Sharpening the Divide: How California’s Teacher Shortages Expand Inequality

Summary

Teacher shortages that most severely affect schools serving the least advantaged children have been part of the California education landscape for the last half decade. This brief describes how key teacher supply and demand factors vary across the state, and it provides potential policy solutions to mitigate ongoing shortages. The brief also offers insight into how the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to impact teacher supply, demand, shortages, and diversity.

This brief is drawn from the report Sharpening the Divide: How California’s Teacher Shortages Expand Inequality and is accompanied by an online interactive map of district- and county-level teacher supply and demand factors.

When California students returned to school in fall 2019, hundreds of thousands returned to classrooms staffed by substitutes and teachers who were not fully certified. According to one news story, “More than three weeks into the school year, several hundred Sacramento City Unified School District students are being taught by substitutes as school officials continue to look for teachers to staff classrooms.”Morrar, S. (2019, September 18). Sacramento City Unified teacher vacancies mean hundreds of students are taught by substitutes. Sacramento Bee. (accessed 10/18/19). In 2020, the prospect of starting school in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic made the problem of teacher shortages all the more worrisome. Before the start of the school year, Katie McNamara, Superintendent of the South Bay Union School District in Southern California, told the California State Assembly Education Committee, “The level of difficulty in opening school is very high. [It] feels close to impossible without more staff.”Public comment to California State Assembly Education Committee (06/16/20). (accessed 10/16/2020) Many wonder whether California schools will have the teachers they need to weather this crisis. Will teachers flee the profession or retire early due to fears of returning to in-person teaching in the midst of the pandemic? Will districts lay off teachers due to budget cuts, or will they need to hire more teachers to meet social distancing requirements? Most likely, district experiences will vary based, in part, on the characteristics of their teacher workforces and their financial outlooks. However, recent history suggests that long-standing shortages in high-need fields and schools are likely to persist. California has taken a proactive approach to addressing shortages in recent years, and now is an even more critical time to see those efforts through.

This brief describes how key teacher supply and demand factors vary across the state and offers potential policy solutions to mitigate ongoing shortages. It also offers insight into how the COVID-19 pandemic is likely to impact teacher supply, demand, shortages, and diversity.

This analysis is the fifth installment in a series of Learning Policy Institute reports that document the status of the TK–12 teacher workforce. It draws on the most recent publicly available data from the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) and public and restricted-use student and staffing data from the California Department of Education (CDE).

Key Findings

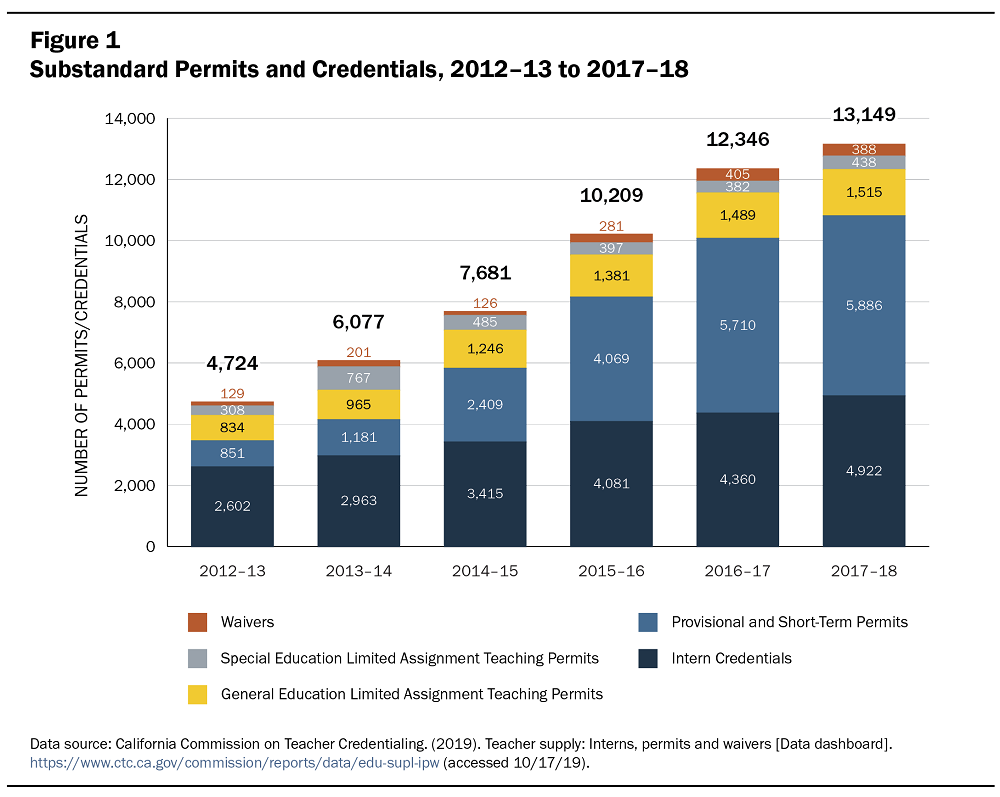

- Teacher shortages have continued to grow in California, especially in high-need subjects (such as special education, mathematics, science, and bilingual education) and in high-need schools. Emergency-style permits have increased sevenfold since 2012–13.

- Shortages lead to the hiring of teachers without preparation and disproportionately impact districts serving concentrations of students from low-income families. These districts also disproportionately hire beginning teachers who turn over at higher rates. These conditions create opportunity gaps that exacerbate achievement gaps.

- Though a growing body of research shows that being taught by teachers of color is associated with academic benefits for students of color, there are wide differences in students’ access to teachers of color across districts, with 9% of districts having no teachers of color and 58% having less than 20%.

- Shortages are driven by three major factors: (1) the decline in enrollment in teacher preparation programs; (2) increased demand for teachers; and, especially, (3) teacher attrition and turnover.

- The impact of COVID-19 on the teacher workforce is still unfolding: Early evidence suggests that shortages are likely to continue and may worsen with expected teacher retirements and resignations as well as a shrinking pipeline. California’s investments in addressing teacher shortages—funding support for new undergraduate teacher preparation programs, teacher residencies, and teacher preparation for classified staff, for example—are starting to yield modest results; however, these were one-time investments, and long-standing structural shortages of qualified teachers in high-need fields and schools are likely to continue to require systemic and ongoing policy attention.

Is There Still a Teacher Shortage in California?

One of the best indicators of teacher shortages is the prevalence of substandard credentials or permits, which by law should be issued only when fully credentialed teachers are not available.Full credentials include (1) preliminary credentials, awarded to individuals who successfully complete a CTC-approved teacher preparation program and the state assessments required, and (2) clear credentials, awarded to preliminary credential holders upon successful completion of an induction program. Preliminary credentials are valid for 5 years and clear credentials are renewable every 5 years. Substandard credentials and permits include (1) provisional internship permits (PIPs), short-term staff permits (STSPs), and waivers, which are 1-year emergency-style permits used to fill immediate and acute staffing needs with individuals who have not completed teacher preparation programs or demonstrated subject-matter competence to teach a particular grade, course, or student population; (2) limited assignment teaching permits, which allow fully credentialed teachers to teach outside of their subject area to fill a staffing vacancy or need; and (3) intern credentials, which are awarded to teachers in training who have demonstrated subject-matter competence but have not completed a teacher preparation program or met the performance assessment requirements for a full license. California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (n.d.). Data terms glossary. In 2017–18, California issued more than 13,000 substandard credentials and permits (i.e., intern credentials, permits, and waivers), nearly triple the number issued in 2012–13 (see Figure 1). Further, the fastest-growing types of substandard authorizations are provisional and short-term permits. These emergency-style permits—issued to individuals who have not demonstrated subject-matter competence for the courses they teach and who often have not entered a teacher training program—have increased sevenfold since 2012–13. The growing number of substandard credentials issued by the state is an indicator that teacher supply continues to be insufficient to meet the demand for those positions.

Teachers on substandard credentials and permits are not equally distributed across the state. Statewide, about one in three teachers who were new to their district in 2017–18 were teachers on substandard credentials. However, some districts (roughly 15%) did not hire any teachers on substandard credentials in 2017–18, while in other districts, more than half of new hires had substandard credentials. Those districts that hired the most teachers on substandard credentials also had many more students from low-income families compared to districts with none of these hires (72% of students from low-income families vs. 52%). In other words, districts with more students from low-income families disproportionately hire teachers on substandard credentials and permits. Thus, it is likely that any worsening of teacher shortages related to COVID-19 will disproportionately impact students from low-income families.

While the still-unfolding pandemic and the move to distance learning have caused uncertainties about the status of the teacher workforce, a number of factors suggest that teacher shortages are likely to worsen. Recent polls across the country, for example, indicate that as many as 20% to 30% of teachers were considering resigning or retiring as a result of the pandemic.Page, S. (2020, May 27). Back to school? 1 in 5 teachers are unlikely to return to reopened classrooms this fall, poll says. USA Today. (accessed 08/01/20); French, R. (2020, June 4). Nearly a third of Michigan educators mull quitting because of coronavirus. Bridge Michigan. (accessed 07/24/20). In addition, the already limited pool of new teacher candidates is shrinking as enrollment in teacher preparation programs has declined.Kini, T. (2020, June 25). Raising demands and reducing capacity: COVID-19 and the educator workforce [Blog post]. Physical distancing guidelines may further increase teacher demand in districts that require more staff once schools reopen in person.

The shortage of fully prepared teachers in affected schools has consequences for student learning. Prior research finds teachers who have received little preservice preparation are less effective than fully prepared teachers, and they leave at two to three times the rate of teachers who have been well prepared.Podolsky, A., Darling-Hammond, L., Doss, C., & Reardon, S. (2019). California’s positive outliers: Districts beating the odds. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Ingersoll, R., Merrill, L., & May, H. (2014). What are the effects of teacher education and preparation on beginning teacher attrition? Philadelphia, PA: Consortium for Policy Research in Education, University of Pennsylvania. A recent study of California districts in which students outperformed their peers statewide found that, overall, these districts employed fewer teachers on substandard credentials and permits than the state average.Burns, D., Darling-Hammond, L., & Scott, C. (with Allbright, T., Carver-Thomas, D., Daramola, E. J., David, J. L., Hernández, L. E., Kennedy, K. E., Marsh, J. A., Moore, C. A., Podolsky, A., Shields, P. M., & Talbert, J. E.). (2019). Closing the opportunity gap: How positive outlier districts in California are pursuing equitable access to deeper learning. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. After controlling for several school and community characteristics, these lower rates of hiring teachers on substandard credentials were associated with significant increases in student academic performance, especially for African American and Latino/a students.Podolsky, A., Darling-Hammond, L., Doss, C., & Reardon, S. (2019). California’s positive outliers: Districts beating the odds. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

What Is Causing California’s Teacher Shortages?

Analysis of statewide teacher supply and demand factors indicates that there are three main factors driving shortages in California: (1) the decline in teacher preparation enrollments, (2) increased demand for teachers, and (3) teacher attrition and turnover. However, the relative weight of supply and demand factors can vary from district to district.

The Decline in Teacher Preparation Enrollments

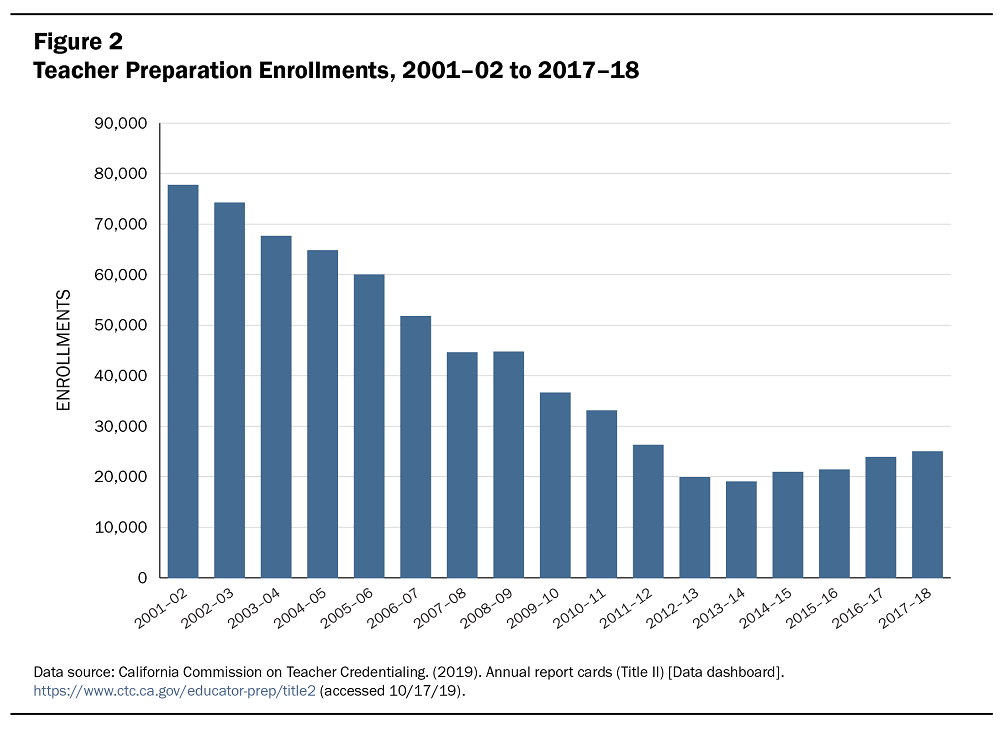

Enrollment in teacher preparation programs in California declined by more than 75% between 2001–02 and 2013–14, from 77,705 to 18,984, respectively. (See Figure 2.) As a result, the number of candidates completing teacher preparation has also declined substantially. From this very low base, the modest increase of about 6,000 enrollments between 2013–14 and 2017–18 still leaves a significant gap between teacher supply and demand. At the current rate of growth in enrollment, it would take at least another 17 years to reach 2001–02 enrollment levels.

The challenges of teaching in the era of COVID-19, and the economic impacts associated with the pandemic, may exacerbate the conditions that have been discouraging enrollment in teacher preparation programs in recent years: layoffs during the Great Recession and uncertainty about district finances to support hiring since the pandemic hit, rising college costs combined with relatively low teaching salaries, and inadequate financial aid.Darling-Hammond, L., Sutcher, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Teacher shortages in California: Status, sources, and potential solutions. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; U.S. Department of Education. (2015). Web tables: Trends in graduate student financing, selected years, 1995–96 to 2011–12 (NCES 2015-026). Washington, DC: Author; Podolsky, A., & Kini, T. (2016). How effective are loan forgiveness and service scholarships for recruiting teachers? [Brief]. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Baum, S., & O’Malley, M. (2003). College on credit: How borrowers perceive their education debt. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 33(3): 7–19.

Increased Demand for Teachers

Each year, districts submit to the state an estimate of the number of teachers they need to hire to fill positions. Between 2013–14 and 2017–18, annual district hiring estimates increased by 43%. Statewide, attrition is by far the greatest driver of demand for new teachers; however, districts may also be hiring teachers to reduce student–teacher ratios or to meet the needs of growing student enrollments. As a result of the Great Recession, state budget cuts from 2008 to 2012 caused teacher layoffs and growing class sizes, so in recent years districts have sought to return to pre-recession staffing levels.

Based on our analysis of CDE student enrollment and staffing data, the state of California would need more than 4,100 additional teachers in order to return to its overall pre-recession student–teacher ratio (21:1). In 2017–18, roughly 60% of districts still had a student–teacher ratio that was larger than their pre-recession levels. These districts, and others, may continue to hire to improve upon their pre-recession student–teacher ratio in pursuit of class sizes more aligned with national standards, which tend to be considerably smaller. In light of COVID-19, some districts may see increased demand for teachers due to increases in teacher turnover. Districts reopening for in-person learning may also need more teachers to accommodate smaller groups and enable physical distancing.

Defining Teacher Attrition and Turnover

In our analysis, teacher attrition refers to leavers, or the rate at which California teachers leave the state’s public school system, whether to retire, change careers, teach in a private school, or teach in another state, for example. Teacher turnover includes leavers and movers: that is, teachers who leave public school teaching in California and those who move to teach in a different district.

Teacher Attrition and Turnover

Teacher attrition and turnover are primary drivers of shortages. Between 2016–17 and 2017–18, 9% of California teachers left teaching in the state’s public school system.Due to the limitations of the data we analyzed, it is not possible to differentiate teachers who leave the teaching profession from those who choose to teach in private schools or to teach outside of California. We are also not able to determine whether teachers have left to retire or for other reasons. This attrition drives nearly all of the demand for teacher hires. According to national estimates, most of this attrition occurs when early- and mid-career teachers leave, often due to dissatisfaction with their positions or with the profession.Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Just one third of attrition is caused by retirements.Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

In addition to the 9% of teachers leaving teaching in the state’s public school system, another 3% move districts, for a total turnover rate of 12%. Even when teachers continue teaching in California schools, turnover can exacerbate shortages and impact student achievement in the districts they leave.Ronfeldt, M., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2013). How teacher turnover harms student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 50(1), 4–36. Prior research suggests that high turnover rates are associated with poor working conditions, lack of teacher preparation, and poor compensation.Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Lack of administrator support, in particular, is a major predictor of turnover, more than doubling turnover rates.Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

District turnover rates span a wide range. On one end of the spectrum, nearly 1 in 10 districts has a turnover rate under 5%, comparable with high-achieving school systems internationally.Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the U.S. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. At the other end of the spectrum, roughly 1 in 10 districts has a turnover rate of 25% or more. Districts with a higher turnover rate also have greater proportions of students from low-income families.

Quick Facts on Teacher Supply and Demand Across California, 2017–18

Teacher Supply:

- New hires (beginning and veteran teachers who are in their first year of service to their district) made up 10% of California’s teacher workforce. About 5% of districts, though, had no new hires in 2017–18, while, in contrast, roughly the same number of districts had 40% or more new hires. Districts with the most new hires serve more students from low-income families and have turnover rates twice as high as districts with average, or below-average, proportions of new hires.

- Beginning teachers—those in their first or second year of teaching—comprise 12% of California’s teacher workforce overall. Roughly 10% of districts employ fewer than 3% beginning teachers, and the majority of those districts had no beginning teachers in 2017–18. Meanwhile, about one in four districts employs 20% or more of these teachers.

- Re-entrants, or California teachers who return to teaching after having left for a period of time, make up about a quarter of new hires in recent years. Nearly 20% of teachers who left after 2015–16 returned to teaching in the state in 2017–18, with about 12% of leavers returning to the same district that they left.

Teacher Demand:

- Teacher attrition accounts for about 90% of the annual demand for new teachers in California. Between 2016–17 and 2017–18, 12% of California teachers either left public school teaching in the state (9%) or moved to another California district (3%). Nearly 1 in 10 districts has a turnover rate under 5%, while another roughly 1 in 10 districts has a turnover rate of 25% or more. Districts with the highest turnover rates also serve more students from low-income families, disproportionately impacting student achievement in those schools.

- Although California is gradually nearing its pre-recession student–teacher ratio of 21:1, the state would need more than 4,100 additional teachers in order to reach that benchmark. In 2017–18, roughly 60% of districts still had a student–teacher ratio that was larger than their pre-recession levels.

- Total student enrollment in the state was essentially unchanged between 2016–17 and 2017–18, but nearly a quarter of districts experienced enrollment increases or decreases of 5% or more.

- California’s teacher age distribution has shifted to include more mid- and late-career teachers and fewer early-career teachers. About 40% of the teacher workforce is age 50 or older, and the 14% of California teachers age 60 and older are likely to retire within the next 5 to 10 years.

Teachers of Color in California Districts

In addition to having a supply of teachers to meet demand, many California districts are interested in providing students with a teacher workforce that reflects the rich racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity of the state and are seeking ways to better recruit and retain teachers of color. A wide body of research shows that being taught by teachers of color is associated with benefits to all students, with students of color, especially Black students, experiencing boosts in academic achievement, graduation rates, and aspirations to attend college, among other benefits.Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Diversifying the teaching profession: How to recruit and retain teachers of color. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

With 34% teachers of color statewide, the proportion of teachers of color in California noticeably exceeds the national average of 20%.Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Diversifying the teaching profession: How to recruit and retain teachers of color. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. Still, people of color comprise more than 60% of California’s total population and about 75% of California’s public school student population.U.S. Census Bureau. (2018). QuickFacts: California. (accessed 11/04/19); California Department of Education. (n.d.). 2018–19 enrollment by ethnicity and grade, state report. (accessed 12/16/19). Across districts, students have inequitable access to racially and ethnically diverse teachers, with 9% of California districts having no teachers identifying as a person of color in 2017–18, and 58% having a proportion less than the national average of 20%. Just 5% of California districts had 60% or more teachers of color. These districts with the most teachers of color are also those serving the most students from low-income families, with nearly 90% of students from low-income families. National research suggests that several factors can depress the supply of teachers of color, including the debt burden of pursuing comprehensive teacher preparation and high turnover rates associated with working in under-resourced schools with poor working conditions.Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Diversifying the teaching profession: How to recruit and retain teachers of color. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic could further depress the supply of teachers of color. The pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on the higher education plans of people of color, with half of Latinos and about 40% of Black and Asian Americans canceling or otherwise changing their plans, including delaying enrollment, reducing courses, or switching institutions.Fain, P. (2020, June 11). Latinos, African Americans most likely to change education plans. Inside Higher Ed.. This is likely to negatively impact efforts to increase the diversity of the teacher workforce.

Policy Considerations

In recent years, California began to take a proactive approach to addressing teacher shortages. Between 2016 and 2019, the state Legislature invested nearly $300 million to build the teacher pipeline and recruit and retain well-prepared teachers. While the largest investments are for programs that have not yet been fully launched, and many of the other investments are for programs that will take a number of years to produce graduates, efforts to rebuild the teaching force are beginning to yield modest results. However, at the current rate of growth in enrollment in teacher preparation programs, it would take at least another 17 years to reach 2001–02 levels. Furthermore, nearly all of these initiatives were funded only on a one-time basis in the state budget.

Given the severity of ongoing shortages and the disproportionate impact of shortages on particular districts, subject areas, and student populations, California may need to go beyond its prior one-time investments and consider further action to address the ongoing need for teachers. Demand from districts and institutions of higher education for the programs the state has invested in is high, with funding insufficient to cover the number of eligible applicants. Furthermore, as the COVID-19 crisis unfolds, long-standing structural shortages of qualified teachers in high-need fields and schools will likely require systemic and ongoing policy attention. A 2020 poll of California voters points to substantial support for addressing these issues.Polikoff, M., Hough, H., Marsh, J., & Plank, D. (2020). Californians and public education: Views from the 2020 PACE/USC Rossier Poll. Stanford, CA: Policy Analysis for California Education. For the second year in a row, reducing the teacher shortage was among the top three most important education issues identified by likely voters. Previous research suggests consideration of the following eight evidence-based approaches for addressing California’s ongoing teacher shortages in ways that will build a stronger, more stable, and more diverse teacher workforce for the long term:

- Maintain and expand high-retention pathways into teaching, such as teacher residencies and Grow-Your-Own (GYO) pathways.

As attrition drives demand for new teachers, policies can expand high-retention pathways into teaching. High-quality teacher residencies, for example, are 1-year intensive apprenticeships that have consistently resulted in higher teacher retention rates. Targeting high-need subjects and locations, residencies have also been found to attract more diverse candidates.Guha, R., Hyler, M. E., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). The teacher residency: An innovative model for preparing teachers. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. GYO programs recruit and train local community members (e.g., paraprofessionals, school staff, high school students) who are more likely to reflect local diversity and are more likely to continue to teach in their communities.Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Espinoza, D., Saunders, R., Kini, T., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2018). Taking the long view: State efforts to solve teacher shortages by strengthening the profession. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute; Carver-Thomas, D. (2018). Diversifying the teaching profession: How to recruit and retain teachers of color. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. California’s Classified School Employee Teacher Credentialing Program, funded at a total of $45 million during 2016 and 2017, offers a strong GYO model on which to build. More than half of candidates in the program are candidates of color.California Commission on Teacher Credentialing. (2019). Update on three state-funded grant programs. Sacramento, CA: Author. (accessed 01/25/20). The state’s Teacher Residency Grant program, funded at $75 million in 2018, is funding 38 residency partnerships between teacher preparation programs and local educational agencies,Local educational agencies include school districts, county offices of education, and some charter schools. which began producing graduates in spring 2020. - Provide service scholarships to all teacher candidates who complete preparation and commit to teach in high-need fields and locations.

Service scholarship and loan forgiveness programs are highly effective recruitment and retention strategies that underwrite the cost of teacher preparation in exchange for a number of years of service in the profession, often in a high-need subject or school.Podolsky, A., & Kini, T. (2016). How effective are loan forgiveness and service scholarships for recruiting teachers? [Brief]. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. The state is due to launch a service scholarship program, the Golden State Teacher Grant Program, which will provide a $20,000 service scholarship to teacher candidates in special education who commit to teach in a high-need school for 4 years after earning their credentials. Continuation of this program will be important so that it can effectively serve as a recruitment and retention incentive for prospective teachers. - Ensure equitable access to mentoring and induction programs for novice teachers.

Evidence suggests that strong mentoring and induction for novice teachers can be a valuable strategy to retain new teachers and improve their effectiveness.Ingersoll, R. M., & Strong, M. (2011). The impact of induction and mentoring programs for beginning teachers: A critical review of the research. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 201–233; Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. All beginning California teachers are required to complete an induction program to earn their clear credential. However, state funding once targeted for induction is now folded into the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF). This has resulted in many districts reducing their support for new teachers, and costs disproportionately fall on districts with high proportions of novice teachers.California Commission Teacher Credentialing. (2015, September). Report on new teacher induction. (accessed 05/04/17). It may be useful to develop creative state strategies to support districts with large numbers of beginning teachers while preserving the local control benefits of the LCFF. - Streamline requirements for entry into the profession by considering multiple pathways for demonstrating competence for both in-state and out-of-state entrants to the profession.

An earlier analysis of teacher shortages in California identified state testing policies as a contributor to shortages, both because of their financial costs to candidates and because of their cumulative fail rates, which substantially reduce the pipeline of teachers. The CTC is currently examining coursework-based pathways with embedded performance measures as a lower-cost, higher-fidelity alternative for demonstrating subject matter and pedagogical competence. These efforts can be supported with resources to develop and validate alternatives that ensure competence while streamlining pathways to teaching. - Strengthen systems to recruit and prepare aspiring teachers earlier in the educational process, including through community college and high school pathways.

Policies to recruit and begin preparing future teachers earlier in their educational careers can help attract young people into teaching and reduce the overall costs of their preparation. The state could consider investing in “2 + 2” partnerships that allow candidates to begin teacher preparation at a community college, with clear course articulation agreements that enable them to complete teacher preparation and credentialing requirements at a 4-year institution. In addition, expanding high school pathway programs into teaching can also serve as a GYO pipeline for local school districts. Although California has made substantial investments in career technical education (CTE) programs, few of these programs focus on teaching as a career pathway.California Department of Education. (2017). Report to the governor and the Legislature: Evaluation of the Assembly Bill 790, Linked Learning Pilot Program, the Assembly Bill 1330 Local Option Career Technical Education Alternative Graduation Requirement, and the California Career Pathways Trust. Sacramento, CA: Author. (accessed 7/14/2017). - Improve teacher compensation and working conditions to retain strong teachers in the profession.

Given the high cost of living in California overall—and with especially high housing costs in certain regions, such as the Bay Area—efforts to boost compensation may need to be part of state and local strategies to recruit and retain a qualified and diverse teacher workforce. In addition, working conditions influence teachers’ decisions to remain in their school or in the profession altogether.Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. State and local efforts to reduce pupil loads and provide a broader net of wraparound supports for meeting students’ health, mental health, social service, and other needs may reduce teacher burnout and thereby reduce staff turnover rates.Sibley, E., Theodorakakis, M., Walsh, M. E., Foley, C., Petrie, J., & Raczek, A. (2017). The impact of comprehensive student support on teachers: Knowledge of the whole child, classroom practice, and teacher support. Teaching and Teacher Education, 65, 145–156; Daniel, J., Quartz, K. H., & Oakes, J. (2019). Teaching in community schools: Creating conditions for deeper learning. Review of Research in Education, 43(1), 453–480. - Develop strong school leaders who can recruit, develop, support, and retain their staff.

Teachers cite principal support as one of the most important factors in their decisions to stay in a school or in the profession, especially in high-poverty schools.Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Ing, M., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2011). The influence of school administrators on teacher retention decisions. American Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 303–333; Marinell, W. H., & Coca, V. M. (2013). Who stays and who leaves? Findings from a three-part study of teacher turnover in NYC middle schools. New York, NY: Research Alliance for New York Schools; see also: Carver-Thomas, D., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher turnover: Why it matters and what we can do about it. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. California is launching a new effort to provide intensive professional learning opportunities to school leaders through the 21st Century California School Leadership Academy.California Department of Education. (n.d.). 21st Century California School Leadership Academy. (accessed 01/25/20). With a survey of California principals finding that principals receive the least preparation and professional development in how to recruit, develop, support, and retain their staff, these important skills should be a key area of focus going forward.Sutcher, L., Podolsky, A., Kini, T., & Shields, P. M. (2018). Learning to lead: Understanding California’s learning system for school and district leaders. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. - Strengthen state educator workforce data systems to allow the state to examine and manage educator supply and demand more effectively.

California included a $10 million investment in the 2019 budget to develop a statewide cradle-to-career data system. In addition, CTC and CDE have begun efforts to link their data systems. These efforts can allow the state to understand and manage teacher supply and demand more effectively, better guide sound state and local policies, and support continuous improvement at the state and local levels.

Sharpening the Divide: How California’s Teacher Shortages Expand Inequality by Desiree Carver-Thomas, Tara Kini, and Dion Burns is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

This research was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation. Core operating support for LPI is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Cover photo by Allison Shelley for American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action.