Felicitas & Gonzalo Mendez High School: A Community School That Honors Its Neighborhood’s Legacy of Educational Justice

Felicitas & Gonzalo Mendez High School (Mendez) is a community school located in East Los Angeles. Named for the plaintiffs in the 1946 landmark desegregation case, Mendez has deep ties to the Boyle Heights neighborhood in which it is located, including a robust network of partnerships that engage and support its students and their families. Staff, families, and partners share leadership opportunities at this 12-year-old community school and provide students with rigorous and engaging academics in a nurturing and inclusive environment.

Mendez at a Glance

Mendez High School is a community school in the Eastside of Los Angeles. Mendez opened in 2009 to relieve overcrowding at neighboring Roosevelt High School. The byproduct of a grassroots campaign for new schools, it was the first high school to open in Boyle Heights in 85 years. Today, Mendez serves 1,013 students: 97% identify as Hispanic or Latino, 94% are socioeconomically disadvantaged, 13% are currently classified as English learners, and 17% are students with disabilities.California Department of Education. (2020). 2019–20 enrollment by ethnicity and grade [School of Math and Science Report 19-64733-0119966, Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez High]. DataQuest. (accessed 03/09/21); California Department of Education. (2020). 2019–20 enrollment by subgroup [School of Math and Science Report 19-64733-0119966, Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez High]. DataQuest. (accessed 03/09/21).

Community organizing laid the foundation for Mendez, beginning with a campaign to establish the first new high school in its neighborhood in 85 years. To reflect the social justice values and cultural heritage of the community, this campaign advocated for the school to be named after the Mendez family. School staff and leadership are quick to connect their mission and vision as a community school to the Mendez legacy. (See “What Is a Community School?”.) Principal Mauro Bautista gives first-time visitors to the school a brief history lesson that draws a through line from the Mendez family’s fight for desegregation to the school’s commitment to providing its students (who are predominantly Latino/a and from low-income families) with equitable education opportunities.

What Is a Community School?

Community schools are schools designed to create a system of partnerships and supports to enable learning and well-being. This approach represents a place-based strategy for school improvement, in which relationships are centered and community organizations partner with schools to deliver resources for mental and physical health care, nutrition, social services, and learning supports that meet student needs. Community schools typically have a community school manager who coordinates partnerships and leverages resources between the school and community-based organizations. Community schools are grounded in an evidence base showing improvement in student outcomes, including attendance; academic achievement; high school graduation rates; reduced racial and economic achievement gaps; and positive school climate, behavior, and social functioning.

This research also shows that implementation matters, with longer-operating and better-implemented programs yielding more positive results. While the specific programs and services vary according to local context, there are four key pillars of the community school strategy:

- Integrated student supports: Community schools provide mental and physical health care, nutrition support, housing assistance, and other wraparound services. This system of support addresses the needs of students and families and is sustained over time.

- Expanded and enriched learning time and opportunities: Students have access to learning well beyond the typical school day, often in a way that expands on and enriches the curriculum and is tied to the real world. This learning often taps into both students’ and the community’s wealth of knowledge. Community partners provide educational programming for students before, during, and after school; during the summer; and on weekends.

- Active family and community engagement: School staff actively engage members of the school community, including families, as partners and leaders. Families and community members take part in school life, from volunteering to learning to sharing their expertise and leading. Schools often leverage existing organizations to support family participation.

- Collaborative leadership and practices: Community schools use structures designed to provide a variety of community stakeholders with a voice in decision-making. School leaders encourage distributed leadership, through which they empower partners, teachers, families, students, and community members to engage with leadership opportunities and exercise power.

Most community schools begin with a needs assessment, such as that which informed the design of Mendez as part of a planning grant for the U.S. Department of Education’s Promise Neighborhoods initiative.

Mendez is part of the Los Angeles Unified Community Schools Initiative, which emerged from the January 2019 settlement of the district’s teacher strike. This initiative established 30 new community schools in the district. Seventeen schools, including Mendez, were part of the initial cohort and received district funding that supported a community school coordinator position as well as integrated student supports, including mental health resources. On July 9, 2020, the Los Angeles Unified School Board passed the resolution Charting Progress and Expanding Support for Community Schools, which will provide funding for the initial cohort of community schools beyond the 2-year pilot. As of August 2021, the district had funded two cohorts of community schools.

The school carries on this legacy with its two signature equity initiatives—AP for All and Computer Science for All—and its school safety strategy that is rooted in relationships and restorative practices, rather than punitive measures. In 2019, as part of the school community’s commitment to restorative practices, students and staff led a movement to end the district’s policy of randomly searching students for weapons as they arrive on campus.

Mendez High School’s community-based and equity- focused practices have made possible an impressive shift in the academic outcomes of students in Boyle Heights. By 2020, just 11 years after the school’s establishment, the graduation rate had reached almost 90%, and the school had a 90% college-going rate.California Department of Education. (2020). 2019–20 four-year adjusted cohort graduation rate [Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez High School Report 19-64733-0119966]. DataQuest. (accessed 04/02/21); Bautista, M. (n.d.). Principal’s message. (accessed 04/02/21). Graduation data from Mendez’s founding year and from Roosevelt High School, which is the high school most Mendez students attended prior to the school’s founding, are currently unavailable, but community organizers estimate that the rates were around 45%. The school has had zero expulsions since 2011, and in 2021 over 75% of students reported feeling safe and happy at Mendez.California Department of Education. (2020). 2019–20 expulsion rate [School of Math and Science Report 19-64733-0119966, Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez High]. DataQuest. (accessed 04/02/21); Los Angeles Unified School District. (2021). LAUSD School Experience Survey results 2020–21. (accessed 07/02/21). They are also engaged as leaders in their school and in their community.

“Mendez is a place where students can be themselves … where students can master anything they want,” noted senior Eduardo Ruiz. Eduardo gained admission to several University of California and California State University campuses, including University of California Los Angeles, and chose to attend California State University in Los Angeles.

Partnerships: It Takes a Village

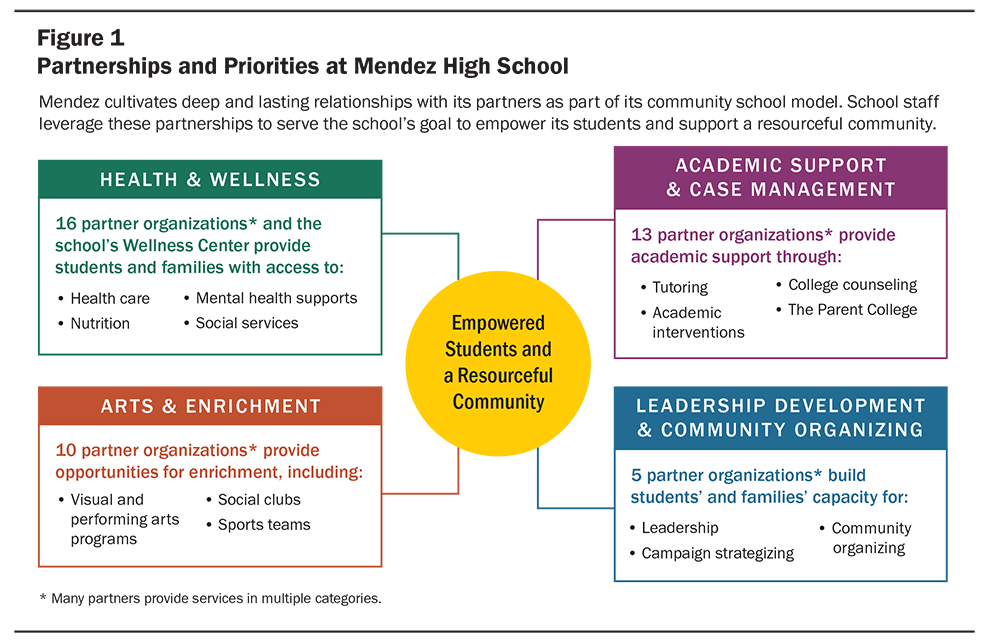

Mendez staff understand that it takes a village to support their students and families with the broad array of opportunities and services that can mitigate the impact of systemic disinvestment in low-income and immigrant communities. In this case, the village—organized in the form of a community school—comprises more than 30 community partners (see Figure 1). Emily Grijalva, the school’s Community School and Restorative Justice Coordinator, explained, “We knew very quickly from when the school opened 10 years ago that schools can’t do it all.… We made sure to immediately connect with a lot of community organizations.”

Mendez partners provide an impressive set of integrated student supports that offer students and their families the health care, nutrition, mental health supports, social services, and learning opportunities that help them to be successful. The school prioritizes the following categories for these supports: academic support and case management, health and wellness, arts and enrichment, and leadership development and community organizing. For example, St. John’s Mobile Clinic is on campus once a week to provide medical services; Self-Help Graphics provides arts enrichment through classes in graphic design; and Impacto “Beyond the Bell” supports after-school clubs on a wide range of interests—from Southeast Asian culture to fashion design. Many of the organizations are longtime partners who are eager to step up to support the students and the school community in whatever capacity they are needed, whether that means providing an annual physical checkup or starting a K-pop club.

Annual assessments of student, family, and staff needs inform these partnerships, which Grijalva coordinates and supports in her role as community school coordinator. Regular communication with partners, including through monthly Coordination of Services Team meetings, ensures alignment and avoids duplication of services. At the monthly meetings, staff from each of the participating organizations (many of whom function as case workers) identify students in need of support, provide updates on how students are doing academically or social-emotionally, and ensure that they are not duplicating resources. Between the monthly meetings, partners conduct phone calls, send emails, and update a shared spreadsheet that tracks the services being provided to students and families.

To maximize partnerships and ensure a good fit, Mendez has three essential agreements that govern its interactions with partners. First, they must be aligned to the school’s vision, including building a community that places students and their needs at the center and shares accountability for student success. Second, partners must share a commitment to meeting the needs of students, their families, and the community, as identified through annual needs assessments. Third, partners must agree to consistent communication to cultivate strong relationships and structures that sustain the work. In the past, staff and leadership have turned down or terminated partnerships that were not aligned to these agreements.

Four community partners provide foundational support: InnerCity Struggle, Promesa Boyle Heights, the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools, and Communities In Schools of Los Angeles (CISLA). Each plays a unique and strategic role in living out the mission and vision for the community school (see “Foundational Partnerships”).

The Partnership for Los Angeles Schools builds capacity of the adults on campus through instructional coaching and Parent College. Promesa Boyle Heights serves as a connector for the neighborhood’s many community organizations and coordinates much of the after-school programming. InnerCity Struggle supports students and families in developing leadership and organizing skills that can advance systemic change in the district and the city to address structural inequities and racial injustice. CISLA provides a dedicated social worker who supports 50 students and their families with case management and also provides whole-school social-emotional and academic services. Additional partners provide services in one or more of the following categories, which are informed by the school’s priorities: academic support and case management, health and wellness, arts and enrichment, and leadership development and community organizing (see Figure 1).

Partnerships are reciprocal at Mendez. Principal Bautista emphasized that staff “see the community and the school as one. What happens in the school impacts the community, and what happens in the community impacts the school.”

Partners are invited to attend school events, like family breakfasts, academic celebrations, or mariachi concerts, and Mendez staff volunteer their time at partners’ events. During a recent reorganization of school space, school staff had to move some community partners out of their office spaces. Several school leaders opted to work in public spaces, such as the school library, and give their offices to partners instead. This flexibility underscores the spirit of pitching in for the good of the community that is central to the Mendez approach.

Foundational Partnerships

The four foundational partner organizations that, along with Mendez’s community school coordinator, anchor the school’s work are InnerCity Struggle, Promesa Boyle Heights, the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools, and Communities In Schools of Los Angeles (CISLA). Staff at these organizations attend monthly Coordination of Services Team meetings facilitated by the community school coordinator, and some played pivotal roles in the founding of the school and continue to extend the operational capacity of its staff.

InnerCity Struggle has deep ties to the broader neighborhood. The 27-year-old community organization has been a fixture in the Eastside of Los Angeles since the Schools Not Jails youth movement in the 1990s and ran the campaign that led to Mendez’s founding. Today, its core role is to develop the leadership of students and families both on and beyond the school’s campus. On campus, InnerCity Struggle develops Mendez students’ leadership and organizing skills through its United Students club, where members identify issues to research and address. United Students also provides academic supports to its student leaders. In the community, InnerCity Struggle employs a multigenerational organizing model to effect systemic change and trains families and community members in community organizing and campaign strategy. InnerCity Struggle was one of the lead organizations in the successful campaign to secure the construction of a comprehensive wellness center on campus. Construction began in December 2019, and the center is expected to open in fall 2021.

Promesa Boyle Heights is a collective of local residents, schools, and community organizations that was established in 2011. It grew out of a combination of a Promise Neighborhoods planning grant and the neighborhood’s Building Healthy Communities Collaborative.The Promise Neighborhoods Initiative, established by the U.S. Department of Education, began with its first cohort of schools in 2010. It is both a grant program funded and managed through the U.S. Department of Education and a place-based strategy for community and school improvement through which “all children and youth growing up in Promise Neighborhoods have access to great schools and strong systems of family and community support that will prepare them to attain an excellent education and successfully transition to college and a career.” When Promesa Boyle Heights and other anchor organizations applied in the program’s first year, they received a planning grant that allowed them to fund a community-engaged plan for this work in their neighborhood, including strategic educational investments in Mendez and other neighborhood schools. Although they were ultimately unsuccessful in obtaining the full Promise Neighborhood grant, they used the vision mapped out in their planning process to pursue private and public funding that could make that vision a reality. Five organizations anchor its work: Proyecto Pastoral, InnerCity Struggle, Boyle Heights Learning Collaborative, Union de Vecinos, and Dolores Mission. Although they were unsuccessful in obtaining the full Promise Neighborhoods grant, the partners did not give up. Promesa Boyle Heights and its anchor organizations decided to move forward with their vision of cradle-to-career supports for the Boyle Heights community by raising an alternate mix of private and public funding.

Promesa Boyle Heights provides Mendez with a number of on-campus resources, including tutoring and academic case management and schoolwide extracurricular and cocurricular opportunities targeted toward youth wellness and development. Promesa Boyle Heights also coordinates the promotoras program, through which community members learn health advocacy skills and become liaisons between service providers and the broader Boyle Heights community. For several years, a Promesa staff member and Mendez administrators anchored and coordinated Mendez’s community partners before the school received district funding for a school-based community school coordinator position.

The Partnership for Los Angeles Schools provides capacity-building support for the adults on campus, namely parents and staff. Through an agreement with the Los Angeles Unified School District, the Partnership manages Mendez and 18 schools in Boyle Heights, South Los Angeles, and Watts. This includes leadership support with strategic planning, budgeting, facilities management, capacity-building, and other core operations. Unlike most of the other schools in the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools network, Mendez joined the Partnership as a brand-new school.

The Partnership focuses on building the capacity of the adults on campus through professional learning communities, targeted instructional supports, and operational supports. Cohort-based coaching and half- or full-day intensive retreats and site visits build the capacity of senior leaders and teacher leaders to be instructional leaders who can manage logistics and ground their decisions in data.Partnership for Los Angeles Schools. (2019). Great leaders, great schools: A closer look at the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools’ model of support for school administrators. (accessed 06/11/21). Each year, the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools and Mendez staff identify a call to action based on a needs assessment and analysis of data. This call to action helps school staff to prioritize resources and partnerships that reflect community need and student interest. The Partnership supports schools in navigating operational challenges, maximizing school budgets, and hiring effective leadership. It also provides the support for Mendez’s Parent Center and puts on the Parent College program, spaces where families can learn skills to support students academically and to become community advocates.

CISLA delivers individual case management provided by a licensed social worker who identifies the services and supports students and families need to be successful. Although CISLA broadly categorizes itself as a dropout prevention and academic engagement program, its social workers deliver a variety of supports, depending on the needs that they identify during their one-on-one check-ins with students and their families. These can include, for example, counseling services, homework help, or referrals to doctors and dentists.

CISLA has also organized whole-school events to support student engagement. For example, several years ago, CISLA staff began conducting one-on-one meetings with 9th-graders on their caseload at the 15-week mark to identify those who were struggling academically. Staff from CISLA and Mendez identified that this intervention would be helpful for all 9th-graders, especially if done more frequently. Now, every Mendez 9th-grader reflects on their report card with a staff or community member three times a year, first at the beginning of school, then at the 15-week mark, and finally in the spring. Although it takes several days to complete the meetings, students, families, and partners have found it to be incredibly valuable in identifying students’ needs early on and connecting them with the appropriate resources.

Academics: High Expectations and Comprehensive Supports

Mendez educators take a whole child approach to teaching and learning. They understand that students are successful when educators treat their lived experiences and their culture as assets in the classroom, provide them with the opportunity to learn, and marry high academic expectations with tailored supports.Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Learning Policy Institute. Hammond, Z. (2015). Culturally Responsive Teaching & The Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Corwin.

Mendez teachers integrate social justice and culturally sustaining practices into their curricula and are well trained and supported in doing so. Bautista encourages staff to bring their knowledge, cultural heritage, and perspective into the classroom, and teachers invite their students to do the same. For example, students write essays on the impacts of gentrification, learn about the Chicano Movement of the 1960s, and analyze plays about the experience of Japanese Americans in internment camps during World War II (Boyle Heights was once home to one of the largest Japanese communities in Los Angeles). They learn about relevant social issues, and their passions fuel engagement and academic success.

As Mendez alumna Arianna Romero reflected, “[Mendez students] are learning … really learning about the community and voting and how to be active in our community, whether it be promoting, advocating, [or] protesting…. We apply that to our school and to our everyday lives.”

A relevant and engaging curriculum provides a foundation for the school’s college-going culture, which includes free and widely available resources to navigate the college-admission process, as well as schoolwide initiatives that ensure that rigorous courses and college-preparatory curriculum are available to all students. The school’s two signature equity initiatives—Computer Science for All and AP for All—expand access to challenging curriculum and prepare students for college and well-paying careers.

Bautista ties the work to expand course access back to the school’s deep commitment to addressing inequities and advancing social and racial justice. “Two groups who are often left out of access to computer science education … are women and students of color,” Bautista shared. “And research shows that many times it’s students of color who are denied access to the more rigorous classes, which include AP classes.… When students of color are given the opportunity to take these AP classes, they tend to do very well.” Under the Computer Science for All initiative, which is enacted in partnership with the University of California Los Angeles Computer Science Equity Project, each student takes an Introduction to Computer Science course and has access to higher-level computer science courses, including game design and AP Computer Science. The AP for All initiative requires that all students, including those with special needs, take at least one AP course during their high school careers, and it provides supports for them to tackle this challenge. This often sets students on a trajectory to take multiple AP courses.

Mendez pairs course access with the tailored supports students need to meet these academic challenges. Employees of City Year, a nonprofit partner, serve as tutors and attend all 9th-grade classes and take notes in order to better support the students with whom they work. Students can meet with a City Year tutor to compare notes, check their understanding of a topic covered in class, and get homework help. Several of Mendez’s after-school programs provide enrichment that is aligned to the curriculum, such as the school’s robotics club.

Mendez also has a very active college center. Senior Eduardo Ruiz said he has “never seen such passion” as he did from the school’s college counselor, Rosa Flores. “She connected us to an organization called Puente Learning Center, which gave us information on the college application process.” From learning about financial aid to the differences between the University of California and community college systems, Ruiz said, “They made it so clear and easy.” These types of supports have helped Ruiz and many of his peers to gain admission to competitive 4-year institutions.

This combination of equity initiatives and thoughtful supports has yielded impressive results. The percentage of Mendez students taking an AP test more than doubled from the 2015–16 school year to the 2018–19 school year, from 118 to 244 students. The number of students receiving a passing score of 3 or higher on an AP test increased from 44 students to 138 during the same period, a jump of over 300%.California Department of Education. (n.d.). Postsecondary preparation data files, AP report 2015–2016, AP report 2016–2017, AP report 2018–2019. (accessed 01/20/21). Romero reflected on how the AP for All initiative impacted her high school experience, saying, “AP classes were scary at first, but once you get the hang of managing two to three AP classes, you’re pretty much ready for college.” While at Mendez, Romero took 3 years of Mandarin and 1 year of AP Chinese Language and Culture in 12th grade, which provided her with the opportunity to travel to Taiwan and learn about the language and culture firsthand.

The Computer Science for All initiative is proving effective as well. At least two graduates of the 2020 class were accepted to universities as computer science majors. Having even two graduates participate in rigorous postsecondary computer science programs is significant for Mendez staff, who see the program as a gateway to high-paying and rewarding careers in science, technology, engineering, and math fields. As more students graduate from this program, Mendez educators are optimistic that the number of alumni participating in postsecondary computer science programs will grow.

Although planning for these initiatives started in 2014, the classes of 2021 and 2022 are the first to graduate as part of the Computer Science and AP for All initiatives, respectively.

To staff and scale these initiatives, Bautista engaged in multiple years of strategic planning and hiring. He listened to staff concerns and shared research on the positive impacts of access to computer science instruction to build staff support for the Computer Science for All initiative, which necessitated hiring additional math teachers and training them to teach computer science. “The rest of the school had to be on board, because the math department became our biggest department,” Bautista explained. “[Even when] there were [openings] to hire in other departments, the rest of the team had to be on board that it was going to be another math hire” in order to ensure there were enough teachers to staff the initiative.

Bautista described recruiting and retaining quality teachers as “one of the highest leverage points for the success of our school.” He received his teacher and principal training at the UCLA School of Education, which focuses on preparing social justice educators to teach in an urban setting. He invites candidates from the program to observe classes and do their student teaching at Mendez and often makes job offers to promising candidates before they have finished their preparation. An aligned vision and strong and supportive leadership are two of the core reasons Mendez had no turnover of staff from 2017 to 2020.

The school’s academic programming, supported by its high-quality teachers, makes it comparable to competitive programs throughout the district. Zahara Green, parent of one current student and two graduates and director of the Parent Center, tells the story of moving her daughters to a district magnet school, which the family thought was a more rigorous academic option. Upon arrival, she quickly discovered that the young women had already taken the classes offered at their grade level in their previous years at Mendez. After 3 hours at the new school, Green brought her daughters back to Mendez, where she knew they would have both rigorous academic opportunities and a welcoming and supportive community. And she is not alone. Many families send multiple students to Mendez, and more than 20 of the school’s staff are or have been Mendez parents, including Bautista.

School Climate: A Welcoming Culture Starts With Family

Mendez educators, partners, students, and families cultivate a safe, tight-knit school community. The Mendez staff, students, and families interviewed all spoke to a strong school culture in which members of the community feel welcome and supported. Staff member Grijalva said Mendez reminds her of her “small town in Guatemala.” For parent Zahara Green, becoming parent liaison was an easy transition because staff “were already family.” And for alumna Romero, Mendez felt like “a second home” because of the support students felt in bringing their culture and full selves to school. In 2019, 85% of students reported feeling safe at Mendez.Los Angeles Unified School District. (2019). LAUSD School Experience Survey results 2018–19. (accessed 04/02/21). The science of learning and development identifies the link between students feeling safe and supported at school and their ability to learn.Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Learning Policy Institute.

Mendez prioritizes small classes that support students in developing relationships with their teachers and with one another. When it comes to making decisions about class size, Bautista thinks like a Mendez parent, which he is.

I always ask people, … “Would you rather send your kid to a school with 41 students per class, or would you rather send your kids to a school with 27 students per class?” And I have not yet heard one single person say that they would rather send their own kids to a school with 41 students per class.

Small class sizes can allow students to know and be known by their teachers, which can create a system of social, emotional, and academic support.Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Learning Policy Institute. Trusting relationships with teachers and with school staff create an environment in which students are comfortable voicing their needs and concerns—academic or otherwise—confident they will be heard. Romero experienced this during her time at Mendez: “It’s not just you go to school and go home. [Teachers and administrators] care about you everywhere and [care about] your general well-being.”

Building a culture of belonging extends to the clubs and extracurricular options available on campus, and the school is often open evenings and weekends to support the many activities it offers. Despite its relatively small size, Mendez boasts over 45 clubs and teams. The mentality of the staff is largely that if students are interested, the adults will find a way to make it happen. Bautista explained that part of the school’s vision is “being able to provide the students opportunities to connect with the school at multiple levels.” He emphasized that “extracurricular activities, athletic programs, and visual performing arts programs are all vital so students feel connected and safe at the school.”

Grijalva, the Community School and Restorative Justice Coordinator, shared that this spirit is one of her favorite aspects of Mendez: “If a student has an idea and they can get a teacher sponsor and a group of students together, we’ll form that club [or activity]…. We don’t have a swimming pool, and yet we have a swim team.”

Mendez staff put in an equal amount of effort to ensure that families also feel safe, included, and welcome on campus. For Green, Mendez initially felt like any other school. That changed after her son Zalen passed away and Bautista and several teachers visited her home to personally offer their condolences. “They could have just sent a note, but they didn’t.... They showed us that they were there for us,” Green said, expressing that the caring attention of staff members when her child died “made them family. It’s been that way ever since.”

Green now manages the Mendez Parent Center, which is a hub for families on campus. There, parents and community members can take and teach classes on their interests, sign up to volunteer at the school, and connect with members of the Mendez community.

Mendez’s robust parent programming provides ample opportunities for families to engage with the school. To foster a love of literacy among parents, which was identified as a goal during a recent needs assessment, Grijalva leads a book club. In fall 2020, they read Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye in Spanish. The school also hosts regular Zumba classes, trains parents as promotoras (health advocates), and provides opportunities for parents to teach and learn manualidades (crafts). These options open the campus up to parents in a variety of capacities, from volunteering in classrooms to full leadership positions, which helps Mendez deliver on its original goal of being a community hub.

Boyle Heights neighbors are equally part of the Mendez community. The new Mendez Wellness Center, which is expected to open in December 2021, will be available to all residents in the neighborhood. In 2013, InnerCity Struggle campaigned for a $50 million allocation from the district to build wellness centers in the highest-need schools, including Mendez. The Mendez Wellness Center received $8.5 million of that funding. The recommendation to build the center on the Mendez campus was made after significant campaigning, in the interest of providing both broad and targeted health access to the whole community. The district’s original plan was to build the health center on the neighborhood elementary school campus. This location, however, would have limited its hours of accessibility, making it more challenging for members of the community to use. The initial needs assessment also identified that a high priority for the health center was access for young men to its services. Locating the health center on the elementary school campus might have disincentivized them from using it. Community organizers were successful in pushing instead for the wellness center to be located on the Mendez campus.

The school’s focus on wellness and mental health extends to Mendez staff. Administrators model social-emotional wellness and practice setting reasonable boundaries in order to encourage staff to do the same. Administrators discuss social-emotional health and are open about taking sick days to care for themselves and their families. Grijalva explained that these practices allow her and other teachers to “know that it’s OK if [their] child’s sick and [they] have to take that day off,” which helps relieve some pressure and avoid burnout. She is not the only staff member who experiences a sense of safety, support, and community at Mendez. On the district’s school experience survey, 95% of staff reported that they felt safe at the school and described the overall school climate among staff as positive.Los Angeles Unified School District. (2021). LAUSD School Experience Survey results 2020–21. (accessed 07/02/21).

Bautista also combats burnout and turnover by ensuring that staff have a voice in making school decisions. For example, each year he shares the proposed master schedule with staff and meets with each teacher to discuss their assignment for the following year and receive their feedback before confirming the schedule with the district. Although it may take more time to listen to staff perspectives than to move ahead without their input, this and practices like it can create a culture in which staff are supported and included and are co-creators of a shared vision for the school.

Leadership: “We Are in It Together”

To honor the legacy of Felicitas and Gonzalo Mendez, and as part of the school’s commitment to the community school design, school leaders practice a model of shared power and distributed leadership. For students, this translates into opportunities to make real change on campus. Such was the case when students from InnerCity Struggle’s United Students club successfully campaigned to extend lunchtime to ensure fewer students go hungry and less food is wasted—a move that required changes to the master schedule. For staff, it means exploring, developing, and leading initiatives. The school’s signature equity initiatives and its restorative justice program, for example, were all proposed by staff during Local School Leadership Committee and department meetings. For families and community partners, it includes grassroots organizing training through InnerCity Struggle, the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools, and Promesa Boyle Heights. Claudia Martinez-Fritzges, of the Partnership for Los Angeles Schools, noted, “At Mendez, there is this ‘We are in it together, we have to solve it together’ [attitude].”

Student leadership development is central to the school’s mission, and Mendez staff encourage students to flex their leadership muscles, even when they challenge existing practices. For example, staff proudly shared an example of the Gender Sexuality Alliance club members pushing for more diverse representation in the school’s curriculum during humanities department team meetings. Since Mendez’s founding, students have had access to InnerCity Struggle’s United Students club, which develops their leadership and organizing skills. Another local nonprofit organization, Las Fotos Project, teaches young women photography and leadership skills, as well as how the medium can be used for social change. Las Fotos Project also provides opportunities for Mendez students to showcase their work.

The leadership skills that students develop at Mendez can support continued advocacy work and engaged citizenship after high school. Romero is currently a sophomore at UC Irvine and is majoring in political science. She recalled that in her sophomore year at Mendez, she “really learned how to bring [her] activism work into school,” by writing on issues that she cared about for her English class, like gentrification and the Dakota Access Pipeline. Romero has already seen her many Mendez experiences—including her leadership work with United Students and Las Fotos Project—serve her in higher education. She said, “I don’t think I would be here without Mendez teaching me and showing me … what I can do. I don’t really know what I’m going to end up doing after graduation, but I know that I want to be an advocate for my community.”

Administrators also cultivate staff leadership and encourage new ideas. Grijalva began her career at Mendez teaching English but developed an interest in restorative justice and proposed a pilot project at Mendez. She recalled that Bautista said he was “still iffy about restorative justice,” but that he invited her “to challenge [him].” According to Grijalva, after she had worked for couple of years on a restorative justice program that had started as a “side project,” Bautista recognized that the initiative bolstered a positive school climate. He created the restorative justice coordinator position so that staff could continue growing this work at Mendez. The role contributes to both Grijalva’s professional growth and the strong, positive community among students and staff.

Families also have opportunities to engage in leadership roles. Mendez has multiple governing bodies with opportunities for shared leadership. In addition to a school site council, which is standard at schools across the state, Mendez has a Local School Leadership Committee, a School Culture Committee, a Family Action Team, and a House of Student Representatives. Bautista participates in the various decisions that these governing bodies weigh in on, ensuring that they can collaboratively make decisions for the school on important issues like budgeting, scheduling, or professional development. By creating space for leadership at multiple levels of the school community, administrators strengthen decisions and ensure that they reflect the needs and interests of the broad school community.

Building the leadership capacity of families and the community has also benefited Mendez. This has been especially visible with the 10-year campaign to bring a wellness center, funded by the district, to the Mendez campus. Promesa Boyle Heights staff, InnerCity Struggle organizers, and Mendez families led the campaign, which included surveying members of the community and identifying a high need for the neighborhood’s young men to be provided with health services. The school broke ground on the 6,500-square-foot building in December 2019.

A Product of Boyle Heights

No two community schools are alike, because no two communities have the same needs and assets, hopes and dreams for their students. Mendez High School demonstrates the power of a community school model to foster deep connections among students, families, staff, and partners. The school recruits and retains high-quality educators who are part of the community, who hold high expectations for students, and who deliver necessary supports. Mendez leaders share ownership of the school with other members of the community and actively empower students, staff, and families through distributed leadership. Together, these structures and practices are changing the life trajectories of young people in Los Angeles’s Eastside.

Key Learnings From Mendez High School

- Relationships undergird every aspect of life at Mendez and are a priority among staff. Healthy, strong relationships are key to Mendez’s success, from its foundational partnerships to the open collaboration between staff, families, students, and the broader community.

- Academic opportunity—which offers rigor with cultural relevance and strong supports—is a social justice issue. Central to Mendez’s commitment to education equity is ensuring that academic opportunity extends beyond the number of rigorous courses that students have access to; it also includes making sure that students have adequate supports to succeed at those rigorous courses and that their culture and identity are reflected in the curriculum.

- Partnerships are strategic, and staff use intentional structures to support them. Consistent needs assessments ensure that partnerships are relevant and aligned to a shared mission and set of goals. This helps to set expectations and build trust among the many stakeholders in the Mendez community, which supports fruitful partnerships.

- Recruiting high-quality educators and supporting their professional growth contributes to academic gains and high retention rates among staff. Mendez leaders prioritize recruiting and retaining high-quality educators who are committed to the school community. Trusting teachers’ expertise, supporting their growth, and creating space for work-life balance helped Mendez retain all of its teachers from 2017 to 2020.

- Leadership is a collective endeavor. School leaders see staff, families, and students as equal partners in student and school success, and community-based organizing is encouraged as a strategy for making lasting change. The school’s commitment to shared leadership helps strengthen the collective power of the community, which benefits Mendez students.

- Community organizing efforts can support the authenticity of the work and increase capacity. At Mendez, community organizations have played a key role in the school’s founding and its continued grounding in the goals and needs of the community. These organizations have also increased the capacity of the staff by providing for or securing resources and taking on key responsibilities.

"A Line in Time": Responding to COVID-19

The community school infrastructure that serves Mendez students and families during “typical” times enabled Mendez staff and partners to respond quickly and thoughtfully when schools closed in Los Angeles and around the country due to the spread of COVID-19. Principal Bautista calls March 13, 2020—the day the schools closed—“a line in time” that changed everything for Mendez students, staff, and families.

Coordination of Services teams already met monthly to track student engagement and coordinate service delivery. These were transitioned to weekly virtual meetings. When families were unreachable by phone call or text, staff and partners leveraged their extensive existing relationships to conduct socially distanced home visits and deliver resources such as personal devices or food items.

Community partners jumped at the opportunity to support the school. The St. John’s Mobile Clinic, on campus 1 day a week before and during the pandemic, began COVID-19 testing for the community. Promesa Boyle Heights and InnerCity Struggle conducted regular mental health check-ins with students via phone or device (and sometimes at a safe physical distance in person). CISLA texted and called students and created care packages with food, toilet paper, EBT cards, or whatever families needed. Teachers organized to get Wi-Fi hot spots to families before the district had the capacity to do so.

Over the summer, Mendez administrators created opportunities for families, staff, and students to connect, reflect, and think together about how to plan for the coming year. Staff members surveyed students and found that the six-course schedule in the semester system was overwhelming to students, many of whom were dealing with additional stress brought on by the pandemic. The Local School Leadership Committee and its scheduling subcommittee proposed switching to a quarter system in the fall that would give students and teachers fewer concurrent classes to manage and provide more opportunities to ensure students received the supports that would help them to be successful.

Importantly, staff also decided to start the 2020–21 school year in a virtual setting, and the school paid teachers to use the summer for additional training on different virtual platforms and curricula to improve their ability to teach remotely. Because Mendez began its planning early and engaged the community, there was a groundswell of support for the schedule. This allowed Mendez to apply for a waiver from the district to run this community-determined schedule in the fall.

Through their outreach to families, Mendez staff learned that Wi-Fi was not the only barrier to virtual learning: Often siblings were sharing a single device, and some did not have access to desks or chairs. In response, each student was allowed to bring home a personal device with digital subscriptions to textbooks and platforms, and to borrow furniture from the school.

The school and its partners continued to promote a positive (virtual) school culture through extracurricular opportunities. Many of the student clubs still met virtually. Community partners scaled back their meetings to a biweekly schedule and used this meeting time to track student engagement and service delivery. The Parent Center ran programming at or after 6 p.m. so that parents and students did not have to compete for limited devices and so that students could be on hand for tech support.

As the community navigates returning to campus, staff and partners are prioritizing the needs of students, families, and the community. The community school structures that have been in place since Mendez’s founding will continue to anchor the work and support staff in delivering on the original vision of the school as a community hub that enacts racial and educational justice in Boyle Heights.

Felicitas & Gonzalo Mendez High School: A Community School That Honors Its Neighborhood’s Legacy of Educational Justice (research brief) by Charlie Thompson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Funding for this project was provided by the California Community Foundation, Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Sobrato Philanthropies, and Stuart Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, and Sandler Foundation. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.