Sharpening the Divide: How California’s Teacher Shortages Expand Inequality

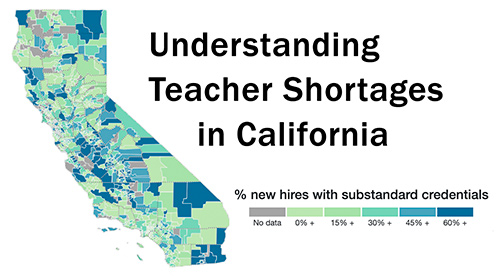

This report was developed as a companion to an online interactive map, Understanding Teacher Shortages in California: A District- and County-Level Analysis of the Factors Influencing Teacher Supply and Demand.

When California students returned to school in fall 2019, hundreds of thousands returned to classrooms staffed by substitutes and teachers who were not fully prepared to teach. In recent years, California has experienced widespread shortages of elementary and secondary teachers as districts and schools seek to restore class sizes and course offerings cut during the Great Recession. Schools experiencing shortages of fully certified teachers often respond by cutting courses, increasing class sizes, and hiring substitutes and teachers on substandard credentials. Although statewide data reveal a deepening shortage across the state, teacher supply and demand factors vary across districts, and as a result, there can be stark disparities in shortages both among and within districts.

This report examines the most recent publicly available data from the California Commission on Teacher Credentialing (CTC) and public- and restricted-use student and staffing data from the California Department of Education (CDE) to highlight the status of teacher supply, demand, and shortages, as well as teacher diversity, in California. The report details the significance of these supply and demand factors and demonstrates how these conditions vary throughout the state. In addition, the report summarizes recent state investments in addressing teacher shortages and examines potential policy solutions to mitigate ongoing shortages. While this report is based largely on data that predates the COVID-19 pandemic, it discusses the key factors now emerging as the pandemic affects California’s teacher workforce.

Is There Still a Teacher Shortage in California?

One of the best indicators of teacher shortages is the prevalence of substandard credentials or permits, which by law should be issued only when fully credentialed teachers are not available. In 2017–18, California issued more than 13,000 intern credentials, permits, and waivers, nearly triple the number issued in 2012–13. The growing number of substandard credentials issued by the state is an indicator that teacher supply continues to be insufficient to meet the demand for those positions.

Teachers on substandard credentials and permits are not equally distributed across the state. Statewide, about one in three teachers who were new to their districts in 2017–18 were teachers on substandard credentials. However, at one end of the spectrum, roughly 15% of California districts did not hire any teachers on substandard credentials in 2017–18. In a roughly equal number of districts, representing many more students from low-income families (72% vs. 52%), more than half of new hires had substandard credentials.

Analysis of statewide teacher supply and demand factors indicates that there are three main factors driving shortages in California: the decline in teacher preparation enrollments, increased demand for teachers, and teacher attrition and turnover. However, the relative weight of supply and demand factors can vary from district to district.

Teacher Supply and Demand Factors

Teacher supply is composed of the total teacher workforce, including new entrants to teaching and re-entrants, or those who have left teaching but choose to return. New entrants include those who are fully prepared and those who have substandard credentials and permits. Also important are the characteristics of teachers entering and staying in the profession, including teacher diversity.

- Although new hires and beginning teachers can be assets to a growing district—and an expected component of any district’s teacher supply—research shows that students benefit from a stable and substantially experienced teacher workforce. In 2017–18, new hires (beginning and veteran teachers who are in their first year of service to their district) made up 10% of California’s teacher workforce. About 5% of districts, though, had no new hires in 2017–18, while, in contrast, roughly the same number of districts had 40% or more new hires. These districts with the highest proportions of new hires typically have turnover rates twice as high as districts with average or below-average proportions of new hires.

- Beginning teachers—those in their first or second year of teaching—comprise 12% of California’s teacher workforce overall. Roughly 10% of districts employ fewer than 3% beginning teachers, and the majority of those districts had no beginning teachers in 2017–18. Meanwhile, about one in four districts employs 20% or more of these teachers, who are typically less effective than experienced teachers. When schools have large numbers of novices, they often lack a sufficient number of expert veterans to support these new teachers.

- Re-entrants, or California teachers who return to teaching after having left for a period of time, are an important component of teacher supply, making up about a quarter of new hires in recent years. Nearly 20% of teachers who left after 2015–16 returned to teaching in the state in 2017–18, with about 12% of leavers returning to the same district that they left within a year.

- A growing body of research shows that being taught by teachers of color is associated with benefits to all students, with students of color, especially Black students, experiencing boosts in academic achievement, graduation rates, and aspirations to attend college, among other benefits. With 34% teachers of color statewide, the proportion of teachers of color in California exceeds the national average of 20%. Nonetheless, 9% of California districts had no teachers identifying as people of color in 2017–18, and 58% had fewer than 20%.

Demand factors indicate the need districts and counties have to hire additional teachers. These factors include teacher attrition and turnover, student–teacher ratios, recent and projected changes in student enrollment, and the percentage of teachers who are age 50 and older or 60 and older, which can signal the extent to which imminent retirements might create demand for new teacher hires.

- Teacher attrition (measuring teachers who leave teaching) and turnover (measuring teachers who leave teaching or move between districts) are primary drivers of statewide shortages. Between 2016–17 and 2017–18, 12% of California teachers either left public school teaching in the state (9%) or moved to another California district (3%). On one end of the spectrum, nearly 1 in 10 districts have turnover rates under 5%. At the other end of the spectrum, roughly 1 in 10 districts have turnover rates of 25% or more. Districts with higher turnover rates also have greater proportions of students from low-income families compared to those with the lowest turnover rates.

- Each year districts estimate the number of teachers they will need to hire to replace teachers who have left or to fill new positions. Between 2013–14 and 2017–18, the number of teachers districts estimated needing to hire each year increased by 43%. Increases in teacher demand were due, in part, to districts hiring new teachers to reduce student–teacher ratios, which increased after the Great Recession to the highest level in the United States (24:1, as compared to the national average of 15:1). Although California is gradually nearing its pre-recession student–teacher ratio of 21:1, the state would need more than 4,100 additional teachers per year in order to reach that benchmark. In 2017–18, roughly 60% of districts still had student–teacher ratios that were larger than their pre-recession levels.

- Although statewide student enrollment is projected to decline by about 4% between 2017–18 and 2027–28, trends differ across the state. Total student enrollment in the state was essentially unchanged between 2016–17 and 2017–18, but nearly a quarter of districts experienced enrollment increases or decreases of 5% or more.

- In part because of teacher layoffs during the Great Recession, California’s teacher age distribution has shifted to include more mid- and late-career teachers and fewer early-career teachers. About 40% of the teacher workforce is age 50 or older, and the 14% of California teachers age 60 and older are likely to retire within the next 5 to 10 years.

The Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The COVID-19 crisis is likely to impact teacher demand and supply in complex ways: The pandemic could increase demand as additional staff are needed to ensure schools can safely reopen with appropriate physical distancing in place; it could also trigger shortages by exacerbating turnover, as many teachers have indicated they may not return to school under current circumstances. At the same time, teacher layoffs could occur if revenues drop as the state and districts grapple with the economic effects of the crisis. In any of these scenarios, long-standing shortages in high-need fields and schools are likely to continue.

Addressing California’s Teacher Shortage

In recent years, California has begun to take a proactive approach to addressing teacher shortages. Over the past 4 years, the state Legislature has enacted several initiatives and invested nearly $300 million to build the teacher pipeline and recruit and retain well-prepared teachers. While the largest investments are for programs that have not yet been fully launched, and many of the other investments are for programs that will take a number of years to produce graduates, efforts to rebuild the teaching force are beginning to yield modest results. However, nearly all of these initiatives were funded only on a one-time basis in the state budget. Given the severity of ongoing shortages and the disproportionate impact of shortages on particular districts, subject areas, and student populations, California may need to consider further action to address chronic shortages. Based on research on attracting and retaining teachers, we have identified eight strategies that state and local agencies in California can implement in order to address ongoing teacher shortages, particularly in high-need fields and schools. These include:

- Maintaining and expanding high-retention pathways into teaching, such as teacher residencies and Grow-Your-Own pathways.

- Providing service scholarships to all teacher candidates who complete preparation and commit to teach in high-need fields and locations.

- Ensuring equitable access to mentoring and induction programs for novice teachers.

- Streamlining requirements for entry into the profession by considering multiple pathways for demonstrating competence for both in-state and out-of-state entrants to the profession.

- Strengthening systems to recruit and prepare aspiring teachers earlier in the educational process, including through community college and high school pathways.

- Improving teacher compensation and working conditions to retain strong teachers in the profession.

- Developing strong school leaders who can recruit, develop, support, and retain their staff.

- Strengthening state educator workforce data systems to allow the state to examine and manage educator supply and demand more effectively.

Sharpening the Divide: How California’s Teacher Shortages Expand Inequality by Desiree Carver-Thomas, Tara Kini, and Dion Burns is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

This research was supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the S.D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation. Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Heising-Simons Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, and William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. We are grateful to them for their generous support. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.

Cover photo by Allison Shelley for American Education: Images of Teachers and Students in Action.