More Guns in Schools Is Not the Answer to School Shootings

This post was originally published on June 2, 2022 on Forbes.

Update: Congress Passes Bill to Reduce Gun Violence

On Friday, June 24, Congress passed a bill to increase gun safety and protect schools from mass shootings that have recurred again and again, most recently in Uvalde, Texas. The bill includes increased funding for mental health and student supports in schools, along with incentives for states to enact “red-flag” laws, and additional scrutiny of gun buyers under the age of 21. States and districts can allocate the additional funds designed to support safe and just learning environments toward the evidence-based strategies examined in this blog. Research suggests these strategies are likely to be effective, while school “hardening” that includes greater police presence is likely to increase gun casualties, rather than reducing them.

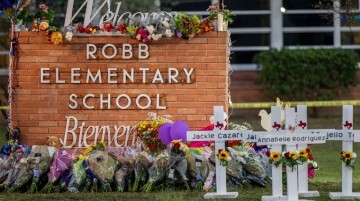

Since the horrific shooting that killed 19 children and 2 adults at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas—the 27th school shooting so far in 2022—there have been at least 15 other mass shootings in the United States, 12 of them over the Memorial Day weekend.

According to the non-profit Gun Violence Archive, there have already been more than 200 incidents in 2022 in which four or more people were shot or killed.

And according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, firearms are now the leading cause of death for children under age 18 in the United States. Many of these incidents were unintended shootings of children by other children who had found a gun in a relative’s home.

A number of politicians have called, once again, for arming teachers in schools and increasing the presence of police or security officers. This is despite the facts that teachers do not want this responsibility and security officers at Robb Elementary were unable to prevent the shooting.

These so-called solutions are badly misguided. A recent study of every intentional school shooting from 1980 to 2019 found that there was no relationship between having an armed officer on the school grounds and the rate of injuries. Furthermore, after controlling for the school region, type, grade level, location, use of lockdown drills, number of and type of weapons and shooters, there were nearly 3 times as many casualties in incidents with armed officers present. The authors concluded that “an armed officer on the scene was the number one factor associated with increased casualties.”

As J. Thomas Manger, former president of the Major Cities Chiefs Association cautioned, “The more guns that are coming into the equation, the more volatility and the more risk there is of somebody getting hurt.” And, indeed, guns in schools have proved to be dangerous. Aside from shooters coming onto school grounds, in 2022 there have already been at least 85 incidents of gunfire at schools, resulting in 36 deaths and 52 injuries nationally.

Guns in schools can easily find their way into the hands of students. There are many reported cases of guns misplaced when they were allowed in schools: guns left in bathrooms, locker rooms, or sporting events, and even an incident in which a gun fell out of a teacher’s pocket while they did a backflip. Some of these guns were later found in the hands of students. There have also been multiple incidents in which guns were accidentally discharged at schools by school resource officers or teachers, as well as events in which guns were deliberately fired. These include multiple firearm suicides by faculty or staff at schools; a janitor who killed two of his colleagues at a performing arts school in Florida; and a Spanish teacher who was fired and then returned to school with an AK-47 in a guitar case. He used the gun to kill the school headmaster and then himself.

Imagine the dangers of having to keep guns available in school, loaded or with ammunition nearby, to be ready in the seconds available in an emergency. We would then likely have to add schools to the places where unintentional shootings by children and youth occur, worry about angry or suicidal young people getting hold of the guns made more accessible by their presence in schools, and experience the predictable agony of children caught in the crossfire between shooters and their own teachers.

The situation at Uvalde confirms, yet again, at least three necessary approaches to stop school shootings: gun controls, reporting of warning signs, and school-based social-emotional and mental health supports.

In the Uvalde shooting, the tragedy followed a familiar form.

Salvador Ramos, the 18-year-old who went on a rampage with an AR-15 rifle, was a troubled young man, who attended the local high school until he dropped out. According to news reports, he had had a speech impediment since childhood and had been bullied throughout school. He had a challenging home life with his mother and had already begun missing school before moving in with his grandmother. Ramos developed a violent online presence. He reportedly threatened rape and murder on multiple occasions, posted pictures of his rifles, and expressly noted that he planned to “shoot an elementary school.”

The semiautomatic, self-loading assault rifle Ramos used to kill 21 people was also the type of weapon used for 11 other mass shootings in the last decade. When assault weapons are used in mass shootings, they have resulted in far more deaths and injuries, with 6 times as many people shot per incident as when non-assault weapons were used. A study comparing the years in which the federal assault weapons prohibition was in effect (1994–2004) to the years before and after the prohibition estimated that the ban would have prevented more than three-quarters of the mass shooting deaths that occurred when it was not in effect. A growing body of research shows that states that have limited access to assault weapons and high-capacity magazines experience far fewer mass shootings and far fewer injuries and deaths.

The many threats Ramos made and plans he discussed with acquaintances and online are also common, having occurred in more than half (56%) of mass shootings and in 77% of school shootings. These warning signs present opportunities for intervention that could save lives. Extreme Risk laws, now enacted in 19 states (not including Texas) are one such opportunity. Sometimes known as “red flag” laws, these laws empower those who recognize warning signs to petition a court to temporarily restrict a person’s access to firearms when they pose a significant risk of using them to cause harm, saving lives in the process.

The fact that Ramos had attended school in Uvalde and had been bullied in school as a child is also common among school shooters. Indeed, more than 90% of school shootings have been perpetrated by current or former students, and 87% of school shooting perpetrators left behind evidence that they were victims of severe bullying within the school.

It is quite possible that the shooting at Robb Elementary was a preventable tragedy. Prevention might have come in the form of gun control laws, a more appropriate police response to reported dangerous and threatening behavior from a former student, or more accessible mental health services coupled with stronger, more positive relationships between Ramos and other young people and adults in the school.

A young man who lived across the street from Ramos and tried to befriend him at an earlier time cried when he heard the news about the shooting, and put it succinctly: “I think he needed mental help. And more closure with his family. And love.”

Ironically, key approaches that might have helped Ramos in school were represented in Obama-era guidance on school discipline that was repealed by the Trump Administration. This non-binding resource, created to help schools reduce exclusionary discipline strategies like suspension and expulsion, offered information about initiatives that help students develop social and emotional skills and receive mental health supports, so they can understand and manage their feelings (including anger, rejection, and frustration), and learn how to resolve conflicts peaceably.

These social-emotional learning initiatives have been found in hundreds of studies to reduce negative behavior and violence in schools, making schools safer, while also increasing graduation rates and academic achievement. The guidance builds on what we know about how to increase school safety through “conflict resolution, restorative practices, counseling and structured systems of positive interventions.” The guidance also provides research-based resources to address students’ mental health needs, as well as proven practices that make students feel more connected to school and part of a community—so they are less likely to engage in negative and harmful behavior.

It is clearly time for America to come to its senses about gun violence in our society and safety in our schools. The U.S. has less than 5% of the world’s population, but represents 46% of the world’s civilian-owned guns has 31% of the world’s mass shooters; and has gun homicide rates that are 25 times higher than those of other high-income countries. Clearly it is time for sensible laws that keep assault weapons out of the hands of civilians and weapons of any kind out of the hands of those who pose known risks to themselves and others.

And in our schools, we need to continue the work done by many states that are pursuing educative and restorative approaches to school safety and student success by leveraging initiatives that strengthen students’ social-emotional skills, mental health supports, and sense of safety and belonging. If we genuinely want to ensure safer schools, we should follow the evidence about what works, rather than jeopardizing more lives with more guns where they clearly do not belong.

Photo by Brandon Bell/Getty Images