Investing in Teacher Residencies: Sustaining Texas’s Momentum to Prepare High-Quality Teachers

Summary

Texas has made a substantial investment in teacher residencies—a research-based approach to high-quality, practice-based teacher preparation. At the direction of the legislature, the Texas Education Agency (TEA) launched this large-scale expansion of residencies to improve access to high-quality preparation and thereby help mitigate ongoing teacher workforce challenges. The research summarized in this brief demonstrates how Texas’s investment has supported improvements in candidate competence, instructional preparedness, teacher preparation programming, and district hiring practices. The TEA made important design decisions in expanding residencies that helped spur these successes. The brief recommends strategic approaches to funding mentor and resident stipends and technical assistance for program design that can maintain progress in expanding this successful teacher workforce initiative.

This brief is based on two LPI reports, Investing in a High-Quality Teacher Workforce: Lessons From Texas Teacher Preparation Programs and Teacher Residencies in Texas: Supporting Successful Implementation.

Introduction

Texas has experienced severe teacher shortages for more than a decade, largely driven by early-career teachers leaving the classroom,Templeton, T., Horn, C., Sands, S., Mairaj, F., Burnett, C., & Lowery, S. (2022). 2022 Texas teacher workforce report. University of Houston College of Education. https://charlesbuttfdn.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Texas-Teacher-Workforce-Report-2022.pdf and the Texas teacher attrition rateLanda, J. (2024). Employed teacher attrition and new hires 2014–15 through 2023–24. Texas Education Agency.

https://tea.texas.gov/reports-and-data/educator-data/employed-teacher-attrition-and-new-hires-2023-2024.pdf exceeds the national averageTaie, S., & Lewis, L. (2023). Teacher attrition and mobility: Results from the 2021–22 Teacher Follow-Up Survey to the National Teacher and Principal Survey [NCES 2024-039]. National Center for Education Statistics.

https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2024039 by more than 50%. To address vacancies, many Texas districts rely on short-term approaches that can ultimately undermine student learning, including hiring underqualified and underprepared teachers.Texas Education Agency. (2024, March). Teacher employment, attrition, and hiring [Presentation slides].

https://tea.texas.gov/texas-educators/superintendents/teacher-employment-attrition-and-hiring-march-2024.pdf More than two thirds of first-year teachers in Texas now either enter the profession via alternative routesBland, J. A., Wojcikiewicz, S. K., Darling-Hammond, L., & Wei, W. (2023). Strengthening pathways into the teaching profession in Texas: Challenges and opportunities. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/957.902 that abbreviate coursework and allow candidates to become teachers of record while still training, or they hold no certification at allLPI analysis of Landa, J. (2024, March). The pathway of an employed new hire, 2014–15 through 2023–24. Texas Education Agency. https://tea.texas.gov/reports-and-data/educator-data/employed-teacher-attrition-and-new-hires-2023-2024.pdf. Note that in order to reflect new-to-profession teachers only, teachers returning to the workforce after being licensed in previous years are excluded from the data set in this analysis. based on a waiver that “districts of innovation” can receive. These accelerated pathways enable districts to fill classroom vacancies more quickly, but they are not long-term solutions to the teacher shortage. Research shows that candidates coming through these pathways leave the profession at much higher rates than candidates prepared with a full complement of coursework and clinical experience,Kirksey, J. J., & Gottlieb, J. J. (2024). Teacher preparation in the wild west: The impact of fully online teacher preparation and uncertified teachers in Texas [White paper]. Texas Tech University Center for Innovative Research in Change, Leadership, and Education. https://hdl.handle.net/2346/97797; University of Texas at Austin College of Education & Educate Texas. (2022). Texas educator preparation pathways study: Developing and sustaining the Texas educator workforce. https://issuu.com/texaseducation/docs/texas_educator_prep_pathways_study_issuu and students taught by alternatively prepared teachers and uncertified teachers in the state achieve at much lower levels than students taught by traditionally prepared teachers.Marder, M., David, B., & Hamrock, C. (2020). Math and science outcomes for students of teachers from standard and alternative pathways in Texas. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 28, 27. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.28.4863; Kirksey, J. J. (2024, July). Amid rising number of uncertified teachers, previous classroom experience proves vital in Texas [White paper]. Texas Tech University Center for Innovative Research in Change, Leadership, and Education. https://hdl.handle.net/2346/98166

Texas has adopted paid teacher residencies as one high-leverage strategy for sustainably addressing the teacher shortage and reducing long-term costs.Dennis, H., & DeMoss, K. (2021, April 16). The residency revolution: Funding high-quality teacher preparation. Prepared To Teach. https://educate.bankstreet.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1012&context=pt This research-validated, gradual-release approach, modeled after the medical residency system, pairs each teacher candidate with an experienced, highly effective mentor teacher for a full year of clinical training and co-teaching in a K–12 classroom for a minimum of 21 hours per week. This clinical training is highly aligned with the practice-based university coursework that teacher residents complete.

This brief describes key outcomes of Texas’s investment in teacher residencies based on interviews with teacher residents, residency completers, and educator preparation program and school district administrators, faculty, and staff. It then provides policy recommendations to maintain Texas’s meaningful progress in building out teacher residencies.

Texas’s Investment in Teacher Residencies

Residency pathways in Texas have been growing at state educator preparation programs (EPPs) over the past decade, aided by philanthropic seed funding and the support of US PREP as a technical assistance (TA) provider. The statewide proliferation of residencies has been accelerated by financial and TA support from the Elementary and Secondary Schools Education Relief (ESSER)–funded Texas COVID Learning Acceleration Supports (TCLAS) grant program in 2021 and by subsequent smaller-scale TEA grant programs and regulatory policy actions. Notably, residencies were highlighted by Governor Greg Abbott’s Teacher Vacancy Task Force as a key strategy for educator training and support.

An initial growth of residencies seeded the ground for TCLAS. In June 2021, the Texas Education Agency approved 15 preexisting residency programs as high-quality residency programs meeting a variety of state standards through the state’s Vetted Teacher Residency (VTR) application—a prerequisite for partnering with districts for the TCLAS grant. These VTR programs had benefited from years of rigorous TA (9 programs as members of the US PREP network) and had addressed the early challenges of implementing a high-quality residency, though most offered unpaid residency slots. They had already built internal systems, funded new positions and hired qualified individuals to fill them, and engaged in shared residency planning and governance with local school districts. With this groundwork in place, vetted EPPs that had seen the benefits of the residency model were able to get a running start on TCLAS grant implementation.

The TCLAS grant program is a set of 10 COVID recovery grant funding opportunities for K–12 school districts. TCLAS Decision 5, the High-Quality, Sustainable Residency Program grant, provided $91 million of funding and TA to districts to support paid teacher residencies, supercharging statewide residency development. Between 2021–22 and 2023–24, the TCLAS residency grant funded more than 85 partnerships, placing more than 2,000 residents across the state. Specifically, the TCLAS residency grant provided a $20,000 stipend for each resident, for up to 20 residents per district, for 3 academic years; an additional $5,000 per resident to be used, at the district’s discretion, for district implementation needs such as mentor teacher stipends; and $50,000 for each host campus to receive state-approved TA to develop a strategic staffing model—a model that reconfigures educator positions to free up funding for resident stipends post-TCLAS.As described by the TEA, “Strategic staffing design focuses on making decisions driven by instructional needs in the district to reallocate underutilized, existing local dollars to fund paid teacher residencies for teacher candidates.” Strategic staffing models took a variety of forms, including residents as substitutes, where residents typically spent 1 day per week substituting for teachers at their school, and residents as paraprofessionals in positions funded by district Title I and II revenue. Other models used residents as tutors, co-teachers, or enrichment leaders. Another goal of the TA funding set-aside was to build a statewide network of trained strategic staffing TA providers at regional Education Service Centers (ESCs), equipped to support districts new to paid residencies both during and after TCLAS.

As the TCLAS residency program was implemented, administrative bodies in Texas enacted policies to define, regulate, and support teacher residencies. The State Board for Educator Certification has undertaken a far-reaching revision of state administrative code, which, among other changes, created a separate, officially recognized residency pathway linked to a new state teaching certificate, the “enhanced standard certificate,” for residency completers.19 Tex. Admin. Code 228.65 § (2024); 19 Tex. Admin. Code 230.39 § (2024). Further support for residencies was included in the recommendations of Governor Abbott’s Teacher Vacancy Task Force, which called on state actors to both establish and fund a teacher residency pathway. At the same time, the TEA has continued running smaller-scale grant programs to fund sustainable residencies and expand uptake of the model to new districts.Grants include the 2023–2025 Texas Strategic Staffing Grant for Sustainable, Paid Teacher Residency Program; 2024–2025 Sustainable Residency Continuation Grant; and 2024–2026 Texas Strategic Staffing ESC Direct Grant.

The Benefits of the Residency Model

The seeding of additional vetted residency programs through TCLAS and beyond has been successful. The number of Vetted Teacher Residency providers in the state substantially increased from the initial 15 EPPs in 2021 to 37 before the 2023–24 school year. At the start of the 2024–25 school year, 30% of all EPPs in the state offered a vetted residency program.37 EPPs out of 120 total EPPs in Texas, according to the TEA Educator Preparation Programs dashboard: https://tea-texas.maps.arcgis.com/apps/dashboards/8fdeed6e29b741ba8bac151ac023186d (accessed 11/04/24). Of these, most are 4-year colleges and universities; the list also includes community colleges, ESCs, a graduate school of education, and one other nonprofit provider.

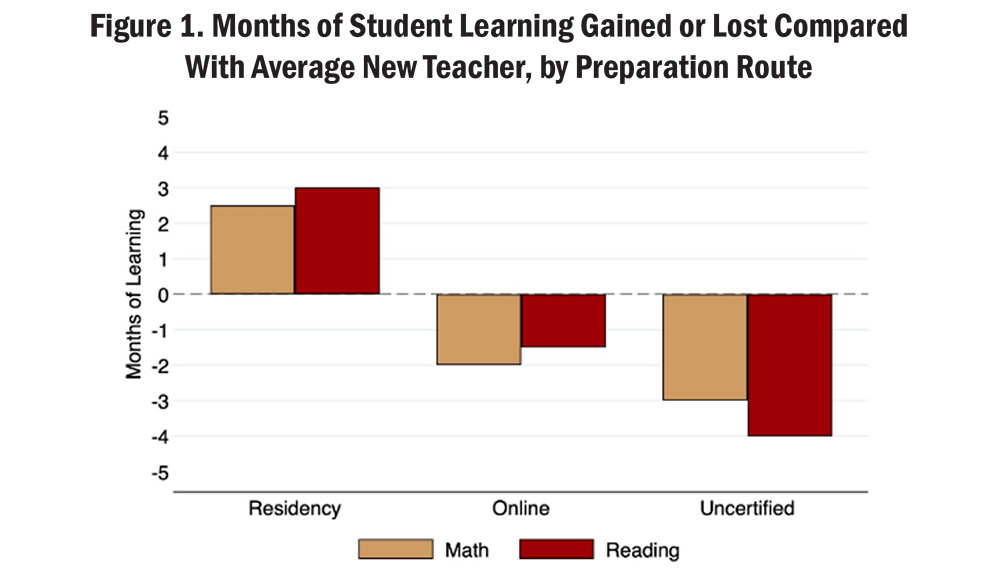

The establishment of paid teacher residency programs across the state has helped to expand access to the teaching profession via residency stipends, improve teacher preparation, increase teacher retention,Kirksey, J. J. (2024). Building a stronger teacher workforce: Insights from studies on Texas teacher preparation [Brief]. Texas Tech University Center for Innovative Research in Change, Leadership, and Education. https://hdl.handle.net/

2346/99592 and improve student outcomes. According to Texas-based research, students of teachers prepared through a residency show, on average, 2.5 months of additional learning gains in math and 3 additional months in reading compared to students of an average new teacher.Kirksey, J. J. (2024). Building a stronger teacher workforce: Insights from studies on Texas teacher preparation [Brief]. Texas Tech University Center for Innovative Research in Change, Leadership, and Education. https://hdl.handle.net/2346/99592 The research found even larger differences in learning gains relative to the online-prepared and uncertified teachers who now make up a majority of new entrants into the Texas teacher workforce (Figure 1).

To better understand the elements of residency implementation that have led to these improved student outcomes, the Learning Policy Institute conducted two studies on teacher residency implementation in Texas in 2023 and 2024 that included interviews with EPP and partner district leaders, faculty, and staff, as well as with teacher candidates and program completers. Analysis across these interviewees revealed near-universal enthusiasm for the residency model due to the numerous benefits it confers on residents themselves as well as their mentor teachers, partner schools and districts, and educator preparation programs.

Benefits for the Resident

The clinically intensive, practice-based residency training is rigorous and thorough, preparing candidates for the classroom in a manner that interviewees described as superior to other pathways with shorter clinical experiences. High-expectation, high-support coaching and observation cycles have provided deeper learning opportunities for residents. Recent graduates characterize their teacher preparation experience as a challenging but worthwhile investment. The paid element of residencies enables candidates to engage in the full range of a teacher’s professional responsibilities (e.g., participating in parent conferences, professional development, and team planning), all while taking teacher preparation courses, by easing their financial burdens. Stipends also expand access to residencies for teacher candidates who would otherwise be financially unable to commit to clinical teaching, increasing the size and the racial and socioeconomic diversity of the applicant pool.

Educator Perspectives on Benefits for Residency-Trained Teachers

Rigor of Residency Training and Resulting Preparation for the Classroom

Now I know how to teach the student. I know how to assess the student. I know how to [identify] a student’s weakness and improve it. I know how to improve my instruction. I know how to set [up] classroom management. I know how to build a relationship with the student.

– Teacher resident, urban West Texas

I have these two [teachers] that just came out of the residency program, and they’re at a totally different level than brand-new teachers … they’re so prepared. I have never met teachers [who are] brand-new, [who are] this prepared for the classroom. … Right now they’re two of my best teachers.

– Principal, suburban West Texas

Our May graduates, every single one of them, had a job before they crossed the stage. … We graduated, I don’t know, close to 100, and every single one of them had a signed contract before they crossed the stage.

– EPP faculty member, rural North Texas

The resident is not a visitor on campus. When the resident feels like they belong to the campus, they’re part of the district, [and] it makes such a difference. It shifts the mindset from “I’m a university student visiting a classroom,” to “This is my classroom. These are my students, and I’m responsible for them.” ... That personal investment translates into a willingness to be a better teacher, a willingness to receive feedback even when it’s uncomfortable, and a willingness to try new things.

– US PREP technical assistance provider, South Texas

Importance of Residency Stipends

I could definitely see a difference between my experience versus [my cousin’s, who did not complete a paid residency]. For her, she would do a full day [of clinical teaching] for free, and then she would still have to go home, finish any homework or assignments, and then she would also have to go to work. So, I felt really grateful that I didn’t have to worry about that. I didn’t have to worry about, “How am I going to pay my next bill? What shift do I need to pick up?”

– Residency graduate, rural South Texas

[It was] a life-changing thing [for our residents] to be able to get that TCLAS money. ... It’s a deal-breaker for a lot of nontraditional students to do a yearlong residency with no pay.

– EPP faculty member, suburban North Texas

Benefits for Partner Schools and Districts

The TCLAS residency grant was designed to establish sustainable teacher pipelines, reduce attrition, and improve student access to well-qualified teachers. Residencies have positively altered district hiring practices: Administrators in residency districts know their applicants’ abilities after what has amounted to a yearlong interview. District and school administrators also value hiring first-year teachers who already have experience with the local context and who perform like their more experienced counterparts. Indeed, some districts have restructured their recruiting and hiring practices to attract residents as their top-choice candidates. Districts have also built robust working relationships with their partner EPPs, drawing on shared program governance structures, to jointly assess resident performance and make programmatic decisions.

Residencies confer additional benefits to mentor teachers and their students. Having a second educator in the room enables more differentiated and individualized instruction. Mentor teachers also reported learning new concepts and pedagogical strategies from the residents, such as ideas for introducing material, small group reteaching, or enrichment. Further, being a mentor teacher can be an important step on a career ladder for experienced teachers looking to move into instructional coaching, administration, or clinical university faculty positions.

Educator Perspectives on Residency Benefits for Schools and Districts

Residencies Creating Pipelines of Well-Prepared Candidates

I felt comfortable as a campus principal hiring someone from within this pipeline, because again, you get to see their work ethic. You get to see how they collaborate with their peers. You get to see how they interact with parents.

– Principal, suburban South Texas

[Because residency completers know how] to be in a classroom and to be effective right out of the gate, we were so interested in trying to retain them that we came up with a letter of assurance for next year, for a job. … We don’t want to let you go because you’re just that top-notch. We want to retain you.

– Superintendent, suburban North Texas

It’s really a game changer to get these [teacher residents]. … And when you hire them, you don’t get a first-year teacher. You get, really, a veteran teacher that has relationships with individuals on that campus, has relationships with the students. They understand the culture. They understand … the expectations. It’s really just a win-win on behalf of the school district.

– Superintendent, suburban North Texas

The principal wants those residents ... to stay on that campus. So, they’re going to be really invested and ensure that resident is growing to meet the needs of their students and … be a part of that community.

– Education Service Center TA provider, North Texas

Strengthened Partnerships With Educator Preparation Programs

I think [our partner EPP’s] willingness to just kind of share really anything—data, resources, or time—I think it goes a long way. … When we go back to our directors and our superintendents and tell our district leaders what we’re doing [and] how they’re supporting us, it makes them supportive of the partnership too.

– District administrator, rural Gulf Coast region

Instructional Advantages

It’s just like having a whole other teacher in there. … She knows the classroom management. She knows the kids very well. She knows their parents. She knows what’s expected.

– Mentor teacher, rural North Texas

Benefits for Educator Preparation Programs

Another outcome of the TCLAS investment was a changed culture and processes within EPPs for continuous improvement based on data, resulting in increasingly strengthened preparation programs. Further, in sharing governance with district partners, EPPs showed their institutions’ commitment to addressing local teacher pipeline issues and strengthened their relationships with local schools and districts—a key criterion to ensure sustainability of the residency partnerships.

Perspectives on Residency Benefits for Educator Preparation Programs

Continuous Improvement Within the EPP

We all feel really strongly invested in the program. So, if we see something that we feel like we can improve, we don’t have any qualms with just emailing and saying, “Hey, let’s all get on the same page.” Nobody needs to come down from the top, telling us we’ve got to do that.

– EPP faculty member, urban Gulf Coast region

We showed [our faculty] a video of students teaching during their observations. The respective faculty of the courses they’re teaching [realize], “Oh my gosh, my students are not getting this, so I need to do a better job in aligning or lesson planning.” So they change, they make improvements to the syllabus so that they will be aligned to where the students are.

– EPP faculty member, urban West Texas

Strengthened Collaboration With District Partners

Innovation doesn’t happen in silos. It’s happening because [EPPs and districts] are now talking. Strategic staffing might have been a starting point, but look how many … innovative ideas have morphed as a result of these conversations, which is what we want to happen … and I think that’s what’s happening with this partnership. They’re thinking outside the box.

– US PREP strategic staffing TA provider, rural Gulf Coast region

[We’re trying] to build a program on the ground that’s built on building relationships, trust, and efficacy—actual tight-knitted rollout that is co-designed and mapped together. ... [We] say, “So let me understand the things that are important to you [at the district]. Here are some things that we [at the EPP] think are important as well. How do we work these in together?”

– EPP dean, urban West Texas

Factors Supporting Effective Residencies: Progress and Needs

Our analysis of Texas’s investment in residency programs reveals multiple ways that the state enabled successful implementation, as well as opportunities for continued problem-solving, such as:

- Establishing a residency requires implementation support to bring new practices to scale within an EPP and its district partners. The US PREP process to transform its network EPPs into full residency models takes 4 years, and these EPPs often continue to refine their models beyond this initial period. Building TCLAS residency planning and implementation on existing transformation efforts was a well-informed state decision and strongly suggests the need for ongoing support to establish sustainable paid residencies in entirely new settings.

- Sustaining funding for resident stipends is important for ongoing recruitment. Providing TA for districts to adopt strategic staffing models, as TCLAS did, will contribute to the continuity of these effective residencies. Interviewees consistently spoke highly of strategic staffing TA, regardless of whether the TA was provided by US PREP or an ESC, which can be attributed to open and frequent communication between the providers. As a district administrator explained, “I don’t think we could have thought through all the intricacies of it without someone guiding us.” Due to the TA, some districts will be able to continue $20,000 resident stipends via strategic staffing strategies. However, other districts provided lower predictions for post-TCLAS stipends, ranging from $5,000 to $12,500 per resident—amounts less likely to successfully attract teacher candidates who would need to forgo outside employment. Higher stipends were associated with larger urban districts and lower stipends with smaller rural districts. Overall, however, districts remained dedicated to residency sustainability, aiming to identify and combine funds from other sources with funds made available through strategic staffing.

- Strong EPP–district partnerships have been key to residency success. In designing TCLAS requirements, the state recognized the need to bridge long-standing silos between preparation and practice. To this end, TCLAS districts and partner EPPs were required to follow structured approaches to shared governance, including at least three meetings annually to analyze teacher resident data and design a strategic staffing model. These structured processes strongly influenced the workings of residency partnerships. One district administrator explained that “having those governance meetings and being able to have ... that district–EPP relationship [has been] the true key to success.” In some cases, EPPs also convened neighboring districts to collaborate on developing the local residency pipeline—for example, by securing agreements from each district to equalize the stipend amount and benefits that residents receive.

- Since TCLAS funding has expired, smaller grant programs offered by TEA have not been sufficient to meet demand. As more districts see the benefits of hosting residents, momentum to build new residency programs has continued to grow. However, the smaller, competitive grant programs developed as follow-ons to TCLAS have had more applications than awardees.See, e.g., Texas Education Agency. (2024). 2024–2026 Texas Strategic Staffing Grant for Sustainable, Paid Teacher Residency Program. https://tea.texas.gov/finance-and-grants/grants/grants-administration/grants-awarded/2024-2026-texas-strategic-staffing-grant/2024-2026-texas-strategic-staffing-grant-for-sustainable-paid-teacher-residency-program Given the promise of residencies for strengthening the Texas teacher workforce, additional start-up support for new district–EPP residency partnerships is warranted.

Policy Recommendations

Residencies produce more effective teachers who tend to stay at higher rates, saving money for districts and the state.Learning Policy Institute. (2024). 2024 update: What’s the cost of teacher turnover? [Interactive tool]. https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/2024-whats-cost-teacher-turnover; Saunders, R., Fitz, J., DiNapoli, M. A., Jr., & Kini, T. (2024). Teacher residencies: State and federal policy to support comprehensive teacher preparation. Learning Policy Institute & EdPrepLab. https://doi.org/10.54300/358.825 The TCLAS residency program was a promising start toward building robust statewide teacher pipelines and improving access to well-qualified teachers for all students. However, if residencies are to train teachers in quantities that supplant teachers trained through high-turnover, low-quality pathways, residencies need to become far more common—that is, an option for all districts that want to host them—which will require state-level support. Several elements of residency implementation need to be resourced, including resident and mentor teacher stipends—especially in rural and high-poverty districts—and technical assistance to support districts in developing strategic staffing models. Policymakers who want to support residencies can do the following:

- Provide initial state support for resident and mentor teacher stipends in new residency programs and matching grants for residency stipends in districts with existing residencies. The combination of TCLAS grant requirements and the use of strategic staffing was necessary for moving districts and their EPP partners toward sustainably funded residency stipends but was not entirely sufficient. Progress was uneven, with many districts either unable to continue paying residents at the $20,000 per year level or having to decrease the number of residents they host. Mentor stipends also appear to have decreased post-TCLAS. Dedicating state funding to combine with local strategic staffing could help maintain TCLAS funding levels. State funding could partially subsidize $20,000 resident stipends. An additional $5,000 per resident per year could be used for district implementation needs, including mentor teacher stipends. For example, a 1:1 or 1:2 state-to-district matching grant could taper off over time or as dictated by ongoing district needs.

- Provide targeted financial support for residency costs in rural and high-poverty districts. Districts facing sustainability challenges for paid residency implementation tended to be smaller and located in more rural areas than districts that were able to sustain residency stipends at the $20,000 TCLAS level. Residents in rural contexts also expressed a greater need for offset transportation costs for longer commutes. A related issue is that teacher shortages in Texas are more common for campuses serving high-need areas, including rural areas. Given these realities, new funding to support residencies may productively draw on previous state-level legislation, which defined a formula to target high-need districts through the Texas Teacher Incentive Allotment (TIA) program. This formula can serve as a reference point to prioritize stipend support where it is most needed.

- Build on the new “enhanced standard certificate” to provide financial incentives for residency completers. Many prospective teachers choose the uncertified or intern routes despite these routes’ less rigorous training and poorer outcomes because individuals in these positions can be paid as teachers while learning on the job. Since one aim of residency pathway expansion is to draw prospective educators toward a higher-quality training option, policymakers can consider ways to incentivize this up-front investment by allowing a year of salary-step credit for residents’ clinical year, which has implications for a new teacher’s initial salary and creditable years of service toward retirement. Some districts already offer this benefit for their residents. Similarly, some TIA districts have recruited residency completers by compensating them at the “recognized” level. The legislature could consider codifying this strategy statewide. Directing funds to offset residents’ certification exam costs, including prep materials, would also be a worthy investment.

- Provide seed funding to regional Education Service Centers for strategic staffing technical assistance for districts building new residency programs. As part of TCLAS, US PREP trained ESCs on strategic staffing models so that they could pass this training on to districts both during TCLAS (funded by a $50,000-per-district TCLAS set-aside for ESCs) and after TCLAS (funded by TEA at $70,000 to $80,000 per district in small-scale TCLAS follow-up grants). For the districts that did not receive these grants, the ESCs’ post-TCLAS fee-for-service arrangement disincentivizes new district uptake. Our research suggests that new districts became interested in residencies once they saw the benefits firsthand—for example, by hiring residency alumni—which suggests that more districts will gain interest as more residency graduates join the workforce. Districts new to residencies will benefit from an equivalent in-kind seed grant to their regional ESCs for strategic staffing TA to encourage continued proliferation of high-quality residencies.

Other considerations from the research apply directly to state agencies and boards, including needed infrastructure to support statewide residency expansion. Currently, some districts are sustaining paid residences in part with external funding, such as higher education grants, state and federal formula funding, or registered teacher apprenticeships. TA for districts on accessing and braiding funding could smooth this process, especially for smaller districts with less infrastructure to apply for grants. The state could also consider establishing regional residency consortia through the ESCs. Some districts already collaborate on equalizing stipends for residents. A meaningful next step may be to support regional collaboration on hiring residency alumni. For example, districts could share the cost of resident stipends or develop a reimbursement agreement for residents who choose to work in a district neighboring the one where they trained, which would allow the training district to avoid losing the return on their investment.

Conclusion

Texas has made compelling progress in seeding, sustaining, and scaling paid teacher residencies as a research-based strategy to incentivize high-quality teacher training, reduce turnover, and improve student learning. District and EPP administrators, faculty, and staff, as well as teacher residents and residency completers from across the state, shared glowing assessments of residencies. To continue this momentum, state policymakers can provide targeted supports to residents, districts, and EPPs to sustain and scale current residency participation and maintain the infrastructure necessary to build new programs.

Investing in Teacher Residencies: Sustaining Texas’s Momentum to Prepare High-Quality Teachers (brief) by Kimberlee Ralph and Jennifer A. Bland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Core operating support for the Learning Policy Institute is provided by the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Raikes Foundation, Sandler Foundation, Skyline Foundation, and MacKenzie Scott. The ideas voiced here are those of the authors and not those of our funders.