Educator Supply, Demand, and Quality in North Carolina

Summary

This brief summarizes a 2019 study of educator supply, demand, and quality in North Carolina conducted by the Learning Policy Institute in collaboration with the Education Policy Initiative at Carolina and WestEd. That study supported the state’s ongoing efforts to meet the standard set in the North Carolina Supreme Court’s decision in Leandro v. the State of North Carolina.

The study found that access to qualified teachers and administrators was increasingly limited and inequitable in the state. To guarantee that access, it recommended expanding high-quality teacher pipelines and training, updating preparation and professional development, and rationalizing and improving compensation and evaluation.

The 2019 report is titled, Educator Supply, Demand, and Quality in North Carolina: Current Status and Recommendations. The Action Plan and 12 associated reports can be found on the WestEd website.

In a landmark decision in Leandro v. the State of North Carolina (Leandro), the Supreme Court of North Carolina found that children have a right to qualified teachers and principals who can prepare students for college and careers and meet the needs of those placed at risk. Providing such high-quality educators for each child demands an adequate supply of educators who are equitably distributed, along with supports for ongoing professional learning that enables educators to meet children’s needs.

This expectation was not met at the time of the Leandro decision in 2004 and has not been met in the years since. To develop recommendations for meeting the Leandro standard, the study on which this brief is based documented the supply of and demand for qualified educators, their distribution throughout the state, and the conditions of practice that are known to influence recruitment and retention.

Extensive research on the human capital system in North Carolina addresses the quality and effectiveness of teachers who enter the profession through different pathways, as well as the nature of working conditions across schools, the factors affecting attrition, and the effects of the state’s accountability system on teacher turnover.See, e.g., Burkhauser, S. (2017). How much do school principals matter when it comes to teacher working conditions? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(1), 126–145; Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2007). How and why do teacher credentials matter for student achievement? [NBER Working Paper w12828]. National Bureau of Economic Research; Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2011). Teacher mobility, school segregation, and pay-based policies to level the playing field. Education, Finance and Policy, 6(3), 399–438; Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., Vigdor, J. L., & Aliaga-Diaz, R. (2004). Do school accountability systems make it more difficult for low-performing schools to attract and retain high-quality teachers? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 23(2), 251–271; Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., Vigdor, J. L., & Wheeler, J. (2007). High-poverty schools and the distribution of teachers and principals. North Carolina Law Review, 85(5), 1345–1380; Heissel, J. A., & Ladd, H. F. (2016). School turnaround in North Carolina: A regression discontinuity analysis [CALDER Working Paper 156]. National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research; Henry, G. T., Purtell, K. M., Bastian, K. C., Fortner, C. K., Thompson, C. L., Campbell, S. L., & Patterson, K. M. (2014). The effects of teacher entry portals on student achievement. Journal of Teacher Education, 65, 7–23; Horoi, I., & Bhai, M. (2018). New evidence on National Board Certification as a signal of teacher quality. Economic Inquiry, 56(2), 1185–1201; Jackson, C. K., & Bruegmann, E. (2009). Teaching students and teaching each other: The importance of peer learning for teachers. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(4), 85–108; Ladd, H. F. (2011). Teachers’ perceptions of their working conditions: How predictive of planned and actual teacher movement? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(2), 235–261; Ost, B., & Schiman, J. C. (2015). Grade-specific experience, grade reassignments, and teacher turnover. Economics of Education Review, 46, 112–126. This literature echoes the findings of a broader body of national research that finds that teacher experience and qualifications influence student achievement—especially that of students of color and of those from low-income families—and that educator quality is both influenced by state policies and inequitably distributed.Goldhaber, D., Quince, V., & Theobald, R. (2018). Has it always been this way? Tracing the evolution of teacher quality gaps in U.S. public schools. American Educational Research Journal, 55(1), 171–201; Ladd, H., & Sorensen, L. (2015). Returns to teacher experience: Student achievement and motivation in middle school [CALDER Working Paper 112]. National Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research; Xu, Z., Özek, U., & Hansen, M. (2015). Teacher performance trajectories in high- and lower-poverty schools. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(4), 458–477.

Further, the factors that influence teacher supply, demand, and shortages are well documented: Supply is influenced by the recent decline in teacher education enrollments, and demand is influenced by attrition from the profession, which accounts for nearly 90% of annual hiring needs.Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. Learning Policy Institute. Similarly, the demand for school leaders is influenced by the sizeable turnover of principals, who leave both their schools and the profession.Levin, S., Scott, C., Yang, M., Leung, M., & Bradley, K. (2020). Supporting a strong, stable, principal workforce: What matters and what can be done? National Association of Secondary School Principals and Learning Policy Institute.

Investments in Teaching and Leadership

North Carolina was recognized during the 1980s and 1990s as an example of how state policymakers could turn a state around through strong investments in teachers’ knowledge and skills, in standards for students and teachers, and in early childhood support and education.

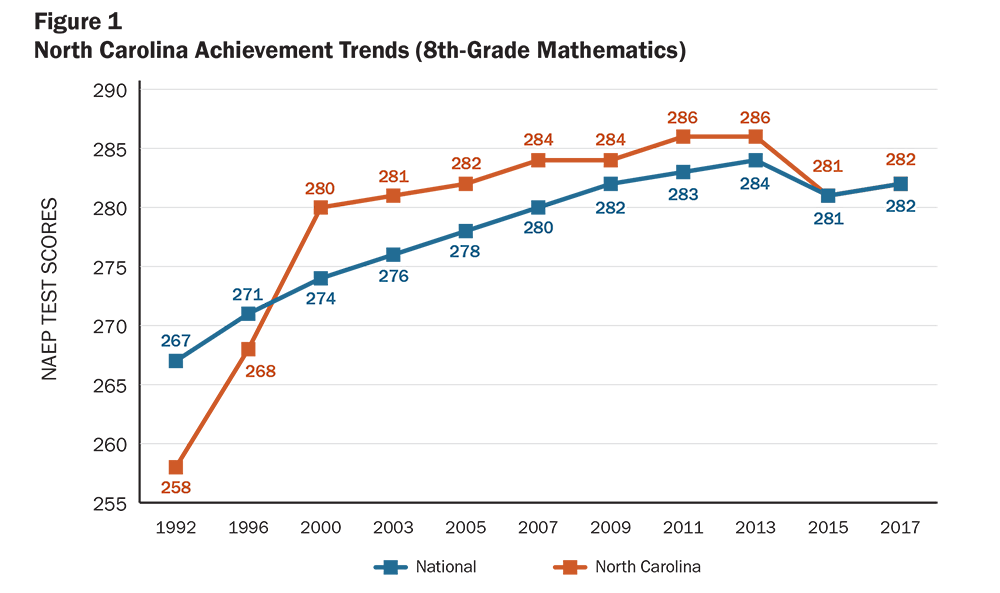

In the 1990s, for example, North Carolina posted the largest student achievement gains in mathematics of any state and realized substantial progress in reading. The state also narrowed the achievement gap between White students and Black, Latino/a, and Native American students.National Education Goals Panel. (1998). The National Education Goals report: Building a nation of learners, 1998. U.S. Government Printing Office. However, cutbacks that began during the recession after 2008 and grew much deeper beginning in 2011 have eliminated or greatly reduced many of the programs put in place during the 1980s and 1990s and have begun to undermine the previous quality and equity gains. (See Figure 1.)

North Carolina’s reforms were launched in 1983, during Governor James B. Hunt’s second term. North Carolina’s Elementary and Secondary School Reform Act enhanced school funding; raised teacher salaries to the national average; upgraded curriculum expectations for students; increased standards for entering teaching and school administration; increased standards for educator certification and for the approval of schools of education; created expectations of local schools for staffing, evaluation of personnel, class sizes, and instructional time; authorized a new scholarship program to recruit talented individuals into teaching; and encouraged expanded professional development. This bill laid the groundwork for a series of initiatives throughout the 1980s, which were expanded further in the 1990s. Highlights of these efforts include the following:

- The highly selective North Carolina Teaching Fellows program paid all college costs, including an enhanced and fully funded teacher education program, in return for several years of teaching.National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future. (1996). What matters most: Teaching for America’s future.

- One of the nation’s first beginning teacher mentoring programs offered support to new teachers and financial incentives for mentor teachers.National Education Goals Panel. (1998). The National Education Goals report: Building a nation of learners, 1998. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- Professional development academies and a North Carolina Center for the Advancement of Teaching offered additional help to novice and veteran teachers for learning to teach the state curriculum.

- Teacher salaries were raised to the national average.

- Supports and incentives were offered for teachers to pursue National Board Certification of accomplished practice, including a 12% increase to base salary for those who succeeded in becoming certified.

- The Principal Fellows Program provided competitive, merit-based scholarship loans and paid internships to attract and prepare talented educators seeking a master’s degree in school administration and a principal position in North Carolina public schools.Bastian, K. C., & Fuller, S. C. (2015). The North Carolina Principal Fellows Program: A comprehensive evaluation. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Education Policy Initiative at Carolina; University of North Carolina Academic and University Programs Division. (2015). Great teachers and school leaders matter.

Recent Challenges and the Current Status of Teaching in North Carolina

Most of the policies listed above were reduced or eliminated beginning in 2008 and continuing through the following decade due to the Great Recession as well as political changes in the state. Salaries declined relative to other professions and states, mentoring and professional development programs were reduced or eliminated, supports for entry and preparation were eliminated, and alternative paths into teaching that do not require prior preparation were introduced. In addition, the state accountability program imposed increasingly severe sanctions on low-performing schools—most of which serve economically disadvantaged students in communities of color that have fewer resources. Rather than strengthening these schools, this exacerbated their difficulties in attracting and retaining qualified teachers. Research found that the associated recruitment of untrained teachers into these hard-to-staff schools through the state’s alternative “lateral entry route” also had strong negative effects on student achievement.Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., Vigdor, J. L., & Aliaga-Diaz, R. (2004). Do school accountability systems make it more difficult for low-performing schools to attract and retain high-quality teachers? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 23(2), 251–271; Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2007). How and why do teacher credentials matter for student achievement? [NBER Working Paper w12828]. National Bureau of Economic Research; Henry, G. T., Purtell, K. M., Bastian, K. C., Fortner, C. K., Thompson, C. L., Campbell, S. L., & Patterson, K. M. (2014). The effects of teacher entry portals on student achievement. Journal of Teacher Education, 65, 7–23. In the decade after these policy shifts took place, achievement declined and inequality grew.Hui, T. K. (2018). North Carolina slips in national ranking on public education. The News and Observer; Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). Investing for student success: Lessons from state school finance reforms. Learning Policy Institute.

North Carolina has gone from having a very highly qualified teaching force to having one that is extremely uneven in terms of the numbers of candidates; the quality of their preparation, particularly for teaching in high-poverty schools; and the extent to which they have met standards before they enter teaching. The total number of teachers employed in North Carolina declined by 5% between 2009 and 2018, largely due to budget cuts.U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.) Occupational employment and wage statistics. Over the same period, enrollment in traditional public schools and charter schools has increased by 2%,North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. (2009). Highlights of the North Carolina Public School budget, February 2009; North Carolina Department of Public Instruction. (2017). Highlights of the North Carolina Public School budget, February 2017. resulting in larger pupil:teacher ratios.

Teacher Shortages

Even with the reduction in the size of the teacher workforce, the state continues to experience difficulties recruiting and retaining qualified teachers. Many schools are unable to staff their positions appropriately. The state reported 1,621 teacher vacancies for the 2017–18 school year.Public Schools of North Carolina, State Board of Education, Department of Public Instruction. (2018). Report to the North Carolina General Assembly, 2017–2018 state of the teaching profession in North Carolina [Report #70] (accessed 08/01/18). Notably, the most severe shortages were in high-poverty counties.Public Schools of North Carolina, State Board of Education Department of Public Instruction. (2018). Report to the North Carolina General Assembly, 2016–2017 state of the teaching profession in North Carolina. (p. 24, Table 12).

While many positions are left unfilled, others are filled by substitutes or by recruits who have not been prepared for teaching. The proportion of teachers in North Carolina who were not fully licensed more than doubled between 2011 and 2017, from 3.7% to 7.6%, and underprepared teachers were inequitably distributed throughout the state. Whereas 92% of teachers were fully licensed overall, only 80% of teachers were fully licensed in high-poverty schools.LPI analysis of North Carolina Department of Public Instruction data sets.

As the number of teachers in the workforce has declined, so has the supply of credentialed individuals. The total number of credentials issued decreased by 30% between 2010–11 and 2015–16 (from 6,881 to 4,820), with the number of credentials awarded to both in-state and out-of-state teachers shrinking.2017 Title II Reports. (n.d.). North Carolina Section I.g Credentials Issued. Report retrieved from https://title2.ed.gov.

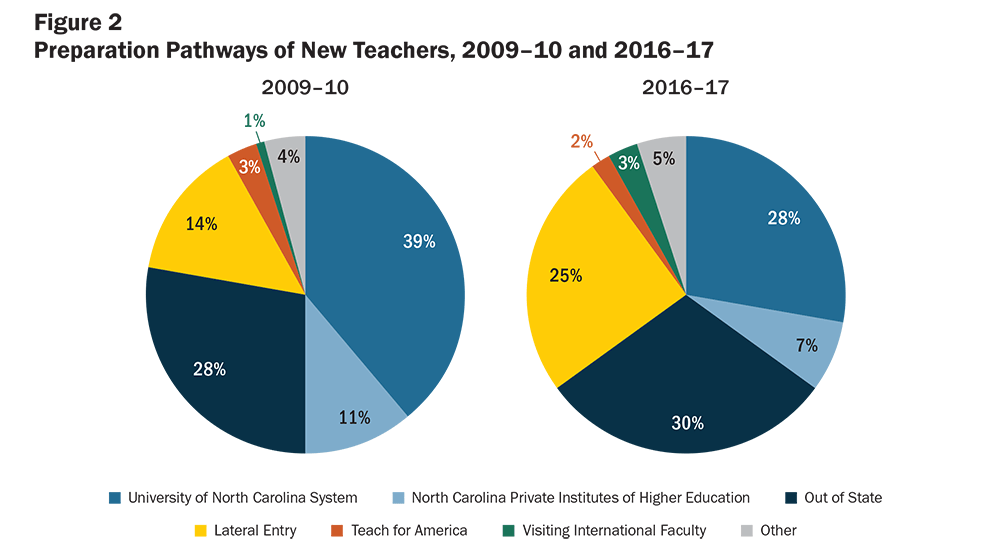

Enrollments in traditional teacher education programs declined by more than 50% between 2008–09 and 2015–16, whereas enrollments more than tripled in alternative preparation programs not based in institutes of higher learning between 2010–11 and 2015–16.2017 Title II Reports. (n.d.). North Carolina State Enrollment Information. Report retrieved from https://title2.ed.gov. As shown in Figure 2, the largest numbers are in what the state calls its “lateral entry program.” With this program, individuals who have passed a content-area test and have been hired by a district, but who are still completing their coursework toward an education credential, can begin teaching immediately upon hire. However, these alternative-route candidates do not appear to graduate and become credentialed at high rates. Candidates in traditional programs, in contrast, represent just over half of enrollees (54%) in credential programs but 76% of all completers.LPI analysis of 2017 Title II Reports. (n.d.). North Carolina State Completer Information. Report retrieved from https://title2.ed.gov.

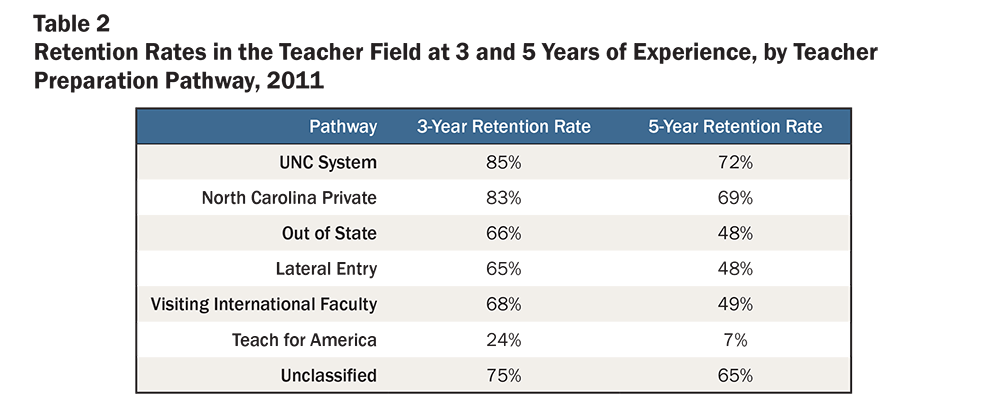

These changes in the sources of teacher supply are important because there are notable differences in the effectiveness and retention of teachers from these different pathways. Studies have found that North Carolina–prepared teachers are generally significantly more effective than those prepared out of state.Henry, G. T., Purtell, K. M., Bastian, K. C., Fortner, C. K., Thompson, C. L., Campbell, S. L., & Patterson, K. M. (2014). The effects of teacher entry portals on student achievement. Journal of Teacher Education, 65, 7–23; Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2007). How and why do teacher credentials matter for student achievement? [NBER Working Paper w12828]. National Bureau of Economic Research. Further, lateral-entry teachers are significantly less effective than teachers who have been prepared before entry. Candidates prepared in the University of North Carolina (UNC) system stay in teaching at much higher rates than those from any other pathway, and lateral-entry teachers leave at much higher rates than those in other pathways.Henry, G. T., Purtell, K. M., Bastian, K. C., Fortner, C. K., Thompson, C. L., Campbell, S. L., & Patterson, K. M. (2014). The effects of teacher entry portals on student achievement. Journal of Teacher Education, 65, 7–23.

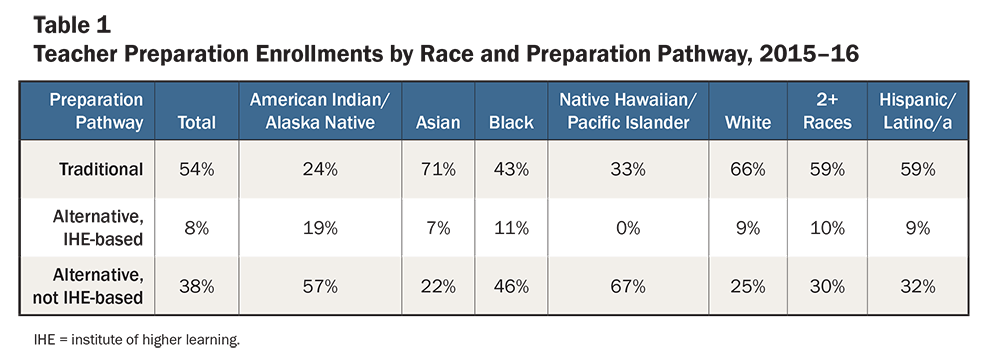

Teachers of Color

After a severe drop between 2012 and 2013, more teachers of color enrolled in preparation pathways, constituting about 30% of all enrollees in 2015–16. However, many candidates of color (Native American, Black, and Pacific Islander) disproportionately enrolled in alternative pathways. (See Table 1.) This placed them at greater risk for failing to receive a credential and, if they did become credentialed teachers, at greater risk for leaving the school or the profession, as both national and North Carolina data show.Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Learning Policy Institute.

Some studies have identified the positive impacts of having a same-race teacher on the long-term education achievement and attainment of students of color, particularly for Black students.Dee, T. (2004). Teachers, race, and student achievement in a randomized experiment. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 86(1), 195–210; Egalite, A. J., Kisida, B., & Winters, M. A. (2015). Representation in the classroom: The effect of own-race teachers on student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 45, 44–52. Several studies in North Carolina have found similar positive effects on Black students’ achievement, attendance, and social-emotional welfare as a result of having Black teachers. Both Black and White students experienced fewer suspensions and expulsions with Black teachers.Gershenson, S., Hart, C. M. D., Lindsay, C. A., & Papageorge, N. W. (2017). The long-run impacts of same-race teachers [IZA Discussion Paper No. 10630]. IZA Institute of Labor Economics; Holt, S. B., & Gershenson, S. (2015). The impact of teacher demographic representation on student attendance and suspensions [IZA Discussion Paper No. 9554]. IZA Institute of Labor Economics; Lindsay, C. A., & Hart, C. M. D. (2017). Exposure to same-race teachers and student disciplinary outcomes for Black students in North Carolina. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(3), 485–510.

Teacher Distribution, Attrition, and Mobility by Pathway

Overall, North Carolina data point to a steep decline in the proportion of teachers who are generally more effective and are most likely to stay in teaching. North Carolina teachers are noticeably more likely than other teachers nationally to plan to leave teaching as soon as possible—and rates have increased in recent years.Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Learning Policy Institute.

The UNC Educator Quality Dashboard shows that teachers who entered teaching through the UNC system’s teacher preparation program had the highest retention rates in North Carolina schools after 3 and 5 years: As of the 2016–17 school year, 85% were still teaching in the state after 3 years and 72% after 5 years. Graduates from North Carolina private institutes of higher education (IHEs) are close behind. (See Table 2.) However, the share of new teachers prepared in these pathways dropped from 39% and 11%, respectively, in 2009–10 to 28% and 7% in 2016–17. (See Figure 2).

Lateral-entry teachers—who have been found to have a significant negative effect on student achievement—are a large and growing share of all teachers in North Carolina.Clotfelter, C. T., Ladd, H. F., & Vigdor, J. L. (2010). Teacher credentials and student achievement in high school: A cross-subject analysis with student fixed effects. Journal of Human Resources, 45(3), 655–681. In 2016–17, they constituted 25% of all new entrants in the state. Furthermore, 53% of these alternative-entry teachers worked in high-poverty schools.Education Policy Initiative at Carolina conducted this analysis of North Carolina Department of Public Instruction data sets based on a request by LPI. Research points to significantly higher attrition rates for alternative-entry teachers. Among North Carolina teachers entering through lateral-entry pathways from the 2005–06 school year through the 2008–09 school year, about two thirds stayed for 3 years, and just under half stayed for 5 years. Teach for America teachers had the lowest 3- and 5-year retention rates. Just 24% were still teaching in North Carolina after 3 years, and only 7% remained after 5 years.

High attrition rates have noticeable effects on student learning both because of the disruption they cause and because they typically reduce levels of teacher experience, which positively influence achievement.Podolsky, A., Kini, T., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). Does teaching experience increase teacher effectiveness? A review of the research. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 4(4), 286–308; Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4–36. The pathways that are associated with considerable churn in their schools are, unfortunately, the ones that have been growing in North Carolina.

North Carolina higher-education institutions have had a key impact on teacher effectiveness and retention. Yet enrollment in the UNC system declined by over 10% overall between 2009 and 2017 and by more than 30% between 2001 and 2017.University of North Carolina System. (n.d.). Stats, data, and reports. As with the total enrollment of teacher candidates in the UNC system, the enrollment of students of color in UNC teacher preparation programs also declined from 2008 to 2017. This enrollment loss (about 33% from 2009 to 2017 for African American students) was significantly greater than the systemwide decline during the same period. Further, teacher production dropped more precipitously at UNC system minority-serving institutions than in the system overall—by 61% between 2011–12 and 2015–16. Production ticked up in 2016–17 but was still less than half of what it was in 2011–12.North Carolina Department of Public Instruction; UNC System Office; Educational Policy Initiative at Carolina, UNC.

Future Teacher Demand

The state must address not only its current vacancy problems due to high attrition but also its future needs. The North Carolina Department of Commerce estimated that the total number of teachers in k–12 schools—i.e., the projected demand—would grow 4.6% between 2017 and 2026.North Carolina Department of Commerce. (n.d.). 2026 North Carolina employment projections summary. (accessed 08/01/18). Overall, the total number of position openings, accounting for teachers who would need to be replaced, was expected to be 72,452 by 2026. As is true nationally, nearly all this demand is expected to be the result of attrition from the teaching profession. The combination of exits from the state workforce and transfers to non-teaching jobs makes up 93% of this expected additional demand.North Carolina Department of Commerce. (n.d.). 2026 North Carolina employment projections summary. (accessed 08/01/18).

Importantly, although teacher attrition is a problem throughout the state, there is variation within regions and school districts. Teacher attrition rates ranged from 4% in low-poverty districts to 33% in high-poverty districts in the 2017–18 school year, and many low-performing schools struggled to recruit teachers to fill positions their teachers had left.Public Schools of North Carolina, State Board of Education Department of Public Instruction. (2018). Report to the North Carolina General Assembly, 2017–2018 state of the teaching profession in North Carolina [Report #70]. (accessed 08/01/18). Often, they were able to fill only a few of their positions with North Carolina teachers moving from other districts and thus had to hire beginning or out-of-state teachers who, as discussed above, are less effective than in-state-prepared teachers.

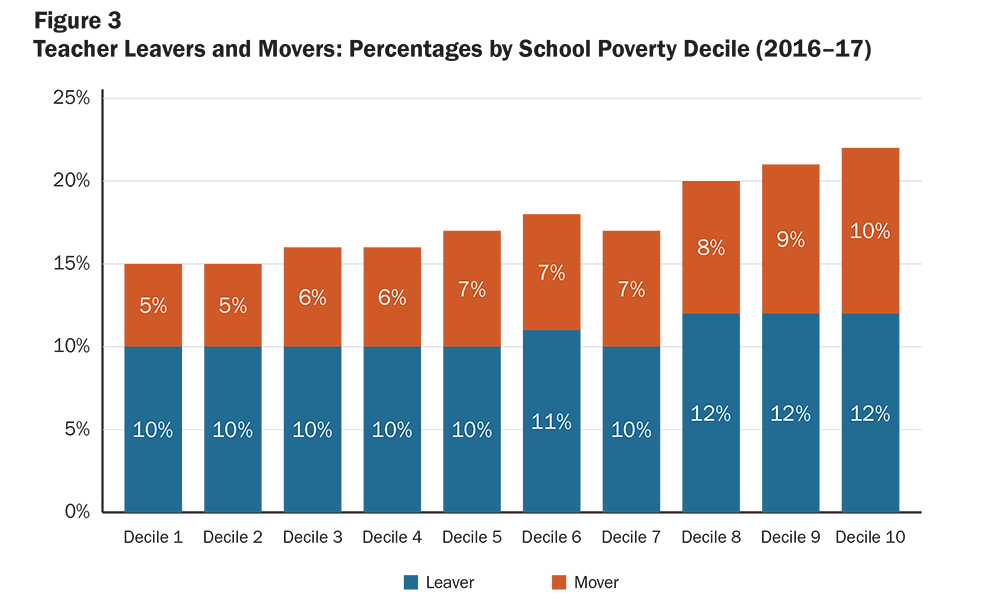

The percentage of teachers moving to a different school was twice as high for teachers in the highest-poverty schools as in the lowest-poverty schools (10% versus 5%). (See Figure 3.)

Current Status of School Leadership in North Carolina

As with teachers, there was a noticeable decrease—about 10%—in the number of school building administrators in North Carolina between 2010–11 and 2011–12. The number has slowly increased, but it remains below the number of school building administrators serving the system in 2008.Public Schools of North Carolina, State Board of Education, Department of Public Instruction. (2009). Highlights of the North Carolina Public School budget, February 2009; Public Schools of North Carolina, State Board of Education, Department of Public Instruction. (2017). Highlights of the North Carolina Public School budget, February 2017. In addition, Education Policy Initiative at Carolina conducted an analysis of North Carolina Department of Public Instruction data sets based on a request by LPI.

However, due to high turnover rates, particularly in some regions of the state, there is a recurring need to fill large numbers of vacancies. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated an 8.7% increase in the overall need for administrators in North Carolina between 2014 and 2024 and a 13.9% increase in the overall need for preschool and child care administrators. Most of this demand (75% and 80%, respectively) will be due to turnover. Meanwhile, the current supply in North Carolina appears limited. Between 2008 and 2016, the UNC system provided a steadily declining number of new principals, producing 56% fewer principals in 2016–17 than it produced in 2009–10 (301 compared with 539). This translated to only 43% of the workforce in 2016–17 compared with a high of 53% in 2010–11.The University of North Carolina System. (n.d.). Stats, data, and reports.

At the same time, the number and share of principals prepared by the Principal Fellows Program also declined with funding cuts. This is important because Principal Fellows are significantly more likely to assume administrative positions immediately after their training and to remain in teaching or administration in the state.Education Policy Initiative at Carolina. (n.d.). UNC analysis of data sets from North Carolina Department of Public Instruction; University of North Carolina System. (n.d.). Stats, data, and reports. More generally, UNC-prepared principals are consistently less likely to leave North Carolina public schools than principals prepared through other routes.

Factors Influencing Teacher and Principal Supply and Quality

When there are high attrition rates, the demand for teachers and principals is inflated—and the quality of educators undermined—by the need to continually replace staff who are leaving at rapid rates. Reducing teacher and principal attrition in favor of a stable workforce comprising well-prepared educators could play an important role in improving student outcomes. Research shows three major factors influencing teacher and principal supply, quality, and turnover: level of preparation and mentoring, compensation, and working conditions.

Level of Preparation and Mentoring

In general, beginning teachers leave at higher rates than experienced teachers, and the extent of the difference has a great deal to do with the preparation and mentoring they receive. Teachers without pedagogical preparation—coursework and clinical preparation for teaching—are two to three times more likely to leave teaching than those with comprehensive preparation.Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., & May, H. (2014). What are the effects of teacher education and preparation on beginning teacher attrition? [Research report #RR-82]. Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania. In addition, new teachers who receive the most intensive mentoring—including in-classroom coaching, support with planning from other colleagues, a reduced teaching load, and principal support—are also twice as likely to stay in teaching as those who receive few supports when they enter teaching.Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., & May, H. (2014). What are the effects of teacher education and preparation on beginning teacher attrition? [Research report #RR-82]. Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania.

Data analysis shows teachers in North Carolina with less experience have high rates of attrition. In 2017–18, 12.5% of teachers with 3 or fewer years of experience left their schools.Public Schools of North Carolina, State Board of Education, Department of Public Instruction. (2019). Report to the North Carolina General Assembly, 2017–2018 state of the teaching profession in North Carolina. Furthermore, preparation for beginning teachers is very uneven in the state; more than 1 in 4 teachers have entered without full preparation, and more than half of these recruits leave the profession within 5 years. Because these teachers are concentrated in high-poverty schools, these schools must meet a continuing demand for teachers associated with the large numbers who leave annually. Another factor influencing high rates of attrition is the lack of mentoring. In 2017–18, fewer than 10% of inexperienced teachers (1,000 out of 15,500 with fewer than 3 years of experience) received services from the state’s current mentoring program.

As with teachers, principals’ professional learning, including preparation programs and in-service supports such as mentoring and coaching, can improve principals’ sense of efficacy and satisfaction and, in turn, improve retention.Darling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (2005). Preparing Teachers for a Changing World: What Teachers Should Learn and Be Able to Do. Jossey-Bass. Studies have found that access to high-quality preparation programs, principal internships, and mentoring significantly reduces the likelihood that principals will leave their schools.Tekleselassie, A. A., & Villarreal, P. (2011). Career mobility and departure intentions among school principals in the United States: Incentives and disincentives. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 10(3), 251–293.

In the 2018 WestEd–LPI survey of North Carolina principals conducted for the Leandro study, about one third of respondents reported feeling their leadership programs prepared them well to lead instruction that helps students develop the higher-order thinking skills that raise achievement on standardized tests. Similarly, only one third felt they had been well prepared to select effective curriculum strategies and materials, and even fewer (29%) felt well prepared to lead instruction that supports implementation of the new standards. More than 1 in 5 responding principals said that they were “poorly” or “very poorly” prepared to lead instruction in these areas.

Compensation

Teachers are more likely to be recruited and retained when salaries or other compensation is competitive.Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. Learning Policy Institute. The amount of debt that teachers accrue during their training is also a factor that affects whether individuals will consider professions like teaching that have lower-than-average salaries in the labor market.Staklis, S., & Henke, R. (2013). Who considers teaching and who teaches? First-time 2007–08 bachelor’s degree recipients by teaching status 1 year after graduation [NCES 2014-002]. U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; U.S. Department of Education. (2015). Web tables: Trends in graduate student financing: Selected years, 1995–96 to 2011–12.

After increasing for many years as part of a campaign to reach the national average, teacher compensation began falling in North Carolina after 2008, losing ground against both national benchmarks and the salaries in southeastern states. In the 2017–18 school year, the average starting salary of a beginning teacher in North Carolina was 29th in the nation at $37,631 versus the national average of $39,249.The Starting Teacher Salary data are obtained from a variety of sources, including National Education Association state affiliates, state departments of education, school district and local affiliate websites, and from http://www.nea.org (accessed 04/01/19). The state’s average teacher salary ranked 34th in the nation and was 18% lower than the national average ($51,231 versus $60,477).Data were updated for this 2022 brief. See: National Education Association. (2019). Rankings of the States 2018 and Estimates of School Statistics 2019 (Table B-6, p. 28). (accessed 11/08/21). Because of teacher supplements—which range from close to $0 to more than $8,000—salaries vary widely across the state for teachers at all levels of experience.

Salaries also matter to principals in choosing new positions and in deciding whether to stay.Akiba, M., & Reichardt, R. (2004). What predicts the mobility of elementary school leaders? An analysis of longitudinal data in Colorado. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 12(18); Ni, Y., Sun, M., & Rorrer, A. (2015). Principal turnover: Upheaval and uncertainty in charter schools? Educational Administration Quarterly, 51(3), 409–437. Studies examining the relationship between principal turnover and compensation have observed principals moving to positions with higher salaries.Akiba, M., & Reichardt, R. (2004). What predicts the mobility of elementary school leaders? An analysis of longitudinal data in Colorado. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 12(18); Baker, B. D., Punswick, E., & Belt, C. (2010). School leadership stability, principal moves, and departures: Evidence from Missouri. Educational Administration Quarterly, 46(4), 523–557; Grissom, J. A., & Bartanen, B. (2019). Principal effectiveness and principal turnover. Education Finance and Policy, 14(3), 355–382; Ni, Y., Sun, M., & Rorrer, A. (2015). Principal turnover: Upheaval and uncertainty in charter schools? Educational Administration Quarterly, 51(3), 409–437; Tran, H., & Buckman, D. G. (2017). The impact of principal movement and school achievement on principal salaries. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 16(1), 106–129. Dissatisfaction with salary is further exacerbated by, in some contexts, principal salaries being lower than experienced teacher salaries despite principals’ additional responsibilities and time commitments.Doyle, D., & Locke, G. (2014). Lacking leaders: The challenges of principal recruitment, selection, and placement. Thomas B. Fordham Institute; Goldhaber, D. (2007). Principal compensation: More research needed on a promising reform. Center for American Progress. This serves as a disincentive for qualified educators to move to leadership positions. A new policy introduced in the 2017–18 school year increased salaries overall but tied annual compensation for principals to student test score gains and their schools’ student populations.In 2019, North Carolina added an incentive for principals who have persistently achieved high growth in their schools to receive a $30,000 annual salary supplement to move to a low-performing school for up to 3 years (up to a $90,000 total supplement). This change has had an uneven impact on principal salaries. Hold harmless provisions ensuring that no principal’s salary is reduced have been renewed annually. Without these in place, some principals would have earned less than they previously had.

In 2017, the average principal salary in North Carolina was $27,206 less (28%) than the national average and the lowest among the southeastern states.Data were updated for this 2022 brief. See: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2017). Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) survey (accessed 11/08/21). In the WestEd–LPI principal survey, nearly 1 in 4 responding principals (24%) identified compensation as the major factor that would cause them to leave their positions in the next 3 years. When asked about North Carolina’s newly enacted compensation policy, which eliminated consideration of experience in favor of pay based on school performance, 44% of responding principals reported that they “oppose” or “strongly oppose” the policy.

Working Conditions

Working conditions influence teacher retention more than recruitment and are a significant factor in determining whether teachers who have left teaching will return. They can include tangible physical conditions, such as safety, physical plant conditions, pupil loads, and the availability of supplies and equipment, as well as workplace efficacy conditions, such as input into decision-making, opportunities for coaching and collaboration, administrative supports, and the collegiality of the environment.Horng, E. (2009). Teacher trade-offs: Disentangling teachers’ preferences for working conditions and student demographics. American Educational Research Journal, 46(3), 690–717; Podolsky, A., Kini, T., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2019). Does teaching experience increase teacher effectiveness? A review of the research. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 4(4), 286–308. The data are quite clear that working conditions, which include teachers’ heroic attempts to address the many stresses that children and families experience in low-income communities, are much worse in many high-poverty schools and contribute to teacher turnover.Berry, B., Bastian, K., Darling-Hammond, L., & Kini, T. (2019). How teaching and learning conditions affect teacher retention and school performance in North Carolina. Learning Policy Institute.

Research has also identified a variety of working conditions that influence principals’ decisions about whether to stay in their positions. These include workload; job complexity; disciplinary environment; the availability of school resources; relationships with students, families, teachers, and district administrators; and the support provided by the central office.Béteille, T., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2012). Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes. Social Science Research, 41(4), 904–919; Burkhauser, S., Gates, S. M., Hamilton, L. S., & Ikemoto, G. S. (2012). First-year principals in urban school districts: How actions and working conditions related to outcomes [Technical report]. RAND Corporation; Farley-Ripple, E. N., Raffel, J. A., & Welch, J. C. (2012). Administrator career paths and decision processes. Journal of Educational Administration, 50(6), 788–816; Fuller, E. J., Young, M. D., Richardson, M. S., Pendola, A., & Winn, K. M. (2018). The pre-K–8 school leader in 2018: A 10-year study. National Association of Elementary School Principals; Tekleselassie, A. A., & Villarreal, P. (2011). Career mobility and departure intentions among school principals in the United States: Incentives and disincentives. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 10(3), 251–293.

Recommendations

This study found that although the state currently faces severe teacher and leader shortages, North Carolina once had a robust system for developing and supporting its educator workforce. Today’s shortages and high turnover—particularly in high-poverty schools—are a function of uneven preparation and mentoring, inadequate compensation, and poor working conditions. Part of the solution to the state’s current problems is to restore key elements of the system that will provide a robust pipeline of well-prepared teachers and leaders trained in North Carolina programs; support their ongoing learning; and recognize their talents through adequate and equitable compensation, access to high-quality preparation and mentoring, and the ready availability of professional learning in the form of professional development and coaching.

This study produced a set of recommendations to strengthen the teacher and principal workforce, many of which were incorporated into North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan, developed by the state and approved by the Leandro court in June 2021.Leandro v. State, Comprehensive Remedial Plan submitted by state defendants (March 15, 2021); Leandro v. State, Order on Comprehensive Remedial Plan (June 7, 2021). The Comprehensive Remedial Plan identifies broad programs, as well as some discrete action steps and associated goals to be reached by 2030—all to ensure that every child is provided the opportunity to obtain a sound basic education in a public school.

Strengthening the Teacher Workforce

1. Increase the pipeline of racially and ethnically diverse, well-prepared teachers committed to teaching in North Carolina public schools who are incentivized and supported to teach in high-poverty communities.

- Rebuild capacity within North Carolina’s public and private universities to increase the number of teacher graduates, with a goal of returning to former levels of production within 5 years. A goal of increasing production from 3,300 to 5,000 teachers who are trained and credentialed in state annually would be appropriate. In addition to incentives for candidates, this may require funds to redesign or rebuild programs that have been weakened. Minority-serving institutions should be a special focus for expansion.

- North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan includes the goal of North Carolina public and private educator preparation programs preparing 5,000 teachers per year by 2030.

- Expand and redesign the current North Carolina Teaching Fellows program, providing targeted incentives for high-need fields and communities, with a goal of increasing the number of candidates from 200 to 1,000 within 3 years and to 2,000 within 5 years.

- North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan includes the goal of selecting 1,500 North Carolina teacher fellows per year by 2030.

- Design and seed teacher residency programs in high-need rural and urban districts through a state matching grant program. Teacher residencies have been successful in many states at solving teacher shortages by providing candidates with high-quality preparation that includes a full year of postgraduate clinical training in a university–district partnership program tied to financial support, a credential at the end of the year, and a commitment to remain teaching in the district for 3 to 5 years.

- North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan includes the goal of each rural and urban school district having access to a high-quality residency program by 2030 that provides support for faculty advising, teacher tuition and stipends, and ongoing induction.

- Expand Grow Your Own (GYO) programs, especially as a strategy to build the supply of teachers who are committed to staying in rural and high-poverty schools. GYO teacher preparation programs recruit and train local community members, career changers, paraprofessionals, after-school program staff, and others currently working in schools. Local graduates and community members offer a sustainable solution to teacher shortages while often increasing the diversity of the teacher workforce.

- North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan includes the goal of each high-need school district having access to high-quality teacher recruitment and development programs by 2030. This includes GYO programs to attract and prepare high school students, teacher assistants, and career professionals.

2. Increase and equalize compensation, addressing teachers’ needs (including salary and, in high-need schools, housing, child care, loan repayment, and retention bonuses).

- Raise and equalize salaries so they are more competitive with surrounding states and other professions. As was done in the 1990s, set a goal and a framework to increase beginning teacher salaries to the national average over the next decade, with concomitant increases in the rest of the salary schedule.

- North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan includes a goal of teacher salaries being competitive with other states and with other career options that require similar levels of preparation, certification, and experience by 2030.

- Add financial incentives for recruitment and retention that bring qualified teachers to high-need communities.

- North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan includes a district-level grant program focused on the implementation of multiyear recruitment bonuses for certified teachers who commit to teach in a low-wealth or high-need district or school for multiple years.

- Leverage the expertise of National Board Certified Teachers (NBCTs) to go to and stay in high-poverty schools and to serve as mentors and instructional leaders. The state could consider an additional multiyear stipend for NBCTs who teach in high-poverty schools.

3. Ensure new teachers receive strong preparation for current needs and mentoring from capable, well-trained mentors to increase retention and effectiveness.

- Use licensing and accreditation rules, which guide what programs provide and what candidates must learn, plus improvement grants to programs to leverage strong clinical training and learning for standards-based, culturally responsive, trauma-informed teaching that can attend to students’ social, emotional, and academic development.

- Expand the North Carolina New Teacher Support Program so that it can support all new teachers. Currently, just 1,000 of approximately 15,500 North Carolina teachers with fewer than 3 years of experience are served. Also, require greater levels of mentor support and training for teachers of record who are not yet fully licensed, ensuring that they get access to the professional development and induction support they need.

- North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan includes a goal of implementing high-quality, comprehensive mentoring programs for all novice teachers by 2030, beginning in 2022, with the goal of the New Teacher Support Program providing comprehensive induction services to beginning teachers in low-performing, high-poverty schools. The state will fund the full cost of this program for beginning teachers.

4. Address teaching and learning conditions that affect retention, including professional learning opportunities and whole child supports.

- Invest in principal professional learning that prepares principals to cultivate collaborative working environments, and invest in teacher-led learning and professional development, which have a strong impact on teacher effectiveness and retention.

- Develop a cadre of teacher leaders across the state who can facilitate teacher-led professional learning and coaching with their colleagues, in person and virtually.

- Create university and pre-k–12 partnerships to support content-focused, standards-based professional learning that is aligned with preservice efforts and available virtually as well as on-site.

- North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan includes a goal of all school districts implementing differentiated staffing models that include advanced teaching roles and additional compensation by 2030.

Strengthening the Principal Workforce

- Expand high-quality pipelines and training that supports entry and retention.

- Expand the North Carolina Principal Fellows Program, which has a 25-year track record of success preparing principals who have been found to be effective and who are more likely both to take principalships when they receive their credentials and to remain in their positions.

- Support candidates’ ability to participate in high-quality preparation programs like North Carolina State University’s Educational Leadership Academy and the Transforming Principal Preparation program and expand their capacity, ensuring that they provide a residency or internship working alongside an expert principal and that both the residency and the aligned coursework provide support to principal candidates in learning how to design schools for student and teacher learning.

- North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan includes provisions to expand access to high-quality principal preparation. For example, a year 2030 goal is to prepare 300 new principals each year through the Principal Fellows Program and the Transforming Principal Preparation program.

2. Update preparation and professional development to meet current needs.

- Use licensing and accreditation levers, plus improvement grants to programs and professional development funding, to leverage strong principal learning for standards-based, culturally responsive, trauma-informed leadership that can attend to social, emotional, and academic development, including leadership on community school approaches that can support success in high-poverty schools.

- Ensure, through preparation and professional development, that principals are prepared to create collaborative learning environments for teachers, which can enhance effectiveness and stem turnover in the teaching force.

- Create mentoring, induction, and coaching opportunities for the existing principal workforce, as some states have done.

- North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan includes a 2030 goal of creating a statewide program to provide professional learning opportunities and ongoing support for assistant principals and principals, beginning with the launch of a School Leadership Academy.

3. Rationalize and improve principal compensation and evaluation.

- Revise the principal salary structure so that it ensures an adequate level of compensation competitive with other jobs requiring similar skills and training; provides a more dependable set of expectations for compensation; and creates incentives, rather than disincentives, for working in high-need schools.

- Consider additional compensation incentives to offset disincentives that may have been created by the elimination of retiree health benefits and pension benefits for leaders hired after 2021.

- North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan calls on the state to implement a statewide school administrator salary structure that will provide appropriate compensation and incentives to enable high-need schools and districts to recruit and retain well-qualified school administrators.

Conclusions

The study findings and recommendations have helped the state create a comprehensive road map for both excellence and equity for every public school student—and for the teachers and administrators who serve them every day. The road map outlines actions, consistent with our study findings, that the state will take to comply with its constitutional obligation to provide every North Carolina child with a sound basic education. In June 2021, the Leandro court approved North Carolina’s Comprehensive Remedial Plan and ordered that the plan “be implemented in full and in accordance with the timeline set forth therein” (i.e., to enable full implementation by 2028 with the objective of fully meeting the state’s Leandro obligations by the end of 2030).Leandro v. State, Order on Comprehensive Remedial Plan (June 7, 2021). The findings of this study can continue to guide policymakers and educators in North Carolina as they work to implement the plan and ensure that all children in the state are afforded a sound basic education.

Educator Supply, Demand, and Quality in North Carolina: Current Status and Recommendations (research brief) by Linda Darling-Hammond, Kevin C. Bastian, Barnett Berry, Desiree Carver-Thomas, Tara Kini, Stephanie Levin, and G. Williamson McDiarmid is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Spencer Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, and Sandler Foundation. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.