Deeper Learning: An Essential Component of Equity

Q&A on Deeper Learning + Equity

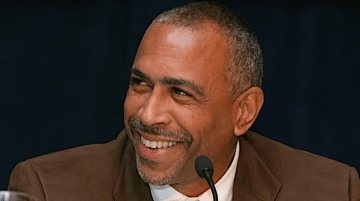

With Dr. Pedro A. Noguera

Dr. Pedro A. Noguera is a Distinguished Professor of Education at the Graduate School of Education and Information Studies at UCLA, where he founded the Center for the Transformation of Schools (CTS). We sat down with Dr. Noguera, author of Taking Deeper Learning to Scale, to discuss the role of deeper learning in providing all students with an equitable and empowering education and what it will take to “scale up” deeper learning practices.

Often, when people think about equity, they think about allocation of resources. Why is access to deeper learning also a critical equity issue?

We’ve known for a long time, thanks to Jeannie Oakes and her work on the tracking of students, that kids who are seen as less able or “not college material” are often in classes that don’t challenge them. Because we assume that kids who are in need of remediation are not smart, these students are left doing low-level work that doesn’t tap into their higher order thinking skills. This is a false assumption that exacerbates the equity issue because what it often means is that these students aren’t being challenged and encouraged to think deeply, and they are not developing the skills they are going to need for college and for work. This is the primary equity issue. It is as important as whether or not they are in a school with adequate resources, because if they are in a classroom where they are not really learning much, it is going to impact their education and their long-term outcomes.

How do we support schools and districts to build their capacity to support deeper learning?

In part, we have to provide very clear models. We also have to challenge beliefs, which can be a huge obstacle. It is often helpful to give examples of places where deeper learning is happening, so you can show educators that it’s not just a theory that has been hatched in the university, but it actually is working in many places. And then you have to give guidance to the educators—the teachers and the people who lead the teachers—on what kinds of learning activities elicit deeper learning. It can’t be an abstract conversation. It has to be connected to the work that schools do. In many districts, professional development is ineffective because it isn’t connected to practice.

In your report for LPI, Taking Deeper Learning to Scale, you highlight the example of Brockton High School, which has made deeper learning practices the norm for most teachers and students. What’s special about the Brockton High School story?

So much of the Brockton story is about teacher leadership. In order to prepare students for high-stakes exams, the Brockton teachers chose to implement a “literacy across the curriculum” strategy. That meant not just teaching students to read and write, but teaching them to develop their ideas and arguments, because those were the skills students were expected to demonstrate on the state exam. Rather than starting with a whole-school strategy, the strategy was to work with “the willing,” and then to build from there. In the first year of the Literacy Initiative, the failure rate on the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS) was reduced by half, and the proficiency rate doubled. The second year showed similar results. Of the 2008 graduates, 97% went on to higher education, and 47% were accepted at 4-year colleges. In 2009, 98% of Brockton’s seniors passed the mathematics and English exam by graduation; 78% of its 10th-grade students achieved either advanced or proficient levels in English Language Arts (matching the state percentage); and 60% of 10th-graders achieved similar levels in mathematics. As their efforts showed success, the teachers were able to get more buy-in from the faculty and reach “critical mass.”

What are the school design considerations that promote and support deeper learning?

Collaboration time is key, so you need a school schedule that enables teachers to work together during the day. You also need sufficient class time for students to engage in more complex tasks. Think about how much time students are sitting passively at school. They’re sitting and listening or taking notes, but what’s the evidence that they’re learning? The path to higher achievement is through engagement, but engagement is multidimensional. It’s not simply about whether the kids are present and doing the work; that’s the behavioral part. But there’s also the cognitive part—how deeply do they understand the work? How much can they connect what they’re doing on one project to other things they’ve learned or to what they’ll have to learn next? And third, there’s the emotional part. How much do they actually care about what they’re doing? How invested are they? We all work harder when we have a passion for what we’re doing.

What’s the relationship between evidence/assessments and deeper learning?

In classrooms and schools focused on deeper learning, teachers are constantly looking for the evidence that students are learning, and students are constantly looking for their own evidence of learning. That orientation makes the classroom a totally different place. It becomes a working place, not a listening place. When teachers teach with a focus on the evidence of learning, they teach differently. They teach like a coach or a music teacher, because they’re constantly looking at the student and asking, “Am I getting through? Am I reaching the student? What does his or her work show?”

Nationally, we’re in a period of flux. High-stakes assessments were drivers with No Child Left Behind. The Every Student Succeeds Act of 2015 provides more flexibility for states to select assessments that will allow and encourage deeper learning. Schools and districts that are adopting performance assessments understand that assessments are a tool to support learning. This is promising work.

Educators and their community partners are increasingly looking at community schools as an evidence-based strategy to support the broad range of student needs. How can the community schools model support deeper learning goals?

Students from low-income families have a vast array of non-academic needs that impact learning. It’s essential that schools have services and personnel to address those needs. Students who have experienced trauma, who are homeless, or who are experiencing other forms of instability in their lives aren’t going to do well academically—not because they can’t, but because they have needs that impact their ability to learn. These needs are understood and addressed in community schools, like Social Justice Humanitas Academy in Los Angeles. In addition to providing a range of supports and services, the school has built-in time for planning and collaboration and for teachers and students to get feedback on their work—all critical practices to support deeper learning. It’s important to acknowledge, though, that just because a school provides services, it doesn’t mean poverty goes away. Schools can’t fight poverty by themselves. They can only mitigate some of the effects of poverty to support student learning.

What are the key policy levers for advancing deeper learning?

Policies that focus on making sure the conditions for learning are in place—equity in resources, course access, and supports—are critical. We also need to make sure our teachers are prepared and supported, which includes providing professional development and capacity-building support so they have clear guidance on how to support their students. Teacher shortages, which exist throughout the country, undermine efforts to advance deeper learning because we resort to filling classrooms with inexperienced teachers who often haven’t been fully prepared. We need smart policies, higher salaries, and other incentives, like housing support, to recruit and retain highly skilled teachers in these schools.