District Support for Community Schools: The Case of Oakland Unified School District

Summary

This study examines the district infrastructure that Oakland Unified School District (Oakland Unified) developed to support its community school and whole child education practices. The findings indicate that Oakland Unified provided centralized support for community schools, including coordination of partnerships between schools and county-level agencies; management of partnerships between schools and service providers; training for specialized personnel, such as community school managers and student support teams; professional learning for school staff; and resources for family engagement. The implications highlight promising lessons learned for education leaders looking to build, implement, and sustain high-quality community schools in policy and practice.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

Introduction

Community schools integrate a range of supports and opportunities for students, families, and the community through a set of partnerships between the education system, the nonprofit sector, and local government agencies. They are an evidence-based strategy for implementing whole child education, which addresses the full scope of children’s development across multiple domains—including academic, physical, psychological, cognitive, social, and emotional learning.

Across the United States, policymakers, educators, and community members increasingly support community schools as a method of strengthening whole child outcomes. Several states—including California, Illinois, Maryland, New Mexico, New York, and Vermont—have made significant investments in community schools and whole child services, such as the grants offered through California’s $4.1 billion Community Schools Partnership Program.California made a one-time investment of $3 billion in the California Community Schools Partnership Program in the 2021–22 state budget using general fund dollars and then added $1.1 billion in one-time funding in the 2022–23 state budget. See: Fensterwald, J. (2022, May 13). California set to launch hundreds of community schools with $635 million in grants. EdSource. Federal policymakers have increased investments in both full-service community schools and the services they coordinate, such as health and mental health services for children.Ujifusa, A. (2021, October 18). U.S. senators tee up big boost in school funding for next year. Education Week. With such historic investments in community schools, it is important for educational leaders to understand how to build, implement, and sustain high-quality community schools in policy and practice.

What Is a Community School?

The work of building and maintaining community schools is not exclusively school-level work; districts can play an essential role in scaling and sustaining community school implementation. Existing district-led community school initiatives can provide helpful examples of strategies that have supported the design of community schools.

Oakland Unified School District is an important and relevant case for investigation because it is a long-standing, full-service community schools (FSCS) district that intentionally links whole child education to its community schools initiative. Additionally, the district has improved student outcomes in the decade following the launch of its community schools initiative—including a 13% increase in the district’s graduation rate and a 4% reduction in the district’s suspension rate—suggesting that district-level practices in Oakland Unified are worthy of examination.

Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of California’s San Francisco Bay Area, with one of the most diverse racial, ethnic, and linguistic demographic profiles in the country. As in many other large, urban communities, racial and economic inequities are prevalent in Oakland and deeply impact the district’s schools. Oakland has a long history of participation in community organizing, activism, and civic engagement, with educational justice often at the center. These experiences helped to establish the foundational underpinnings upon which Oakland Unified’s FSCS initiative was built.

Drawing on interviews, observations, and publicly available school data about school outcomes, this study explored the district infrastructure that supports whole child education practices at three Oakland community schools: Bridges Academy at Melrose, an elementary school; Urban Promise Academy, a middle school; and Oakland High School. Additionally, this study leveraged findings from a longitudinal study of Oakland Unified’s FSCS initiative to provide a rich context for district community school development over time. Analyses indicate that Oakland put into place structures that supported sustainment of the community schools initiative over time and developed a district infrastructure that enabled their community schools to enact practices that attend to the whole child.

Structures for Sustainment

The Oakland School Board unanimously adopted Oakland Unified’s Full-Service Community Schools (FSCS) initiative in June 2011, marking the district’s commitment to becoming the nation’s first FSCS district. Although there were many setbacks in the initiative’s first decade—including a high turnover of superintendents and periods of lean funding—the district has maintained its commitment to a community schools vision and has been able to sustain its FSCS initiative through the following actions:

- engaging in an extended visioning process that included a broad range of school and community actors and continuing to engage a wide range of stakeholders;

- blending and braiding multiple state, federal, and philanthropic funding sources;

- creating a master agreement between the district and the county, which outlined clear roles and held agencies accountable to their joint efforts; and

- enacting and documenting formal policy commitments—such as school board resolutions and strategic plans—to create institutional memory and establish community schools as a stable part of district infrastructure.

From the outset, Oakland Unified embraced whole child education and a focus on equity as the guiding principles of its community schools initiative. Changes to district structure and policies helped strengthen its community schools work and facilitate a whole child approach.

District Infrastructure Supporting Community Schools

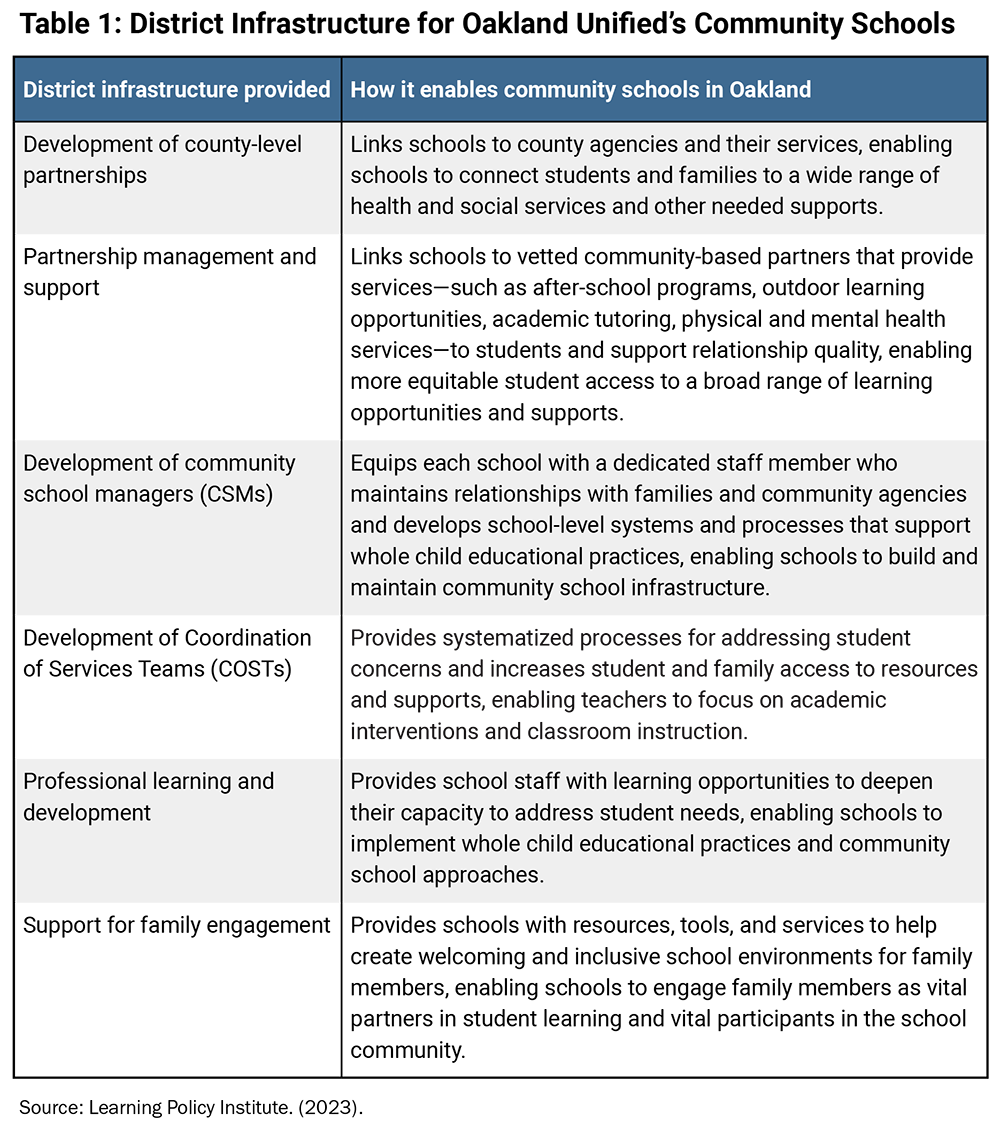

In this section, we describe the central aspects of Oakland Unified’s systems and structures that support schools in the district to function as community schools. Key aspects of district infrastructure include coordination at the county level, management of external partners, establishment of community school managers (CSMs) and Coordination of Services Teams (COSTs), and support for professional development and family engagement. (See Table 1.) At the school sites studied, this district infrastructure allowed schools to implement practices that support whole child education.

Building County-Level Partnerships

Oakland Unified developed a partnership with Alameda County that enables them to work together to support children and families. The collaboration between the district and the county was formalized in 2004 with a master agreement that outlines each entity’s obligations, roles, and responsibilities.

Oakland Unified uses the county-level partnership to provide a range of integrated services and supports for students and their families. For example, the district has employed a liaison that works with the Alameda County Probation Department to support a smooth transition for students who are leaving the juvenile justice system and reentering the school system. Oakland Unified also collaborates with the Alameda County Social Services Agency to ensure that all students and families in need of free or reduced-price lunch are identified and enrolled in social services such as Medi-Cal, CalFresh, and Covered California.

The most developed collaboration between the district and the county is the joint work of the district and the Alameda County Health Care Services Agency (HCSA), the county’s public health department. HCSA was an important thought partner during the district’s strategic planning process to develop the FSCS initiative, and the partnership ensured that the initiative centered the health and wellness of young people. HCSA has continued to work closely with Oakland Unified while the district has built the infrastructure to implement its FSCS initiative. HCSA also manages 16 school-based health centers in Oakland Unified, which offer primary care services, including physical exams, immunizations, reproductive health services, and urgent care.

The master agreement outlines several other areas of collaboration between HCSA and Oakland Unified, including health insurance enrollment; health care internships; transitional supports for students who are in foster care, are refugees, are experiencing homelessness, or are unaccompanied minors; and capacity building for school and district staff to support the health and wellness of students and families. By providing these essential services for students and families, schools can address student and family health issues preventively, before those issues interfere with student learning.

Centralizing Partnership Management and Support

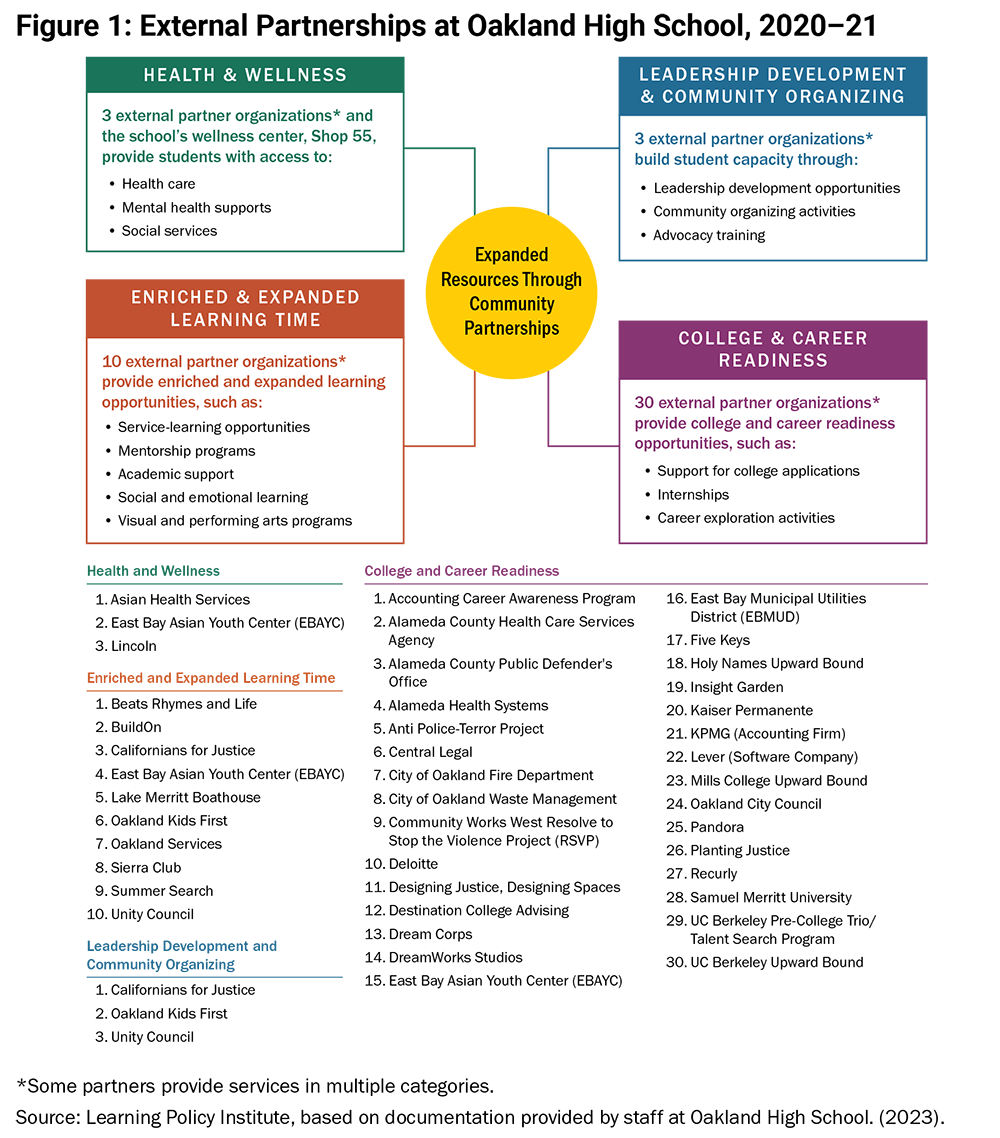

Partnerships with community-based organizations enable community schools to achieve their foundational aim of serving the whole child. Through partnerships, community schools provide a range of programs and services, such as electives offered during the school day; academic supports, such as small-group instruction and tutoring; physical, dental, mental, vision, and reproductive health services; college readiness activities and programs; service-learning opportunities; and after-school programming. For example, Figure 1 shows the wide variety of expanded resources that are offered at Oakland High School through partnerships with more than 40 external organizations.

Developing and managing external partnerships is essential for community schools, but it also places additional administrative burdens on schools. Prior to the community schools initiative, each school had to find and develop its own partnerships. When all responsibility for partnerships rested at the school level, high-capacity schools—which were often the most advantaged—benefited, while many school communities in need of services were unable to obtain partnership support. Now, Oakland Unified provides administrative and capacity-building support for the district’s many partnerships. Centralizing the partnership process allows the district to better track, regulate, and support more equitable partnerships across the district. Additionally, it removes a major administrative burden from school sites, as central office staff assist with tasks such as approving new district partners, onboarding new partnership agencies on a quarterly basis, and maintaining a database of all district partnerships.

The district has also developed a set of resources to support quality collaborations between schools and partner agencies. These include a Partnership Assessment Rubric, which provides language and tools to facilitate discussions at the school level about the role of partner organizations in supporting school endeavors, as well as an annual Letter of Agreement—a companion document to the partnership rubric and the formal memorandum of understanding—which prompts discussion and agreement on specific aspects of the partnership on an annual basis. The district has also developed a tool to support annual evaluations of partnerships, which prompts reflections (with Likert scale ratings and open responses) on key areas outlined in the Letter of Agreement, such as outcomes and achievements, partnership meetings, communication, and problem-solving.

Developing Effective Community School Managers

Becoming a community school requires expanding the functions within the school, which necessitates new processes, structures, and work streams. For many schools in Oakland, the community school manager (CSM) position is what allows schools to build and maintain the infrastructure needed to sustain these areas of work. At the time of this study there were CSMs on staff in 49 of Oakland’s 80 schools. The CSM plays a host of roles related to managing and integrating community school elements, depending on the school and community needs. Under Oakland Unified’s FSCS policy, the district has brought coherence to the CSM role and has provided critical professional development support for CSMs in the district.

Oakland Unified’s community school leadership coordinator is responsible for supervising and supporting all the CSMs in the district. Along with other district staff, she has developed a shared understanding of the CSM role across the district by articulating five core areas of work that fall under a CSM’s purview: (1) family engagement, (2) Coordination of Services Teams, (3) attendance, (4) health access, and (5) partnerships. Though these five areas of work are central to the CSM role in Oakland, the CSM position looks somewhat different from school to school; the position is designed to be adaptive and responsive to the needs of particular school sites.

In addition to bringing districtwide coherence to the CSM role, an important school-level support that the district provides is the hiring and “matching” of CSM candidates. The district screens all the candidates for open CSM positions and then forwards the top three candidates to the school for interviewing and a final hiring decision.

Supporting Effective Coordination of Services Teams

Most schools across the country today have some kind of process for identifying students in need of additional supports; however, these referral processes can be fraught with confusion and administrative burdens. The referral processes often place a heavy burden on teachers to identify and respond to concerns about students, particularly in schools serving communities with high degrees of poverty, trauma, and related health concerns. Coordination of Services Teams (COSTs), a flagship practice of Oakland Unified’s community schools initiative, seek to remedy these challenges by introducing a systematic process that school staff can use to address student concerns. COSTs are crucial for bringing together many of the moving pieces within community schools, including community partners, school administrators, teachers, and CSMs. These teams work to implement the community schools approach by increasing access to resources and supports.

Oakland Unified has systematized and supported COST development at all school sites throughout the district. This included training and support for CSMs, who are often tasked as COST facilitators. Oakland Unified developed a “COST toolkit” for schools, including job descriptions for the COST coordinator, tips on sharing data and maintaining confidentiality, sample agendas, and rubrics to measure success. The district also provided ongoing coaching to partners and CSMs and dedicated multiple professional learning community sessions (described in the following section) to building CSM capacity to effectively manage their sites’ COSTs. Additionally, with input from the CSMs (via monthly professional learning community sessions), the district’s Research, Assessment, and Data team developed template documents for tracking student referrals, follow-ups, and outcomes.

In Oakland Unified community schools, teachers, administrators, partners, and even students and parents can refer students to COSTs to address various types of concerns, such as low attendance, academic challenges, or behavioral struggles. In a 2018 survey of Oakland Unified teachers, 72% reported that they use COSTs to refer students in need of services. COSTs provide teachers with a clear channel to address student needs and access resources, which helps alleviate barriers to student learning while allowing teachers to focus on academic interventions and classroom instruction.

Providing Professional Learning and Development

Oakland Unified has created learning opportunities for school staff to deepen their capacity to address complex student needs and to support the unique dimensions of community school approaches. These include coaching and mentorship, interschool learning communities, and professional development opportunities.

Coaching and mentorship are particularly valuable for personnel in unique school positions without peers who share similar responsibilities. For example, at the start of the school year, the community school leadership coordinator works with each CSM to assist in the development of their annual work plan. Throughout the year, the coordinator meets monthly with each CSM. The specifics of district coaching vary by school and the needs of individual CSMs. For school sites that have a CSM for the first time, these meetings can be instrumental in setting expectations and defining priorities, especially if school leaders have limited experience with the community school model. For seasoned CSMs, the meetings provide a helpful sounding board to refine plans and receive up-to-date information about relevant district resources that they can bring to their sites. The district also provides coaching for other school roles, such as COST leads and attendance liaisons. The CSMs interviewed for this study expressed that their access to informal and formal coaching has been critical to their success in supporting students and families.

Additionally, the district facilitates professional learning communities for CSMs and principals. The professional learning communities provide a consistent opportunity for staff across the district to step away from the demands of their daily school lives to reflect on practice, share experiences, and engage with district personnel. District staff from other departments or groups often attend these meetings to share new systems and developments. The professional learning communities enable schools and staff to continuously improve their community school approach and whole child educational practices, and interviewees for this study expressed that these opportunities helped them to navigate the unique terrain of their roles.

Oakland Unified also provides professional development on a range of topics related to student and family well-being. Training opportunities include topics such as culturally responsive Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, trauma-informed approaches, restorative justice, social and emotional learning, and multi-tiered systems of support. To support these professional development opportunities, district staff have developed various tools, guides, and manuals, such as a social and emotional learning playbook and a restorative justice implementation guide.

Systematizing Support for Family Engagement

Family engagement is a critical practice for community schools; however, developing and implementing effective engagement strategies can be difficult for schools. To mitigate this barrier, Oakland Unified provides schools with dedicated resources to support family engagement at the school level, enabling schools to engage family members as vital partners in student learning and vital participants in effectuating the community schools approach.

The district developed several tools to guide schools in their family engagement efforts. For example, the district has articulated a family engagement theory of action that encompasses multiple dimensions of engaging families, such as creating welcoming and inclusive school environments for families, providing services to support family members, and including family members in shared governance and decision-making. The district has also developed standards for meaningful engagement and a rubric for evaluating school-site family engagement.

Oakland Unified has also worked with schools to build their capacities to engage families in local “school site councils,” the school entities responsible for determining school spending (also a legal requirement of all schools receiving federal Title I dollars). District staff work with school sites to build both parent and school capacities to facilitate family participation in school site council governance. This involves providing trainings for families on topics such as school budgeting, priority setting, and accountability mechanisms. It also involves coaching school leaders and school site council members in creating participatory and inclusive spaces.

Additionally, the district has developed core practices to support family engagement, such as parent–teacher home visits. The district provides training for teachers on how to conduct home visits, with the aim of improving teacher–family relationships by increasing levels of trust and accountability. Home visits are voluntary for educators and families and are in place in nearly 40 schools across the district.

Implications for Districts

Oakland Unified’s Full-Service Community Schools initiative illustrates how districts can sustain community school efforts over time and support schools in functioning as community schools through the development of district- and school-level infrastructures. Findings from this study elevate key considerations that can inform community school implementation in a wide range of settings:

- Developing a district-level infrastructure to facilitate partnerships. Districts with large numbers of community schools can develop an infrastructure that facilitates community school and whole child approaches at the school level by centralizing partnership processes that allow schools to offer integrated supports and by increasing cross-sector collaboration through county-level partnerships. Community schools in this study offered a wide range of services to their students, such as increased access to physical and mental health services and after-school learning opportunities that complemented the traditional school day. The provision of these services can be facilitated by district-level efforts that remove administrative burdens from schools, allowing them to work with large networks of community partners.

- Developing school-level roles and structures that support service delivery. Districts with large numbers of community schools can support schools by bringing coherence to staff roles (e.g., community school managers) that are needed to manage new work streams, such as managing school partnerships. Additionally, districts can support schools by developing universal systems that allow school teams to efficiently match students and families with needed resources, such as Coordination of Services Teams. Providing professional learning and networking for these service providers gives them the opportunity to learn common practices and expand their expertise by sharing what they have learned in their work and engaging in joint problem-solving.

- Building the capacity of school staff to enable the school to function as a community school. Because staff at community schools must embrace new structures, work streams, and dispositions, districts can support schools by building staff capacity through professional learning opportunities. Oakland Unified provides numerous opportunities for professional learning, including coaching and mentorship for principals and other staff, interschool learning communities, and training on various topics related to student and family well-being (e.g., trauma-informed approaches and social and emotional learning).

- Engaging families in decision-making. Districts can support schools to engage families by developing core practices, such as parent–teacher home visits, as well as resources to build the capacity of schools and family members to participate in school governance. These practices are strengthened when they are nested within a district that articulates a vision and theory of action for family engagement and inclusion.

While the case study featured in this brief is a large, urban district, these implications are likely applicable to districts of various sizes and in a wide range of settings. In the case of small and rural districts, some of the district functions and supports identified above—for example, developing master agreements with county agencies to provide school-based services or developing a community of practice for community school managers—may be handled best by a county office of education or by a consortium of districts that collaborate to increase access to services. However, districts of all sizes and settings may benefit from systems-level infrastructure designed to support site-level community school success.

Conclusion

Recent investments in the community schools approach at the federal and state levels forecast an expansion of community schools and community school initiatives across the country. This funding will be maximized if it prioritizes developing district- and school-level infrastructure that can support community schools’ implementation over time.

The Oakland Unified Full-Service Community Schools initiative is a helpful example for illustrating how a district has developed policies and practices that support community schools. Other districts interested in developing and implementing community schools can look to this initiative for lessons learned, strategies, and approaches to building district-level infrastructure.

District Support for Community Schools: The Case of Oakland Unified School District (brief) by Sarah Klevan and Kendra Fehrer is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.

Cover photo by Allison Shelley for All4Ed.