Principal Turnover: Insights from Current Principals

Summary

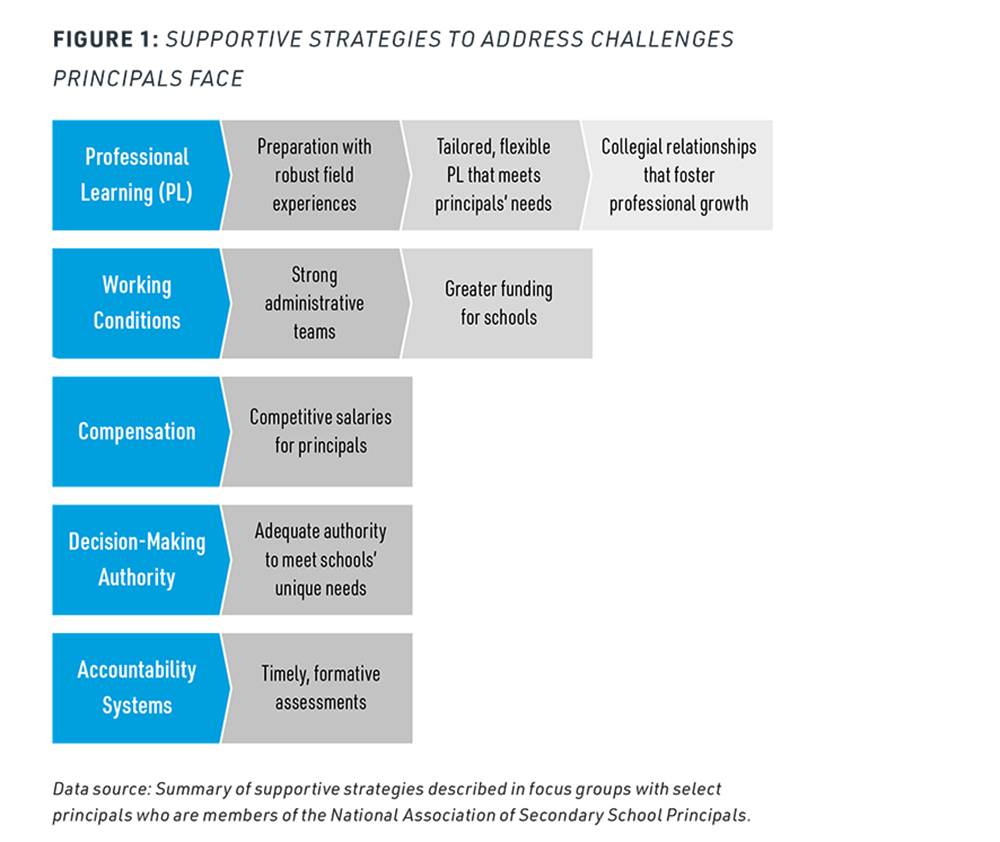

Studies show that school functioning and student achievement often suffer when effective principals leave their schools. Past research has identified five main reasons principals leave their jobs: inadequate preparation and professional development, poor working conditions, insufficient salaries, lack of decision-making authority, and ineffective accountability policies. This study draws on evidence from focus groups to better understand the challenges principals face and highlight strategies that can support principals and increase their retention. Focus group participants identified multiple strategies, including high-quality professional learning opportunities, support from strong administrative teams with adequate school-level resources, competitive salaries, appropriate decision-making authority, and evaluations characterized by timely and formative feedback.

About the NASSP–LPI Principal Turnover Research Series

The National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP) and the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) are currently collaborating on an intensive, yearlong research project to identify the causes and consequences of principal turnover nationwide. The purpose is to increase awareness of this issue, and to identify and share evidence-based responses to help mitigate excessive turnover in the principal profession. This brief is the second in a series. The first, which presented findings from a literature review, covers the known scope of the principal turnover problem and provides a basis for understanding its mechanisms. It also suggests, based on past research, that district and school leaders and federal and state policymakers implement a number of strategies to increase principal retention: Offer effective and ongoing professional development; improve working conditions; provide fair, sufficient compensation; provide greater decision-making authority; and decrease counterproductive accountability practices. This brief builds on that knowledge with insights from focus groups of school leaders who shared their experiences and expertise on the challenges of the principalship, as well as strategies to address these challenges.

In addition to the literature review and focus groups, the yearlong research agenda includes analysis of both the U.S. Department of Education National Teacher and Principal Survey and a national principal survey that will delve deeply into the five focus areas that emerged from the initial research. Findings from the survey will increase the field’s knowledge regarding principals’ mobility decisions. Based on the research, LPI and NASSP will develop recommendations for policymakers at all levels of government to advance policies for states, districts, and schools to support and retain high-quality school leaders.

All the briefs in this series are available at www.nassp.org/turnover and learningpolicyinstitute.org/principal-turnover-nassp.

Introduction

School principals are essential for providing strong educational opportunities and improved outcomes for students. They can do this by enhancing teachers’ practice, motivating school staff, and maintaining a positive school climate. Building these conditions takes time and requires continuity of strong leadership. Consequently, sudden or frequent turnover of effective principals can disrupt school progress, often resulting in higher teacher turnover and, ultimately, lower gains in student achievement.Levin, S., & Bradley, K. (2019). Understanding and addressing principal turnover: A review of the research. Reston, VA: National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Principal turnover is a serious issue across the country. A 2017 national survey of public school principals found that, overall, approximately 18 percent of principals had left their position since the year before. In high-poverty schools, the turnover rate was 21 percent.Goldring, R., & Taie, S. (2018). Principal attrition and mobility: Results from the 2016–17 Principal Follow-up Survey First Look (NCES 2018-066). U.S. Department of Education. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

To increase understanding of principal turnover and determine which policies and practices might stem the tide, the National Association of Secondary School Principals (NASSP) and the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) have partnered to conduct a yearlong study of principal turnover. This effort began with a review of the literature to determine what is already known about the causes of turnover. LPI’s literature review found five main reasons principals leave their jobs: inadequate preparation and professional development, poor working conditions, insufficient salaries, lack of decision-making authority, and ineffective accountability policies.

In the second phase of our research, LPI collected in-depth insights through focus groups with experts—namely, current administrators—who grapple with the everyday, long-term demands and challenges that mark the principalship. Focus groups consisted of 17 participants with diverse backgrounds, representing 15 states and serving in schools with poverty levels ranging from 4 percent to 78 percent. The LPI focus groups explored these same five aspects of principals’ jobs. Notably, we found that focus group participants faced challenges similar to those identified in the literature review. In addition, based on feedback from these administrators, we identified several strategies that could give principals the supports they said they needed to succeed and remain in their schools:

- High-quality professional learning opportunities

- Support from strong administrative teams with adequate school-level resources

- Competitive salaries

- Appropriate decision-making authority within the school context

- Evaluations characterized by timely, formative feedback

Principals' Commitment to Leadership for Students and Teachers

Principals’ comments illustrated how their commitment to their schools motivates many to remain in their positions. Focus group participants voiced a strong dedication to their students and staff, and they described their desire to make a positive difference for students.

Principals spoke of their affection for the students and the pleasure it brings them to be in their world. One high school principal exclaimed, “My favorite thing about being a principal: I love those kids! They’re like … my children.” Describing her students as “passionate and fun and energetic,” a middle level principal said, “Every day kids bring joy … and that keeps you going.” Another middle level principal joked, “I am kind of a middle school kid myself, so that’s the appropriate place for me.”

Principals also discussed enjoying their role supporting teachers and staff so that they, in turn, can create “conditions for students to aspire to their highest aspirations.” A principal commented, “[It’s] a joy to work alongside the new faculty members as they grow professionally.”

For many, the principalship is a calling. One principal explained that her vocation is aligned with her purpose; she asserted, “I believe in what I am doing. I am supposed to be here.” Another principal in a school with a majority of first-generation college-bound students shared that her personal experiences and connection to her community called her to the principalship. Similarly, what seemed most moving for principals was their ability to impact students’ lives. A middle level principal from the Midwest said, “[I] feel like I go home having made a difference every day.” A high school principal from a struggling rural community shared, “I get to work with a lot of students who grew up under the same stars that I did and show them that there’s hope and a way out of what they have been born into.”

The Challenges Principals Face

While principals spoke passionately about their roles, they also acknowledged the complexity and daily demands of the principalship that often make their jobs quite challenging. Focus group participants cited poor working conditions, being undervalued for their work, having too little authority to make certain decisions for their schools, and accountability systems that do not support continuous growth.

Working Conditions

Principals’ working conditions can influence their sense of well-being and hinder their ability to accomplish all they hope to.

Principals face multiple and growing needs from students and parents. Principals spoke of their responsibilities to their students and communities and the stresses that can result. As one put it, being a principal is like having “a weight that you put on your back and you just carry all the time.” Several said the stress of the job is heightened by the emotional burden of supporting students. Principals discussed how the needs of their students have grown over the years due to societal pressures. One principal explained, “Whatever seems to happen outside of the school community, meaning what’s going on with our politics, our country, political agendas, … seems to work its way into the high school.” Principals also told difficult stories of dealing with their students’ trauma, and one acknowledged that “the adults internalize a lot of that trauma”:

I think one year we had five kids who lost someone in the city within a year, and they’re not just like a name on a piece of paper. Those are our kids, and so you love them, and you connect with them, and you take on an emotional weight that’s really hard to compartmentalize.

Effective principals typically build relationships with parents and families to engage them as integral partners in the school.Garbacz, S. A., Hermon, K. C., Thompson, A. M., & Reinke, W. M. (2017). Family engagement in education and intervention: Implementation and evaluation to maximize family, school, and student outcomes. Journal of School Psychology, 62, 1–10. However, several principals called out the need to address the expectations of parents as an added stress. A high school principal of a school serving students from high- and low-income backgrounds shared her experience:

I deal with the gamut. … [T]he affluent parents, they want everything. … They want blood from a stone and they’re expecting you to do it. … Then you have the other ones. … They’re more needy because they have to work three jobs and so forth and so on. They have high expectations for us as well, but they’re looking for different things, different types of support.

Principals said their many obligations can require a huge time commitment, impeding their work-life balance and limiting what they can accomplish on the job. Principals discussed their long work hours. A number spoke of early mornings, some getting up as early as 2:30 a.m. to finish the paperwork that is impossible to get to during the day. A high school principal, seeming to speak for many focus group participants, explained: “It’s not a 9-to-5 job. As soon as you wake up to the time you go to bed and even on weekends. Kids can report things anytime. You’re on call all the time.” As a result of their busy schedules, several principals described how having a balance between family and work is challenging and often requires personal sacrifices. One principal shared that in recent years the only times he and his wife have been out together were during school dances.

With their myriad responsibilities, school leaders said they struggled to find adequate time for their role as instructional leader. A middle level principal from a high-poverty school in the Pacific Northwest acknowledged that the time needed to deal with disciplinary issues, such as inappropriate social media use, meant less time for instructional leadership. He explained, “Carving out the time to be in the classroom and really develop that relationship with the kids and the teachers has become more and more difficult.” Another middle level principal agreed, stating, “All of the other managerial things and the things that take you away [from being] able to get to spend time and develop those that you have in your building [are] more and more of the challenge.”

Insufficient resources make it difficult to create positive learning environments. A number of principals spoke of lacking the appropriate resources to serve their students and teachers. One principal explained what budget cuts meant for her school: “The amount of money … has been cut 75 percent, and last year I had $0 for textbooks.” She also called out the lack of local resources to support students, mentioning lack of mental health resources as an example: “Kids are coming to school with more and more challenges associated with mental health, and there’s nowhere to refer them. You can send them to the hospital for an evaluation; they’re back to school the next day.”

For many, the lack of funding meant that principals spent time advocating for resources from their districts. For some, this was “a full-time job.” A high school principal from a mid-Atlantic state spoke of the time she spent dealing with infrastructure issues that affected the entire school community: “Our fields are kind of falling apart. … [T]hat’s a real struggle. There are endless phone calls about the fields and the air conditioning and the heating and the pipe that collapses.”

Compensation

Focus group participants agreed that compensation levels are rarely commensurate with the time, effort, and skills required of school leaders.

Principal salaries do not fully compensate principals for the time and effort they must spend to do their jobs well. All focus group participants reported that principal salaries are generally inadequate, given the expectations for the role. One middle level principal explained, “You have to be like a CEO of a small company.” She described being “responsible for a thousand people’s children” while “multiple people who don’t have the responsibility make more money than you do.” Other principals pointed out that, although the salary may seem reasonable, if you break it down as an hourly payment, the compensation is actually quite low. A high school principal from Ohio explained: “No one wants to do the math. If you do the [math], the highest-paid teachers in my building make more each day than I do.”

In schools with higher concentrations of students in poverty and fewer resources to serve high-need students, the demand on school leaders can be much greater. One high school principal explained: “[My] district struggles to attract [principals] to begin with. They don’t pay. It’s difficult. I mean they pay, but not to work at a high-needs, high-poverty, inner-city school.”

Teacher salaries can be higher than principal salaries, disincentivizing teachers from becoming principals and principals from remaining in their jobs. Focus group participants said that dissatisfaction with salary is further exacerbated by the fact that, in some contexts, principals’ salaries can be lower than salaries of experienced teachers, despite principals’ additional responsibilities and time commitment. A high school principal spoke of his school district, saying, “[T]he teacher can make more money than the [principal] with a lot less responsibility and the summer off.”

A Northwestern state provides an example of high teacher salaries relative to principal salaries: A recent court action to address an underfunded K–12 school system led to considerably increased teacher salaries. However, principal salaries were stagnant. A principal from this state described the impact: “Now we’ve got teachers making more money than the principals on less time. They’re [employed] only seven months a year, and some principals are looking at that and going, … ‘I don’t need this crap. … I’ll just go back to the classroom.’”

The implications are far-reaching. This principal looked up the numbers of open principal and assistant principal positions and found “probably the largest number [of vacancies] I’ve ever seen at this point in the school year already in [our] state.”

Decision-Making Authority

Principals must make and guide many decisions and processes to ensure success in the complex organization they manage in ways that take into account the contexts in which they work.

Lack of decision-making authority can frustrate principals working to serve the needs of their students and school communities. Principals participating in focus groups were deeply committed to their roles as leaders and discussed feeling responsible for their schools’ destinies. However, many were frustrated by the constraints that limited their ability to make decisions. A middle level principal described himself as being like a manager of a franchise:

You take it from every angle, and you have some decision-making power in terms of which direction your school goes, … but there’s so much that gets cast down from above that you don’t have a say in—where you’re kind of the used car salesman, you have to sell it to your staff and make them think it’s a great idea even if you don’t agree with it.

Others recounted similar stories in which their decisions were overridden by a district’s central office or the local school board. One principal commented: “There’s certain initiatives. … You’re going to spend hundreds and thousands of dollars for an IB [International Baccalaureate] program. I would definitely want a social worker instead of that. There’s some things that you have to do that are not aligned with what you want to do.” Beyond district governance, principals spoke of state and federal policies and mandates influencing issues related to allocation of funds, personnel, and curriculum.

Accountability

Accountability systems can add to the stress many principals face from long work hours, the breadth of roles and responsibilities, and familial responsibilities. Ineffective accountability systems can add extra tasks to principals’ to-do lists and, in some cases, provoke leaders to leave their positions.

Some accountability systems do not accurately measure the quality of schools and leaders. The majority of principals participating in focus groups reported that their districts’ accountability systems were ineffective. Many pointed to the evaluation process as nothing more than a compliance exercise. A high school principal from a suburban community in the Southeast complained: “They’re not even asking us for the evidence. I’d be more than happy to provide evidence of instructional leadership, management, hiring.”

Principals from both high- and low-poverty schools questioned the validity of accountability systems that rely on student assessments that do not reflect student growth. One middle level principal explained:

Schools are demoralized by how [they are] assessed and the way that people who’ve never set foot in a school judge us and slam us. … [There are] amazing teachers working at some really challenging places, and people think that the schools are failing because the kids aren’t doing well on these standardized tests, but really these teachers are growing these kids and doing so many more things. That’s hard.

Other principals pointed out that accountability systems can be misleading when assessments leave no room to demonstrate student improvement or do not account for students who opt out of testing.

Another concern expressed by several principals was that accountability systems can rely on evaluators who are ill prepared for the role. A middle level principal explained:

I think the system is only as good as the person using it. … You can put a 16-year-old in a Ferrari and they’re going to wreck it just the same as they would a Ford Escort. … I’ve had [ineffective] evaluators that’ve done [my evaluation] at 4:00 p.m. the last day of my contract. … I’ve had others that take a real diligent stance on it and give constructive feedback and try to grow you. So, it’s not so much about the system as it is the person working that system.

Principal evaluations are not always designed to help principals improve their practice. Many focus group participants emphasized that their states’ and districts’ accountability systems are not helpful to their development as school leaders. One principal commented that, because his evaluation is not useful, he relies on self-reflection to improve as a leader. Other principals shared experiences in which they wrote their own evaluations on behalf of their evaluators, setting their own goals or comparing their efforts to expectations based on state standards.

Supportive Strategies From Focus Group Participants

As principals discussed challenges, they also highlighted some remedies that help them better serve their schools and stay in the profession.

Professional Learning

To engage successfully in the work of school leadership, principals need an enormous range of knowledge and skills. Continuous learning is required to meet this need.

Principals praised preparation programs that offer robust field experiences with strong mentors and/or internships. A number of principals spoke positively about their preparation programs, specifically calling out robust field experiences that offered comprehensive support from strong mentors and/or internships. For example, a high school principal from an urban community in the Southeast described her preparation program:

I had a wonderful program and a wonderful experience. I had to do my internship for a solid year, and I think I was very fortunate to find the principal mentor that I did, and I think that’s half the battle. Don’t choose the school; choose the principal so that you can truly, truly learn from [someone] who’s going to push you out there and get you the experience you need, somebody that you can build a relationship [with], who’s willing to throw responsibility over to you.

Another high school principal from the Pacific Northwest called his mentor “priceless.”

A few principals described successful district-run programs. These programs also featured strong mentors and internships. For example, a district in the Southeast had developed an Aspiring Principals Residency Academy for individuals seeking to be school leaders. This internship program includes a yearlong residency program. The principal describing this program explained that participants retain their assistant principal roles and remain in their buildings. At the same time, however, program participants devote one day each week to “professional learning, and they have a mentor that develops and creates situations and opportunities … to engage in actual legitimate professional practice as a principal.”

School leaders spoke highly of tailored professional development that provides flexibility to accommodate difficult schedules and meets the needs identified by principals. A number of principals expressed their appreciation for professional development opportunities that fit their schedules and budgets. Other principals suggested that professional development would be more valuable if it helped them address the specific needs and contexts of their schools. A middle level principal from a Mid-Atlantic state praised her district for meeting these requirements:

I think my district does a pretty good job. We have an office of continuing professional development that offers courses that anyone can take: teachers, higher educators, administrators. We have monthly principals’ meetings and quarterly curricular meetings that are a half day that I think are pretty decent. There is also money for administrators that we can apply for. There is $600 allotted for every administrator, and also we each get reimbursed, and then after November 1 whatever is left [in the budget]—this can add [up] to $3,000.”

Some principals also praised districts that give leaders the option to participate in externally provided professional learning. The same middle level principal was able to select her own professional development program. She spoke enthusiastically of online self-paced courses offered at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that both satisfied professional development hour requirements and aligned with her professional needs.

Similarly, one principal said his state supports all its principals with professional development as part of their contract. In fact, the state requires principals to be recertified. The principal explained, “There is an incentive for you to take advantage of professional development because if you don’t, you’ll lose your certificate.”

Formal and informal relationships with colleagues were said to be invaluable for professional growth and support. Many principals expressed deep gratitude for their mentors and colleagues who guided and supported them through new experiences and difficult times. They shared the understanding that these relationships are essential to their professional growth and longevity in the principalship. According to one principal:

It’s a lonely, lonely job, especially when things are not going well or something’s happening. You are the point person. … Phone a friend: You have got to have the ability to have a trusted mentor or someone else that’s across town or in another town that you can call, that can just understand the shoes that you’re walking in.

Connections with colleagues varied based on principals’ paths and contexts. For example, a number of principals recounted maintaining relationships with their early mentors. A novice principal chronicled her relationships with various mentors, stating, “In the last three years, I probably would have been undone were it not for the people who walked through it with me and gave perspective.”

A high school principal from New England explained that her state association connects first-year principals with other principals from around the state. The fact that her mentor was out of her district allowed for “a better level of trust.” She said, “That person has been long retired, and I am still in touch with him on a daily basis.”

While many principals spoke of individual colleagues or mentors they reached out to for support, a few principals stressed the need for organized networks. As two principals respectively described their professional learning communities:

We have a [principal] group that I manage, 16 area high schools, and we meet monthly, and just that networking with other schools where you share best practices. A lot of the sessions are therapy or commiseration sessions, like, “Wow, you’ve got it really bad,” and that makes you feel better about your own school. But we plan it, we organize it, we bring in the speakers, we have a book study, etc. … Our district gives us the green light for that, which is nice. … As you network with other folks, it’s powerful.

I put together a group of principals myself from neighboring towns that came about totally organically. I called three people to ask them about scheduling or some policy or practice or something. And we put together a group that four years later still meets every other month with an agenda. … That’s been my best professional development.

Working Conditions

Principals spoke of the importance of supportive working conditions both for their personal well-being and for maintaining a positive and productive school culture.

A strong administrative team could help balance work and life responsibilities. Focus group discussions indicated that having a strong support system in place can make the principalship much more manageable. A middle level principal who wanted to ensure family time described support she received from a strong assistant principal:

She and I became like family, and then we fiercely protect that for each other. … We agreed from very early on: … “[Y]ou will not miss going to one of your son’s games because I will cover you. I will not miss a play or something at my kids’ preschool because you’ve got me.”

Providing and equitably allocating funds could help ensure that schools are positive learning environments for all students and educators. All principals called on states to provide the necessary dollars for high-functioning schools. While waiting for that to happen, some principals implemented remedies to deal with inadequate funds. For example, a middle level principal serving students from low-income families built community partnerships, saying:

We have to be very creative and very different. … We’re very creative in partnering with the local children’s board of the local government. We work a lot with the school system to build partnerships that actually meet [our] needs. [Also, we] signed up to have summer school and [we] run camps or programs free for our kids over the summer to actually get them what they need.

Another high school principal from a struggling rural community partnered with U.S. Cellular to put Wi-Fi (hotspots) on school buses. Then he used funds from a 21st Century Community Learning Centers grant to cover the expense of having an aide on a bus to help students with their homework. He said, “We put them on every bus that travels more than an hour.” These examples illustrate not only principals’ expressed needs for more adequate funding, but also principals’ resourcefulness in how to use additional funds effectively.

Compensation

Competitive salaries that are aligned with principals’ vast responsibilities and multiple roles could help attract and retain school leaders. A number of principals noted that competitive salaries could attract and retain principals. A high school principal spoke of his appreciation for being in a district that, although serving a high proportion of students in poverty, had the resources to provide a good salary for the principalship. He said, “I wouldn’t go anywhere else in my state because I’d take a massive pay cut if I did, but [my district has] done a good job in making sure that their salaries are competitive.”

Decision-Making Authority

Principals with greater decision-making authority could better implement policies and deploy resources based on their understanding of their schools’ needs. A few principals who had greater authority over personnel issues such as staffing and teachers’ professional development explained how they used their power to serve their schools. They made decisions that helped actualize district policies and targeted staff expertise and resources to their schools’ unique contexts. A middle level principal from a Southeastern suburb spoke about how she determined the professional learning plan for her teachers based on her school’s greatest need. She shared:

There are [district-determined] areas that our [professional learning] plan has to fall under, but within my building I can determine the professional learning I can work on. We’re doing a lot of work with equity, diversity, and shifting of culture.

Accountability

Timely, formative evaluations could help principals set meaningful goals and improve their leadership. Although the majority of principals said their evaluations did not inform their practice, a few spoke highly of certain facets of their accountability systems or offered suggestions to improve the ineffective systems through goal setting and timely, formative feedback.

In an example of the power of goal setting, a middle level principal described the positive experience of setting her own goals aligned to the needs of her students. One goal was to address the disproportionate discipline in her school. Sharing this goal with the teachers and administrators in her building resulted in fairer discipline practices that were enforced more equitably.

Advocating for timely, meaningful feedback, a high school principal from the Southeast suggested that systems include ongoing, real-time feedback, along with opportunities to change practice. He explained, “Consistent feedback in a timely way with a leader has the potential to provide the most opportunity to move the needle.” Another high school principal from the Mid-Atlantic added, “I would be glad to have feedback right after something [happens]. I’ll take it there, but I don’t want it to work against me.”

To increase formative feedback, another principal suggested that teachers be included in the evaluation process: “If we did it right, teachers will be doing a lot of that feedback, [answering the questions:] How’s their [principal’s] communication? Are they trustable? Are they cool under fire? Are they fair?”

Principals in our focus groups clearly valued accountability systems aimed at continuous improvement rather than checking boxes on forms. Their suggestions for timely, formative evaluations could support principal retention, as well as professional growth and overall school improvement.

Conclusion

Principals are uniquely positioned to offer insights into why school leaders might leave their schools for more comfortable and rewarding environments—or abandon the profession altogether. Those we spoke with shared their expertise and helped us better understand the demands and challenges they face every day. Their concerns were consistent with what we learned from a review of the literature across five areas: access to high-quality professional learning opportunities, working conditions, compensation, decision-making authority, and accountability policies.

At the same time, our discussions with principals offered thoughtful solutions to address the challenges of the role:

- High-quality professional learning opportunities

- Support from strong administrative teams with adequate school-level resources

- Competitive salaries

- Appropriate decision-making authority within the school context

- Evaluations characterized by timely, formative feedback

These five remedies are grounded in the realities of schools and principals’ experiences, offering useful insights for district, state, and federal policy to reduce the turnover of effective principals.

We are grateful to the National Association of Secondary School Principals for its funding of this brief. Funding for this area of LPI’s work is also provided by the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, the Stuart Foundation, and the Sandler Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, and the Ford Foundation.