The Road to Recovery in Learning: How California Points the Way

This post was originally published on December 6, 2022 by Forbes, and is part of LPI's Learning in the Time of COVID-19 blog series, which explores strategies and investments to address the current crisis and build long-term systems capacity.

Across the nation last week, many families gathered and gave thanks for what appears to be the beginning of the end of the COVID-19 pandemic that has kept us apart for the past 2.5 years. We now appear to be in an “endemic” stage that, with caution and vaccinations, has allowed us to return to many normal activities.

But in education, it’s clear we can’t return to the old normal—the condition we were in when schools closed their doors in March 2020. Throughout the country, profound and long-standing inequalities were highlighted the moment schooling became remote: It became apparent that students from low-income families not only often had little access to computers and connectivity to use for distance learning, and their schools were often the least well-staffed and resourced to provide the tools and supports needed. Moreover, families in low-income communities and communities of color were most likely to experience illness and unemployment, along with food and housing insecurity.

Since school doors have reopened, educators have struggled to address student trauma and learning lags, as well as shortages of teachers, bus drivers, substitute teachers, and others—shortages that emerged with COVID-19 surges and quarantines and have continued with mass retirements and resignations.

The effects of these challenges were made clear a few weeks ago when the 2022 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) results were released. Called “the nation’s report card,” NAEP tests a sample of 4th- and 8th-grade students in every state in math and reading every other year, looking comparably at achievement over time. Because the test was put on hold during the pandemic, the release marked the first national results since 2019.

The results pointed both to our challenges and to some unexpected bright spots that highlight opportunities for creating a new normal in public education. As anticipated, the current cohort of 4th- and 8th-grade students scored noticeably lower, on average, than students in those grade levels in 2019. U.S. Secretary of Education Dr. Miguel Cardona called the results “appalling, unacceptable, and a reminder of the impact that this pandemic has had on our learners.” Dr. Peggy Carr, Commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), which issued the report, described the results as “almost 2 decades of educational progress washed away.”

An additional analysis by researchers at Stanford and Harvard linked these data to state testing data in every district across the country, finding that the average U.S. public school student in grades 3–8 lagged students in 2019 by the equivalent of a half year of learning in math and a quarter of a year in reading. Test scores generally declined more in school districts serving students from lower-income families than in those serving more affluent families. The extent to which a school district returned to in-person learning sooner turned out to be only a minor factor in the change in student performance, the researchers found—a point reinforced by the NCES when it released its findings.

However, there were exceptions to the rule: Learning held steady or moved forward in some districts serving children from low-income families in highly impacted communities. California, where I currently serve as president of the State Board of Education, illustrated part of that story in ways that may inform what the new normal should look like.

Although California is the most diverse state in the nation and among those with the highest student poverty levels—78% of students in California’s public schools are students of color and 62% are from low-income families—students lost less ground than those in most states in both math and reading, and in the key area of 8th-grade reading, California students showed no learning decrease at all.

As a result, the state moved up in NAEP’s state-by-state rankings in all areas. In 8th-grade reading, California moved from 48th in 2013—at the very bottom of the state rankings before its more equitable new funding formula was installed—to 38th by 2019, and it reached the national average in 2022.

Among cities, both Los Angeles Unified School District and San Diego Unified School District were part of the NAEP Trial Urban District Assessment (or TUDA). Not only did both cities’ districts do better than most other cities and the urban average—which dipped by several points across the nation—but Los Angeles actually gained slightly in 4th-grade reading and significantly in 8th grade reading, while San Diego remained the top-scoring urban district in the nation in 8th grade reading, and its scores stayed stable and in the top group of cities in 4th grade reading.

This is not to minimize the extensive work that is still needed for recovery and further progress. And while losses were less than in other states, math scores fell more than those in reading. But I think there are some important takeaways from the NAEP results.

The first is that California’s swift and comprehensive actions from the very minute COVID-19 was discovered in the state appear to have paid off. Since the earliest days of the pandemic, California has invested nearly $24 billion to both ensure the safety of students and teachers and provide intensive supports to keep students learning.

These all-hands-on-deck efforts have left no aspect of education untouched, including:

- bridging the digital divide to dramatically close the gap in access to computers and connectivity, which is now nearly closed;

- focusing on learning support from the beginning and offering digital integration guidance with extensive professional development for teachers;

- immediately providing free personal protective equipment (PPE), free COVID-19 testing, and free vaccination clinics in schools, and upgrading HVAC systems, so that California had, by far, the fewest school closings per capita in the nation last year;

- funding after-school and summer learning with investments sufficient to support summer school in 9 out of 10 districts in the past 2 years;

- intensifying social-emotional and mental health supports;

- expanding community schools that provide wraparound services to ensure that students are supported with nutrition, health services, and social services;

- bringing in tutors and literacy coaches; and

- investing $3 billion in teacher recruitment and retention through service scholarships, supports for preparation and mentoring, and new program models like teacher residencies.

Los Angeles, for example, did all of these things: using state and federal funds and initially dipping into its own reserves to ensure that students got food, computers, and hot spots immediately upon school site closing; offering universal summer school and tutoring for the past 3 years; and expanding mental health supports and community schools initiatives. Los Angeles was also able to open school with all of its vacancies filled this year, while many districts were experiencing severe shortages, in part because it was one of the first districts to offer substantial wage hikes and retention bonuses last year while recruiting aggressively and reaping the benefits of its several teacher residency programs that produced a well-prepared supply of teachers in shortage areas who have been staying in the classroom. Los Angeles also put in place a coherent plan to support reading—both in the lower grades, with systematic instruction and English language development supports, and in the middle schools, with an interdisciplinary approach that infused literacy into every subject area—giving its students the opportunity to continue to develop their reading and writing skills throughout the grades.

Oakland Unified School District was among other districts serving students from low-income families that gained ground in English language arts during the pandemic and lost less ground than others in math. The district found that its long-standing commitment to community schools offering wraparound services and wide-ranging connections with community-based organizations was a huge assist in supporting children and families in multiple ways during the pandemic. With a focus on “joyful schools” supporting health and mental health services and restorative justice programs, along with expanded learning time after school and in the summer, there were many opportunities to help students regain traction when they returned. The district had also adopted strong foundational literacy programs along with the culturally relevant and engaging EL Education literacy curriculum for standards-based instruction connected to social-emotional learning. After-school providers provided aligned literacy supports to which high-dosage tutoring and small-group instruction were added for both literacy and numeracy.

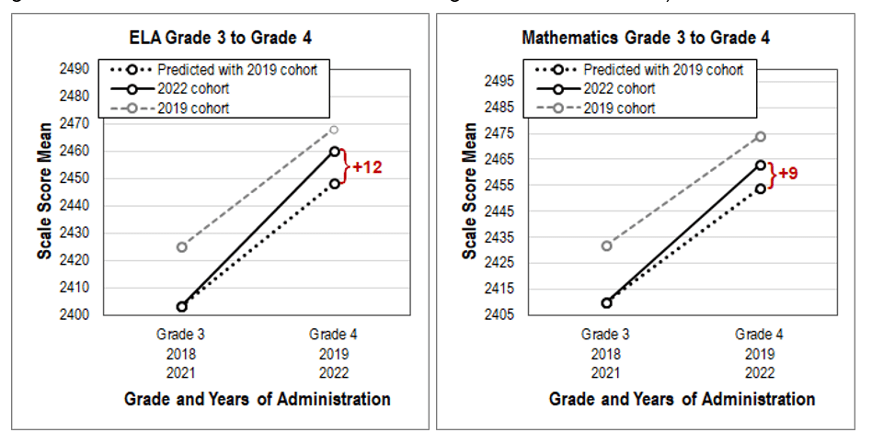

These hopeful signs on the NAEP assessments were reinforced by state test results showing evidence that students who took the Smarter Balanced test in both 2021 and 2022 experienced steeper learning gains in most grade levels than in the years before the pandemic. (See table below showing 4th-grade growth in English language arts and math, for example.) If students continue to learn at this accelerated pace, they will not only close the gaps with prior cohorts, but will move ahead of them in the years to come.

This learning acceleration suggests a path to a new normal that supports greater success for students. This path will require ongoing strategic investments in what we know substantially improves the quality of education.

In California, Governor Gavin Newsom and the state legislature began to transform the public education system 3 years ago as they increased school spending by more than 30% while redesigning schools to meet 21st-century needs. This has included substantially increasing investments in the school funding formula that allocates base funding equitably based on pupil needs; adding a full year of preschool for all 4-year-olds; investing in health care and mental health care for children and youth; providing expanded learning time after school and in the summer; launching community schools that offer wraparound services and enriched learning in high-poverty communities; and incentivizing new models of high school education to prepare students for college, career, and civic readiness in today’s society.

It also includes continuing to ensure that all students have the technology and connectivity to take advantage of learning resources that support their skill recovery; continuing to invest in academic supports that are effective in improving student achievement, such as high-intensity tutoring programs, academic summer learning programs, and school-based literacy coaches; and providing ongoing support for teacher preparation, professional learning, and retention so that talented individuals choose teaching and stay in the profession—another evidence-based key to strong achievement.

The recent data on student achievement show that maintaining a deep commitment to the academic progress of every student must continue in full force in the days, months, and years to come. This means investing in high-quality teachers who offer rigorous and relevant instruction in every school; expanding learning time effectively; and supporting a whole child, whole school, whole community approach that enables learning for all. As a state, and as a nation, we cannot take our foot off the accelerator now.