Summary

The Texas Education Agency launched the High-Quality, Sustainable Residencies Program—a grant-funded effort to establish and sustain teacher residencies—in 2021. Part of the Texas COVID Learning Acceleration Supports (TCLAS) initiative, this grant supported residency programs across the state, implemented through partnerships between school districts and educator preparation programs (EPPs), with paid placements for more than 2,000 residents. The grant also provided technical assistance for these districts to adopt “strategic staffing” models to sustain paid residencies after the end of grant funding. This brief highlights crucial features and requirements of the TCLAS residency grant program that have continued to shape residency-focused implementation and enable sustainability efforts at both the state and local levels. These features include required residency model and district–EPP partnership elements, shared residency program governance between partners, and technical assistance aimed at building local and regional capacity to embed strategic staffing structures for sustainable funding.

This brief is based on the report Teacher Residencies in Texas: Supporting Successful Implementation.

Introduction

In 2021, the Texas Education Agency (TEA) undertook a program to establish and sustain teacher residencies across the state. The High-Quality, Sustainable Residencies Program, underwritten by federal COVID-19 relief funds, was one of 10 grant programs in the $1.4 billion Texas COVID Learning Acceleration Supports (TCLAS) initiative. Allotted just over $90 million, this TCLAS residency grant supported K–12 school districts that offered residency programs in partnership with state-designated educator preparation programs (EPPs).McLoughlin, J., & Yoder, M. (2022, January 13). Sustainable teacher residencies in Texas [Presentation slides]. Texas Education Agency. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NwfxHLxIA4bm4R4vz7zNrTG8LXCr_RFY/view; Texas Education Agency. (2021). The Texas COVID Learning Acceleration Supports (TCLAS) Program. https://tea.texas.gov/texas-schools/health-safety-discipline/covid/tclas-guidance-document.pdf From 2021 through 2024, TCLAS provided funding and technical assistance to 85 district–EPP partnerships and paid placements for more than 2,000 residents.Bland, J. A., Wojcikiewicz, S. K., Darling-Hammond, L., & Wei, W. (2023). Strengthening pathways into the teaching profession in Texas: Challenges and opportunities. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/957.902; McLoughlin, J., & Yoder, M. (2021, July 13). TCLAS deep dive webinar: Decision 5: Residency program support [Presentation slides]. Texas Education Agency. https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/covid/tclas-decision-point5-presentation-21.pdf The grant also provided technical assistance for these districts to adopt “strategic staffing” models so they could reconfigure educator positions to reallocate resources toward sustaining paid residencies after the end of grant funding.Texas Education Agency. (2021). The Texas COVID Learning Acceleration Supports (TCLAS) Program. https://tea.texas.gov/texas-schools/health-safety-discipline/covid/tclas-guidance-document.pdf

This work continues as districts seek to make residencies sustainable, applying savings achieved through strategic staffing along with additional investments justified by the quality of residency graduates’ preparation. A new residency credential was also created in April 2024 by the Texas State Board for Educator Certification (SBEC) and adopted by the Texas State Board of Education in September of that year. These changes codified many of the residency features required for TCLAS EPPs and resulted in the creation of a formally recognized teacher residency preparation pathway leading to a new state teaching certificate, the Enhanced Standard Certificate. The SBEC issued the first 15 program approvals in the Texas Teacher Residency Preparation Route in December 2024, and graduates of these programs will receive the new Enhanced Standard Certificate, which can support district efforts to hire residency completers while enabling employment incentives such as higher salaries.Texas Education Agency. (2024, December 11). Educator preparation program support. Texas Educator Preparation Programs Newsletter. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/TXTEA/bulletins/3c65b7e

High-Quality Residencies

The TCLAS residency grant program was based on collaboration between EPPs and districts. In the words of the TEA, “In high-quality teacher residency models, the EPP and [district] have shared ownership over the preparation, support, and success of the teacher resident.”McLoughlin, J., & Yoder, M. (2021, July 13). TCLAS deep dive webinar: Decision 5: Residency program support [Presentation slides]. Texas Education Agency. https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/covid/tclas-decision-point5-presentation-21.pdf To this end, TCLAS requirements called upon EPPs and districts, working in partnership, to play specified roles in implementing TCLAS residencies.

District Requirements

To qualify for TCLAS funding, districts had to meet state-defined requirements communicated through the terms of the grant program. The TCLAS application required districts to assent to a list of “assurances” laying out essential partnership features and committing districts to actions that included the following:

-

engage in shared program governance through required district–EPP meetings focused on data analysis and residency program improvement;

-

work with partner EPPs to develop shared profiles of teacher residents and of mentor teachers, along with recruiting plans for the former and training plans for the latter;

-

establish yearlong clinical placements of at least 3 days per week for residents;

-

adopt one of several “innovative staffing” models to free up sustainable residency funding;

-

facilitate active participation by leaders from districts, schools, and the EPP in technical assistance activities focused on innovative staffing; and

-

provide $20,000 stipends to up to 20 residents per school year for 3 years.Texas Education Agency. (2021). The Texas COVID Learning Acceleration Supports (TCLAS) Program. https://tea.texas.gov/texas-schools/health-safety-discipline/covid/tclas-guidance-document.pdf

Districts were also required to produce a memorandum of understanding for each residency partnership to demonstrate that they had an existing arrangement with a state-vetted EPP.

TEA structured the TCLAS district application process to be more accessible, less complex, and less time-consuming than a typical grant application.McLoughlin, J., & Yoder, M. (2021, July 13). TCLAS deep dive webinar: Decision 5: Residency program support [Presentation slides]. Texas Education Agency. https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/covid/tclas-decision-point5-presentation-21.pdf The grant was also noncompetitive; any district that met all of the state requirements would receive an award. These features enabled the launch of residencies within the window available: The district application opened in mid-July 2021, submissions were due a month later, and preliminary award notifications were sent by September 10, 2021. Districts completed a second, more detailed stage of the application, concurrent with the launch of the first year of their residency partnerships, in fall 2021. Final awards were disbursed starting in December 2021. This two-stage timeline allowed residency partnerships to support their 2021–22 cohort with paid stipends even as the full application process continued.

Despite the straightforward design of the application process, TEA staff estimated that around one third of districts that applied for TCLAS residency grant funding did not receive it. The main barrier for these districts, according to TEA staff, was that they did not meet the requirement to have an established partnership with a Vetted Teacher Residency Program provider. In multiple cases, districts listed partnerships on their applications that had not yet been set up.

Like the application process, TCLAS reporting and accountability requirements were designed to be straightforward. For each year of TCLAS implementation, districts were required to report the number of resident slots filled, resident demographics, number and type of certifications earned by residency completers, and number of residency completers hired as full-time teachers in the district. Accountability provisions consisted of a boilerplate TEA oversight clause, included in all TEA grants, requiring the return of grant monies if grantees were found to be out of compliance with grant assurances.Texas Education Agency. (n.d.). 2023–2025 Grow Your Own Grant Program, Cycle 6. https://tea.texas.gov/finance-and-grants/grants/grants-administration/grants-awarded/competitive-grant-application/2023-2025-grow-your-own-grant-program-cycle-6 (accessed 09/21/24). This level of oversight required less specific reporting and less district staff time compared with other TEA grants. TEA staff characterized their approach to accountability as collaborative and focused on correcting rather than ensuring compliance. This collaborative approach was adopted in alignment with the overall TCLAS goal of establishing and sustaining as many residency programs as possible.

Educator Preparation Program Requirements

To be eligible for participation in TCLAS residency partnerships, EPPs first had to meet the state definition of “a high-quality teacher residency program,” in which:

The teacher candidate is paired with an experienced, highly effective mentor teacher for a full year of clinical training/co-teaching in a K–12 classroom (minimum of 21 hours per week for a full year). Residencies take place at the undergraduate and postbaccalaureate levels. In some cases, residents receive a stipend during the yearlong residency.Texas Education Agency. (n.d.). Vetted Teacher Residency Program list: 2023–24. https://tea.texas.gov/texas-educators/preparation-and-continuing-education/program-provider-resources/vtrp-list-23-24.pdf

Each EPP that met this threshold could be designated as a Vetted Teacher Residency (VTR) eligible for participation in TCLAS. The designation process began in May 2021, 2 months before the opening of the district TCLAS application, when EPPs were notified of the opportunity to apply for VTR status. EPPs were required to submit evidence of required program features, including data-driven collaboration with a local school district, use of co-teaching models in a yearlong clinical experience, facilitation of resident placements by EPP clinical faculty, and engagement in strategic staffing efforts to support paid teacher residencies. The application was meant to require between 1 and 2 hours to complete, a relatively short span of time for a TEA grant, reflecting the approach of the district TCLAS applications.Texas Education Agency. (2021, May 18). Educator preparation program support. Texas Educator Preparation Programs Newsletter. https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/TXTEA/bulletins/2d9856e?reqfrom=share

EPP applications were scored by a third-party vendor hired by the TEA. By the opening of district TCLAS applications in July 2021, 15 EPPs had received the VTR designation. This total rose to 27 EPPs before the start of the 2022–23 school year and then to 37 before the 2023–24 school year.The number of VTRs is out of 120 approved EPPs total in Texas (2023–24) and 74 traditional institutions of higher education. Texas Education Agency. (2024). Educator preparation programs in Texas [Interactive map]. https://tea-texas.maps.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/8fdeed6e29b741ba8bac151ac023186d (accessed 09/21/24). Of these 37 EPPs, most were 4-year colleges and universities. There were also two community colleges, four regional education service centers, one alternative graduate school of education, and one nonprofit provider.Texas Education Agency. (n.d.). Vetted Teacher Residency Program list: 2023–24. https://tea.texas.gov/texas-educators/preparation-and-continuing-education/program-provider-resources/vtrp-list-23-24.pdf

All of the 15 original EPPs that received VTR status had residency programs running before the launch of the vetting process. They had already built internal systems, funded and hired new positions to support teacher residents (e.g., site coordinators, clinical faculty who observe residents and support their progress), and engaged in shared residency planning and governance with local school districts. The prior experience that vetted EPPs brought to TCLAS illustrates a vital feature of the residency grant program at its launch: District–EPP partnerships were built on the experience of EPPs already implementing state-vetted teacher residencies. As articulated in a TEA presentation, the design of the TCLAS grant was “grounded in work already underway in the state.”McLoughlin, J., & Yoder, M. (2022, January 13). Sustainable teacher residencies in Texas [Presentation slides]. Texas Education Agency. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NwfxHLxIA4bm4R4vz7zNrTG8LXCr_RFY/view

Sustainable Residencies

Among the design features of the TCLAS grant was its focus on the “sustainability of postgrant funding based on lessons learned in similar grants.”McLoughlin, J., & Yoder, M. (2022, January 13). Sustainable teacher residencies in Texas [Presentation slides]. Texas Education Agency. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NwfxHLxIA4bm4R4vz7zNrTG8LXCr_RFY/view Sustainability of paid residencies was addressed by the multiyear technical assistance (TA) provision of TCLAS. Specifically, TCLAS TA was intended to “support the district to continue to pay resident and mentor wages beyond grant funding.”Texas Education Agency. (2021, December 28). Educator residencies and innovative staffing models [Presentation slides]. https://www.sfasu.edu/docs/college-education/meetings/TEA-educator-residencies-and-staffing-models.pdf This focus illustrates the central role that districts played in TCLAS residencies beyond applying for and receiving TCLAS funding. Having launched paid residencies, districts were tasked with using local funding to sustain them after the grant ended. Partner EPPs participated in TCLAS TA, but the financial responsibility rested with the districts.

Sustainability and Strategic Staffing

Sustainability was a primary TCLAS goal, and committing to maintain paid residencies at the $20,000 level beyond TCLAS funding was an essential requirement for applicant districts. The route to local stipend funding was through strategic staffing. As stated in the grant assurances:

The applicant must assure that they will design and implement an innovative staffing model plan that will ensure that the teacher residency model will be sustainable, fully funded by district dollars, by [school year] 2024–25. The plan must include sustainable funding for teacher resident stipends/salaries.Texas Education Agency. (2021). The Texas COVID Learning Acceleration Supports (TCLAS) Program. https://tea.texas.gov/texas-schools/health-safety-discipline/covid/tclas-guidance-document.pdf

As the TEA defined it, strategic staffing design meant districts would be “making decisions driven by instructional needs in the district to reallocate underutilized, existing local dollars to fund paid teacher residencies for teacher candidates.”Texas Education Agency. (2021, December 28). Educator residencies and innovative staffing models [Presentation slides]. https://www.sfasu.edu/docs/college-education/meetings/TEA-educator-residencies-and-staffing-models.pdf Within this broad definition, the TEA highlighted three specific functions of strategic staffing models: (1) freeing up funding to pay resident stipends; (2) establishing sustainable residency programs; and (3) forming “the foundation of meaningful educator pipelines” for districts through which residents train on “district-specific competencies and practices.”Texas Education Agency. (2021, December 28). Educator residencies and innovative staffing models [Presentation slides]. https://www.sfasu.edu/docs/college-education/meetings/TEA-educator-residencies-and-staffing-models.pdf

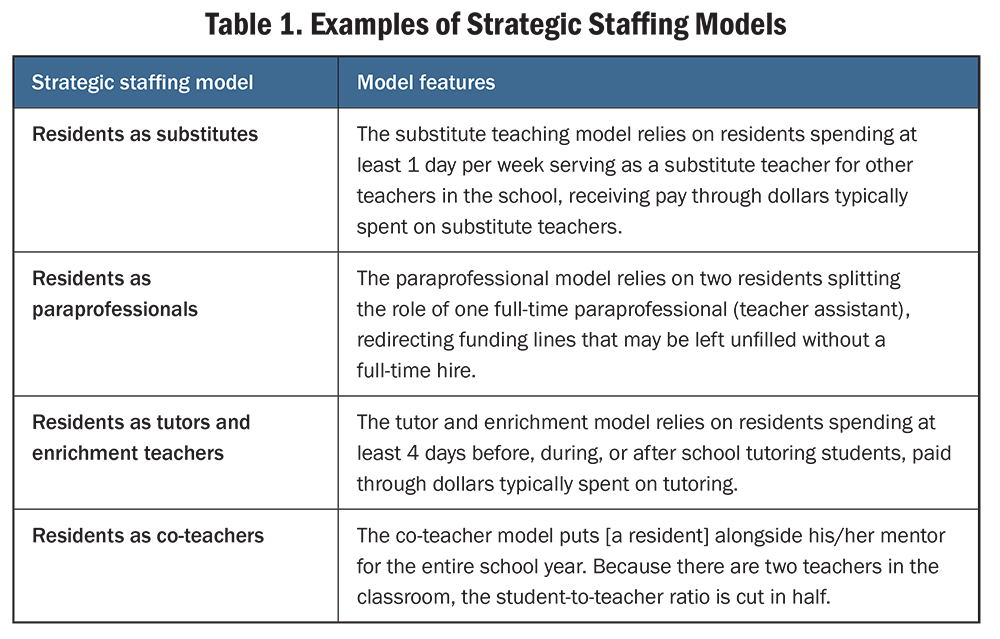

TCLAS strategic staffing models could take a variety of forms, and districts had choices in how to implement them. The TEA highlighted four potential staffing models in presentations to EPP and district educators in 2021, exemplifying this variation (see Table 1).

It is important to note that strategic staffing arrangements were intended to enhance, not detract from, residents’ clinical preparation. When residents fill educator roles, these roles have the potential to eclipse resident training. The TEA stressed that while residents may “fill instructional needs” in strategic staffing models, doing so “should also be a benefit to their own preparation.”Texas Education Agency. (2021, December 28). Educator residencies and innovative staffing models [Presentation slides]. https://www.sfasu.edu/docs/college-education/meetings/TEA-educator-residencies-and-staffing-models.pdf For districts to maintain residents’ focus on their preparation, the TEA emphasized the need for “intentional planning and support” from both districts and EPPs.Texas Education Agency. (2021, December 28). Educator residencies and innovative staffing models [Presentation slides]. https://www.sfasu.edu/docs/college-education/meetings/TEA-educator-residencies-and-staffing-models.pdf

Technical Assistance and Sustainability

TA providers worked directly with districts and their EPP partners as they implemented strategic staffing to sustain paid residencies.McLoughlin, J., & Yoder, M. (2022, January 13). Sustainable teacher residencies in Texas [Presentation slides]. Texas Education Agency. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NwfxHLxIA4bm4R4vz7zNrTG8LXCr_RFY/view Among the TCLAS grant assurances were requirements that each district would engage with a TA provider. Specifically, the assurances stated:

A designated team of district, campus, and partner EPP-level leaders will actively participate in innovative staffing model training and technical assistance support activities beginning in [school year] 2022–23. The designated team must include at least one district and EPP-level leader and a selected set of leaders from each campus on which teacher residents are placed.Texas Education Agency. (2021). The Texas COVID Learning Acceleration Supports (TCLAS) Program. https://tea.texas.gov/texas-schools/health-safety-discipline/covid/tclas-guidance-document.pdf

TA for implementing strategic staffing was the one dedicated mechanism for sustaining paid residencies after TCLAS funding ended. Technical assistance focused on the district level, though strategic staffing models were intended to be developed collaboratively as the “product of districts and their EPP partners working alongside a strategic staffing technical assistance provider,” as the TEA put it.Texas Education Agency. (2021, December 28). Educator residencies and innovative staffing models [Presentation slides]. https://www.sfasu.edu/docs/college-education/meetings/TEA-educator-residencies-and-staffing-models.pdf Leaders and staff from both EPPs and districts were required to participate in TA activities, including quarterly webinars during the first grant year and ongoing trainings and meetings.

Two entities were originally approved as TCLAS TA providers: Public Impact and US PREP.Texas Education Agency. (2021). The Texas COVID Learning Acceleration Supports (TCLAS) Program. https://tea.texas.gov/texas-schools/health-safety-discipline/covid/tclas-guidance-document.pdf These providers were chosen by the TEA for their experience in supporting EPP transformations to teacher residencies and district implementation of strategic staffing models. As the grant proceeded, US PREP became the primary TA provider across the state, while Public Impact continued to support the subset of districts with which it had partnered pre-TCLAS. In another evolving role, in addition to providing TA to districts, US PREP took on the training of Education Service Centers (i.e., regional support centers) staff to provide TA.McLoughlin, J., & Yoder, M. (2021, July 13). TCLAS deep dive webinar: Decision 5: Residency program support [Presentation slides]. Texas Education Agency. https://tea.texas.gov/sites/default/files/covid/tclas-decision-point5-presentation-21.pdf

US PREP: University–School Partnerships for the Renewal of Educator Preparation

The University–School Partnerships for the Renewal of Educator Preparation (US PREP) National Center, housed at Texas Tech University, was founded in 2015 to support university-based residency programs. By 2024, the US PREP network had grown to include 30 universities in six cohorts. Network members make a 4-year commitment to pilot and scale teacher residencies, aiming “to ensure teachers are prepared to work in the classroom on Day 1 after graduation,” a goal also articulated as having teachers who are “Day 1 ready.”

Among residency elements that US PREP deems essential are yearlong clinical teaching experiences under the guidance of trained mentor teachers, with strong supervision and coaching through the use of co-teaching models; district partnerships featuring shared planning, decision-making, and governance informed by data sharing; clinical educator preparation program (EPP) faculty (i.e., site coordinators) who supervise residents and bridge district–EPP partnerships through communication and shared meeting facilitation; and practice-based coursework aligned to clinical placements and keyed to regular teacher candidate evaluation instruments that are central sources of data for continuous improvement.

Sources: Mellon, E. (2017, June 20). UH makes strides to ensure teachers are ready on day one. UH College of Education; US PREP National Center. (n.d.). Our model: Transforming teacher preparation; US PREP National Center. (2023). Why teacher residencies need to be the standard.

Technical Assistance and Regional Education Service Centers

TCLAS technical assistance was intended to operate on multiple levels with interconnected goals: establishing sustainable residencies in local contexts, building capacity for regional Education Service Centers (ESCs) to provide this technical assistance, and improving teacher pipelines on a statewide scale. This multilevel capacity building was essential in enabling the state to support improvement across the teacher pipeline at the local, regional, and state levels.

The provision of targeted local support across a large state was possible, in part, because of the position of regional ESCs in Texas. Embedded between the state agency level and the local district–EPP level, ESCs are authorized service organizations and are paid by districts for services, including technical assistance. As service organizations, ESCs do not exercise regulatory power, and “participation … in services of the centers is voluntary” for schools.Texas Education Agency. Education Service Centers. https://tea.texas.gov/about-tea/other-services/education-service-centers (accessed 07/03/2025). Enabling ESCs to add strategic staffing TA to their menu of services was a step toward long-term, statewide residency sustainability since this new capacity would be available both to TCLAS districts and other districts launching residencies post-TCLAS.

The mechanism for developing ESCs’ capacity through TCLAS was the establishment of an ESC Fellowship Program. ESC fellowships provided training for center staff, known as ESC fellows, tasked with providing strategic staffing TA to TCLAS districts. Training for ESC fellows was conducted by US PREP and carried out while the ESC fellows provided TCLAS technical assistance.McLoughlin, J., & Yoder, M. (2022, January 13). Sustainable teacher residencies in Texas [Presentation slides]. Texas Education Agency. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NwfxHLxIA4bm4R4vz7zNrTG8LXCr_RFY/view During the 2022–23 school year, 11 ESCs worked with US PREP to become strategic staffing TA providers. When TCLAS funding ended in 2024, all 20 ESCs had trained fellows on staff.

To ensure alignment between the TA providers and district-level implementation statewide, TEA staff provided oversight by attending biweekly meetings with US PREP trainers. In these meetings, agency staff provided input on the structure of support for ESCs and districts, determined focus areas to address moving forward, and answered questions. Additionally, designated TEA staff for each region attended in-person TA provider trainings, monthly coaching meetings, and field observations. These arrangements allowed for the coordination of different streams of TCLAS work over the course of implementation.

Priorities of Strategic Staffing Technical Assistance

As previously described, strategic staffing, also called innovative staffing, refers to district-level efforts to reconfigure how educator positions (e.g., substitute teachers, tutors, instructional aides) are funded and filled. Districts implementing strategic staffing strategies assigned residents to take on instructional support positions for time-limited periods, frequently 1 day per week. The money allocated for these positions could then be redirected toward supporting resident stipends.

Illustrating the strategic staffing concept, a TCLAS TA provider shared an example of how districts engaged with the strategic staffing process:

You can think differently about how to leverage residents. … Districts don’t have extra money, so how are you using the money you already have? Well, [if I were] a building principal, I would much rather say I’m going to have these residents be my primary substitute teachers, and we’re going to do it in a strategic way so it’s not taking away from their teacher preparation. … [Or] I can use these strategic staffing models to think differently about who I go to first for before- and after-school tutoring or even before- and after-school care.

The reconfiguration of educator roles was a novel response to the problem of residency sustainability, and it brought with it some novel challenges. One such challenge, which was anticipated by TA providers, was that strategic staffing roles might end up demanding too much time and effort from residents, detracting from their learning in their co-teaching placements. As one TA provider staff member noted:

If we’re not careful, I would say that the [strategic staffing] designing that’s happening with the districts could turn a resident into a kind of intern, where they’re being left alone to teach too much, or they’re being asked to sub too often, or they’re not getting the full benefits of the residency.

US PREP, as both a direct TA provider and an ESC staff trainer, aimed to keep preparation front and center. The training US PREP staff provided to ESC fellows went far beyond the details of strategic staffing, digging into the fundamental elements of high-quality residencies and their purposes in the teacher pipeline. As one US PREP trainer of trainers explained:

In my opinion, at their best, [the ESC TA providers] will have a strong understanding of the importance of the elements of a residency, [not just] the elements of a paid residency. … The whole point of this is that at the end, we [produce] highly trained and prepared teachers. If that’s your foundation, everything else that happens builds off of that.

Communication, Innovation, and Technical Assistance

School and district administrators and EPP staff were consistent in their positive opinions of the TCLAS strategic staffing TA they received. They noted that the TA gathered the right personnel to make decisions about strategic staffing. They also expressed appreciation for the essential role that TA providers played in convening and conducting these meetings.

EPP and district staff also appreciated that TA providers, working with multiple districts, could draw upon insights from across these contexts to contribute to local problem-solving. This occurred as ESC fellows met regularly with their US PREP trainers and with fellows from other regions. As one fellow described: “We meet as a team … to share those lessons learned, to talk about ideas. … This is how we build capacity.” From the EPP perspective, an administrator described the process by which insights gained in the course of TA to one district were shared with other districts:

I don’t think we could have thought through all the intricacies of it without someone guiding us. … Every time you come up against a brick wall, we could ask, “So who else is coming up against this? How did they solve it?” And she [the TA provider] would go out and say, “OK, I’ve talked to x, y, and z … and this is how they did it, and someone else did it like this, and another [district], they haven’t figured it out yet, either.” We could always draw from a network.

Communication and feedback were further enhanced by the dual role of US PREP, which acted as both a direct TA provider and an ESC training provider. Training sessions included materials derived from previous TA experience and improved through cycles of feedback. As part of the training for ESC fellows, US PREP trainers also simulated TA meetings and shared insights from their own experiences providing TA to districts. These sessions also allowed ESC fellows to gain experience in low-stakes environments as they practiced listening for common issues, answering questions, and addressing obstacles to strategic staffing implementation.

One additional insight about TA provided by US PREP staff and ESC fellows was their realization, over the course of TCLAS implementation, that capacity building at the ESC level was analogous to capacity building at the EPP or district level, and both were analogous to classroom teaching. One US PREP staff member described these parallels:

Just like teaching, you know all the mistakes people—the kids—are going to make. You know the common errors, and you can plan for them. I think as somebody who has done the TA and then also coaches and trains people on the TA, it’s really hard your first year. … It’s like your first year of teaching. You don’t know what’s coming, and then you make mistakes, and they have ripple effects down the road. So as coaches we say, “This parameter, guys, has some holes in it. You need to go back and fix those.” But often, in training the TA provider, they don’t realize their own errors until they’ve made them.

That US PREP was able to quickly utilize insights like these, iterating on and improving on TA training in real time, had one additional, related benefit: US PREP trainers had the opportunity to model the very approach to data-driven continuous improvement that would be implemented, in part under the guidance of ESC fellows, in TCLAS district–EPP partnership and strategic staffing work.

Conclusion

The High-Quality, Sustainable Residencies Program provides an example of how states can incentivize and enable districts and EPPs to build and scale sustainable teacher residency programs. By requiring that grantees include key features for success in their residency programs, enabling close partnerships and offering TA to adopt strategic staffing models, Texas has taken steps toward establishing a pipeline to provide a high-quality workforce.

Developing Sustainable Teacher Residencies in Texas (brief) by Steven K. Wojcikiewicz is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the author and not those of our funders.