Principal Learning Opportunities and School Outcomes: Evidence from California

Summary

Preparation and professional development can help principals be more effective leaders, but little research has examined what specific approaches are most useful. A study of 462 California principals and the teachers and students in their schools shows that high-quality preservice preparation for principals is associated with stronger teacher retention, and that overall access to professional development—as well as specific learning about instructional leadership—is strongly associated with student achievement gains in both mathematics and English language arts. Underrepresented students of color benefit the most from their principals’ opportunities to learn, as do the students of early-career professionals.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

The Importance of Principal Leadership and Learning

A growing body of research highlights the importance of principal leadership, suggesting that principals can have a substantial influence on school conditions and students’ learning. The emerging research also identifies behaviors that are associated with quality principal leadership. But how can principals learn to be good leaders? Are there professional learning strategies that make a difference in principal effectiveness?

We tackled these questions in a recent study of California principals. Using detailed surveys about professional learning experiences from a representative sample of 462 principals and linked administrative data from approximately 14,000 teachers and 314,000 students, the study linked various aspects of principals’ learning opportunities to teacher and student outcomes. Rarely examined in previous studies, these relationships offer new insights into principal learning and leadership and the influence they can have on teacher retention and academic gains for students. This brief describes the study and summarizes its key findings.

Principal Learning Matters

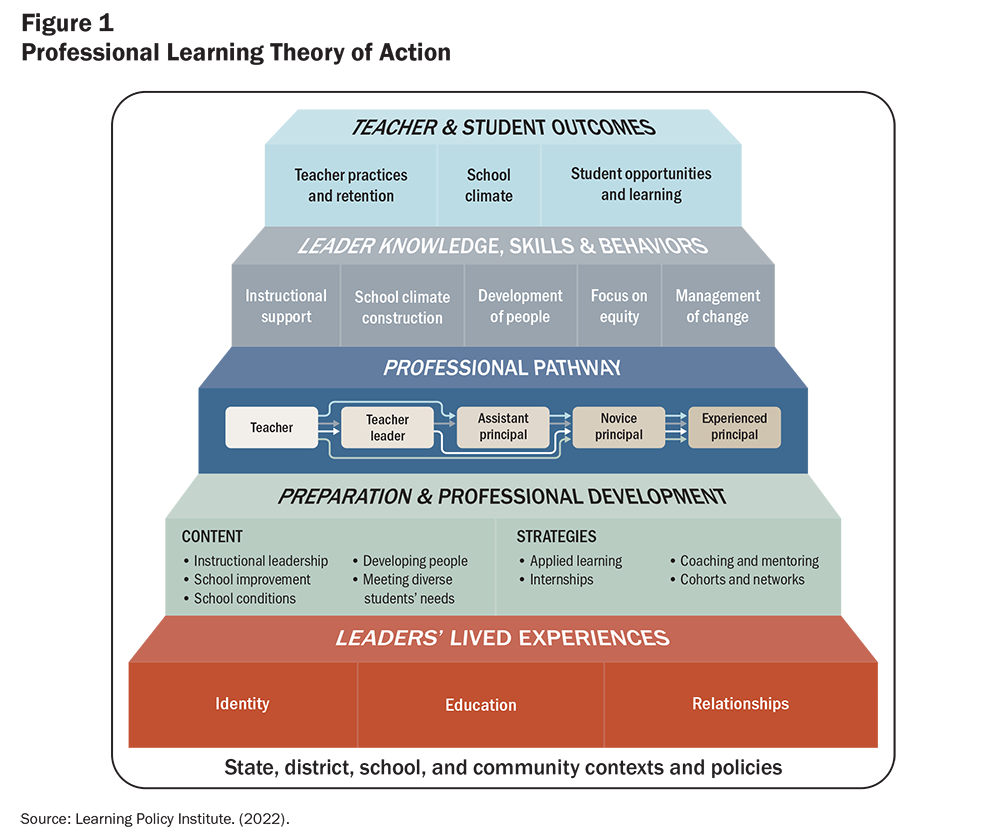

Overall, the results of the study are promising in showing how quality principal learning can be related to positive outcomes in schools. Quality learning opportunities for principals—both preservice and in-service—appear to enhance the likelihood that teachers will stay in their jobs and students will make gains in academic achievement. As outlined in a comprehensive review of the research, these quality learning opportunities include both the kinds of content that enable principals to respond to contemporary expectations of their role and methods of learning that are powerful for developing practice.Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M. E., Levin, S., Leung-Gagné, M., & Tozer, S. (2022). Developing effective principals: What kind of learning matters? [Report]. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/641.201 As shown in Figure 1, the content elements include learning how to lead instruction, improve school climate and conditions, develop staff, and meet diverse students’ needs in a way that attends to the whole child. Effective methods of learning allow candidates to apply knowledge in practice through case studies, real-world projects, and internships. Mentoring and coaching from expert veterans, and opportunities to be part of a cohort or network, are also important factors in the learning process.

Making Links

We explored two different stages in principals’ learning:

- Stage 1: Preservice, the preparation and learning that occurs before serving as principal

- Stage 2: In-service, the learning that takes place through professional development while serving as principal

We studied the overall quality of principal learning, as well as the key content elements of quality principal learning at both stages. These content elements and how they are related to principals’ experiences and practices are outlined in Figure 1.

Careful Design for Relevant Results

The sample of principals taking part in the study was selected to be representative of the state’s principals in terms of school level and types of districts in which they serve, so that the findings could be generalized to principals across the state. The study was also carefully designed to focus on the influence of principal learning. Many different factors—such as the characteristics of teachers, students, and schools—could potentially impact teacher and student outcomes, so we controlled for these factors in our statistical analyses, to isolate the relationships of principal learning to teacher retention and student achievement gains.

We also ensured that the impact of preservice learning could be more clearly identified by including only those principals with fewer than 6 years of experience in the study of preservice learning, when its effects were more likely to be felt and would be less confounded with learning from experience or other professional development. All principals were included in the study of professional development.

Principal Preservice Learning Fosters Teacher Retention

The study shows there is a strong connection between principals’ overall preparation quality and teacher retention, which is positive for all the elements of preservice preparation we examined. There was a significantly higher likelihood of teacher retention when principals were specifically prepared for the tasks of developing people and meeting the needs of diverse learners. This suggests that principals who had learned how to support teachers’ professional learning and practice may have created productive conditions that encouraged teachers to stay.

Other studies indicate that teachers are more likely to stay when they are in collegial contexts and when they feel efficacious in their work,Darling-Hammond, L., Chung, R., & Frelow, F. (2002). Variation in teacher preparation: How well do different pathways prepare teachers to teach? Journal of Teacher Education, 53(4), 286–302. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022487102053004002; Kraft, A. K., & Papay, J. P. (2014). Can professional environments in schools promote teacher development? Explaining heterogeneity in returns to teaching experience. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 36(4), 476–500. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373713519496 which occurs as teachers learn and plan together. It may be that a principal’s understanding of how to meet the needs of diverse learners also supports teacher efficacy as teachers are enabled to engage in practices that are successful and as their school offers the kinds of support services that help meet students’ needs.

The study also found that students whose principals had engaged in higher-quality internships during their preservice learning made greater gains in English language arts (ELA) than their peers whose principals’ internships had been of lower quality. This reinforces the importance and value of high-quality internships—those that offer candidates the opportunity to lead, facilitate, and make decisions typical of a practicing educational leader—for people preparing to become effective principals. The internship experience can also help the candidate understand school improvement from the perspective of a school leader, with support from a mentor. Other research finds that this kind of internship experience is one of the most important elements of high-quality preparation programs.Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M. E., Levin, S., Leung-Gagné, M., & Tozer, S. (2022). Developing effective principals: What kind of learning matters? [Report]. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/641.201

Principal In-Service Learning Fosters Student Learning

The study shows there is a strong connection between principals’ professional development opportunities and projected academic gains for students. More specifically, the research shows that principals’ overall in-service learning is associated with gains in both ELA and mathematics, with the influence in math being particularly pronounced.

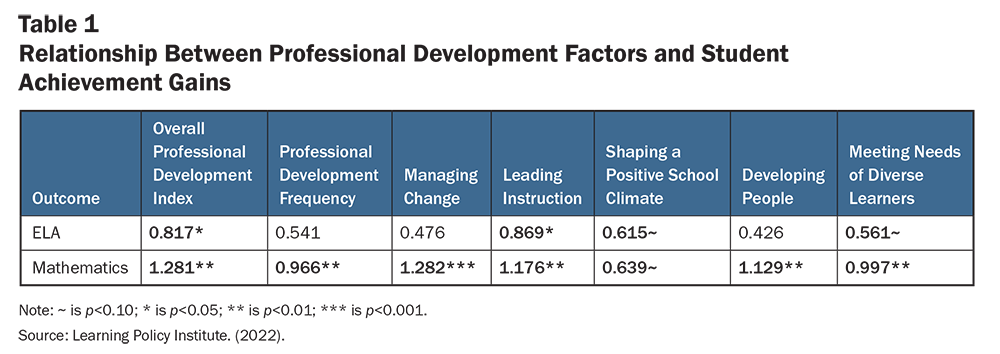

As Table 1 shows, all areas of professional development are positively related to student learning gains in ELA and math, and several reach levels of at least marginal statistical significance in both subjects, including instructional leadership, shaping a positive school climate, and meeting the needs of diverse learners. In addition, principals’ professional development experiences in managing change and developing people are strongly related to student learning gains in mathematics.

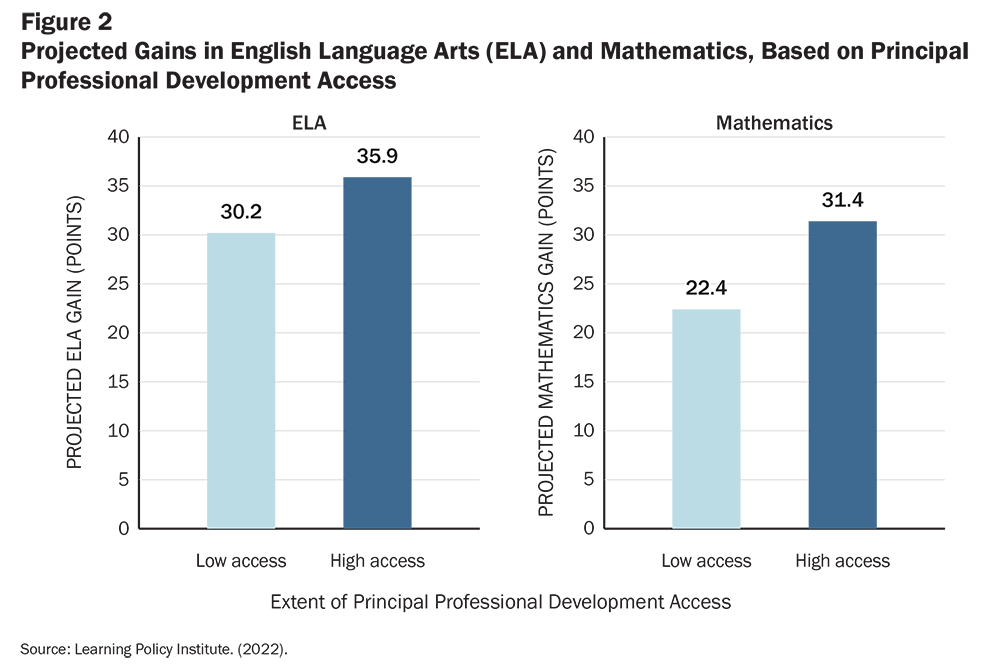

To illustrate the strength of these relationships, Figure 2 compares likely progress for two different students in ELA and in math. Imagine that both students started out with roughly the same level of academic achievement, near the norm, but the first student’s principal had little or no access to professional development, and the second student’s principal had high access to professional development (examining multiple key topics frequently). Based on this study, the average student whose principal had more access to professional development is projected to make greater gains in both ELA and math. In fact, these gains are equivalent to an additional 29 days of learning in ELA and 3 months’ worth of additional math instruction.

Learning About Instructional Leadership Offers Strong Leverage on Achievement

The research also highlights that achievement gains are strongly linked to specific aspects of principals’ professional development, with the influence being especially powerful for historically underserved students. For example, findings from the study suggest that principals’ access to professional development in instructional leadership is significantly related to student achievement gains in both English language arts and math. This area of principal learning is focused on implementing the new state standards, selecting effective curriculum strategies and materials to raise student achievement, and supporting the development of higher-order thinking skills.

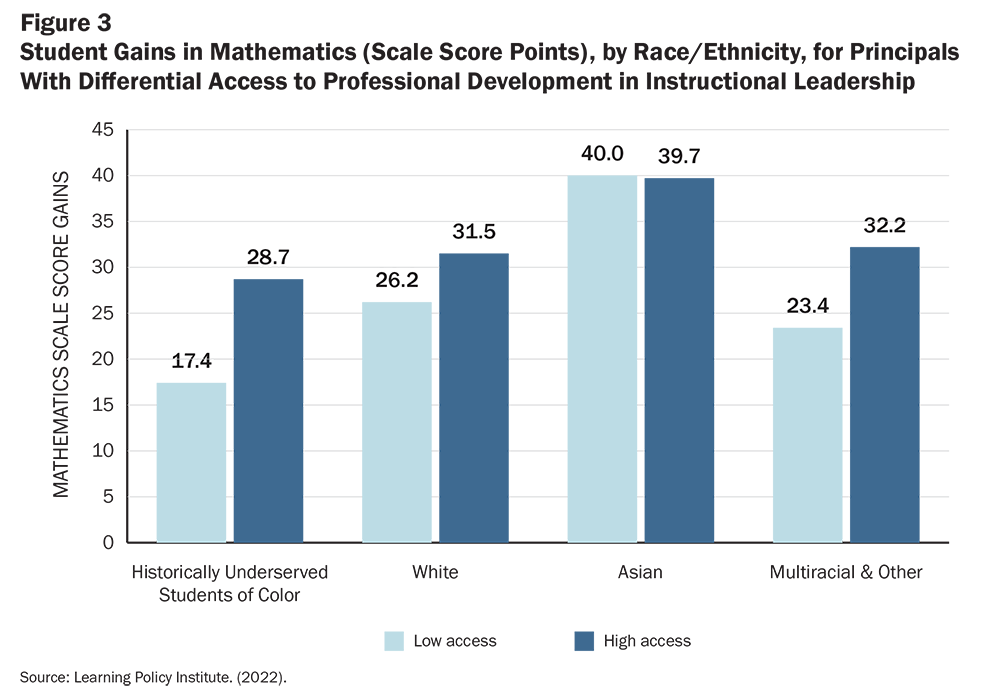

Furthermore, the benefits of this training are most pronounced for historically underserved students of color, defined here as Black, Latino/a, and Native American students, based on the state’s demographics and achievement trends.

The differences in outcomes can be quite large. For example, as shown in Figure 3, we modeled the differences in student outcomes for those whose principals had different access to this kind of professional development, holding constant other characteristics of the principals, teachers, students, and schools. Students from a school where the principal had little access to professional development focused on instructional leadership would lag behind—by a considerable margin—similar students in a comparable school led by a principal who had the highest level of access to this area of learning. Based on the factors of this scenario, mathematics scale scores for historically underserved students of color would be more than 11 points higher in the second school than those of similar students in the first school, a differential of nearly 4 months of instruction. These differentials are also significant for white students (an estimated 5.3 points) and those categorized as “Multiracial & Other”—defined as multiracial or race not reported—(an estimated 8.8 points), while the scale scores of Asian students in these two schools are roughly the same.

The greater gains for historically underserved students suggest that principal professional development focused on instructional leadership may play a key role in reducing racial/ethnic opportunity gaps.

Boosting the Effectiveness of Early-Career Principals

While all students appeared to benefit from principals’ access to professional development, it seems that principals’ learning opportunities were especially important for early-career principals, whose students experienced the largest relative achievement gains. For this analysis, principals were divided into three categories, based on their years of experience on the job. The principals were categorized as:

- Early-career, having fewer than 4 years of experience as a principal

- Mid-career, having 4–9 years of experience as a principal

- Veteran, having 10 or more years of experience as a principal

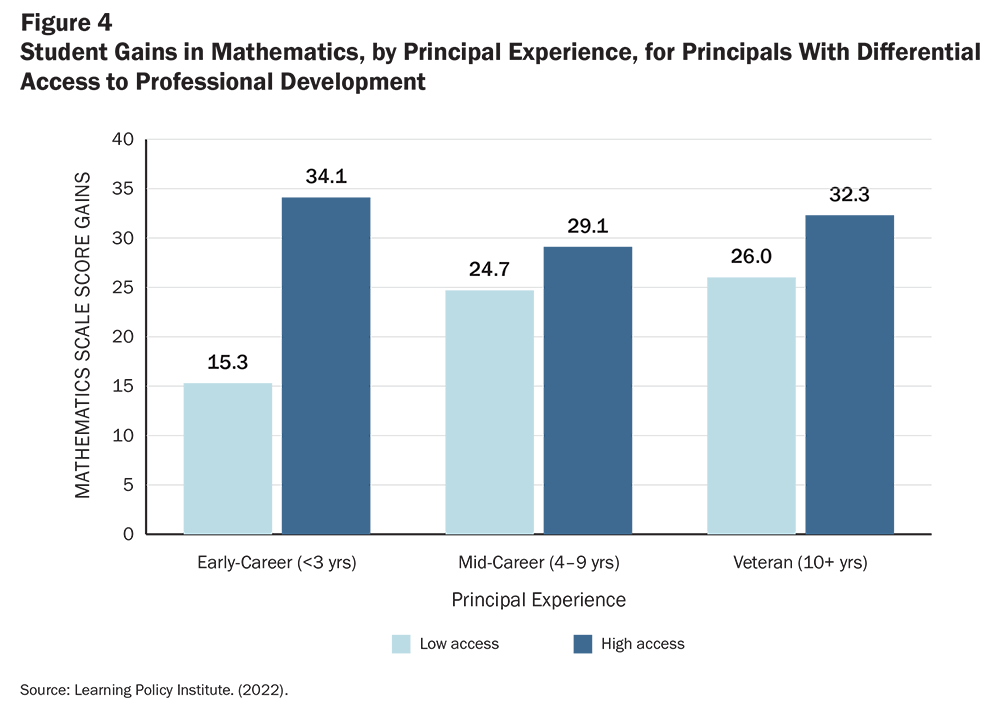

Unsurprisingly, students whose principals had higher access to professional development made greater gains in mathematics than students whose principals had less access to professional development. Although this was the case for students led by principals in all three career categories, the gains were most substantial for students of early-career principals. (See Figure 4.)

Achievement gains in mathematics for students were especially pronounced when early-career principals had experienced higher-frequency professional development and when early-career principals had received professional development focused on managing change. These components of professional development were also beneficial in influencing gains for students who had veteran principals, but their gains were comparatively smaller, as principals with more years on the job have more experience overall and can rely on other sources of knowledge as they work on school improvement.

In earlier analyses, Learning Policy Institute researchers reported on the areas in which California principals would like more opportunities for professional development. Nine out of 10 flagged instructional leadership that focuses on how to develop students’ higher-order thinking skills. In addition, similar proportions wanted more professional learning opportunities focused on:

creating a school environment that develops personally and socially responsible young people and uses discipline for restorative purposes;

- redesigning school structures to support deeper learning for teachers and students;

- leading schools that support students’ social and emotional development;

- leading a schoolwide change and using data to improve student achievement;

- developing systems that support children’s physical and mental health; and

- designing professional learning opportunities for teachers and other staff.Sutcher, L., Podolsky, A., Kini, T., & Shields, P. M. (2018). Learning to lead: Understanding California’s learning system for school and district leaders. Learning Policy Institute.

The strong desire for more professional learning suggests that principals feel their effectiveness improves when they have such opportunities.

In other analyses, our research team discovered that California principals have greater and more equitable access to high-quality preparation and professional development than most principals nationally, in large part as a function of recent reforms of principal preparation, licensing, and accreditation, along with substantial investments in professional development.Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M. E., Levin, S., Leung-Gagné, M., & Tozer, S. (2022). Developing effective principals: What kind of learning matters? [Report]. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/641.201 More recently, the state has designed and implemented an Administrator Performance Assessment as part of preservice preparation and launched a 21st Century California School Leadership Academy to provide ongoing learning opportunities. Future research exploring the relationships between these initiatives and principals’ effectiveness would be instructive.

Conclusion

This new analysis adds to our understanding of the impact of specific qualities of professional learning for principals. It also provides further evidence that principal learning matters for both teacher and student outcomes.

Teachers in schools served by well-prepared principals are less likely to transfer or quit the profession than teachers in schools served by less well-prepared principals. One way to interpret these findings is that high-quality preparation programs—defined in part by the quality of the internships principals experience—may prepare principals to create a supportive, collegial environment that encourages teachers to stay. In addition, principals who experience higher-quality internships during their preservice preparation lead schools where students make greater year-to-year gains in English language arts, compared to students in schools in which principals do not experience high-quality internships.

Furthermore, greater access to in-service professional development is associated with gains in both English language arts and mathematics, with particularly large gains for students in the schools of early-career principals and for historically underserved students of color. In-service professional development programs, especially those focused on instructional leadership, appear to help principals develop specific means to support teaching and learning for those furthest from opportunity.

Finally, the findings suggest that principal professional development can be a key factor in helping early-career principals more quickly reach the effectiveness levels of their more experienced peers. These findings present promising evidence that principals’ engagement in high-quality preservice and in-service learning opportunities has positive effects on the teaching force and students’ academic achievement.

Principal Learning Opportunities and School Outcomes: Evidence From California by Ayana K. Campoli and Linda Darling-Hammond with Anne Podolsky and Stephanie Levin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by a grant from The Wallace Foundation, with additional support from the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.