Supporting a Strong, Stable Principal Workforce: What Matters and What Can Be Done

Summary

Research shows that school functioning and student achievement often suffer when effective principals leave their schools and that principal retention is related to the conditions they experience in five areas: working conditions, compensation, accountability, decision-making authority, and professional learning. A recent NASSP-LPI study examined reasons for principal turnover using a national survey supplemented by focus groups that asked principals about the conditions in their schools and their intentions to leave their positions. This brief summarizes the study findings and suggests specific strategies that districts, states, and the federal government may want to consider to address factors most likely to influence principal mobility.

About the NASSP–LPI Principal Turnover Research Series

The National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP) and the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) are currently collaborating on an intensive research project to identify the causes and consequences of principal turnover nationwide. The purpose is to increase awareness of this issue and to identify and share evidence-based responses that can guide solutions. This brief is the fourth publication in a series. The first, which presents findings from a literature review, covers the known scope of the principal turnover problem and provides a basis for understanding its mechanisms. The second report offers insights from focus groups of school leaders who shared their experiences and expertise on the challenges of the principalship, as well as strategies to address these challenges. The third publication, the report on which this brief is based, summarizes results from LPI and NASSP’s national principal survey and focus groups, which delve deeply into the five focus areas that emerged from the initial research, and suggests policy strategies to increase principal retention. This fourth publication is a brief that provides an overview of the results of the national principal survey and focus groups, along with associated policy strategies.

All the publications in this series are available at www.nassp.org/turnover and learningpolicyinstitute.org/principal-turnover-nassp.

Introduction

They’re not just like a name on a piece of paper. Those are our kids, and so you love them, and you connect with them, and you take on an emotional weight.Middle level principal from Maryland

While many professionals care for students, the role of the principal is uniquely important. Principals typically define a school’s vision and culture, hire and manage teachers, and create long-term strategies to ensure students’ persistence in their studies. As school leaders, principals impact many students, and their influence can be substantial. They play an essential role in teacher retentionCarver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute., student achievementGrissom, J. A., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2015). Using student test scores to measure principal performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 3–28; Dhuey, E., & Smith, J. (2014). How important are school principals in the production of student achievement? Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(2), 634–663; Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2012). Estimating the effect of leaders on public sector productivity: The case of school principals. (NBER Working Paper w17803). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; Coelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109., and graduationCoelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109..

Yet researchers tracking the profession have found that many principals leaveGoldring, R., & Taie, S. (2018). Principal attrition and mobility: Results from the 2016–17 principal follow-up survey first look. (NCES 2018-066). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics.. In the 2016–17 school year, the national turnover rate was 18 percent, with higher percentages among principals in high-poverty schools (21 percent) and cities (20 percent). The consequences can be quite negative. Studies have found that principal turnover can lead to higher teacher turnoverBéteille, T., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2012). Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes. Social Science Research, 41(4), 904–919; Miller, A. (2013). Principal turnover and student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 36, 60–72., which, in turn, is related to lower student achievementRonfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4–36..

To better understand the phenomenon of principal turnover, the National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP) and Learning Policy Institute (LPI) collaborated on a study. This descriptive, mixed-methods study included a national principal survey executed in 2019 in cooperation with WestEd. The NASSP-LPI survey had a response rate of 40 percent and included a stratified random sample of 424 secondary school principals selected to represent U.S. secondary schools by community type, size, percentage of students of color, and percentage of students eligible for the federal lunch program. These principals were also affiliated with NASSP as members, or as school leaders with an active chapter of the National Honor Society or National Junior Honor Society, student leadership programs administered by NASSP. LPI also conducted six focus groups in 2019 with 33 secondary school leaders from 26 states.

The NASSP-LPI survey and focus groups asked principals about their intentions to stay in the principalship, as well as the extent to which they experience conditions that other research has shown to be related to principal retention and turnover. Results of our analyses point to implications for policy and practice at the local, state, and federal levels:

- Survey and focus group responses reflected national concerns about principal turnover.

- In general, larger percentages of principals planning to leave reported concerns related to 1) working conditions, 2) compensation, 3) accountability, 4) decision-making authority, and 5) professional learning.

The brief begins by describing why stable principal leadership matters and then presents the key findings of the NASSP-LPI survey and focus groups. The brief concludes with policy recommendations at the local, state, and federal levels, which stem from the study outcomes.

Stable Principal Leadership Matters

Principals are the second most important school-level factor associated with student achievement—right after teachersLeithwood, K., Louis, K. S., Anderson, S. E., & Wahlstrom, K. L. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. New York, NY: Wallace Foundation; Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership and Management, 28(1), 27–42.. Numerous studies associate increased principal quality with gains in high school graduation ratesCoelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109. and student achievementGrissom, J. A., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2015). Using student test scores to measure principal performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 3–28; Dhuey, E., & Smith, J. (2014). How important are school principals in the production of student achievement? Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(2), 634–663; Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2012). Estimating the effect of leaders on public sector productivity: The case of school principals. (NBER Working Paper w17803). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; Coelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109.. Further, turnover in school leadership can result in a decrease in student achievementBartanen, B., Grissom, J. A., & Rogers, L. K. (2019). The impacts of principal turnover. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 41(3), 350–374. doi: 10.3102/0162373719855044; Henry, G. T., & Harbatkin, E. (2019). Turnover at the top: Estimating the effects of principal turnover on student, teacher, and school outcomes. (EdWorkingPaper 19-95). Providence, RI: Annenberg Institute, Brown University. doi: 10.26300/c7m1-bb67.. This relationship is stronger in high-poverty, low-achieving schools—the schools in which students most rely on education for their future successBéteille, T., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2012). Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes. Social Science Research, 41(4), 904–919. and, unfortunately, the schools in which there is often the highest turnoverBéteille, T., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2012). Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes. Social Science Research, 41(4), 904–919; Goldring, R., Taie, S., & Owens, C. (2014). Principal attrition and mobility: Results from the 2012–2013 principal follow-up survey. (NCES 2014-108). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; Goldring, R., & Taie, S. (2018). Principal attrition and mobility: Results from the 2016–2017 principal follow-up survey first look. (NCES 2018-066). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; Grissom, J. A., & Bartanen, B. (2019). Principal effectiveness and principal turnover. Education Finance and Policy Analysis, 14(3), 355–382; Fuller, E., & Young, M. D. (2009). Tenure and retention of newly hired principals in Texas. Charlottesville, VA: University Council for Educational Administration..

Furthermore, principals’ ability to create positive working conditions and collaborative and supportive learning environments plays a critical role in attracting and retaining qualified teachersHughes, A. L., Matt, J. J., & O’Reilly, F. L. (2015). Principal support is imperative to the retention of teachers in hard-to-staff schools. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 3(1), 129–134; Grissom, J. A. (2011). Can good principals keep teachers in disadvantaged schools? Linking principal effectiveness to teacher satisfaction and turnover in hard-to-staff environments. Teachers College Record, 113(11), 2552–2585; Kraft, M. A., Marinell, W. H., & Yee, D. (2016). School organizational contexts, teacher turnover, and student achievement: Evidence from panel data. American Educational Research Journal, 53(5), 1411–1449.. Teachers cite principal support as one of the most important factors in their decision to stay in a school or in the professionPodolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.. Conversely, principal turnover results in higher teacher turnoverBéteille, T., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2012). Stepping stones: Principal career paths and school outcomes. Social Science Research, 41(4), 904–919; Miller, A. (2013). Principal turnover and student achievement. Economics of Education Review, 36, 60–72., which, in turn, is related to lower student achievementRonfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4–36..

In addition to the burden of principal turnover on students and teachers, the financial implications are significantSchool Leaders Network. (2014). CHURN: The high cost of principal turnover. Hinsdale, MA: Author; Tran, H., McCormick, J., & Nguyen, T. T. (2018). The cost of replacing South Carolina high school principals. Management in Education, 32(3), 109–118.. Schools and districts must devote time and resources (e.g., for recruiting, hiring, onboarding, and professional development) to replace outgoing principals. Covering this expense may necessitate redirecting funds that had been slated for the classroom.

Key Findings

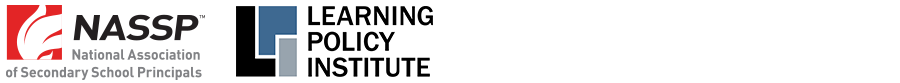

Survey and focus group responses reflected national concerns about principal turnover. More than two in five principals in our survey (42 percent) indicated they were considering leaving their position (Figure 1). Among those considering leaving, 32 percent said they were considering moving to another school, and 19 percent were considering leaving the principalship altogether.

Our focus group participants also discussed challenges in the principalship that they said could feed principal turnover. Members of our study’s six focus groups acknowledged that the principalship was not for everyone and that the work was both important and demanding.

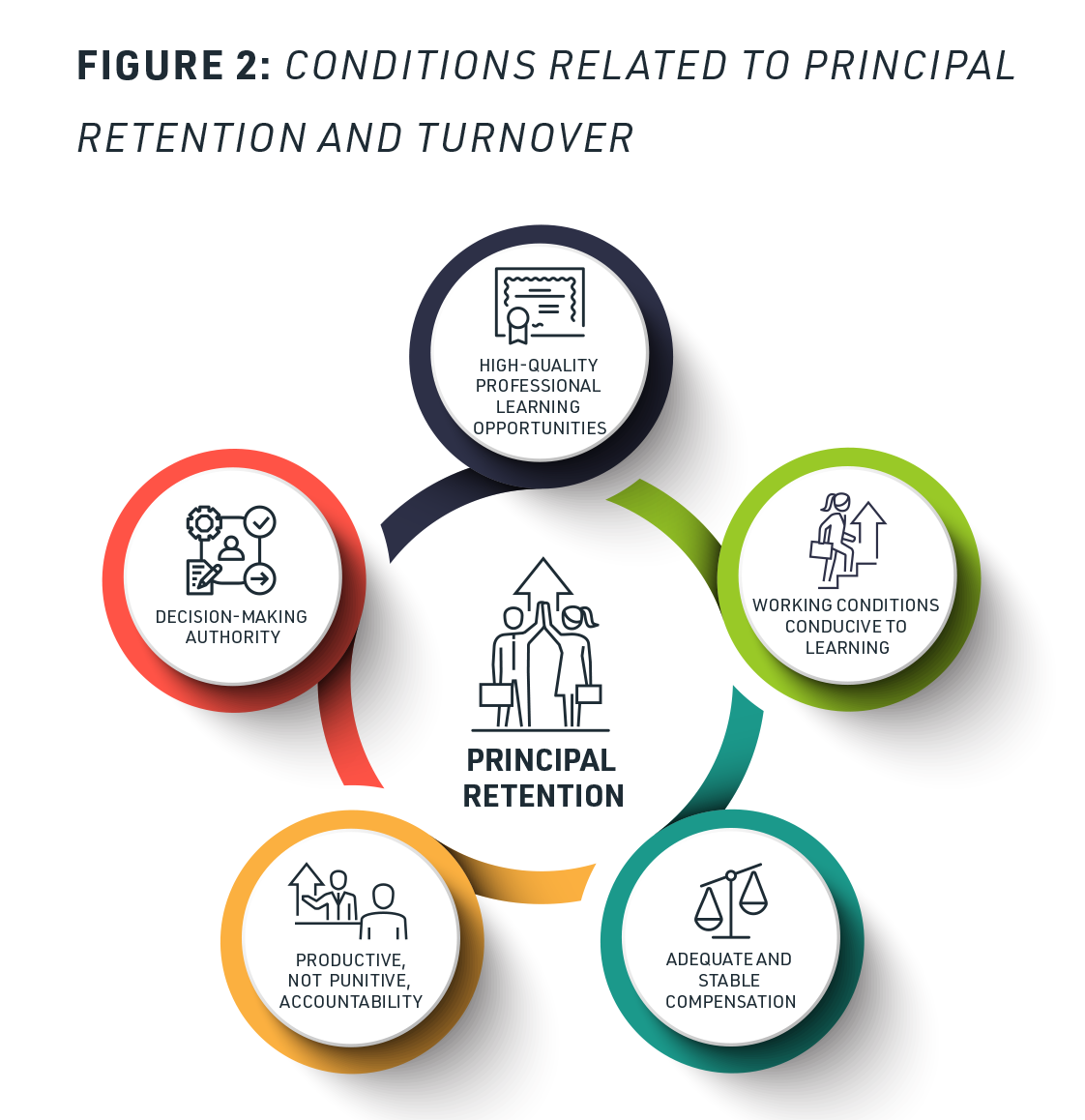

The following sections report on conditions that influence principal turnover in order of concern, as reflected in survey and focus group responses. However, the conditions are highly interrelated (Figure 2). Importantly, while a smaller percentage of principals cited lack of professional learning as a reason for leaving, research suggests that professional learning improves principals’ efficacy and longevity in the jobDarling-Hammond, L., & Bransford, J. (2005). Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; Tekleselassie, A. A., & Villarreal, P. (2011). Career mobility and departure intentions among school principals in the United States: Incentives and disincentives. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 10(3), 251–293..

Working conditions and district supports related to working conditions emerged as concerns. Among principals planning to leave, the two factors identified as most influential were heavy workload (63 percent) and an unresponsive, unsupportive district (51 percent). Additional concerns included districts that have no strategies to retain successful principals, inadequate support personnel to meet student needs, and support from central office not meeting their needs.

Districts figured strongly in principals’ plans: Fifty-three percent of those planning to leave said their districts did not have effective strategies for retaining strong leaders, compared to just 28 percent of those who planned to stay. Similarly, 37 percent of principals planning to leave reported the supports they received from the central office did not meet their needs, compared to 22 percent of principals who did not indicate that they planned to leave.

Principals’ compensation and financial obligations were related to their mobility plans. Principals who planned to leave their schools were more likely to say that they were not fairly compensated for their efforts (42 percent of potential leavers compared to 26 percent of those who planned to stay). Principals planning to leave were also more likely to report student loan debt from principal preparation (41 percent versus 34 percent among those who planned to stay) and from undergraduate or teacher education (32 percent versus 30 percent among those who planned to stay).

Unfortunately, spending personal funds for school materials and supplies added to some principals’ financial stress. Among those planning to leave, 30 percent reported they covered student expenses by purchasing materials and supplies for them, compared to 26 percent of principals who indicated they planned to stay.

High-stakes accountability systems and evaluation practices can discourage some principals. Of principals planning to leave their schools, 31 percent indicated that state accountability measures could influence their mobility decision; even for those not planning to leave, one in five (20 percent) indicated that accountability measures could influence their plans to leave their schools.

Further, more than half of principals planning to leave (53 percent) reported having unconstructive evaluations that did not build their capacity as school leaders, while the percentage was lower among those planning to stay (44 percent). Similarly, well over one-third of those planning to leave (39 percent) reported that they do not trust the results of the evaluation system, compared to 22 percent of those likely to stay in their positions. Principals in our focus groups also discussed their desire for meaningful evaluation and feedback on their work.

A lack of decision-making authority was a concern for some principals. Decision-making authority in most areas was a concern for smaller percentages of principals. Among those planning to leave, over three in 10 (32 percent) reported that they lacked decision-making authority over their schools’ curriculum, while the percentage was slightly lower among principals who planned to stay (27 percent). The percentage was higher for principals serving in high-poverty schools and cities compared to principals in other schools. In addition, almost three-quarters of principals planning to leave their schools (74 percent) reported that they lacked the authority to dismiss poorly performing staff, compared to 64 percent of those intending to stay.

Many principals reported facing obstacles to professional learning opportunities. Principals reported that they had encountered obstacles accessing high-quality principal preparation, and research shows these programs are associated with principal retention. The most commonly cited obstacle was cost: Twenty-seven percent of those planning to leave versus 19 percent of all others identified preparation program costs as a hurdle to accessing principal preparation.

Lack of easy access to in-service professional development could also be an impediment. Among all principals, obstacles cited included lack of time (75 percent), lack of money (36 percent), inability to secure coverage (32 percent), and lack of relevant content (15 percent).

Almost all surveyed principals (98 percent) indicated a desire for additional professional development. The most frequent requests were for professional development to support students’ social-emotional development (82 percent) and physical and mental health (80 percent), to lead schools to improve student achievement (78 percent), to use school and student data to inform continuous improvement (77 percent), and to develop students’ higher-order thinking skills (76 percent).

Larger percentages of principals serving in high-poverty schools and cities reported some of the circumstances associated with principal turnover. Principals from high-poverty schools were most likely to report challenges such as lack of personnel to support students’ well-being (59 percent versus 39 percent for all principals), unfair compensation (46 percent versus 32 percent), having to purchase supplies for their students (46 percent versus 38 percent), and lacking decision-making authority over their schools’ curriculum (44 percent versus 29 percent).

Principals from cities were most likely to report that their districts did not use effective strategies to retain principals (47 percent versus 38 percent for all principals) and that the cost of professional development was an obstacle (51 percent versus 36 percent).

Implications for Policy and Practice

At the local level, policymakers should develop plans to support principals and retain effective leaders by finding out what they most need to support students and manage working conditions; supporting adequate compensation; creating helpful mechanisms for feedback, evaluation, and mentoring; and providing useful professional development. These plans could include advancing policies that:

- Support and retain effective principals by attending to their working conditions and school needs. Working conditions and district supports emerged as key concerns for principals in our study, especially those considering leaving. While each school and district has a different context, our study suggests that district leaders should be alert to principals’ workloads and seek to ensure, to the extent possible, that school administrative teams are appropriately staffed and supported to meet students’ needs as well as staff needs. Further, central office policies should be responsive to principals, which may require increasing the information gathered from principals and collecting more principal input on district decisions that impact schools. This responsiveness should include strategies to keep effective principals, such as providing recognition, needed school resources, or more fiscal flexibility for successful principals.

- Support adequate and equitable principal compensation. Our study showed that many principals found principal compensation inadequate and that those planning to leave were most likely to report this problem, often exacerbated by the problem of student debt from their preparation programs. In addition, our focus groups noted that principal salaries have not always kept pace with teacher salaries, especially when accounting for principals’ greater workload. Given the prevalence of these concerns, district leaders should review the competitiveness of salaries and consider other forms of compensation (such as student loan repayment or housing supports) that may be important to attracting and retaining principals.

- Create or sustain helpful mechanisms for principal feedback, evaluation, and mentoring. Among surveyed principals who planned to leave, more than half reported their district’s evaluation system was not useful. As explained by our focus group participants, principals want timely feedback that they can use to improve their performance and support student learning. Other research suggests that districts that support, develop, and mentor principals can reduce the likelihood that principals will leave their schools or the professionDavis, S., Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M., & Meyerson, D. (2005). Review of research. School leadership study: Developing successful principals. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Educational Leadership Institute; Tekleselassie, A. A., & Villarreal, P. (2011). Career mobility and departure intentions among school principals in the United States: Incentives and disincentives. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 10(3), 251–293.. District leaders can examine the usefulness of their principal support and evaluation systems, gathering input from principals as well as others in the district and community, with an eye toward sustaining practices that are helpful and creating new mechanisms and supports as needed.

- Provide principals with appropriate agency and support in decision making. Some principals who planned to leave indicated that lack of autonomy in making decisions was related to their decision to leave. While most principals reported adequate authority over budget and hiring, more than two-thirds of all principals and three-quarters of principals considering leaving the principalship expressed that it is difficult to dismiss poor-performing or incompetent teachers. To help address this, districts can, for example, support principals with Peer Assistance and Review programs that provide mentors for struggling teachers to help improve their practice and provide due process that can support personnel decisions when they are neededDarling-Hammond, L. (2013). Getting teacher evaluation right: What really matters for effectiveness and improvement. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.. Further, principal training for teacher support and evaluation should be provided, and their input in these types of critical decisions should be sought out and valued by district leaders.

- Remove barriers to principal professional development. Many principals, not just those planning to leave, reported obstacles to in-service professional development, especially lack of time. As districts review principal workload, they should consider time for professional development as essential. District leaders who find that their principals do not have enough time to participate in professional development can consider remedies such as providing district staff support that frees principals’ time; offering professional development at times and locations that are more convenient for principals; and working professional learning into the district feedback, evaluation, and mentoring systems. Districts and schools can use both local funds and federal funds under ESSA (Every Student Succeeds Act), Title II, Part A to address a number of obstacles, including the provision of timely, relevant content, and coverage, if needed, so principals can participate in professional development. Relevant content, according to the principals surveyed, includes professional development in supporting students’ social and emotional development and physical and mental health, and leading school efforts to improve student achievement.

To support these local efforts, state and federal policymakers can:

- Assess and help improve working conditions for principals. Working conditions are a top concern for principals considering leaving. States can support district efforts to assess working conditions and make needed changes. For example, many states gather data about working conditions for teachers through working conditions surveys, district and school report cards, and school improvement plans. Gathering this information for principals as well as teachers and other staff and aggregating it to the state level could help local leaders place their districts within a broader context, correctly identify areas that need improvement, and then make needed adjustments. States could also use the data to determine needs statewide and then target special efforts to the neediest districts and regions. Federal data collection can also assist with these efforts. For example, the National Center on Education Statistics’ principal surveys could expand the type of data collected on principal working conditions. State leaders could then use these data to understand their state’s principal working conditions within a national context and to focus attention on their state’s most pressing needs.

- Support local efforts to improve student supports. As previously described, school principals cite the lack of adequate student support personnel to address the social-emotional and mental health needs of students as a challenge to their work, especially in high-poverty schools. States can make investments in these supports and leverage federal funding under ESSA Title IV, the Student Success and Academic Enrichment Grant program, to address these needs and to enhance resources for students and staff. At the federal level, this program should be fully and consistently funded at its authorized level of $1.65 billion, substantially higher than current funding.

- Enable adequate and equitable principal compensation. In our survey, larger percentages of principals who planned to leave their positions reported that compensation was a factor in their future plans. Notably, principals in high-poverty schools are most likely to find their salaries inadequate. Depending on the extent of local control, state leaders can establish or incentivize more competitive principal salaries across and within districts, or strengthen compensation through other vehicles, such as loan forgiveness or housing supports. States can also revamp their funding formulas to ensure that overall school funding is adequate and equitable, targeting additional funds to the most needy districts and schools, which will help districts provide more adequate compensation, especially in the communities where it is most needed.Tran, H., & Buckman, D. G. (2017). The impact of principal movement and school achievement on principal salaries. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 16(1), 106–129; Papa, F. (2007). Why do principals change schools? A multivariate analysis of principal retention. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 6(3), 267–290.

- Create or expand programs that help underwrite the cost of high-quality principal preparation. A number of principals surveyed described the challenges of carrying a high student debt load from their teacher and principal preparation programs, which exacerbated the problems of inadequate compensation. This is especially true for principals working in high-poverty schools and rural communities. To address this challenge, states can provide funding to cover the cost of high-quality preparation in exchange for a commitment to serve in a high-poverty or rural school. These kinds of programs have been shown to be effective at recruiting doctors, nurses, and teachers, especially when they underwrite a significant portion of educational costs and are bureaucratically manageable for candidates, districts, and higher education institutions.Podolsky, A. & Kini, T. (2016). How effective are loan forgiveness and service scholarships for recruiting teachers? [Policy brief]. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

One example, the North Carolina Principal Fellows Program, provides competitive, merit-based scholarship loans to individuals seeking a master’s degree in school administration and a principal position in North Carolina public schools. In their first year, fellows receive $30,000 to assist them with tuition, books, and living expenses while they study full timeEspinoza, D., Saunders, R., Kini, T., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2018). Taking the long view: State efforts to solve teacher shortages by strengthening the profession. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. . In their second year, they complete a paid internship under the wing of an expert principal while they complete their coursework. As of 2015, 1,300 fellows had completed the program, and nearly 90 percent of principal fellows graduated and completed their four-year service commitmentEspinoza, D., Saunders, R., Kini, T., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2018). Taking the long view: State efforts to solve teacher shortages by strengthening the profession. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. . These types of scholarship programs could be developed and targeted to principals who commit to working in a high-need school.

To support and scale up these state efforts, federal funding under Title II of the Higher Education Act (HEA), the Teacher Quality Partnership Grant program, which supports teacher preparation programs, could be expanded to include school principals. To further support principals’ access to high-quality preparation, the TEACH Grant Program, under Title IV of the HEA, could be expanded to include principals in addition to teachers, covering their costs of preparation in exchange for service. - Support local efforts to develop effective school leaders by increasing state and federal investments in high-quality professional development. As the importance of strong principals has become increasingly clear, more states are increasing their commitments to funding principal professional learning opportunities through coaching, mentoring, and networks as well as through professional development courses, workshops, and conferences. Many states are seizing the opportunity under the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), Title II, Part A to allocate funding to evidence-based professional development, with nearly half of states taking advantage of the optional 3 percent set-aside for principals to invest in principal learningNew Leaders. (2018). Prioritizing leadership: An analysis of state ESSA plans. New York, NY: Author. . Further, ESSA, the most recent version of ESEA, is due for reauthorization in 2020, and its funding to support school principals could be expanded. Increasing overall funding and the set-aside for principals under this title would allow more principals to receive the high-quality preparation and professional development they need to be effective.

For example, North Dakota is using ESSA as an opportunity to create multi-tiered leadership support to develop principals as effective leaders. One tier involves implementation of a leadership academy to ensure that North Dakota principals have the resources and support they need to be effective leaders. The leadership academy will provide professional support, professional development, career ladder opportunities, assistance with administrator shortages, and support to address administrator retention in an effort to raise student achievement. The academy will also serve as a resource for schools designated as in need of improvement pursuant to ESSA, in an effort to promote and build capacity in specific aspects of leadership.North Dakota Department of Public Instruction. (2018, April 30). North Dakota Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) state plan. Bismarck, ND: North Dakota Department of Public Instruction, p. 96.

We are grateful to the National Association of Secondary School Principals for its funding of this brief. Funding for this area of LPI’s work is also provided by the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Stuart Foundation, and the Sandler Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Ford Foundation.