-run program in North Carolina aimed at making schools hubs of support for students and families experiencing adverse out-of-school conditions. Although this model holds considerable promise, it is being implemented currently in only 11 counties.

Some communities have mounted local efforts to provide whole child supports. One is Asheville and Buncombe County’s Middle Grades Network—a partnership between Asheville City Schools; Buncombe County Schools; United Way of Asheville and Buncombe County; the University of North Carolina at Asheville; and representatives of more than 50 health, social service, higher education, and youth services community partners. Together, they work toward safe and welcoming schools; supports for families; and graduating all students ready for college, career, and community. A second example is Communities In Schools of North Carolina, which is part of the national Communities In Schools network. Each community school has a student support specialist who works with school administrators to assess needs, develop a plan, and build a team to provide supports and interventions to schools and students.

Neither program has state support. They are voluntary, funded by charity, and dependent upon local partnerships rather than being part of a public infrastructure with the resources needed for sustainability.

Systemic Factors

Many barriers to learning in high-poverty schools do not originate and cannot be solved at the school level. Policies related to the state finance system, the teacher pipeline, supports for children and families, school accountability, charter schools, and vouchers create or perpetuate many of these barriers.

Perhaps most significant, the structure of North Carolina’s school finance system, together with the steady, decade-long decreases in funding levels, has compromised high-poverty schools’ ability to provide a sound basic education, particularly in high-poverty counties. As noted in the Leandro Finance Report (a companion to this study):

The statewide distribution of funding was found to be inequitable in two key ways: (1) school districts lack the funding necessary to meet the educational needs of historically underserved student populations, and (2) funding across districts is inequitable due to differences in local funding, differences in state funding received through the Classroom Teacher allotment, and differences in regional costs.Willis, J., Krausen, K., Berg-Jacobson, A., Taylor, L., Caparas, R., Lewis, R., & Jaquet, K. (2019). A study of cost adequacy, distribution, and alignment of funding for North Carolina’s k–12 public education system. WestEd.

The negative impact of these structural constraints and funding declines has been exacerbated by the inability of low-wealth districts to raise additional funds through local taxation, something wealthier counties routinely do.

Second, educator pipeline policies—preparation, recruitment, retention, etc.—limit high-poverty schools’ ability to attract and keep high-qualified teachers and principals. Teacher salary cuts and eliminating pay increases based on education level have reduced the supply of teachers; fewer certified and experienced teachers are attracted to teach in low-performing schools, especially in rural areas.Darling-Hammond, L., Bastian, K. C., Berry, B., Carver-Thomas, D., Kini, T., Levin, S., & McDiarmid, W. (2021). Educator supply, demand, and quality in North Carolina: Current status and recommendations. Learning Policy Institute.

Third, the state’s punitive accountability system has undermined high-poverty schools. The state’s strategy of sanctioning low-performing schools—most of which serve low-income students and students of color in communities with few resources—has made it harder to attract and retain qualified teachers.Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., Vigdor, J. L., & Diaz, R. A. (2004). Do school accountability systems make it more difficult for low-performing schools to attract and retain high-quality teachers? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 23(2), 251–271. The associated hiring of untrained teachers, through the state’s lateral entry route, had strong negative effects on student achievement.Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2007). How and why do teacher credentials matter for student achievement? [NBER Working Paper 12828]. National Bureau of Economic Research; Henry, G., Thompson, C. L., Bastian, K. C., Fortner, C. K., Kershaw, D. C., Purtell, K. M., & Zulli, R. A. (2010). Impacts of teacher preparation on student tests scores in North Carolina: Teacher portals. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Carolina Institute for Public Policy.

Fourth, although the state has endorsed the whole child, whole school, whole community approach to providing additional supports and services, the program has been implemented in very few locations. A lack of state resources and staff capacity to oversee this program suggests a lack of state commitment to interventions that help mitigate the barriers to learning in high-poverty communities.

Fifth, state policies limit access to high-quality prekindergarten programs. State funding covers approximately 60% of the cost of each student, leaving counties to cover the remaining 40% through other funding sources. The lack of adequate certification policies has produced a prekindergarten workforce without sufficient training and credentials. Better compensation and benefits and more effective certification policies are needed to support a stable, highly qualified workforce. The median base pay for early childhood teachers is $22,800, usually without benefits. As a result, 40% of these teachers are on public assistance, especially the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Educator turnover in the prekindergarten sector is high.

Finally, charter schools and opportunity scholarship policies increase the disadvantage in high-poverty schools. Charter students (who often are more advantaged compared to non-charter students) take with them the average cost per student in the district in which the schools are located, but their departure does not diminish fixed infrastructure costs, such as buildings and transportation. Because charter schools are funded at the average cost per student in the district in which the schools are located, charters receive higher per-pupil funding in districts with many teachers at the high end of the scale. These tend to be low-poverty schools. These policy-related barriers are experienced most profoundly by economically disadvantaged students of color attending high-poverty schools, where they face barriers to learning that have deep historical roots in state and local policy—including the prohibition of literacy for slaves, Jim Crow schools, and resistance to integration.

Recommendations

There is a pressing need to lower the barriers that students in high-poverty schools face and address the intersection of race and poverty in schooling inequalities. Below, we offer evidence-based recommendations that can put high-poverty schools on a path of continuous improvement. Because students of color at high-poverty schools have the least access to a sound basic education, the state should use the racial composition of schools as an indicator of where intensive actions are needed most and to make sure that all interventions are culturally and historically responsive.The DARE tool is one resource for a race-conscious approach to enacting an equity-oriented vision of educational justice. Hyler, M. E., Carver-Thomas, D., Wechsler, M., & Willis, L. (2020). Districts advancing racial equity (DARE) tool. Learning Policy Institute.

1. Expand a high-quality early childhood system so that publicly funded, high-quality pre-k and early childhood education programs are accessible for all 3- to 5-year-olds in high-poverty communities.

North Carolina’s early education system leads the nation in the quality of its infrastructure and standards. However, tens of thousands of children who could benefit are not being served. The following could help meet the unmet need:

- Consider redefining public education to include pre-k, funding it with the same mechanisms as k–12, and sharing public school infrastructure, including transportation.

- Increase funding by adding a “concentration of poverty” factor to offset the additional costs of high-quality early childhood education in high-poverty communities.

- Offer financial incentives for high-quality providers (that do not currently participate) to serve children from low-income families through the NC Pre-K program.

- Support providers to braid funds from two or more funding streams, such as Early Head Start, Head Start, the child care subsidy programs, NC Pre-K, and infant and toddler programs, to deliver high-quality full-day and full-year programming to vulnerable young children and families.

- Develop and use an early childhood data system to target need and monitor access within and between counties.

2. Attract, prepare, and retain a highly qualified, diverse k–12 educator workforce in high-poverty schools.

North Carolina must balance demand and supply of educators in high-poverty schools. The following could help achieve that balance:

- Set a 5-year goal of reducing less-than-fully qualified educators in high-poverty schools to less than 5% and those with fewer than 3 years of experience to less than 10%.

- Target recommendations for improving the supply and quality of teachers and leaders at high-poverty schools, including, but not limited to, incentives for serving in those schools.

- Target recruitment and Grow-Your-Own preparation toward candidates of color in order to diversify the workforce at high-poverty schools.

- Include in teacher preparation and ongoing professional learning a specific focus on effective teaching in high-poverty communities and communities of color, including a focus on culturally and linguistically responsive teaching, a whole child approach, trauma-informed practices, positive/restorative discipline methods, and coordinating supports that mitigate the barriers posed by adverse out-of-school conditions.

- Adopt competitive compensation and retention strategies—such as state-provided salary supplements to teachers in high-poverty schools—in low-wealth counties.

- Provide special support, guidance, and technical assistance to improve professional working conditions in high-poverty schools.

3. Provide additional time, resources, and capacity in high-poverty schools to support instruction that provides all students an equal opportunity for a sound basic education.

North Carolina could make the following investments to reduce systemic barriers and increase the quality of instruction in high-poverty schools:

- Add “concentration of poverty” weights to the state’s funding mechanisms (allocations, including teacher positions, and other categorical programs) to offset the additional costs associated with retaining high-quality educators in high-poverty schools.

- Ensure adequate infrastructure to support teaching and learning—that is, facilities in good repair, adequate technology (hardware, software, bandwidth), and transportation.

- Reduce class size (or the comparable teacher–student ratio) in ways consistent with research that has demonstrated impact on student success.

- Expand instructional time in elementary and middle schools by lengthening the school days and year, using additional time for personalized academic supports; enrichment activities linked to the curriculum; and access to culturally responsive arts and music programs, athletics, and electives supported by community partnerships.

- Support positive behavioral interventions and supports and restorative practices to establish a positive discipline climate and increase student engagement.

- Expand access to college readiness in high-poverty high schools—including advanced coursework and materials that are culturally and linguistically responsive (e.g., ethnic studies courses), dual enrollment, and other college-credit-earning opportunities.

- Expand access to college pathways programs by providing transportation, funding textbooks and other costs, and synchronizing school and community college schedules.

- Provide equitable access to career readiness in high-poverty high schools, including pathways that integrate career and technical education with rigorous academic courses.

- Revise charter school policies to eliminate fiscal pressures on high-poverty schools and prevent increased racial and economic segregation.

- Include indicators of growth on multiple measures, including access to the Leandro tenets, in the state accountability system. Use those data to inform interventions and resources that increase stability and morale in high-poverty schools.

4. Provide resources, opportunities, and supports to address out-of-school barriers to learning, using community schools or other evidence-based approaches.

North Carolina can build on the considerable local interest in whole child approaches and integrating social supports into high-poverty schools with policies providing funding, technical assistance, and a support infrastructure for high-quality community schools. Examples include the following:

- Provide state-level or regional support for high-poverty schools to transition to a community schools approach, building on the state’s underused Whole Child, Whole School, Whole Community model.

- Provide districts support and flexibility to use strategies including: (1) wraparound services that meet health, social, and other child and family needs; (2) expanded learning time and opportunities, including after-school and summer programming; (3) family and community engagement; and (4) collaborative practices and leadership.

- Provide a full-time community schools coordinator at each high-poverty school (with appropriate training and support) to assess local needs and assets and to integrate social, academic, and health supports (including mental health) into the school.

- Extend school hours to accommodate family work schedules and provide expanded programs for students and families with nonprofit community partners.

- Add flexibility to permit blending and braiding of state funding streams in education and other public agencies to support innovative approaches to community schools.

- Align and locate at the school services from other public agencies (e.g., health and human services, food distribution services, housing services, public safety services, immigration services, workforce programs, and youth involvement programs) that address adverse out-of-school conditions.

- Establish an interagency advisory body to find ways for agencies to share data and coordinate initiatives that support families in high-poverty communities and schools.

Conclusion

The Leandro ruling leaves little doubt about what needs to be done. The conditions in and around high-poverty schools and communities result in far too many students not being educated adequately to participate in the global economy or become active, informed citizens. The four sets of recommendations outlined here will not solve all the challenges high-poverty students face, but they will solve many of them. The evidence of this is clear.

This research was supported by the Spencer Foundation. Core operating support for LPI is provided by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, and Sandler Foundation.

Adequate and Equitable Education in High-Poverty Schools: Barriers and Opportunities in North Carolina (research brief) by Jeannie Oakes, Peter W. Cookson, Jr., Janel George, Stephanie Levin, Desiree Carver-Thomas, Fred Frelow, and Barnett Berry is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.