Developing Effective Principals: How Policies Can Make a Difference

Summary

Research has found that high-quality preparation and professional development improve principals’ effectiveness and are associated with increased teacher retention and student achievement in the schools those principals serve. However, not all principals have sufficient access to high-quality learning, and differences across states reflect varied state policies. This brief examines how state and district policies influence principals’ access to high-quality learning opportunities during preparation and throughout their careers. It identifies a set of policy levers that states and districts can adopt to promote principal effectiveness. These include standards for leadership practices, preparation programs, and licensure and investments in induction programs, leadership pipeline programs, and professional development.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

How Access to High-Quality Learning Matters

High-quality leadership training matters for principals, their teachers, and their students. A growing body of research shows that principals have significant effects on a wide range of school outcomes—from school climate and student achievement to teacher practices and retention.Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. The Wallace Foundation. Furthermore, high-quality learning opportunities are associated with principals’ beliefs and practices, their sense of efficacy, teacher satisfaction and retention, school climate, and student achievement and attainment.Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M. E., Levin, S., Leung-Gagné, M., & Tozer, S. (2022). Developing effective principals: What kind of learning matters? [Report]. Learning Policy Institute. A study of California principals that was able to control for a wide range of other student, teacher, and school characteristics found that strong principal preparation and access to professional development were significantly associated with increased teacher retention and student achievement.Campoli, A. K., & Darling-Hammond, L. (with Podolsky, A., & Levin, S.). (2022). Principal learning opportunities and school outcomes: Evidence from California. Learning Policy Institute. In that study and others, the features of effective principal learning opportunities include:

- content focused on key levers of principals’ practices, such as leading instruction, developing people, supporting a collegial organization, and managing change;

- authentic and applied learning opportunities, including field-based internships and problem-based approaches such as case studies and action research projects; and

- expert support, such as coaching and mentoring, along with networks of peers who share and solve problems of practice together.

Learning opportunities and professional support are important throughout a principal’s career, including during preservice preparation, induction into the profession, and ongoing service through retirement. Principals’ access to high-quality training has improved since 2000, although there is still a long way to go before all principals have ready access to consistent, high-quality learning opportunities. Most principals report that they have received preservice or in-service training on content related to key areas of practice—and evidence shows that such access has increased over time—but the quality of their learning opportunities has not evolved nearly as quickly.

Only about half of principals across the country were trained in a preparation program that was problem-based, field-based, or cohort-based or that included a strong internship featuring mentoring or coaching from an experienced principal—features that distinguish effective programs from less effective ones. In addition, national survey data show that the content and learning opportunities principals can access vary across states and between high- and low-poverty schools, reflecting differences in state policies.

Because principal effectiveness strongly affects school functioning and influences a broad set of school, teacher, and student outcomes, states and districts have a vested interest in ensuring that principals have access to high-quality learning experiences. Through an extensive literature review and policy scan, our study of principal learning identified a set of policies that states and districts have used to transform and strengthen principal development. These include standards for leadership practices, preparation programs, and licensure; induction policies; leadership pipeline programs; and investment in professional development.

Standards for Leadership Practices, Preparation Programs, and Licensure

Among the key policy levers controlled by state agencies are the standards for leadership practices, preparation programs, and licensure that are used to set expectations for performance, evaluation, and training. These standards can be used to create greater coherence among the many policies and initiatives that influence learning and practices when they are used comprehensively throughout the principal development system and translated into tools such as performance assessments. When used in this way, standards form the basis for systemic change.

Over the past few decades, standards for principals have become increasingly research-based; have included greater focus on how to support student learning and staff development, rather than management of buildings and programs; and have been translated into systems of evaluation.

The first set of leadership standards, the Interstate School Leaders Licensure Consortium standards, was published in 1996 by the Council of Chief State School Officers and revised in 2008 to incorporate greater emphasis on student learning. By 2014, all 50 states plus Washington, DC, had adopted or adapted the revised standards. In 2015, the Professional Standards for Educational Leaders—which had an even stronger focus on equity—were developed by national professional associations of principals and administrators through the National Policy Board for Educational Administration. As state licensure standards have evolved over the past 25 years, they have increasingly included a focus on the knowledge and skills associated with supporting student learning. As a result, across the country, many preparation programs have evolved to emphasize content on leading instruction, developing staff, focusing on equity, and providing more authentic clinical experiences.

Some states have leveraged leadership standards to inform principal preparation program approval standards, sunsetting old principal leadership programs when new, higher standards are introduced and allowing only those programs that meet the standards to admit students. However, fewer states require the high-leverage policies identified in a 2015 study by the University Council for Educational Administration,Anderson, E., & Reynolds, A. (2015). The state of state policies for principal preparation program approval and candidate licensure. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 10(3), 193–221. such as implementing a proactive selection process to recruit dynamic educators who demonstrate instructional leadership, offering a clinically rich internship under the wing of an expert principal for a substantial period of time, requiring district–university partnerships, setting education and experience requirements for a license, or ensuring well-designed program oversight with regular feedback. As of 2015, fewer than half the states required that programs include a rigorous selection process, a clinically rich internship, district–university partnerships, an advanced degree in educational leadership, or performance-based assessment for licensure.

Illinois is one of two states (along with Tennessee) that implemented all the high-leverage criteria described in the University Council for Educational Administration’s study. Illinois’s experience with updating its program approval standards (see “Illinois’s Reform of Principal Preparation Programs”) demonstrates the impact that program approval standards can have across all aspects of program design, including enrollment, curriculum, focus on diverse student populations, internship requirements, and continuous improvement processes.

Illinois’s Reform of Principal Preparation Programs

In the 1990s, Chicago Public Schools began a 25-year investment in school principal improvement policies, including by forming partnerships with select university programs, such as those at the University of Illinois Chicago (UIC) and Northeastern Illinois University. UIC, for example, began a 2-year process in 2000 to fully reimagine its preparation experience, striving to prepare principals more effectively with the knowledge and skills they would need to lead improvement in Chicago Public Schools. UIC turned its yearlong master’s program into a multiyear doctoral program that is selective, cohort-based, and clinically intensive. During this time of significant investment in principal preparation and development, Chicago Public Schools steadily and dramatically improved its student performance measures, and UIC demonstrated that its graduates significantly improved student outcomes relative to students in other, similar schools in the city.

The state of Illinois set out to improve preparation program standards and quality as well. An Illinois Board of Higher Education commission—composed of leaders from schools, colleges and universities, business organizations, professional education organizations, the Illinois State Board of Education, and the Illinois Board of Higher Education—released a report about improving principal preparation through research-based strategies. The recommendations for program standards were influenced by the success of Chicago’s investments in principal development.

In 2010, the state legislature enacted the proposed changes to principal preparation program accreditation. The new program approval standards required that programs include formal partnerships between principal preparation programs and districts, a rigorous selection process, alignment with local and national standards, a performance-based internship, supervision of candidates, and an assessment leading to principal endorsement.

These changes to program design standards were substantial. Just a year after the final sunsetting of all principal preparation programs in Illinois that did not meet the new standards, an implementation study of the state’s new principal preparation policies documented changes in many areas, including:

- Enrollment: Enrollments in preparation programs dropped as programs moved from general administrative training to a principal-specific focus. Many fully online programs chose to discontinue. Stakeholders generally viewed this change as a shift from quantity to quality that benefited principal preparation.

- Partnerships: The redesign strengthened partnerships between programs and districts.

- Curriculum: Programs revamped curricula and internships to focus on instructional leadership, while strong attention to organizational management continued.

- Attention to diversity: Special education, early childhood, and English learner student populations received increased coverage in both coursework and internships.

- Mentoring and internships: The new internship requirements—including instructional leadership opportunities, more direct leadership, and experiences working with many types of students—were generally viewed as deeper, clearer, and more authentic.

- Continuous improvement: An increased focus on continuous improvement highlighted the importance of better data collection and analysis of candidate outcomes.

Sources: Reardon, S. F., & Hinze-Pifer, R. (2017). Test score growth among Chicago public school students, 2009–2014. Stanford Center for Education Policy Analysis; Zavitkovsky, P., & Tozer, S. (2017). Upstate/downstate: Changing patterns of achievement, demographics and school effectiveness in Illinois public schools under NCLB. Center for Urban Education Leadership; White, B. R., Pareja, A. S., Hart, H., Klostermann, B. K., Huynh, M. H., Frazier-Meyers, M., & Holt, J. K. (2016). Navigating the shift to intensive principal preparation in Illinois: An in-depth look at stakeholder perspectives [IERC 2016-2]. Illinois Education Research Council at Southern Illinois University.

California’s Use of Standards for Comprehensive Transformation

Another state that more recently revised its licensure and accreditation standards in a comprehensive fashion is California. In 2014, California adopted a new set of research-based leadership standards, the California Professional Standards for Education Leaders, and integrated them into licensure and accreditation processes. The standards emphasize educating diverse learners from a whole child perspective, integrating social and emotional learning and restorative practices, developing staff, and using data for school improvement. These leadership standards were translated into Administrator Performance Expectations that informed program approval standards, licensing, new expectations for both preservice training and induction, and later an administrator performance assessment, which was piloted for the first time in 2018–19.

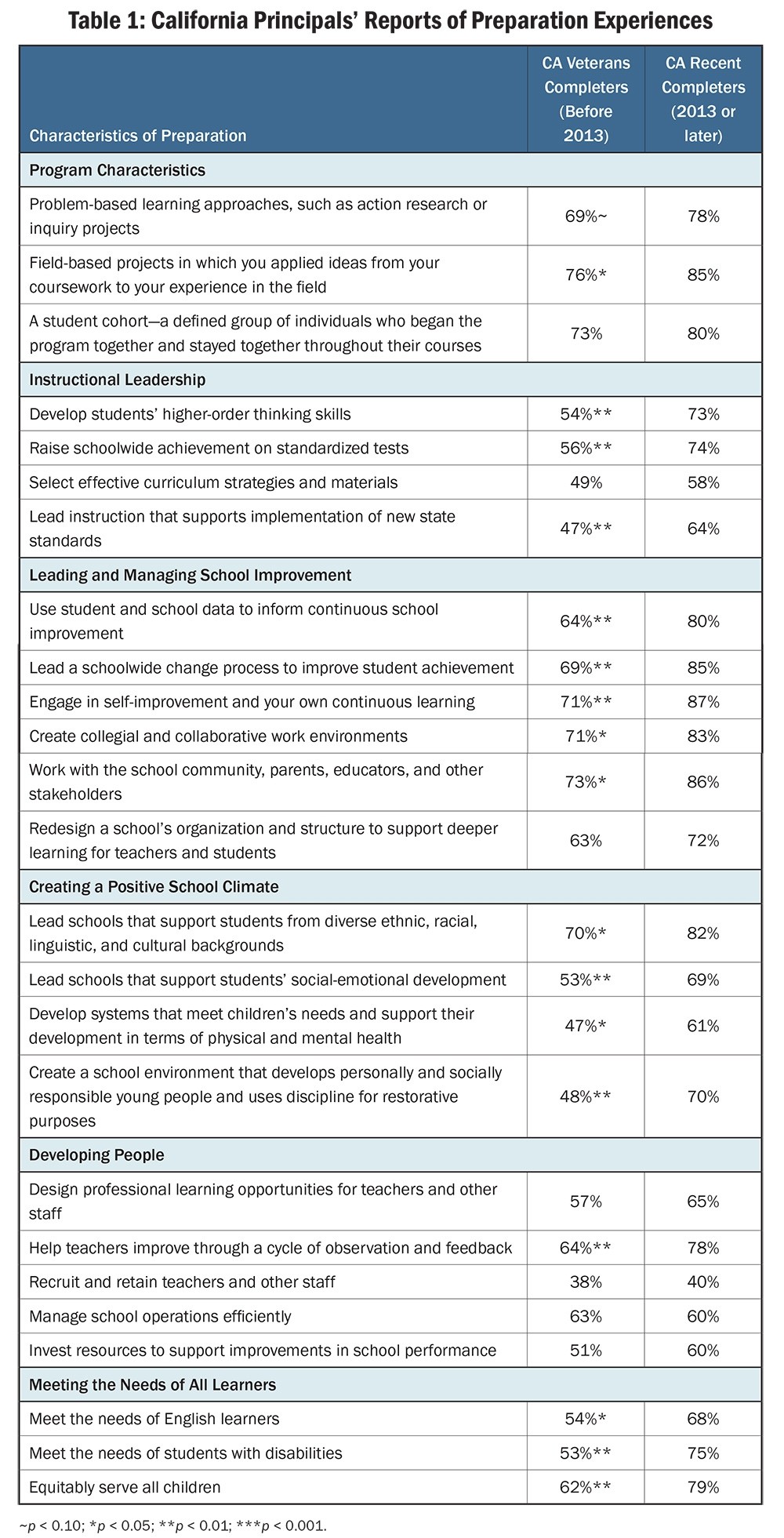

These changes in standards guiding both preservice and induction programs were associated with improvements in principals’ perceptions of their preparation. Data from a representative sample of more than 400 California principals show that more recently prepared principals felt significantly better prepared than did veteran principals in virtually all of the areas that were integrated into the new standards, with large changes related to instructional leadership; the ability to lead school improvement, especially for whole child approaches such as social and emotional learning and restorative practices; and the ability to meet the needs of diverse learners. (See Table 1.) Newly graduated principals were also more likely to have experienced problem-based learning approaches and field-based projects, which were part of the new program expectations, suggesting that the reforms did indeed affect program designs.

Moreover, the strength of California’s preparation programs was found, in turn, to be associated with principals’ effectiveness. For example, principals’ overall preparation quality and preparation in the areas of developing staff and meeting the needs of diverse learners (topics included in the new state licensure) were positively related to teacher retention and student achievement.Campoli, A. K., & Darling-Hammond, L. (with Podolsky, A., & Levin, S.). (2022). Principal learning opportunities and school outcomes: Evidence from California. Learning Policy Institute.

When states comprehensively strengthen and align standards for leadership, programs, and licensure, they can change the quality of principals’ preparation and effectiveness.

Source: California Principal Survey. (2017).

Induction Programs

After completing preservice preparation, principals benefit from additional support during an induction period for their new leadership roles. Induction may include coaching, coursework, and support from expert senior leaders and, when well implemented, has been associated with increased principal and teacher retention as well as increased student achievement.Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M. E., Levin, S., Leung-Gagné, M., & Tozer, S. (2022). Developing effective principals: What kind of learning matters? [Report]. Learning Policy Institute.

As of 2016, 20 states had introduced principal induction requirements, generally mandating that new principals complete induction during their initial years in the field. Seventeen states required mentoring for new principals, and 15 required coursework. Of these, three states—Hawaii, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina—require specific coursework. Pennsylvania’s induction program, for example, offers coursework focused on student learning and supportive teaching for equitable outcomes, along with mentoring. The program, which is offered through the National Institute for School Leadership, has been found to significantly increase the effectiveness of novice principals. (See “Pennsylvania’s Focused Approach to Induction.”)

Pennsylvania’s Focused Approach to Induction

All Pennsylvania principals must participate in the Pennsylvania Inspired Leadership Program during their first 5 years of employment. The program requires principals to take formal coursework tied to an action research project in which they take up a problem in their school, conduct research and apply evidence to understand the sources of the problem, and evaluate the results of a solution they have undertaken. The program focuses on competencies included in the state’s leadership standards. The coursework provides principals with training in how to examine school data to identify school, teacher, and individual student needs and use strategic planning tools to implement a plan for high-quality teaching and learning.

A study of this program over an 8-year period from 2008–09 to 2015–16 found that principals’ participation—especially during their first 2 years as a principal—was associated with improved student achievement and teacher effectiveness in mathematics, with the strongest relationships concentrated among the most economically and academically disadvantaged schools in Pennsylvania. In addition, teacher turnover in participants’ schools declined in the years following principals’ participation in the program.

Source: Steinberg, M. P., & Yang, H. (2021). Does principal professional development improve schooling outcomes? Evidence from Pennsylvania’s Inspired Leadership induction program [EdWorkingPaper 20-190]. Annenberg Institute at Brown University.

Leadership Pipeline Programs

Policies can also influence local districts’ abilities to recruit, prepare, induct, and develop principals. A number of districts have developed leadership pipeline programs that identify talented educators and support them from their entry into the profession through multiple leadership roles. State standards for leadership, program approval, and licensure serve as the foundation for these programs. Common strategies employed by leadership pipeline programs include:

- adopting standards of practice and performance that guide principal preparation, hiring, evaluation, and support;

- delivering high-quality preservice preparation to high-potential candidates—often dynamic teachers who have been instructional coaches or mentors—typically through a combination of in-district programs and partnerships with university programs;

- using selective hiring and placement, informed by data on candidates’ demonstrated skills, to match principal candidates to schools; and

- aligning on-the-job evaluation and support for novice principals with an expanded role for principal supervisors in instructional leadership.

The six urban school districts that adopted a principal pipeline strategy in 2011 as part of a Wallace Foundation initiative—Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools, NC; Denver Public Schools, CO; Gwinnett County Public Schools, GA; Hillsborough County Public Schools, FL; New York City Department of Education, NY; and Prince George’s County Public Schools, MD—provide evidence of the strategy’s effectiveness. Newly placed principals in the initiative were more likely than newly placed principals in comparison schools to remain in their schools for at least 3 years, and students in schools led by new principals who were part of the initiative outperformed those in comparison schools.Gates, S. M., Baird, M. D., Master, B. K., & Chavez-Herrerias, E. R. (2019). Principal pipelines: A feasible, affordable, and effective way for districts to improve schools. RAND Corporation.

Investment in Professional Development

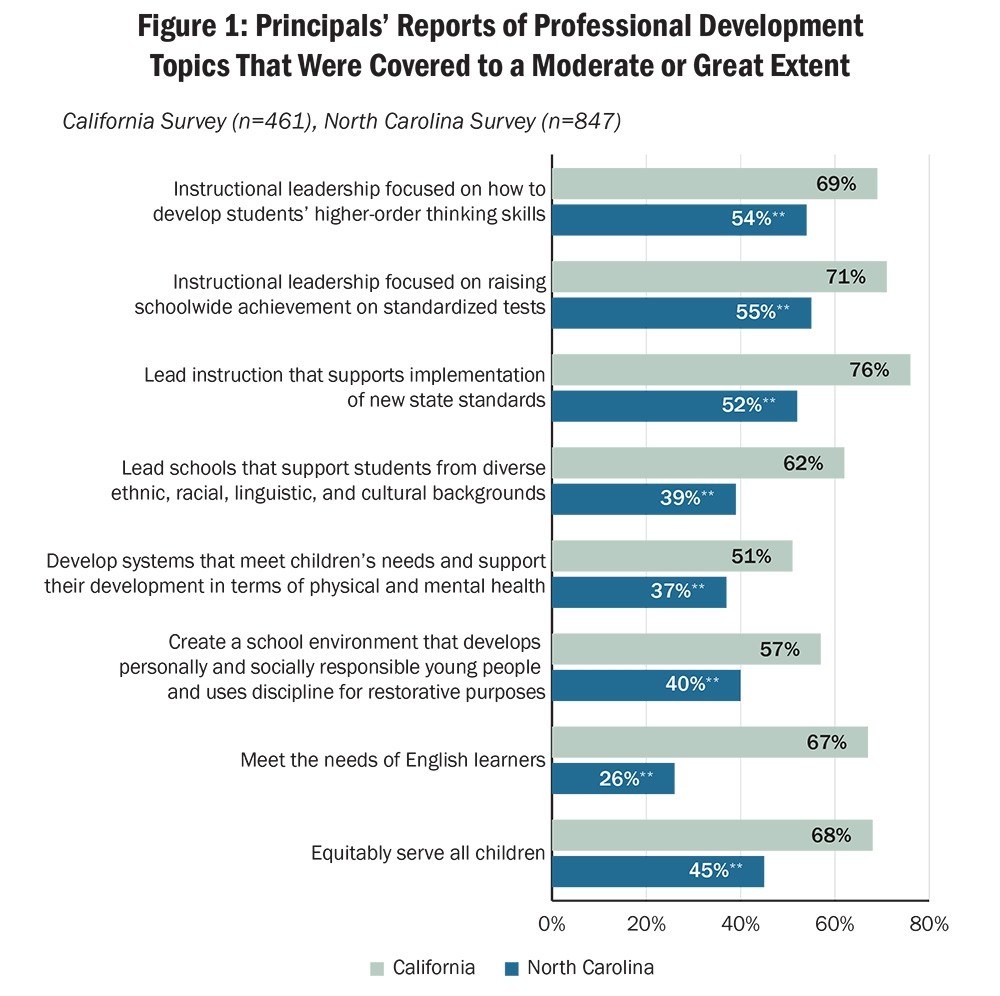

The level and nature of a state’s investment in professional development also influence principals’ access to learning opportunities, ranging from workshops and principal networks to coaching and mentoring. The impact of state-level investment can be seen in the examples of California and North Carolina, where principal surveys revealed large differences in access to and satisfaction with professional learning opportunities. Between 2014 and 2020, California implemented policy changes that allocated significant funding for professional development associated with the adoption of new student learning standards and related administrator and teacher expectations. At the same time, North Carolina instituted budget cuts, which impacted professional development funding, among other areas.

Compared with North Carolina principals, California principals reported that they experienced more in-depth opportunities to learn in nearly all professional development content categories, often by large margins, especially in the categories of instructional leadership, building a positive school environment (which is part of California’s school accountability system), and meeting the needs of diverse learners. (See Figure 1.) The differentials were largest around equity-oriented leadership skills, such as leading schools that support students from diverse ethnic, racial, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds (62% of California principals vs. 39% of North Carolina principals); serving all children equitably (68% vs. 45%); and meeting the needs of English learners (67% vs. 26%). Furthermore, whereas the distribution of professional development to principals of high- and low-poverty schools was inequitable nationally and in North Carolina, there were no differences in access in California, where principals from all kinds of schools had strong access to learning opportunities.

Policy Implications

Policymakers have a wide array of strategies to consider that can expand principals’ access to high-quality learning opportunities, and these policies appear to be most impactful when adopted together as a comprehensive approach to improving the quality of principal preparation and ongoing professional development. State and local policymakers can support the quality and quantity of preservice and in-service learning opportunities by taking several actions.

Develop and effectively use state licensing and program approval standards to support high-quality principal preparation and development.

All states and Washington, DC, have adopted standards to guide principal licensure, and many have developed new requirements for principals, such as having a valid educator license, having experience in an educational setting, completing a preparation program, and passing an assessment. Only a few states, however, have fully used the standards to guide performance-based approaches to licensing, intensive approaches to preparation program accreditation, or approval that could result in stronger program models. Likewise, only a few states have adopted high-leverage program approval policies, such as requiring clinically rich internships and university–district partnerships. Because policy shifts have not taken on the most critical strategies in the most powerful ways, considerable variability still exists in terms of principals’ opportunities for high-quality preservice learning across the country.

States’ stronger use of licensure and program approval standards can help ensure that principal training includes the features of high-quality programs and content focused on critical areas of principal practice (e.g., leading instruction, shaping a positive school culture, developing people, and meeting the needs of diverse learners). States can also use standards to emphasize the types of learning opportunities that matter for effectiveness, such as quality internships, applied learning, and coaching and mentoring under the auspices of an experienced principal.

Invest in a statewide infrastructure for principals’ professional learning.

State investment in professional learning that focuses on critical content and successful strategies can support principals’ effectiveness and make such learning available in a more equitable way. In addition to using their own funds, states can leverage federal funds provided by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) to support the development of school leaders. ESSA permits states to set aside 3% of their Title II formula funds to strengthen the quality of school leaders, including by investing in principal recruitment, preparation, induction, and development. Some states have used these funds to launch and sustain school leadership academies. States can also leverage other funds under Titles I and II of ESSA to invest in leadership training for schools that are identified as needing support and intervention, as well as to strengthen both teacher and school leadership skills for implementing a wide range of improvements in schools. These funds were dramatically expanded by the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 and can be used to prepare principals to support students’ social-emotional skills and learning needs.

Using ESSA funds and other investments, states are in a position to ensure principals have coordinated, high-quality, and sustained professional learning. For example, paid internships for leadership preparation can enable high-quality candidates to enter school leadership roles with a better developed skill set but without going into debt. Paid internships also make it feasible for candidates to take the necessary time for intensive clinical placements. Support for clinical partnerships between programs and districts can ensure that internships, along with mentoring opportunities for novice principals and coaching for veterans, become universal and sustainable.

Undertake comprehensive policy reforms at the local level to build a robust pipeline of qualified school principals and a coherent system of development.

Encourage districts, through competitive grants and technical assistance, to launch pipeline programs, which have proved to be effective for finding teachers with leadership potential and carrying them along a supportive pathway to becoming principals. Pipelines for qualified leadership candidates start before preparation with targeted recruitment. Deliberate recruitment can identify teachers who have already demonstrated leadership capacity and have the potential to contribute to positive school outcomes. Such recruitment also gives schools and districts the opportunity to pick candidates who will meet their local needs, are known to be dynamic teachers and instructional leaders, and represent historically underserved populations.

Following recruitment, pipelines incentivize and support ongoing learning for leaders that is organized around standards that bring a coherent vision to preparation and induction, as well as high-quality shared learning opportunities for veteran leaders. Pipelines help keep strong principals engaged and build local capacity. They not only improve the practice of individuals and create a supply of qualified leaders for school and district positions but also contribute to districtwide practices that support systemic change and increase student learning and equity.

In sum, policies that support evidence-based approaches to preparation and professional learning throughout principals’ careers and make these opportunities readily available to all school leaders can make a measurable difference in student, teacher, and school outcomes.

Developing Effective Principals: How Policies Can Make a Difference (brief) by Linda Darling-Hammond, Marjorie E. Wechsler, Stephanie Levin, Melanie Leung-Gagné, and Steve Tozer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Wallace Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced in this brief are those of the authors and not those of our funders.