California’s Special Education Teacher Shortage

Summary

California is in the midst of a severe special education teacher shortage that threatens the state’s ability to improve outcomes for students with disabilities, who often have the greatest needs but receive the least expert teachers. To help policymakers address the shortage, the Learning Policy Institute conducted an analysis of the special education teacher workforce to provide an update on the shortage and its causes. We also reviewed the factors that may be contributing to special education teacher attrition, based on prior research and the perspectives of current special education teachers in California. We conclude with suggestions for evidence-based policy strategies aimed towards resolving the shortage.

This brief is part of a series of research briefs examining special education in California produced by Policy Analysis of California Education.

Introduction

Since 2014–15, California districts have reported acute shortages of special education teachers, with two of every three new recruits now entering without having completed preparation. This shortage means that the most vulnerable students—those who have the greatest needs and require the most expert teachers—are often taught by the least qualified teachers. What can policymakers do to address the shortage and help recruit, prepare, support, and retain these teachers?

To help provide answers, we conducted data analyses and a literature review of the current shortage and its causes. We analyzed data on teacher credentials from the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) and from the 2017 Teacher Education Program Capacity Survey. We complemented our analysis with research on teacher attrition and views from a focus group of nine special educators representing districts across California and classrooms with students of diverse needs and grade levels.

Status of the Shortage: Scope and Severity of the Problem

The field of special education has long been plagued by persistent shortages of fully prepared teachers, due in large part to a severe drop in teacher education enrollments and to high rates of attrition.Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. [Report]. Learning Policy Institute. In addition, California’s steadily growing enrollment of students with disabilities has increased the demand for special education teachers, which worsened shortages. Between 2014–15 and 2018–19, the number of students identified with disabilities increased by 13 percent—from about 642,000 (10.3 percent of the population) to about 725,000 (11.7 percent of the population).California Department of Education. (n.d.). Dataquest. At the same time, as California schools recovered from an era of budget cuts and teacher layoffs, districts’ efforts to restore programs and reduce class sizes also increased teacher demand. Since 2015, shortages have deepened each year, presenting a critical challenge to providing adequate educational opportunities to students with disabilities.Darling-Hammond, L., Sutcher, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Teacher shortages in California: Status, sources, and potential solutions [Report]. Policy Analysis for California Education, Stanford University.

Increase in Substandard Credentials and Permits

A key indicator of shortages is the prevalence of substandard credentials and permits, which are issued to candidates who have not completed the testing, coursework, and clinical experience the CTC requires for preliminary credentials; the latter are issued only to new, fully prepared teachers. By law, districts are expected to hire teachers on substandard credentials and permits only when a fully credentialed teacher is not available.

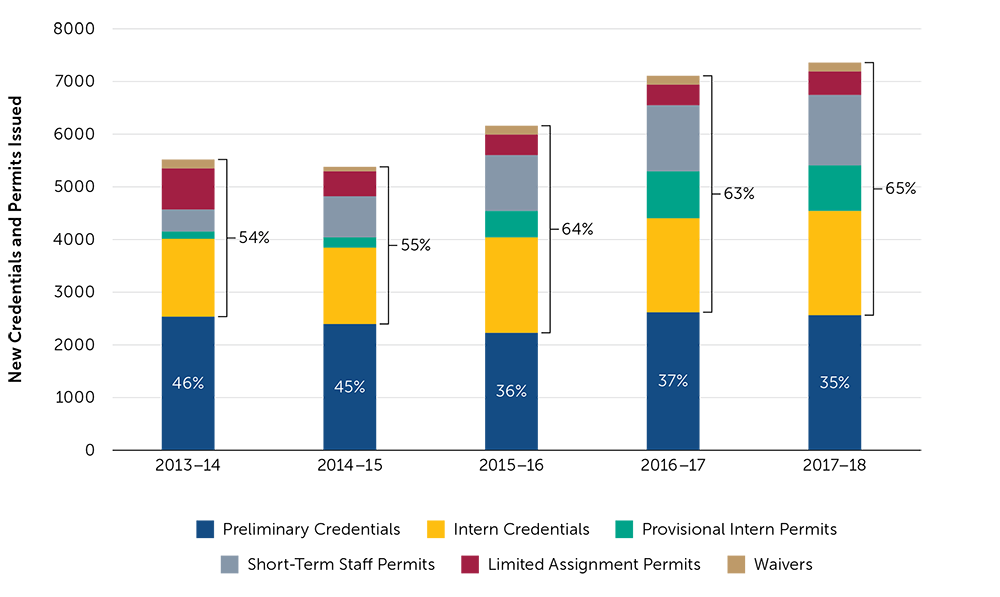

In recent years, the number of substandard credentials and permits issued in special education has grown. According to CTC data, in 2017–18 the state issued 4,776 substandard special education credentials and permits (including intern credentials, provisional intern permits, short-term staff permits, limited assignment permits, and waivers). In contrast, the number of preliminary special education credentials issued to California-prepared teachers has remained mostly flat, with 2,553 issued in 2013–14 and 2,575 in 2017–18 (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. New Special Education Credentials and Permits Issued in California, 2013–14 to 2017–18 (Excluding Preliminary Credentials Issued to Teachers Entering from Out of State)The CTC issues about 500 to 700 special education preliminary credentials annually to out-of-state teachers. California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (n.d.). Teacher supply: Credentials; California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (n.d.). Teacher supply: Interns, permits and waivers.

Note: CTC data on preliminary credentials issued to teachers from out of state are excluded from this analysis.

Decline in Teacher Preparation Enrollments

Declining teacher preparation enrollment contributes to shortages in California. Since 2001, overall teacher preparation enrollments in California for all subjects have declined by more than 70 percent, and the number of special education teachers prepared in pre-service programs has continued to decline, even in the recent era of increased demand.Darling-Hammond et al., 2018. Among those teachers receiving preliminary education specialist credentials, those prepared in traditional pre-service programs declined from 1,557 (51 percent of the total) in 2012–13 to 854 (34 percent of the total) in 2017–18.LPI analysis of data retrieved from California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (n.d.). Teacher supply in California (2012–13 to 2017–18). The remaining preliminary credentials were issued to individuals who completed their preparation through a university or district internship program, meaning they began teaching without having completed their coursework and, in most cases, without having experienced student teaching.

A key question is whether the drop in new credentials is due to a shortage of candidates or an inadequate capacity to train candidates in this field. In an earlier analysis, we found that both teacher qualification requirements and education program capacity may impact teacher preparation enrollments.Darling-Hammond et al., 2018. In a 2017 CTC survey, preparation programs generally reported that while they have capacity to serve more candidates, there are shortages of qualified applicants (presumably those who have passed the necessary prerequisite licensure tests) and inadequate financial incentives to recruit candidates.

Our research showed that, even where there is capacity, restrictions on program enrollments in the California State University system (where slots are often tied to the prior year’s enrollments) may slow programs’ ability to respond to growth in demand. An additional factor for special education is that, over the last decade, more than 30 programs preparing a range of specialists were eliminated, reduced, or placed on moratorium status. Because these programs can be expensive, universities may not be able to maintain them when the supply of recruits is low and adequate recruitment incentives are unavailable.

The Critical Problem of Attrition

While teacher demand is driven by several factors—including growing student enrollment and pupil-to-teacher ratios—the lion’s share of demand is driven by teacher attrition. In California, we estimate that attrition from the profession—which has grown to about 9 percent annually—accounts for about 88 percent of annual demand and drives shortages across subject areas, particularly in high-need schools.Carver-Thomas, D., Darling-Hammond, L., & Kini, T. (in press). The shape of California teacher shortages: A district-level analysis. Learning Policy Institute; Darling-Hammond et al., 2018.

National data show higher attrition rates for teachers in special education than for those in other areas.Sutcher et al., 2016. While it is not possible to calculate turnover rates for California’s special educators in traditional schools from the California Department of Education data file available to us, we calculated turnover for teachers working in special education schools: between the 2015–16 and 2016–17 school years, 13 percent of teachers in special education schools left the profession or state and 7 percent moved between schools within California. Combined, more than one in five teachers in special education schools left their position, more than in any other subject.Darling-Hammond et al., 2018.

Researchers project that over a quarter of California’s special educators who were teaching in 2014 will retire by 2024, more than in any other subject area.Fong, A. B., Makkonen, R., & Jaquet, K. (2016). Projections of California teacher retirements: A county and regional perspective (REL 2017-181). U.S. Department of Education. However, across fields, most attrition is preretirement, caused by teachers leaving the profession early or mid-career.Sutcher et al., 2016. In general, preretirement attrition is driven by teachers’ dissatisfactions with their positions or the profession. For special education, research shows that preparation, training, working conditions, and compensation influence teachers’ career decisions.

Preparation and Professional Learning Opportunities

National research shows that teachers who are more comprehensively prepared feel more efficacious and leave teaching at less than half the rate of those who enter without preparation.Darling-Hammond, L., Chung, R., & Frelow, F. (2002). Variation in teacher preparation: How well do different pathways prepare teachers to teach? Journal of Teacher Education, 53(4), 286–302; Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., & May, H. (2012, May). Retaining teachers: How preparation matters. Educational Leadership, 69(8), 30–34. Our analyses show that this is also true in California across content areas, with teachers on substandard credentials or permits leaving at about twice the rate of those who are fully prepared. Thirty-one percent of teachers on substandard credentials or permits in self-contained classrooms—including special education classrooms—leave annually, compared to 15 percent of their counterparts who are fully credentialed in their fields.Darling-Hammond et al., 2018.

Research also shows that special educators with more intensive preparation and professional learning experiences are less likely to leave their positions and are better prepared to use a variety of instructional methods and to handle other key teaching duties.Billingsley, B. S., & Bettini, E. A. (2019). Special education teacher attrition and retention: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 697–744; Boe, E., Shin, S., & Cook, L. H. (2007). Does teacher preparation matter for beginning teachers in either special or general education? Journal of Special Education, 41(3), 158–170; Nougaret, A. A., Scruggs, T. E., & Mastropieri, M. A. (2005). Does teacher education produce better special education teachers? Exceptional Children, 71(3), 217–229; Sindelar, P. T., Daunic, A., & Rennells, M. (2004). Comparisons of traditionally and alternatively trained teachers. Exceptionality, 12(4), 209–223. In particular, strong mentoring and more time spent student teaching are associated with lower probabilities of attrition; mentors who have special education knowledge are found to improve the instructional practice of novice special educators.Billingsley & Bettini, 2019; Connelly, V., & Graham, S. (2009). Student teaching and teacher attrition in special education. Teacher Education and Special Education, 32(3), 257–269; Cornelius, K. E., Rosenberg, M. S., & Sandmel, K. N. (2019). Examining the impact of professional development and coaching on mentoring of novice special educators. Action in Teacher Education.

High-quality preparation and professional development are particularly needed in California, where the extent and quality of special educator preparation vary more and are less intensive than in other states. In California, special education teachers have been permitted to enter the profession without teaching experience or general education training. Many undergo only a 9-month credential program, and most enter through pathways that do not offer student teaching. In contrast, in many other states, teachers earn a general education teaching credential, often in a 4-year undergraduate teacher education program, and then acquire a 2-year master’s degree in special education. Both experiences typically include extensive coursework and student teaching. In our focus group, teachers spoke about inadequate preparation. For example:

When I went through my credential program, [the information] really wasn’t there specifically addressing the needs of special ed students that I would eventually have in my class.

In California [special educator preparation] … you’re not getting into a classroom. ... I had one class where I did 15 hours of observation; one class had 30. It’s not enough. I think [pre-service teachers] need to be in the classroom more.

Working Conditions

Another issue influencing attrition is the large caseload for special education teachers. Caseload, which is distinct from class size, refers to all the students for whom a special education teacher has responsibility. Nationally, special education teachers say large, high-maintenance caseloads add stress to their work.Hagaman, J. L., & Casey, K. J. (2018). Teacher attrition in special education: Perspectives from the field. Teacher Education and Special Education, 41(4), 277–291; Fowler, S. A., Coleman, M. R. B., & Bogdan, W. K. (2019). The state of the special education profession survey report. Council for Exceptional Children; McLeskey, J., Tyler, N. C., & Flippin, S. S. (2004). The supply of and demand for special education teachers: A review of research regarding the chronic shortage of special education teachers. Journal of Special Education, 38(1), 5–21.

Allowable caseloads are higher in California than in many other states. Although state law limits caseloads for special education resource specialists to 28 students, overages occur, since caseloads can increase up to 32 students with approval of a state waiver.A resource specialist is a special education teacher who typically provides services to students who are assigned to a general education classroom for the majority of the school day. California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2016). Resource specialist added authorization. In contrast, New York, for example, limits the caseload for a resource room teacher (similar to California’s resource specialist) to 20 students, or 25 students for Grades 7 and above.The University of the State of New York, the State Education Department. (2016, October). Regulations of the Commissioner of Education. Pursuant to §§ 207, 3214, 4403, 4404, and 4410 of the Education Law, Part 200 & 201. Further, the law requires that teachers work with no more than five students at a time, and integrated coteaching classrooms (an inclusion setting) are limited to 12 students with disabilities.The University of the State of New York, the State Education Department. (2013, November). Continuum of special education services for school-age students with disabilities: Questions and answers.

Our California focus group spoke a great deal about the challenge of heavy caseloads and large class sizes, which are especially burdensome because of the multifaceted aspects of the job. In addition to teaching, special education teachers must understand and comply with a complex assortment of state and federal special education laws and regulations, as well as district policy. Their nonteaching responsibilities include extensive paperwork and communications with many other professionals as they manage an individualized education program (IEP, also known as an individualized education plan) for each student on their caseload. Teachers explained:

The case manager part … [is] a whole different job on top of teaching that I don’t think people who are not in special education can understand. … It’s not just writing IEPs. We have to communicate with parents more often, and we have to communicate with [the] speech pathologist, all their extra services. All of that takes time.

A typical annual IEP is upwards of 3 hours of preparation. A triannual [review] is at least 9, sometimes a lot more. So, just the time that we are required on our own time, after school, weekends, in order to make sure that all of those are done [is extensive].

Beyond caseloads, a national survey of special education teachers shows that access to resources and professional support to fulfill IEP requirements and goals are key working condition concerns.Fowler et al., 2019. In the same study, many also reported that administrators and their general education peers lack sufficient background in special education to be able to support their efforts and serve students well. Echoing this concern, one focus group participant noted:

[We need] administrators who have some basic training in special education needs and services and in the requirements, because that’s what I hear too from my [fellow special education teachers]. My administrators don’t know special education from Adam, and so they don’t know how to help me service my students.

Collaborative workplaces are especially critical for special education teachers, who must interact with school and district administrators; special and general education teachers; paraprofessionals; and service providers to meet the needs of their students. Special educators who give high ratings for the support they receive from other professionals more frequently express an intent to stay in the field.Berry, A. B. (2012). The relationship of perceived support to satisfaction and commitment for special education teachers in rural areas. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 31(1), 3–14; Billingsley & Bettini, 2019.

Compensation

Finally, compensation matters. While California’s average teacher salaries are high relative to other states, the cost of living in many parts of California is much higher. In a high-cost state like California, inadequate compensation can be an acute challenge for teachers. A recent analysis of California’s teacher salaries and rent prices reveals that in 40 percent of districts reporting salary data, first-year teachers do not earn enough to rent a one-bedroom apartment.Lambert, D., & Willis, D. J. (2019, April 17). Rising rents in coastal California outpace teacher pay. EdSource. A focus group participant discussed this challenge:

I want to say unapologetically, I worked really hard. I graduated from a great university, I’ve been teaching in my district for 8 years with a master’s degree, and I just broke $60,000. You want to talk about support? I need to make enough money to live in [my community]. And that is one of the things driving people out [of teaching].

Faced with high costs in California, individuals interested in teaching may choose other, higher paying career paths. Indeed, research suggests that high levels of college debt drive students away from lower wage professions like teaching. A study of students at a highly selective undergraduate institution found that incurring debt reduced the probability that students chose low-paid “public interest” jobs. The influence of debt on job choice was “most notable on the propensity to work in the education industry.”Rothstein, J., & Rouse, C. E. (2011). Constrained after college: Student loans and early-career occupational choices. Journal of Public Economics, 95(1–2), 149–163 at p. 150.

Other research has found that students of color and those from low-income households carry greater loan debt and perceive student loans as a greater burden than do other students with similar debt and earning similar salaries.Darling-Hammond, L. (2019, November 17). Burdensome student loan debt is contributing to the country’s teacher shortage crisis. Forbes; Baum, S. & O’Malley, M. (2003). College on credit: How borrowers perceive their education debt. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 33(3), 7–19. Our California focus group suggested that reducing costs and debt would help recruit and retain new special educators:

The student loans that these students have, that is just [the biggest challenge]. We live in California, and all these cities are so expensive—San Diego, San Francisco. It’s ridiculous … and then there’s long commutes, and it’s just that financial burden.

Policy Considerations

In recent years, California has begun to address teacher shortages, investing in programs to recruit and retain teachers by helping classified staff become credentialed, starting new undergraduate programs for teacher education, and supporting training for bilingual teachers. In the last 2 years, the state made its biggest investments yet by supporting teacher residencies ($75 million, with $50 million targeted towards special education); local solutions ($50 million) that address special education teacher shortages; and the Golden State Teacher Grant program ($90 million), which will provide service scholarships to recruit new teachers into hard-to-staff subjects like special education.

It will take time to see the impacts of these initiatives, which were all made on a one-time basis in the state budget. Given the severity of the problem, California will likely need to work on special education teacher recruitment and retention over a substantial period to resolve the shortage and prevent it from resurfacing. Research suggests the following evidence-based approaches:

Strengthen the Teacher Pipeline with Recruitment Incentives for High-Retention Pathways

High-retention pathways into teaching—such as teacher residencies and grow-your-own programs that move paraprofessionals into teaching—have proven successful for recruiting and retaining a diverse pool of teachers.Guha, R., Hyler, M. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The teacher residency: An innovative model for preparing teachers [Report]. Learning Policy Institute; Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators [Report]. Learning Policy Institute. Residencies enable candidates to train with expert teachers in a district that will ultimately employ them while earning a credential through a connected university partner. Paraprofessional pathways support individuals who are rooted in communities and have experience working with students, often in special education.

The state has begun to mitigate the financial costs of becoming a special education teacher through investments in the Golden State Teacher Grant Program and teacher residencies. These will also reduce teachers’ debt and thereby effectively increase their compensation. California has also previously benefitted from programs that could be considered for reinstatement, such as the Classified School Employee Teacher Credentialing Program and the Paraprofessional Teacher Training Program.

Improve the Quality of and Access to Preparation

As noted in this report, better prepared teachers are both more effective and more likely to stay in teaching.Billingsley & Bettini, 2019; Boe et al., 2007; Connelly & Graham, 2009; Cornelius et al., 2019; Ingersoll et al., 2012; Nougaret et al., 2005; Sindelar et al., 2004. The CTC is currently overhauling training rules for both general and special education teachers to ensure a stronger base of knowledge and skills for teaching students with disabilities. As California updates licensing expectations for special education teachers and works to increase the number of newly credentialed teachers, it will be important to build and expand the capacity of teacher education programs, as well as support new program designs that provide more intensive preparation and student teaching—and that ensure strong mentoring—to allow new teachers to maximize their chances of success.

Expand and Strengthen Professional Development

Studies show that intensive professional learning experiences are highly valued by special education teachers and are associated with increased teacher efficacy and lower probability of attrition.Billingsley & Bettini, 2019; Cornelius et al., 2019; Gehrke, R. S., & McCoy, K. (2007). Considering the context: Differences between the environments of beginning special educators who stay and those who leave. Rural Special Education Quarterly, 26(3), 32–40; Hagaman & Casey, 2018. The state can support the retention of current special education teachers by providing meaningful professional learning opportunities that help them meet the needs of students with disabilities, such as job-embedded coaching, mentoring, and ongoing support. The recently launched Educator Workforce Investment Grant, which allocated $5 million in 2019 to provide special education–related professional development to teachers and paraprofessional educators, can help improve retention by supporting these types of opportunities. Such funds could also help provide professional development to teacher mentors to ensure they have the necessary special education background to support novice special educators. In addition, all beginning California teachers must complete an induction program to earn their clear credential, and when done well—with one-on-one mentoring by a teacher in the same field—induction can help retain teachers while improving their effectiveness.Podolsky et al., 2016. Currently, however, some districts do not offer induction services since they are not required to do so, and others charge novice teachers for them. These are areas for attention in the effort to retain special educators.

Improve Working Conditions for Special Education Teachers

Poor working conditions, including large caseloads and overwhelming nonteaching responsibilities, may contribute to the attrition of special education teachers.Billingsley & Bettini, 2019; Russ, S., Chiang, B., Rylance, B. J., & Bongers, J. (2001). Caseload in special education: An integration of research findings. Exceptional Children, 67(2), 161–172. California’s caseload caps are very high and frequently waived, so that resource specialists, for example, can be responsible for up to 32 students—far above levels in other states. The state and districts can consider how to revise caseload expectations and provide additional administrative supports to help alleviate overwhelming workloads for special educators and ensure that they have time to comply with federal and state requirements and to work effectively with their students.

The state and districts can also improve working conditions by supporting special education training for general education teachers as well as school and district leaders to improve their understanding of the needs of students with disabilities, and their capacity to support these students and their special educator colleagues. This is particularly critical for ensuring that inclusion of students with disabilities in general education classrooms is done well and leads to improved student outcomes. One resource for this training is the 21st Century California School Leadership Academy, enacted in 2019, which is intended to provide administrators and other school leaders with professional learning opportunities that should include special education.

Increased Compensation

National data suggest that adequate compensation can help districts retain special education teachers.Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it [Report]. Learning Policy Institute. In 2019, California increased state funding for special education and signaled an expectation for additional increases in 2020, which are reflected in the governor’s January 2020 budget. These investments can help relieve fiscal pressure in districts and better position them to support their special education teachers through higher salaries that recognize the costs of living; training and workload management; college loan repayment tied to retention; and other supports, such as housing subsidies.

Conclusion

A common objection to teacher shortage interventions is the belief that the labor market will adjust on its own to meet demand. It is true that teacher supply is dynamic and adjusts as economic and social conditions change. In response to increased demand for special education teachers, districts may seek to improve salaries and working conditions where they have the resources to do so. However, districts cannot produce a pipeline of teachers where none exists, nor can they by themselves improve the quality of training that new teachers receive. Because the shortage emerges from a complex set of challenges, it will require comprehensive, proactive policy solutions that support not only teachers but also the kinds of programs that prepare them and the kinds of workplaces in which they can succeed in meeting the needs of the state’s most vulnerable students.

California’s Special Education Teacher Shortage (policy brief) by Naomi Ondrasek, Desiree Carver-Thomas, Caitlin Scott, and Linda Darling-Hammond is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Sandler Foundation and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.