Elementary School Principals’ Professional Learning: Current Status and Future Needs

Summary

High-quality professional learning can build principals’ capacity to lead successful schools. This brief summarizes a study about principals’ professional learning based on a national survey of elementary school principals. Many surveyed principals reported that they had access to professional development that has been identified as important for leadership, but fewer had opportunities to participate in job-embedded professional learning, which research shows helps principals apply their learning. Most principals wanted more professional development, particularly on educating the whole child and on leading equitable schools. While a high percentage of principals said their districts supported their continuous improvement, many reported facing obstacles to participating in professional learning such as not having enough time, lacking sufficient coverage for leaving their building, and not having enough money.

The report on which this brief is based is available here.

School principals are essential for ensuring that students have access to strong educational opportunities. They shape a vision of academic success for all students; create a climate hospitable to education; cultivate leadership in others so that teachers and other adults feel empowered to realize their schools’ visions; guide instructional decisions that improve teaching and learning; and manage people, data, and processes to foster school improvement.National Association of Elementary School Principals. (2019). Leading Learning Communities: Pillars, Practices, and Priorities for Effective Principals. Alexandria, VA: Author; Fuller, E. J., Young, M. D., Richardson, S., Pendola, A., & Winn, K. M. (2018). The pre-K–8 school leaders in 2018: A 10-year study. Alexandria, VA: National Association of Elementary School Principals; The Wallace Foundation. (2013). The school principal as leader: Guiding schools to better teaching and learning. The Wallace Perspective: Expanded Edition. New York, NY: Author; Leithwood, K., & Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 17(2), 201–227; Leithwood, K. A., & Riehl, C. (2003). What we know about successful school leadership. Philadelphia, PA: Laboratory for Student Success, Temple University; Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A., & Lindsay, C. A. (2020). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. (Forthcoming).

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and its revelation of stark inequities in educational opportunity, the role of the principal has become even more critical in meeting students’ needs. Principals’ many responsibilities are consequential, affecting teacher retention,Hughes, A. L., Matt, J. J., & O’Reilly, F. L. (2015). Principal support is imperative to the retention of teachers in hard-to-staff schools. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 3(1), 129–134; Grissom, J. A. (2011). Can good principals keep teachers in disadvantaged schools? Linking principal effectiveness to teacher satisfaction and turnover in hard-to-staff environments. Teachers College Record, 113(11), 2552–2585; Grissom, J. A., & Bartanen, B. (2019). Principal effectiveness and principal turnover. Education Finance and Policy, 1–63; Burkhauser, S. (2017). How much do school principals matter when it comes to teacher working conditions? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(1), 126–145. school culture and climate,Hollingworth, L., Olsen, D., Asikin-Garmager, A., & Winn, K. M. (2018). Initiating conversations and opening doors: How principals establish a positive building culture to sustain school improvement efforts. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(6), 1014–1034. students’ social and emotional learning,DePaoli, J. L., Atwell, M. J., & Bridgeland, J. M. (2017). Ready to lead: A national principal survey on how social and emotional learning can prepare children and transform schools [CASEL Report]. Washington, DC: Civic Enterprises. and, ultimately, student achievement.Liebowitz, D. D., & Porter, L. (2019). The effect of principal behaviors on student, teacher, and school outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 785–827; Grissom, J. A., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2015). Using student test scores to measure principal performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 3–28; Dhuey, E., & Smith, J. (2014). How important are school principals in the production of student achievement? Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(2), 634–663; Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2012). Estimating the effect of leaders on public sector productivity: The case of school principals [NBER Working Paper w17803]. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; Coelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109; Dhuey, E., & Smith, J. (2018). How school principals influence student learning. Empirical Economics, 54(2), 851–882; Bartanen, B. (2020). Principal quality and student attendance. Educational Researcher, 49(2), 101–113; Chiang, H., Lipscomb, S., & Gill, B. (2016). Is school value-added indicative of principal quality? Education Finance and Policy, 11(3), 283–309; Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A., & Lindsay, C. A. (2020). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. (Forthcoming).

Research has found that high-quality professional learning opportunities for principals—including preparation programs, induction supports for early-career principals,Mitgang, L. (2012). The making of the principal: Five lessons in leadership. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation. ongoing training, one-on-one support through coaching and mentoring, and peer networksJacob, R., Goddard, R., Kim, M., Miller, R., & Goddard, Y. (2015). Exploring the causal impact of the McREL Balanced Leadership Program on leadership, principal efficacy, instructional climate, educator turnover, and student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(3), 314–332; Tekleselassie, A. A., & Villarreal, P. (2011). Career mobility and departure intentions among school principals in the United States: Incentives and disincentives. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 10(3), 251–293.—can build leadership capacity. Such learning opportunities can develop principals’ competence in leading across their full range of responsibilities, empowering them to foster school environments in which adults and students thrive. Principals who have access to high-quality professional learning are typically more likely to remain in the profession.Jacob, R., Goddard, R., Kim, M., Miller, R., & Goddard, Y. (2015). Exploring the causal impact of the McREL balanced leadership program on leadership, principal efficacy, instructional climate, educator turnover, and student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(3), 314–332; Miller, R. J., Goddard, R. D., Kim, M., Jacob, R., Goddard, Y., & Schroeder, P. (2016). Can professional development improve school leadership? Results from a randomized control trial assessing the impact of McREL’s balanced leadership program on principals in rural Michigan schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(4), 531–566; Tekleselassie, A. A., & Villarreal, P. (2011). Career mobility and departure intentions among school principals in the United States: Incentives and disincentives. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 10(3), 251–293. Additionally, teachers appear more likely to remain in schools led by principals who participate in these types of professional learning programs.Herrmann, M., Clark, M., James-Burdumy, S., Tuttle, C., Kautz, T., Knechtel, V., Dotter, D., Wulsin, C. S., & Deke, J. (2019). The effects of a principal professional development program focused on instructional leadership (NCEE 2020-0002). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education; Jacob, R., Goddard, R., Kim, M., Miller, R., & Goddard, Y. (2015). Exploring the causal impact of the McREL balanced leadership program on leadership, principal efficacy, instructional climate, educator turnover, and student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(3), 314–332; Miller, R. J., Goddard, R. D., Kim, M., Jacob, R., Goddard, Y., & Schroeder, P. (2016). Can professional development improve school leadership? Results from a randomized control trial assessing the impact of McREL’s balanced leadership program on principals in rural Michigan schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(4), 531–566.

To learn more about principals’ opportunities for professional learning, the National Association of Elementary School Principals (NAESP) and the Learning Policy Institute (LPI) collaborated on a national principal study. LPI surveyed a random sample of 1,000 principals who were members of NAESP and who were selected to represent U.S. elementary school principals proportionately by state. Between November 2019 and March 2020, 407 principals responded, for a 41% response rate.

Our study adds to the literature on professional learning for principals. After providing an overview of this literature, this brief presents our survey findings about elementary school principals and professional learning. It then concludes with implications for policy and practice based on the survey findings.

High-Quality Professional Learning for Principals

Research studies show that strong principals play an important role in creating a positive school culture,Hollingworth, L., Olsen, D., Asikin-Garmager, A., & Winn, K. M. (2018). Initiating conversations and opening doors: How principals establish a positive building culture to sustain school improvement efforts. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(6), 1014–1034. retaining good teachers,Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. and ensuring that students’ social and psychological needs are met.Adams, C. M., Olsen, J. J., & Ware, J. K. (2017). The school principal and student learning capacity. Educational Administration Quarterly, 53(4), 556–584. Furthermore, higher principal quality is associated with better graduation ratesCoelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109. and student achievement.Grissom, J. A., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2015). Using student test scores to measure principal performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 3–28; Dhuey, E., & Smith, J. (2014). How important are school principals in the production of student achievement? Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(2), 634–663; Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2012). Estimating the effect of leaders on public sector productivity: The case of school principals [NBER Working Paper w17803]. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; Coelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109.

Developing and supporting excellent principals requires strong preparation and ongoing high-quality professional development.Darling-Hammond, L., Wilhoit, G., & Pittenger, L. (2014). Accountability for college and career readiness: Developing a new paradigm. Stanford, CA: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. Yet many states and school districts have neglected the professional development of principals.Manna, P. (2015). Developing excellent school principals to advance teaching and learning: Considerations for state policy. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation; Rowland, C. (2017). Principal professional development: New opportunities for a renewed state focus. Washington, DC: Education Policy Center at American Institutes for Research. This neglect is discouraging given that many studies find that effective principals have a positive influence on schools, teachers, and students.Leithwood, K., Louis, K. S., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning: Review of research. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation; Grissom, J. A., Kalogrides, D., & Loeb, S. (2015). Using student test scores to measure principal performance. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 37(1), 3–28; Dhuey, E., & Smith, J. (2014). How important are school principals in the production of student achievement? Canadian Journal of Economics, 47(2), 634–663; Branch, G. F., Hanushek, E. A., & Rivkin, S. G. (2012). Estimating the effect of leaders on public sector productivity: The case of school principals [NBER Working Paper w17803]. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; Coelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109. High-quality, sustained principal professional learning opportunities offer a means of addressing the reality that schools serving many students from low-income families and students of color are often led by principals with less experience and less education who would most benefit from high-quality professional learning opportunities.Loeb, S., Kalogrides, D., & Horng, E. L. (2010). Principal preferences and the uneven distribution of principals across schools. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 32(2), 205–229; Quin, J., Deris, A., Bischoff, G., & Johnson, J. T. (2015). Comparison of transformational leadership practices: Implications for school districts and principal preparation programs. Journal of Leadership Education, 14(3), 71–85.

The literature on the impact of professional learning for principals is minimal, especially compared with similar literature on teachers. However, a recent review of the research literature demonstrates that participation in high-quality professional learning is associated with positive outcomes for principals.Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M., Levin, S., Campoli, A., Podolsky, A., Leung, M., & Tozer, S. (2021). Principal learning opportunities. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. (Forthcoming).

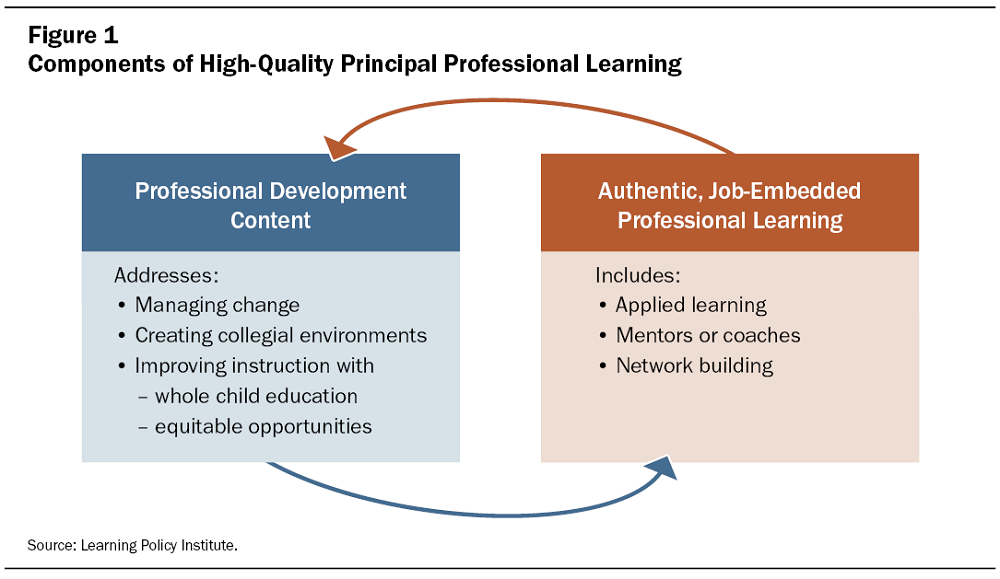

In 2017, LPI researchers conducted a review of the literature to identify the elements of high-quality, professional learning experiences related to improved school outcomes, such as improved student learning, increased principal and teacher effectiveness and retention, and improved perceptions of school climate.Sutcher, L., Podolsky, A., & Espinoza, D. (2017). Supporting principals’ learning: Key features of effective programs. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. They found that effective, high-quality principal development has the following attributes:

- content covering topics that address managing change, creating collegial teaching and learning environments, and improving instruction; and

- authentic, job-embedded professional learning opportunities, including applied learning experiences, individualized support from mentors or coaches, and networking structures such as professional learning communities (PLCs).Sutcher, L., Podolsky, A., & Espinoza, D. (2017). Supporting principals’ learning: Key features of effective programs. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M., Meyerson, D., Orr, M. T., & Cohen, C. (2007). Preparing school leaders for a changing world: Lessons from exemplary leadership development programs. Stanford, CA: Stanford University, Stanford Educational Leadership Institute; Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M., Levin, S., Campoli, A., Podolsky, A., Leung, M., & Tozer, S. (2021). Principal learning opportunities. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. (Forthcoming).

Additional research points to the need for learning opportunities in instructional improvement that take a whole child approach to teaching and learningDarling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Slade, S., & Griffith, D. (2013). A whole child approach to student success. KEDI Journal of Educational Policy, 10(3), 21–35 and ensure equitable outcomes for students.Ross, J. A., & Berger, M. J. (2009). Equity and leadership: Research-based strategies for school leaders. School Leadership and Management, 29(5), 463–476; Cosner, S., Tozer, S., Zavitkovsky, P., & Whalen, S. P. (2015). Cultivating exemplary school leadership preparation at a research intensive university. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 10(1), 11–38. Figure 1 summarizes these components of professional learning that research identifies as contributing to principal learning. Local policymakers and district leaders can play important roles in ensuring that principals have these types of professional learning opportunities to build their leadership capacities.Scott, C., Darling-Hammond, L., & Burns, D. (2020). Instructionally engaged leaders in positive outlier districts. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

NAESP-LPI Study Findings

This brief presents findings from a national survey of elementary school principals on their professional learning experiences over the past 2 years and the professional development they had been exposed to on the job.While the sample of 1,000 NAESP members was drawn to represent elementary school principals nationally, actual survey respondents were 89% elementary principals, 8% middle school principals, and 3% principals of schools with other grade configurations. We explore five overarching topics:

- Professional development content to support leadership capacity

- Authentic, job-embedded professional learning

- Professional development wanted by principals

- Obstacles to professional learning opportunities

- District support of principals’ professional learning

Professional Development Content to Support Leadership Capacity

Most elementary school principals had access to professional development content identified as important for building leadership capacity, including topics in leading equitable schools. Over 80% of principals had the opportunity to participate in professional development content focused on managing change, creating collegial teaching and learning environments, and improving schoolwide instruction. In fact, the topic that almost all principals said they had access to was using student or school data for continuous school improvement (98%). Additionally, many principals reported access to professional development about helping teachers improve through cycles of observation and feedback (95%). Principals also were likely to have participated in professional development in leading equitable schools, such as meeting the needs of students with disabilities (95%), equitably serving all children (91%), leading schools to support students from diverse backgrounds (88%), and meeting the needs of English learners (86%).

Authentic, Job-Embedded Professional Learning

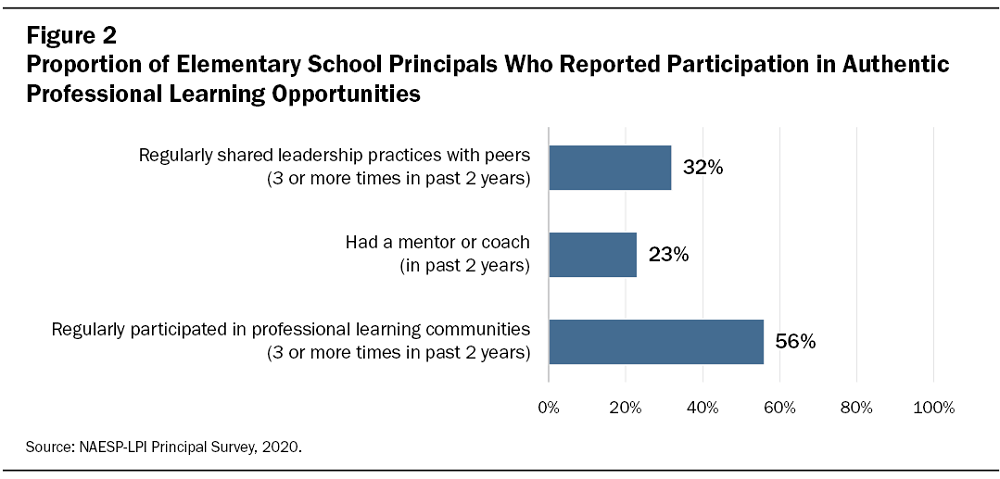

Many elementary school principals appear not to have had the opportunity to participate in authentic, job-embedded professional learning. Along with having access to professional development content that builds leadership capacity, principals benefit from having this content delivered through activities that are authentic and job embedded.Darling-Hammond, L., LaPointe, M., Meyerson, D., Orr, M. T., & Cohen, C. (2007). Preparing school leaders for a changing world: Lessons from exemplary leadership development programs. Stanford, CA: Stanford University, Stanford Educational Leadership Institute; Grissom, J. A., & Harrington, J. (2010). Investing in administrator efficacy: An examination of professional development as a tool for enhancing principal effectiveness. American Journal of Education, 116(4), 583–612. These activities include applied learning experiences (such as sharing leadership practices with peers), working with mentors and coaches, and participating in networking opportunities. Despite the research showing the importance of applied learning for effective professional development, our study finds that fewer than one third of all principals (32%) were able to spend time sharing leadership practices with their peers three or more times in the past 2 years (Figure 2).

Similarly, while the evidence points to the efficacy of mentors and coaches for principals, fewer than one quarter (23%) of principals responding to the survey reported having a mentor or coach in the past 2 years—and this percentage was lower for principals in high-poverty schools (10%). More principals had participated in PLCs—56% reported meeting with a PLC three or more times in the past 2 years—yet nearly half had not had this opportunity.

Professional Development Wanted by Principals

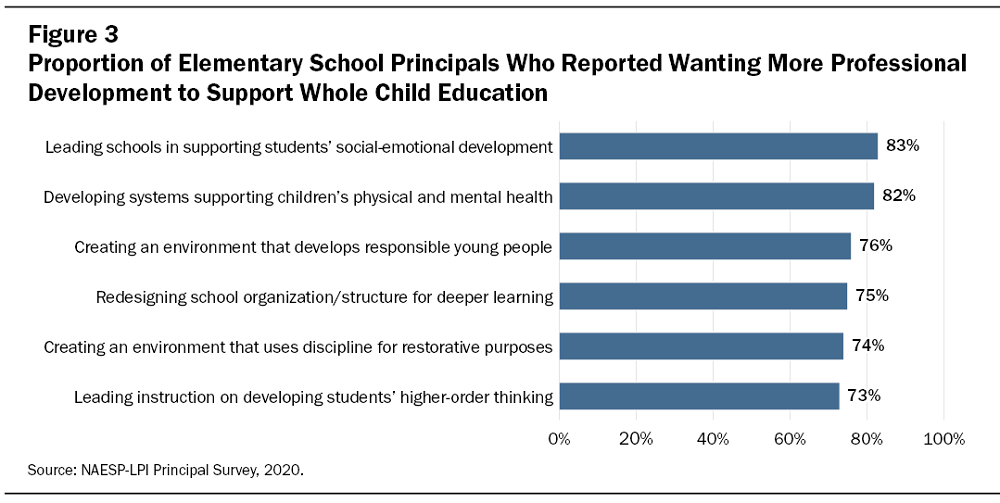

More than half of all elementary school principals wanted more professional development across all topics, but principals were most likely to want additional professional development that focuses on whole child education. Whole child education recognizes that all areas of a child’s development are connected. Therefore, whole child education includes challenging, in-depth learning opportunities, meeting students’ physical needs, and supporting their social and emotional learning.Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Specifically, principals reported their need for content on a range of supports for whole child education, from leading schools in supporting students’ social-emotional development (83%) to leading instruction on developing students’ higher-order thinking skills (73%). (See Figure 3.)

Many elementary school principals also indicated a need for professional development in leading equitable schools to ensure that all students have access to whole child education. This included meeting the needs of students with disabilities (71%), leading schools to support diverse learners (69%), equitably serving all students (69%), and meeting the needs of English learners (64%).

Obstacles to Professional Learning

More than four in five elementary school principals (84%) indicated that they faced obstacles to pursuing professional development. The top three reasons were not enough time (67%), insufficient coverage for leaving the building (43%), and not enough money (42%). Survey responses suggest that schools with larger proportions of historically underserved students are more likely to experience obstacles. Half of principals serving schools with high percentages of students of color reported lacking money for professional development (50%), compared with fewer than one third of principals of schools with low percentages of students of color (32%).We defined schools serving high percentages of students of color as those with 86% to 100% students of color. We defined schools serving low percentages of students of color as those with 0% to 20% students of color.

District Support for Professional Learning

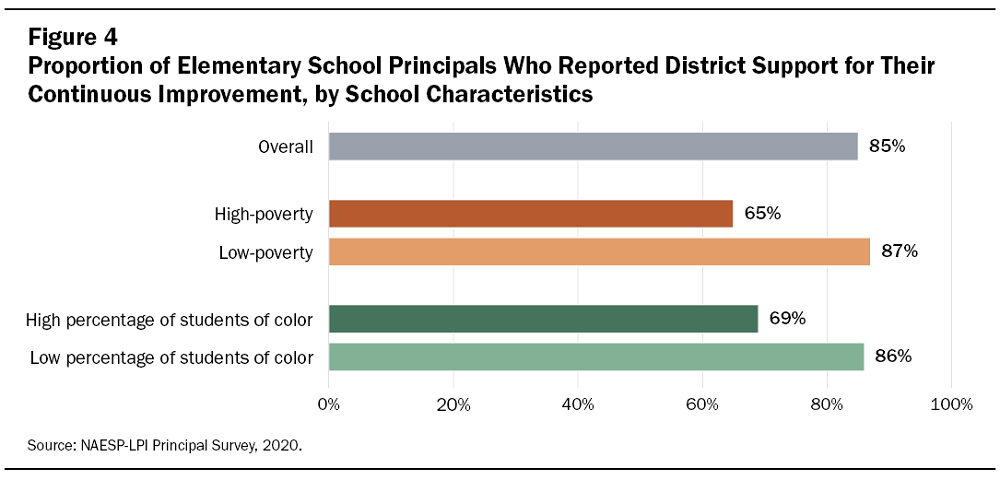

While a large majority of elementary school principals (85%) agreed that their districts supported their continuous improvement, there was considerable variation (Figure 4). Principals in high-poverty schools were less likely to report that their districts helped them overcome obstacles to professional learning: 65% in high-poverty schools compared with 87% in low-poverty schools.We defined high-poverty schools as those in which 80% to 100% of students were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. We defined low-poverty schools as those in which 0% to 28% of students were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch. Similarly, 69% of principals in schools with higher percentages of students of color reported that their districts helped them overcome obstacles, while 86% in schools with lower percentages of students of color indicated that they had this support from their districts.

Implications for Policy and Practice

High-quality professional learning can equip principals with the knowledge, mindset, and skills to support effective teaching and to lead across their full range of responsibilities. With this investment, principals are best positioned to foster school environments in which adults and students thrive. Policymakers should support principals by ensuring that they have access to high-quality professional learning opportunities. This support may be particularly useful during challenging times, such as during the pandemic that started in the spring of 2020 that moved both schooling and professional learning online or into hybrid forms.

At the Local Level

Policymakers at the local level have several options for supporting principals’ professional development:

Local policymakers can ensure that professional learning for principals embodies key features that help produce principals who can improve school outcomes. These features relate to the content of the professional development, as well as the delivery of content in authentic and job-embedded formats:

- Professional development focused on improving schoolwide instruction for whole child education. Relevant content, according to the principals surveyed, includes supporting students’ social-emotional development and physical and mental health, as well as creating school environments that develop responsible young people and foster critical thinking. Such content could be particularly valuable to school leaders as they support their communities due to the trauma and other challenges related to the COVID-19 crisis.

- Professional development focused on fostering equitable school environments. More than two thirds of principals expressed a need for professional development content in leading schools to support diverse learners and in equitably serving all students. This content aims to develop principals’ capacities to create a supportive, unbiased school environment that affirms each child as an individual; builds on students’ cultural assets through culturally responsive teaching; and fosters strong, trusting relationships among students and between students and adults.

- Meaningful applied learning experiences that are problem-based and context-specific. Only one third of surveyed principals reported having regularly shared leadership practices with peers in the past 2 years, an applied learning experience that reinforces principal learning. Problem-based, context-specific learning opportunities, such as school walk-throughs with peers or analyzing student data to identify problems, can enrich principals’ skill development.

- Mentors and/or coaches who provide principals with individualized support tailored to their needs. Only one quarter of surveyed principals reported having had a mentor or coach. However, for principals with all levels of experience, mentoring or on-the-job coaching can support them to foster school improvement and adopt new leadership methods.

- Opportunities to participate in collaborative learning, such as networks of practicing principals. Approximately half of surveyed principals reported participating in a PLC in the past 2 years. Effective learning utilizes PLCs or other network structures to enable school principals to collaborate in small groups of peers in order to learn on the job together. This allows principals to reflect continuously on their learning, individually and collectively.

Local policymakers can remove barriers to principal professional development. Many principals reported obstacles to participating in professional development, including lack of time, insufficient coverage for leaving the building, and lack of funds. District leaders can consider remedies such as providing district staff support that frees principals’ time and offering professional development at more convenient times and locations. As many schools continue to operate in remote and hybrid learning models, districts have a unique opportunity to plan and execute high-quality virtual principal professional development. Districts and schools can use both local and federal funds under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) Title II, Part A to provide funds for professional development.

At the State and Federal Levels

To support these local efforts, state and federal policymakers also have several options.

Federal policymakers can support local efforts to develop effective school leaders by increasing federal and state investments in high-quality professional learning. This could include increasing funding under ESSA Title I, Part A for school improvement and Title II, Part A for professional development. The federal government could also provide funding for the School Leader Recruitment and Support Program authorized under ESSA Title II, Part B. This program provides grants to states, districts, and universities for initiatives—including mentoring and coaching—to recruit, train, and support prospective and current principals in high-need schools. This program has not been funded since 2017.

Within each of these programs, the federal government could prioritize funds for engaging principals with curriculum focused on improving schoolwide instruction for whole child education and fostering equitable school environments. The federal government could also provide explicit support for collaborative learning, meaningful applied learning experiences that are problem based and context specific, and individualized support from coaches and mentors that is tailored to the needs of new and existing principals.

Support for principal professional learning could be increased in the future. For example, ESSA is due for reauthorization following the 2020–21 school year, and its funding to support school principals could be expanded. Increasing overall authorized funding levels and the set-aside for principals under this title would allow more principals to receive the high-quality professional development they need to be effective.

States can use federal funds to offset the expense of principals’ professional learning, whether in person or online. ESSA offers multiple opportunities to invest in high-quality school leadership, especially in high-need schools and communities. For example,

- States may allocate up to 5% of their state set-asides for statewide activities under ESSA Title II, Part A for teacher and leader development and an additional 3% exclusively for leadership investments. These investments can fund high-quality professional learning with content on managing change, creating collegial teaching and learning environments, and improving instruction, delivered through authentic, job-embedded professional learning opportunities. For example, these funds could be used to support mentoring, which is an induction requirement in some states, including Arkansas, Maryland, and Texas.Goldrick, L. (2016). Support from the start: A 50-state review of policies on new educator induction and mentoring. Santa Cruz, CA: New Teacher Center. States can use funds to provide training and facilitate networking opportunities for coaches and mentors to support each other. This could be especially valuable in states where mentoring is a requirement that has not yet translated into quality supports for principals.

- States can also allocate ESSA Title I, Part A school improvement funds, designated to improve low-performing schools by using evidence-based strategies, to implement research-based interventions that strengthen school leadership. Strengthening school leadership would require developing programs that invest in principals’ learning and create supports that attract and keep high-performing principals in high-need schools. A number of states proposed to do this as part of their plans under ESSA.Espinoza, D., Saunders, R., Kini, T., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2018). Taking the long view: State efforts to solve teacher shortages by strengthening the profession. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

- North Dakota, for example, proposed creating a leadership academy to provide professional support, professional development, career ladder opportunities, assistance with administrator shortages, and support to address administrator retention, as well as a resource to build leadership capacity in schools designated as in need of improvement pursuant to ESSA.North Dakota Department of Public Instruction. (2018, April 30). North Dakota Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) state plan. Bismarck, ND: Author, p. 96 A number of state ESSA plans incorporated equity-oriented initiatives to address leadership needs in schools and districts serving the students furthest from opportunity. For example, Colorado’s plan invests in leadership for high-poverty and high-minority schools; Vermont’s invests in training for principals to advance equitable access to great teachers in schools identified to be in need of improvement; Connecticut’s and Oklahoma’s plans prioritize training for turnaround school leaders; and Minnesota’s plan provides targeted professional development to principals of and their supervisors in schools identified to be in need of improvement.Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M., Levin, S., Campoli, A., Leung, M., & Tozer, S. (2021). Developing principals: What we know, why it matters, and what can be done. Principal learning opportunities. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. (Forthcoming).

States can use their own funds to support principal professional learning. A number of states, including Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Georgia, and North Carolina, have made significant investments in leadership academies and other initiatives to support principals throughout their careers.Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M., Levin, S., Campoli, A., Leung, M., & Tozer, S. (2021). Developing principals: What we know, why it matters, and what can be done. Principal learning opportunities. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. (Forthcoming). Others focus on the beginning of the career. For example, the Pennsylvania Inspired Leadership (PIL) Program is required of all new principals within their first 5 years of practice. The PIL induction program requires participants to complete formal coursework designed to provide principals with the strategic planning tools to implement high-quality teaching and train principals to use school data to identify school, teacher, and individual student needs.Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M., Levin, S., Campoli, A., Leung, M., & Tozer, S. (2021). Developing principals: What we know, why it matters, and what can be done. Principal learning opportunities. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. (Forthcoming).

At the School Level

To help ensure that they have access to useful professional learning opportunities, principals can advocate for district, state, and federal policymakers to support and fund:

- professional development content that meets principals’ needs, including improving schoolwide instruction for whole child education and fostering equitable school environments; and

- delivery of this content through authentic, job-embedded professional learning opportunities, such as applied learning experiences, mentoring and coaching, and PLCs.

Conclusion

High-quality professional learning—with content focused on principals’ learning needs and authentic, job-embedded professional learning opportunities—is key for building principals’ leadership capacities. While our study found that most elementary school principals responding to our survey had access to relevant professional development content, very few appeared to have had access to authentic, job-embedded professional learning. Also, many principals faced obstacles in pursuing professional learning. Further, principals from high-poverty schools were less likely than principals from low-poverty schools to report having an on-the-job mentor or coach, having funding for their professional development, or feeling supported in their learning by their school districts. Our study also found that elementary school principals were most likely to want additional professional development addressing whole child education. Many principals were also interested in professional development in leading equitable schools.

In light of our findings, federal, state, and district leaders and policymakers could implement a number of strategies to improve principals’ access to high-quality professional learning opportunities. These efforts to make high-quality, targeted professional development readily accessible can support principals in retaining teachers, raising student outcomes, and creating inclusive, equitable communities that tend to the social-emotional health of all students.

Elementary School Principals’ Professional Learning: Current Status and Future Needs (research brief) by Stephanie Levin, Melanie Leung, Adam K. Edgerton, and Caitlin Scott is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported, in part, by the Wallace Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. We are grateful to them for their generous support.