Creating the Conditions for Children to Learn: Oakland’s Districtwide Community Schools Initiative

Summary

Oakland Unified School District (Oakland Unified) in California has made whole child education central to its community schools initiative. Oakland Unified’s community schools provide a wide range of services for children and promote practices that enhance child development. This study finds that Oakland Unified intentionally created infrastructure to support its community schools, including coordination of partnerships between schools and county-level agencies; management of partnerships between schools and service providers; training for specialized personnel, such as community school managers and student support teams; professional learning for school staff; and resources for family engagement. The study illustrates how these district-level supports enabled whole child educational practices within three case study schools.

The report on which this brief is based can be found here.

Introduction

Community schools partner with local organizations and family members to integrate a range of supports and opportunities for students, families, and the community to promote whole child educational approaches that attend to students’ physical, social, emotional, and academic well-being. Community schools typically incorporate four key pillars: (1) integrated student supports, such as mental and physical health care and other wraparound services; (2) enriched and expanded learning time and opportunities, including lengthening the school day and year as well as enriching the curriculum through student-centered learning; (3) active family and community engagement that includes service provision and meaningful partnerships with family members; and (4) collaborative leadership practices that coordinate school services and include school staff, families, and community actors in decision-making.

Community schools are an evidence-based strategy for implementing whole child educational approaches. Research shows that community schools can generate a collaborative and equitable approach to education and a range of positive outcomes, particularly among students from marginalized groups. These include improved attendance, academic achievement, and graduation rates as well as reductions in racial and economic opportunity gaps. The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated long-standing systemic inequities in schools and highlighted the importance of whole child education and supports. As districts look to help students recover from the pandemic and succeed in college, career, and life, a whole child approach to education will be critical.

Across the United States, policymakers, educators, and community members increasingly support community schools as a method of improving whole child outcomes. State policymakers have made significant investments in this strategy, such as the grants offered through California’s $4.1 billion Community Schools Partnership Program. Other states—including Illinois, Maryland, New Mexico, New York, and Vermont—have also grown their investments in community schools and whole child services. Federal policymakers have increased investments both in full-service community schools and in the services they deploy, such as physical health and mental health services for children.

With historic investments in the community schools approach at the federal and state levels, educational leaders can benefit from learning how to build, implement, and sustain high-quality community schools in policy and practice. The study on which this brief is based helps to build this understanding by examining the relationship between district support, community schools, and whole child educational practices within the Oakland Unified School District (Oakland Unified) in California.

This Study

While previous studies have examined community school implementation, they have typically described the work within individual schools, such as community-based organization partnerships and expanded learning time, without attention to how district-level infrastructure is structured to support community schools. A primary focus of this study is on the district-level supports in the Oakland Unified School District that enable successful school-level approaches. Additionally, unlike other studies, this study places a particular focus on understanding how district infrastructure supports community schools to implement the full range of whole child educational practices.

Oakland Unified is an important and relevant case for investigation because it is a long-standing, full-service community schools (FSCS) district that intentionally links whole child education to its community schools initiative. Additionally, since the launch of its community schools initiative the district has improved student outcomes, which suggests that the district-level practices in place in Oakland Unified are worthy of examination. For example, there has been a 13% percent increase in the district’s graduation rate and a 4% reduction in the district’s suspension rate.

To address the study’s research aims, we drew on surveys of students and administrative data about school outcomes, as well as interviews with district personnel and practitioners at three Oakland community schools: Bridges Academy at Melrose, an elementary school; Urban Promise Academy, a middle school; and Oakland High School. We also conducted observations of school events and activities as well as district-led meetings and professional learning community sessions. Additionally, this study leveraged findings from an extensive 8-year longitudinal study of Oakland Unified’s FSCS initiative—including district practices and policies—to provide a rich context for district community schools development over time.McLaughlin, M., Fehrer, K., & Leos-Urbel, J. (2020). The way we do school: The making of Oakland’s Full-Service Community School District. Harvard University Press.

Community Schools and Whole Child Education

Community schools offer far more than the additional external supports they bring into the schools. High-quality community schools integrate a range of whole child educational practices that help transform the learning opportunities and environment of the school.

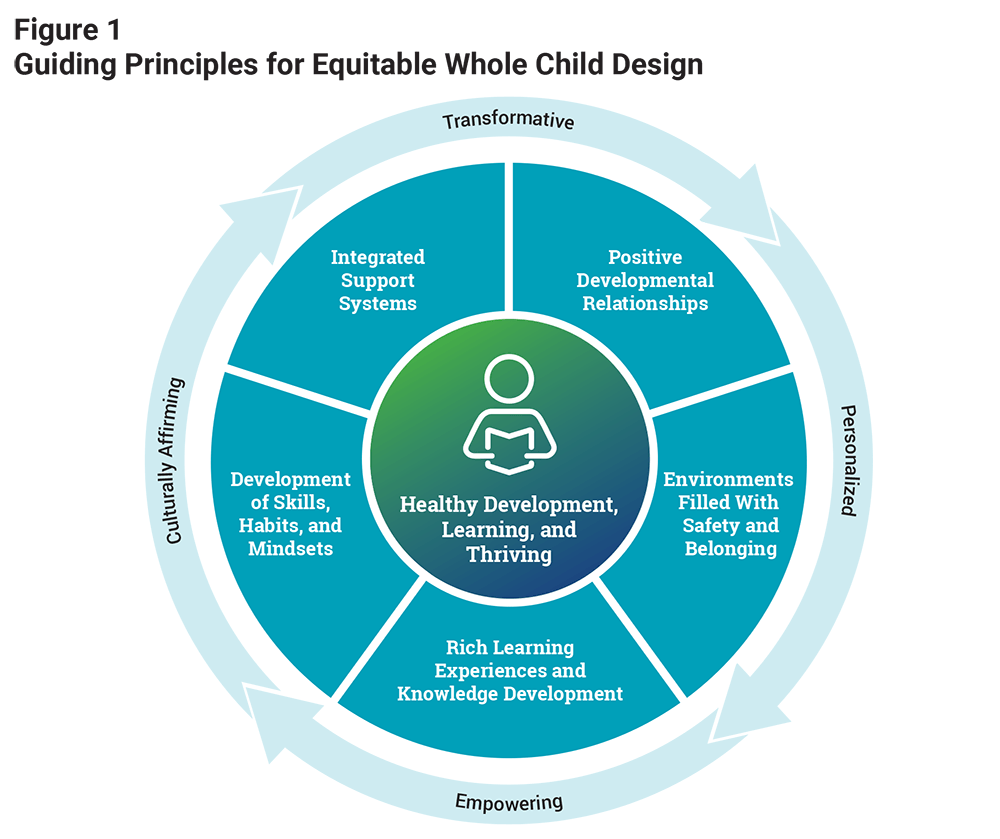

A whole child educational approach is grounded in the science of learning and development. This body of research illustrates the ways in which many factors shape students’ development, well-being, and learning. These factors include in-school conditions, such as the presence or absence of positive relationships, as well as out-of-school conditions, such as the socioeconomic status of the school’s families and neighborhoods. This research demonstrates that the brain is malleable throughout life and that the settings and conditions individuals are exposed to and immersed in affect how they grow throughout their lives. It also suggests that variability in human development is the norm, not the exception; human capacities grow across a spectrum (physical, cognitive, and affective) in interactive ways; adversity affects learning; and children actively construct knowledge based on their experiences, relationships, and contexts. These understandings of how people learn and develop hold implications for the ways we design schools and learning experiences as articulated in the Guiding Principles for Equitable Whole Child Design, which outlines the school structures and practices that can optimize student learning, development, and well-being.Learning Policy Institute & Turnaround for Children. (2021). Design principles for schools: Putting the science of learning and development into action. (See Figure 1.)

The essential principles of whole child education are manifested in schools that include positive developmental relationships in which adults provide care and guidance that enable youth to grow their agency, learn skills, and take on new challenges; environments of safety and belonging in which young people feel physically and emotionally safe in their identities, knowing that they and their cultures are a valued part of the community; rich learning experiences that develop students’ deep understanding and center students by building on their strengths and experiences; the development of social, emotional, and cognitive skills, habits, and mindsets, including executive function, a growth mindset, personal and social awareness, interpersonal skills, resilience and perseverance, metacognition, and self-direction; and integrated support systems that enable schools to meet students’ holistic needs.

The four pillars of community schools can create the conditions for these principles to flourish. Community school pillars such as collaborative leadership and practices and active family and community engagement can orient these schools toward relationship building and inclusive forums that nurture a positive school climate. Dedicated community school managers or directors, who commonly hold positions in these institutions, can also help establish and maintain integrated support systems, making these interventions more accessible, coordinated, and equitable. Finally, with their attention to providing enriched and expanded learning, community schools can create opportunities for young people to engage in an array of learning experiences that pique their curiosity, nurture their full range of skills and habits, and engage them in meaningful and culturally relevant learning.

Oakland Unified’s Full-Service Community Schools Initiative

Oakland is the largest city in the East Bay region of California’s San Francisco Bay Area and has one of the most diverse racial, ethnic, and linguistic demographic profiles in the country, which is reflected in the Oakland Unified student population. Like many other large, urban areas, racial and geographic inequities are prevalent in Oakland and have a deep impact on district schools. Oakland has a long history of participation in community organizing, activism, and civic engagement to address inequities. These experiences helped to establish the foundational underpinnings upon which its full-service community schools (FSCS) initiative was built.

Launched by Superintendent Tony Smith in 2010, Oakland Unified’s FSCS initiative began with a 10-month strategic planning process that involved a wide cross-section of the community. Recommendations from 14 thematic task forces informed the district’s new 5-year strategic plan: Community Schools, Thriving Students. In June 2011, the strategic plan was unanimously adopted by the Oakland Unified Board of Education, marking the district’s commitment to becoming the nation’s first FSCS district.Oakland Unified School District. (2011). Community schools, thriving students: A five-year strategic plan; McLaughlin, M., Fehrer, K., & Leos-Urbel, J. (2020). The way we do school: The making of Oakland’s Full-Service Community School District. Harvard University Press. The principles of whole child education and a focus on equity formed the blueprint of the district’s community school efforts, and these orientations have been intentionally implemented in Oakland Unified’s community schools throughout the past decade.

Although there were many setbacks in the initiative’s first decade—including a high turnover of superintendents and periods of lean funding—the district has maintained its commitment to a community schools vision. Several factors helped Oakland Unified sustain its FSCS initiative, including the following actions:

- engaging in an extended visioning process that included a broad range of school and community actors and continuing to engage a wide range of stakeholders;

- blending and braiding multiple state, federal, and philanthropic funding sources;

- creating a master agreement between the district and the county, which outlined clear roles and held agencies accountable for their joint efforts; and

- enacting and documenting formal policy commitments—such as school board resolutions and strategic plans—to create institutional memory and establish community schools as a stable part of district infrastructure.

Changes to district structure and policies have helped Oakland Unified to strengthen its community schools work and to facilitate a whole child approach.

Infrastructure That Supports Oakland’s Community Schools

Oakland Unified developed key district-level infrastructure that helped the schools in our study implement practices associated with community school and whole child educational approaches.

Support for county-level partnerships. Oakland Unified has partnered with county-level agencies, such as Alameda County Health Care Services Agency, helping to bolster the provision of integrated supports through cross-sector collaboration in schools so that students and families are well connected to the services they need. These county-level partnerships have led to the creation and oversight of 16 school-based health centers throughout the district and have facilitated the provision of additional services for students, such as health insurance enrollment and transitional supports for students living in foster care.

Partnership management and support. Effective partnerships require substantial work, including attention to relationship building, coordination, and management. Oakland Unified’s centralization of some aspects of the partnership process—such as managing a partnership approval process and developing partnership standards—enables schools to provide more programs and services than they could if they needed to negotiate relationships individually. The schools included in this study provide a wide range of services and supports for students’ families on-site, including school-based health services, academic interventions, and mental health services, many of them coordinated by the district.

Supporting effective Coordination of Services Teams. Oakland Unified has made Coordination of Services Teams (COSTs) a universal practice of its community schools. COSTs are school-site teams that systematically connect students and families with needed supports and services. The district has developed a districtwide COST structure and provided schools with resources, such as a COST toolkit, which includes a job description for the COST coordinator, tips on sharing data and maintaining confidentiality, sample agendas, and rubrics to measure success. At school sites in this study, COSTs were essential for efficiently pairing students with mental, behavioral, and physical health supports as well as academic interventions.

Developing effective community school managers. Oakland Unified has implemented the community school manager role, a school-site position that supports community schools and the whole child educational practices within them. Operating as a community school requires an expansion of the school functions, which necessitates new norms, commitments, processes, structures, and work streams. Having dedicated personnel like a community school manager, or similar, allows schools to build the school-level infrastructure needed to support new processes, structures, and areas of work. Oakland Unified has defined five core areas of work for community school managers in the district: including family engagement, attendance support, COST management, health access, and school-level partnership. By defining these core responsibilities and supporting community school managers through professional development, the district plays an important role in bringing cohesion to the role of community school manager.

Professional learning and development. Oakland Unified built staff capacity to implement community schools and whole child educational practices. The district has provided professional development (e.g., coaching, training, professional learning communities) for community school managers and others in unique community school positions (e.g., newcomer social workers who organize supports for recently arrived immigrant students). School staff reported that this capacity building has been essential for their schools’ abilities to function as community schools, has led to significant improvements in school culture and climate, and has facilitated essential supports for a growing population of newly arrived students.

Systematic support for family engagement. As part of its community schools initiative, Oakland Unified developed common tools and processes to promote family engagement. District and school leaders have included family and community engagement in their vision and have enacted structures for local decision-making that include students and families. At the school sites in this study, staff utilized various strategies, including culturally affirming events, parent–teacher home visits, and provision of school information in families’ home languages to engage family members and make them feel welcome in their school communities.

As described below, the district infrastructure enabled schools to adopt whole child practices and increase access to resources and supports for students and families, efficiently connect students and families with needed supports, improve their climate, and build and maintain relationships with families. Educators expressed that their schools’ capacities to provide needed resources effectively, to improve their school climates, and to conduct extensive outreach to families allowed them to focus efforts on teaching and learning. In addition, this infrastructure allowed schools to quickly respond to and meet student needs during COVID-19.

Although the family and community members interviewed for this study were generally appreciative of the schools’ efforts to include them overall, some interviewees expressed an interest in having more involvement in school governance and suggested additional ways that schools could include them—for example, by ensuring that community advisory groups are demographically representative of Oakland Unified families.

Whole Child Education in Practice

Oakland Unified’s community schools initiative has not only built and sustained community schools by providing key resources and support but has also enabled community schools to be designed with an array of whole child structures and practices. At the three schools in this study—Bridges Academy at Melrose (Bridges Academy), Urban Promise Academy (UPA), and Oakland High School (Oakland High)—we found that these educational approaches are incorporated throughout the schools and are intentionally and systematically supported by the district.

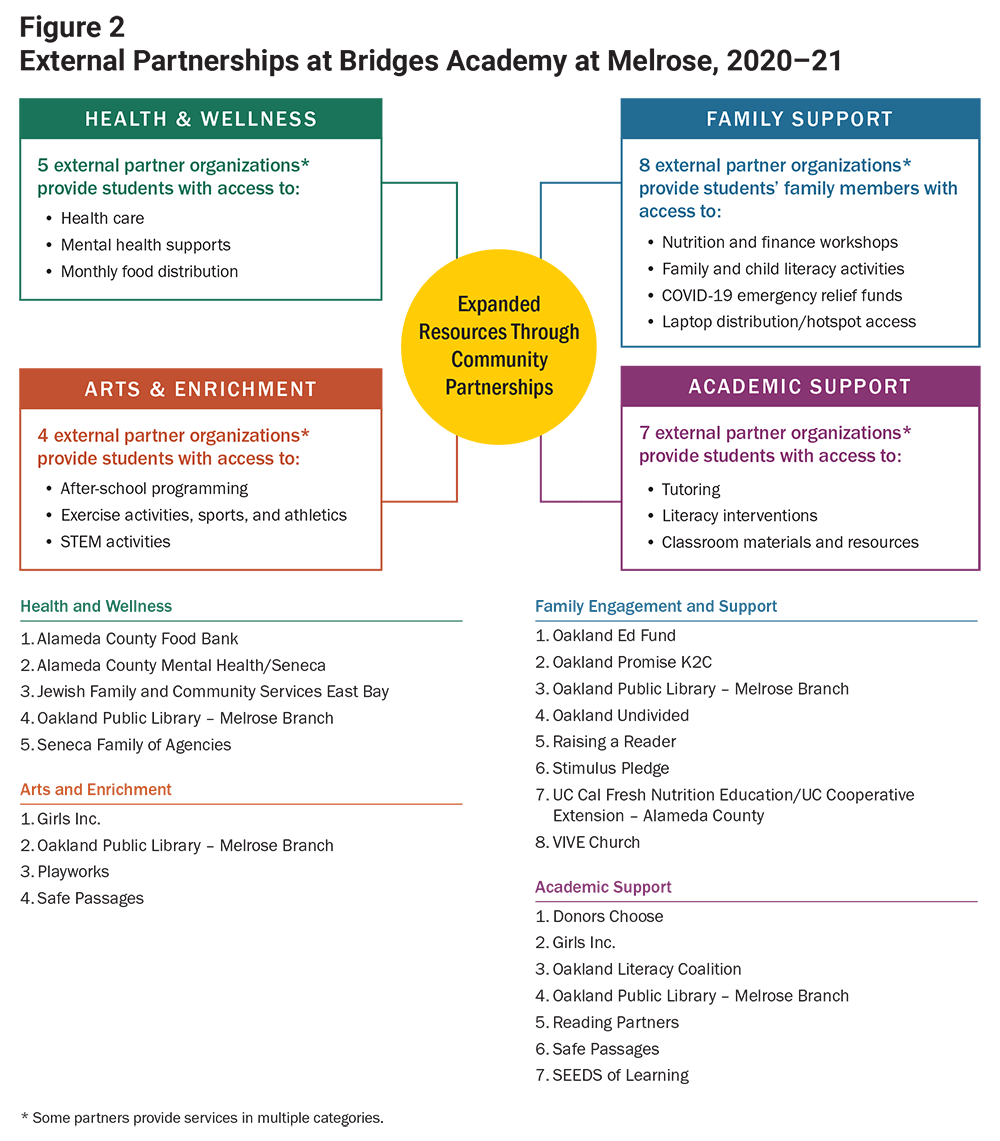

All three schools in this study provided students with integrated support systems, which included a wide range of resources and services. Coordination of Services Teams (COSTs) in all three schools systematically connected students and families to needed services, and wide networks of community partners enabled all three schools to provide expanded programming and services to students and families. For example, Bridges Academy partners with Seneca Family of Agencies to provide a full-time, on-site therapist who works regularly with 20 students. Additionally, Bridges Academy has partnered with the social work program at the University of California, Berkeley, which brings several social work interns to the school to provide services to students. (See Figure 2.) At Oakland High, students have access to a school-based health center that facilitates the provision of a range of health-related services, including sports physicals, dental care, reproductive health services, and mental health counseling.

These types of integrated supports are a pillar of the community schools approach and are a guiding principle of whole child education. Educators interviewed for this study explained that integrated services, as well as processes and roles dedicated to connecting students and families with resources, such as COSTs and the community school manager, freed up teacher time to focus on whole child–aligned curriculum and pedagogy.

The schools in our study received district support for promoting positive relationships throughout their school communities. The schools utilized numerous strategies—such as family conferences, advisory systems, and Linked Learning pathways (small learning academies focused on career pathways that effectively create small schools inside a large high school)—to support the development of positive in-school relationships. At Bridges Academy, the distributed leadership model allowed for many teachers and staff members to participate in school decision-making, which helped build positive developmental relationships among staff. Teachers at Bridges Academy also conducted in-person home visits, which allowed them to see their students in a new context and better understand their lives outside of school. Crew, the advisory program at UPA, was another vehicle for personalizing relationships. The program consisted of small advisory classes that met as a group every morning to eat breakfast together and informally check in with their Crew leader (a UPA staff member), share their experiences, ask questions about school happenings, and listen to school announcements. Crews also met for 1 hour each week for relationship-building activities, and Crew leaders served as primary contacts for students’ families, holding several conferences with each student’s family throughout the year.

All three schools in this study were committed to creating school environments filled with a sense of safety and belonging. At Bridges Academy, fostering a welcoming environment was a central feature of the school’s whole child educational approach. The school hosted several multicultural events, including a multicultural festival where families shared and celebrated their cultural backgrounds. Bridges Academy also prioritized the use of trauma-informed practices, which helped teachers prepare for interactions with students who may have faced traumatic experiences in their lives outside of school. Additionally, both UPA and Oakland High offer several student affinity groups. At UPA, these include an Asian Pacific Islander group, a Mam-speaking group, an African American group, an Afro-Latinx group, two Arab American groups (female and male, as requested by students), and the Gay Straight Alliance. These groups are focused on building community, and they give students a voice in planning events and making changes at the school.

Offering student-centered learning opportunities is one way that community schools can provide rich learning experiences and knowledge development for students. The schools in this study provided many opportunities for project-based learning that incorporated contemporary or local topics, and at the high school level, there were work-based opportunities facilitated by Linked Learning pathways. Each school used culturally affirming curriculum. For example, because of the large percentage of English learners, English language development was a foundational instructional priority at Bridges Academy. The teachers received training in Guided Language Acquisition Design (GLAD), an instructional approach that supports multilingual students in learning content and acquiring new language simultaneously, and the teachers incorporated the use of scaffolds to support students on their distinct learning and language development trajectories. At Oakland High, the student-centered and culturally sustaining curriculum was illustrated through the “lake class,” which was designed around the ecology of Lake Merritt, a short walk from Oakland High’s campus. Students in this class were immersed in hands-on, project-based learning in which they studied the lake and its various water quality factors. They also explored potential policy interventions to improve the health of the lake and presented these at a mock city board meeting.

The three schools in this study implemented strategies to promote the development of skills, habits, and mindsets by infusing their schools with social and emotional learning (SEL) and mindfulness practices and implementing restorative behavioral systems. For example, through a Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports program at Bridges Academy, staff provided students with positive behavioral incentives; set expectations for creating safe, responsible, and respectful settings in the school and in remote learning; and created consistent approaches to supporting and modeling positive behaviors. UPA and Oakland High have also incorporated restorative and educative approaches to discipline at their schools. UPA employed a restorative justice facilitator and a culture keeper, both of whom worked with students to resolve conflicts using restorative conferences and circles, and maintained a Culture Team that focused on developing students’ problem-solving and conflict-resolution skills. Similarly, at Oakland High, teachers used restorative circles and restorative conferences to incorporate SEL into their classrooms and provided opportunities for students to practice interpersonal skills with the support of school adults.

Implications for Schools and Districts

Findings from this study illustrate how districts can support and sustain community schools over time and help schools integrate whole child education and community school approaches. The following implications can inform community school implementation in a range of settings:

- Sustaining community school initiatives. Districts adopting community school initiatives should consider systems and processes for enabling broad-based support among school and community actors; diversifying funding sources; and formalizing plans and commitments through district policy and documentation. Such strategies have sustained Oakland Unified’s initiative through many board and superintendent transitions.

- Developing a district-level infrastructure to facilitate partnerships. Districts can facilitate community school and whole child approaches by centralizing some partnership processes. For example, Oakland Unified has partnerships with Alameda County agencies, such as the County Social Services Agency, to ensure that all students and families in need of free or reduced-price meals are identified and enrolled in social services such as Medi-Cal, CalFresh, and Covered California. The district also centrally manages some partnership processes, which helps schools access and partner with a broad set of community-based organizations to offer integrated supports to students and families.

- Linking whole child education and community school approaches. Oakland Unified’s vision for community schools explicitly links whole child education and community school approaches. The district provides an infrastructure that connects students with resources while enabling educators to center whole child educational approaches that attend to the range of student needs and areas of development. The district prioritizes personalized approaches, such as small learning communities through Linked Learning pathways, positive behavioral supports for students, and professional development and capacity building for school-level staff. Districts and schools can also invest in strategies such as restorative and educative approaches to discipline, student leadership opportunities, and advisories that promote students’ sense of belonging and connection, particularly at the secondary level.

- Developing school-level roles and structures that support service delivery. Districts can support schools by bringing coherence to staff roles that manage new work streams (e.g., community school managers or coordinators); developing universal systems that allow school teams to efficiently match students and families with needed resources (e.g., Coordination of Services Teams); and providing professional learning and networking for staff in these roles and on these teams.

- Building the capacity of school staff to enable the school to function as a community school. Districts can support schools by providing professional learning opportunities to help staff embrace new structures, work streams, and dispositions. Oakland Unified provides coaching and mentorship for principals and other staff, interschool learning communities, and training on various topics related to student and family well-being. These types of learning opportunities supported our study schools in functioning as community schools and in improving their school climates.

- Engaging families in decision-making. Deeply engaging all families and sharing aspects of school governance and decision-making with them is important and challenging and takes time and effort. Districts can support schools with time and training for introducing strategies such as family outreach, conferences with teachers or advisors, and inclusive school decision-making.

Conclusion

Community schools are a research-based strategy for attending to students’ holistic needs. By implementing aspects of the science of learning and development and the key principles of whole child education, community schools support student learning, development, and well-being.

With the community schools approach having gained recognition and support at the federal and state levels in recent years, it is important to understand how high-quality community schools are implemented and sustained. The Oakland Unified Full-Service Community Schools initiative is a helpful example for illustrating a district’s role in developing policies and practices that support a community schools approach. Additionally, practices highlighted at the school level demonstrate how community school and whole child educational approaches benefit students, families, and staff, resulting in positive outcomes for the school community. Other schools and districts that are interested in developing and implementing community schools using whole child educational practices can look to this initiative for lessons learned, site-level design strategies, and approaches to building a district-level infrastructure.

Creating the conditions for children to learn: Oakland’s districtwide community schools initiative (brief) by Sarah Klevan, Julia Daniel, Kendra Fehrer, and Anna Maier is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and the Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.

Cover photo by Allison Shelley for All4Ed.